Black War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Black War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Australian frontier wars | |||||||

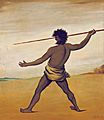

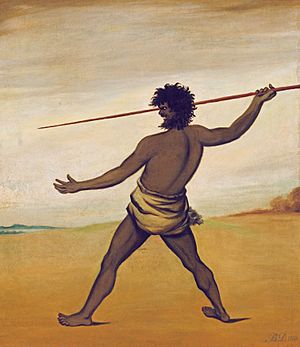

An 1838 painting by Benjamin Duterrau of a Tasmanian Aboriginal throwing a spear |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| British Empire | Aboriginal Tasmanians | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Dead: 219 Wounded: 218 Total: 437 |

600–900 dead | ||||||

The Black War was a time of serious fighting between British settlers and Aboriginal Tasmanians in Tasmania. This conflict happened from the mid-1820s until 1832. Both sides fought using a style called guerrilla warfare, which means small groups used surprise attacks and quick raids.

During this war, between 600 and 900 Aboriginal people died, and more than 200 European settlers also lost their lives. Because so many Aboriginal people died, and there were many mass killings, historians still discuss if the Black War should be called an act of genocide.

Contents

What Caused the Conflict?

The names "Black War" and "Black Line" were first used by a journalist named Henry Melville in 1835. However, historian Lyndall Ryan thinks it should be called the Tasmanian War. She also believes there should be a public memorial for everyone who died on both sides.

The fighting got much worse in the late 1820s. This led Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur to declare martial law. This rule basically meant that killing Aboriginal people was allowed without punishment. In November 1830, he ordered a huge military operation called the Black Line. About 2,200 regular people and soldiers formed a long moving line. They tried to push Aboriginal people out of the settled areas and onto the Tasman Peninsula in the southeast. The idea was to keep them there permanently.

The Black War started because British settlers and their farm animals quickly spread across Tasmania. These areas had been traditional hunting grounds for Aboriginal people. Historian Nicholas Clements says the Aboriginal violence was a way of resisting an invading enemy. He explains that Aboriginal attacks were often for revenge. This was because convicts, settlers, and soldiers often kidnapped and harmed Aboriginal women and girls. Also, from the late 1820s, Aboriginal people were very hungry. Their hunting grounds were shrinking, and native animals were disappearing. This made them raid settlers' homes for food.

On the other hand, European settlers were very scared of Aboriginal attacks. They believed that getting rid of the Aboriginal population was the only way to have peace. Clements noted that as Aboriginal violence increased, so did revenge attacks and surprise attacks by settlers.

Aboriginal groups usually attacked during the day. They used spears, rocks, and waddies (wooden clubs) to harm settlers, shepherds, and their animals. They also often set fire to homes, haystacks, and crops. European attacks were usually at night or early morning. Groups of civilians or soldiers would surprise Aboriginal camps while people were sleeping.

From 1830, Governor Arthur offered rewards for capturing Aboriginal people. However, rewards were also paid when Aboriginal people were killed. Starting in 1829, efforts were made with the help of George Augustus Robinson to start a "friendly mission." The goal was to convince Aboriginal people to give up and move to a safe island. From November 1830 to December 1831, some groups accepted this offer. About 46 people were first sent to Flinders Island, where it was believed they could not escape.

Even though the fighting mostly stopped by January 1832, another 148 Aboriginal people were captured in the island's northwest over the next four years. They were then forced to move to Hunter Island and then Flinders Island.

Early Days of Conflict

European seal hunters started working in Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania's old name) in late 1798. But the first big European presence came five years later. In September 1803, a small military base was set up at Risdon, near present-day Hobart. Over the next five months, there were several violent meetings with local Aboriginal groups. Shots were fired, and an Aboriginal boy was taken.

David Collins arrived as the colony's first governor in February 1804. He had orders from London to punish any Europeans who harmed Aboriginal people. However, he did not make these orders public. This meant there were no clear rules on how to handle violent conflicts.

On May 3, 1804, soldiers from Risdon fired grapeshot (small metal balls) from a carronade (a type of cannon) at about 100 Aboriginal people. This happened after an encounter at a farm. Settlers and convicts also fired rifles, pistols, and muskets. A magistrate named Robert Knopwood later said that five or six Aboriginal people were killed. But other witnesses claimed as many as 50 people died in what became known as the Risdon massacre.

A lot of violence broke out during a drought in 1806–7. Aboriginal groups in both the north and south of the island killed or wounded several Europeans. This was caused by fighting over hunting areas. Explorer John Oxley wrote in 1810 about the "many terrible cruelties" done to Aboriginal people by convict bushrangers in the north. This then led to Aboriginal attacks on lonely white hunters.

Between 1807 and 1813, about 600 new settlers arrived from Norfolk Island. This increased tensions as they set up farms along the Derwent River and near Launceston. They took over 10 percent of Van Diemen's Land. By 1814, over 12,700 hectares of land were being farmed. There were also 5,000 cattle and 38,000 sheep. The Norfolk Islanders used violence to claim land, attacking Aboriginal camps at night. These attacks led to Aboriginal groups raiding settlers' cattle in the southeast.

Between 1817 and 1824, the number of settlers grew from 2,000 to 12,600. In 1823 alone, over 1,000 land grants were given to new settlers. These grants covered 175,704 hectares. By that year, Tasmania's sheep population reached 200,000. The "Settled Districts" covered 30 percent of the island's land. This fast settlement turned traditional kangaroo hunting grounds into farms with animals, fences, and walls. Police and military patrols also increased to control convict farm workers.

Over the first 20 years of settlement, Aboriginal people launched at least 57 attacks on white settlers. By 1820, the violence was happening much more often. One Russian explorer reported that year that "the natives of Tasmania live in a state of constant hostility against the Europeans." From the mid-1820s, the number of attacks by both white and Black people rose sharply.

The Crisis Years: 1825–1831

From 1825 to 1828, the number of Aboriginal attacks more than doubled each year. This caused great fear among settlers. By 1828, historian Clements says, settlers knew they were in a war. But it was not a normal war. The Aboriginal people were not one single group but many different tribes. They had no fixed homes or clear leaders.

George Arthur, who became Governor of the colony in May 1824, had announced that Aboriginal people were protected by British law. He threatened to punish Europeans who continued to "wantonly destroy" them. Arthur wanted to create a "native institution" for Aboriginal people. In September 1826, he hoped that the trial and hanging of two Aboriginal people, arrested for spearing three settlers, would stop further violence. But between September and November 1826, six more settlers were killed. The Colonial Times newspaper then demanded a big change in policy. It urged that all Aboriginal people be forced to move from the Settled Districts to an island in the Bass Strait. The newspaper warned: "Self-defence is the first law of nature. The government must remove the natives—if not, they will be hunted down like wild beasts, and destroyed!"

To calm the rising fear, Arthur issued a government notice on November 29, 1826. It explained when settlers could legally kill Aboriginal people if they attacked settlers or their property. The notice said that attacks could be fought back "in the same way as if they had come from an official State." The Colonial Times saw this notice as a declaration of war on Aboriginal people in the Settled Districts. Some settlers thought it was a "noble service to shoot them down." However, Clements believes the legality of killing Aboriginal people was never clear to settlers. Historian Lyndall Ryan argues that Arthur only wanted to force them to surrender.

Over the summer of 1826–7, groups from the Big River, Oyster Bay, and North Midlands nations speared several stock-keepers on farms. They made it clear they wanted the settlers, their sheep, and cattle to leave their kangaroo hunting grounds. Settlers fought back strongly, leading to many mass killings. On December 8, 1826, a group led by Kickerterpoller threatened a farm overseer. The next day, soldiers from the 40th Regiment killed 14 Aboriginal people and captured nine others, including Kickerterpoller. In April 1827, two shepherds were killed. A group of settlers and soldiers then launched a surprise attack at dawn on an undefended Aboriginal camp, killing as many as 70 Aboriginal people. In March and April, several settlers and convict servants were killed. A pursuit group got revenge in a dawn raid where they "fired volley after volley in among the Blackfellows... they reported killing some two score (40)." In May 1827, a group of Oyster Bay Aboriginal people killed a stock-keeper. A party of soldiers, police, settlers, and stock-keepers then raided the camp at night.

Over 18 days in June 1827, at least 100 members of the Pallittorre group were killed. This was in revenge for the killing of three stockmen. Ryan estimates that from December 1, 1826, to July 31, 1827, over 200 Aboriginal people were killed in the Settled Districts. This was in revenge for 15 settlers being killed. An entire group of 150 Oyster Bay people may have been killed in one chase in November 1827, greatly reducing their numbers. In September, Arthur appointed 26 more police and sent 55 more soldiers into the Settled Districts to deal with the rising conflict. Between September 1827 and the following March, at least 70 Aboriginal attacks were reported, killing 20 settlers. By March 1828, the death toll in the Settled Districts had risen to 43 settlers and probably 350 Aboriginal people. But by then, reports showed that Aboriginal people were more interested in raiding huts for food like bread, flour, tea, and digging up potatoes, rather than killing settlers.

Arthur told the Colonial Office in London that Aboriginal people "already complained that the white people have taken possession of their country, encroached upon their hunting grounds, and destroyed their natural food, the kangaroo." He suggested moving Aboriginal people to "some remote quarter of the island, which should be reserved strictly for them." He also suggested giving them food and clothing, and protecting them, "on condition of their confining themselves peaceably to certain limits." He said Tasmania's northeast coast was the best place for such a reserve. He suggested they stay there "until their habits shall become more civilised." He then issued a "Proclamation Separating the Aborigines from the White Inhabitants" on April 19, 1828. This divided the island into two parts to control contact between white and Black people. The northeast region was a place many Aboriginal groups visited for its rich food and mild climate. It was also mostly empty of settlers. But this proclamation also officially allowed the use of force to remove any Aboriginal people from the Settled Districts. Historian James Boyce noted: "Any Aborigine could now be legally killed for doing no more than crossing an unmarked border that the government did not even bother to define."

In a letter to London officials in April 1828, Arthur admitted:

"We are undoubtedly the first aggressors, and the desperate characters amongst the prisoner population, who have from time to time absconded into the woods, have no doubt committed the greatest outrages upon the natives, and these ignorant beings, incapable of discrimination, are now filled with enmity and revenge against the whole body of white inhabitants. It is perhaps at this time in vain to trace the cause of the evil which exists; my duty is plainly to remove its effects; and there does not appear any practicable method of accomplishing this measure, short of entirely prohibiting the Aborigines from entering the settled districts ..."

Arthur enforced the border by sending almost 300 soldiers from the 40th and 57th Regiments to 14 military posts. This seemed to stop Aboriginal attacks. Through the winter of 1828, few Aboriginal people appeared in the Settled Districts. Those who did were driven back by military groups. Among them were at least 16 undefended Oyster Bay people who were killed in July by soldiers.

Martial Law, November 1828

Any hopes for peace in the Settled Districts ended in spring. Between August 22 and October 29, 15 settlers died in 39 Aboriginal attacks. This was about one attack every two days. The Oyster Bay and Big River groups raided stock huts. The Ben Lomond and North groups burned down huts along the Nile and Meander rivers. From early October, Oyster Bay warriors also began killing white women and children.

Because the violence got worse, Arthur called a meeting of Tasmania's Executive Council. On November 1, he declared martial law against the Aboriginal people in the Settled Districts. They were now considered "open enemies of the King." Declaring martial law meant the government could use force "against rebels and enemies" to kill in war for self-defense. Arthur's move was basically a declaration of total war. Soldiers could now arrest or shoot any Aboriginal person in the Settled Districts who resisted them. However, the proclamation also ordered settlers:

" ... that the actual use of arms be in no case resorted to, if the Natives can by other means be induced or compelled to retire into the places and portions of this Island herein before excepted from the operation of Martial Law; that bloodshed be checked, as much as possible; that any Tribes which may surrender themselves up, shall be treated with every degree of humanity; and that defenceless women and children be invariably spared."

Martial law stayed in place for over three years. This was the longest period of martial law in Australian history.

About 500 Aboriginal people from five groups were still in the Settled Districts when martial law was declared. Arthur's first step was to encourage groups of civilians to start capturing them. On November 7, a group captured Umarrah, who was thought to have led a deadly attack in February 1827. They also captured four others, including his wife and a child. Umarrah remained defiant and was jailed for a year. Arthur then set up military patrols of eight to 10 men from the 39th, 40th, and 63rd Regiments. These groups were ordered to stay in the field for about two weeks, searching the Settled Districts for Aboriginal people to capture or shoot. By March 1829, 23 military groups, about 200 armed soldiers, were searching the Settled Districts. They were mainly trying to kill, not just capture, Aboriginal people. Aboriginal people were killed in groups of up to 10 at a time, mostly in dawn raids on their camps. By March, news reports said about 60 Aboriginal people had been killed since martial law began, with 15 settlers lost.

Aboriginal attacks made settlers angry and wanting revenge. But Clements says the main feeling settlers had was fear, from constant worry to extreme terror. He noted: "Everybody on the frontier was afraid, all the time." The financial loss from theft, animal destruction, and fires was a constant threat. There were no insurance companies, so settlers could lose everything if crops and buildings were burned or animals killed. The Hobart Town Courier newspaper warned that Aboriginal people had declared a "war of extermination" on white settlers. The Colonial Times declared: "The Government must remove the natives. If not they will be hunted down like wild beasts and destroyed."

By winter 1829, the southern part of the Settled Districts was a war zone. Aboriginal people later remembered campsites where their relatives had been killed. Several more incidents were reported where Aboriginal people raided huts for food and blankets or dug up potatoes, but they were also killed. To try and make peace with Aboriginal people, Arthur arranged for "proclamation boards" to be given out. These boards had four pictures showing white and Black Tasmanians living peacefully together. They also showed the legal results for anyone, white or Black, who committed violence. An Aboriginal person would be executed for killing a white settler, and a settler would be executed for killing an Aboriginal person. However, no settler was ever charged or tried in Tasmania for harming or killing an Aboriginal person.

Aboriginal people continued their attacks on settlers, killing 19 settlers between August and December 1829. The total for that year was 33, six more than in 1828. But the white response was even stronger. One report after an expedition noted "a terrible slaughter" from an overnight raid on a camp. In late February 1830, Arthur offered a reward for every captured Aboriginal person. He also tried to get more soldiers, asking for reinforcements from other regiments. In April, he also told London that sending more convicts to remote frontier areas would help protect settlers. He specifically asked that all convict ships be sent to Van Diemen's Land.

Aborigines Committee

In March 1830, Arthur appointed Anglican Archdeacon William Broughton to lead a six-person Aborigines Committee. Their job was to investigate why Aboriginal people were hostile and suggest ways to stop the violence. Sixteen months had passed since martial law was declared in November 1828. In that time, there had been 120 Aboriginal attacks on settlers, resulting in about 50 deaths and over 60 wounded. During the same period, at least 200 Aboriginal people had been killed. Settlers and soldiers gave evidence of killings and terrible acts on both sides. But the committee was also told that despite the attacks, some settlers believed very few Aboriginal people were left in the Settled Districts. The inquiry happened while fighting was getting even worse. In February alone, there were 30 separate incidents where seven Europeans were killed.

In its report, published in March 1830, the committee noted that "It is clear that (the Aboriginal people) have lost the sense of superiority of white men, and the dread of the effects of fire-arms." They were now systematically attacking settlers and their property. The committee's report supported the reward system. It also suggested more mounted police patrols and urged settlers to stay armed and alert. Arthur sent their report to Secretary of State for War and the Colonies Sir George Murray. He pointed out that "lawless convicts" had acted very cruelly towards Aboriginal people. But he also said, "it is increasingly apparent the Aboriginal natives of this colony are, and have ever been, a most treacherous race." He claimed that the kindness they received from free settlers had not made them more civilized. Murray replied in a letter that it was possible the entire "race" of Tasmanian Aborigines would soon disappear. He warned that any actions leading to their extinction would badly stain the British government's reputation.

News of friendly meetings with Aboriginal people and a seasonal drop in attacks made Arthur issue a government notice on August 19. He expressed his satisfaction that the Aboriginal people were showing "a less hostile disposition." He advised settlers to carefully "abstain from acts of aggression against these benighted beings" and let them feed and leave. But the attacks continued. As public fear and anger grew, the Executive Council met a week later. They decided a full-scale military operation was needed to end what threatened to become a "war of extermination" between settlers and the Big River and Oyster Bay people.

Martial law was extended to all of Van Diemen's Land on October 1. Arthur ordered every able-bodied male settler to gather on October 7. They were to join a huge effort to sweep "these miserable people" from the region. This campaign became known as the Black Line. The settler press welcomed it with excitement. The Hobart Town Courier said it doubted settlers would need convincing "to accomplish the one grand and glorious object now before them."

North-west Conflict

Violence in the island's north-west, where the settlers worked for the Van Diemen's Land Company, started in 1825. It was caused by arguments over Aboriginal women, who were often harmed or taken, and the destruction of kangaroo populations. A cycle of increasing violence began in 1827 after white shepherds tried to force themselves on Black women. A shepherd was attacked, and over 100 sheep were killed in revenge. In turn, a white group launched a dawn attack on an Aboriginal campsite, killing 12. This conflict led to the Cape Grim massacre on February 10, 1828. In this event, shepherds with muskets ambushed up to 30 Aboriginal people as they gathered shellfish at the bottom of a cliff.

The number of North West Aboriginal groups fell from 700 to 300 during the 1820s. In the North nation, where shepherds promised to shoot Aboriginal people whenever they saw them, numbers dropped from 400 in 1826 to fewer than 60 by mid-1830. Violence stopped in 1834 but started again between September 1839 and February 1842. During this time, Aboriginal people made at least 18 attacks on company men and property.

The Black Line: October–November 1830

The Black Line was made up of 2,200 men. This included about 550 soldiers (a little over half of all soldiers in Van Diemen's Land), 738 convict servants, and 912 free settlers or civilians. Arthur was in charge overall, but Major Sholto Douglas led the forces. The men were divided into three groups and helped by Aboriginal guides. They formed a long line, over 300 km long. They started moving south and east across the Settled Districts on October 7. The plan was to trap members of four of the nine Aboriginal nations in front of the line. They wanted to push them across the Forestier Peninsula to East Bay Neck and into the Tasman Peninsula. Arthur had set this area aside as an Aboriginal Reserve.

The campaign faced bad weather, rough land, thick bush, and huge swamps. Maps were not good, and supplies were hard to get. Even though two of the groups met in mid-October, the difficult land soon broke the line, leaving many wide gaps. Aboriginal people were able to slip through these gaps. Many of the men, who were by then barefoot and their clothes torn, left the line and went home. The only success of the campaign was a surprise attack at dawn on October 25, where two Aboriginal people were captured and two were killed. The Black Line was ended on November 26.

Ryan estimates that barely 300 Aboriginal people were still alive on the entire island. About 200 of them were in the area where the Black Line was operating. Yet, they launched at least 50 attacks on settlers during the campaign, both in front of and behind the line. They often raided huts for food.

Surrender and Removal

Settlers hoped for peace in the summer of 1830-31. Aboriginal attacks dropped to a low level. The Colonial Times newspaper thought their enemy had either been wiped out or were too scared to act. But the north remained a dangerous place. Even though the number of attacks in 1831 was less than a third of the previous year (70 compared to 250 in 1830), settlers were still so scared that many men refused to go to work.

However, as the Aborigines Committee found in new hearings, there was some good news from the work of George Augustus Robinson. He was a humanitarian who, in 1829, was put in charge of a supply depot for Aboriginal people on Bruny Island. From January 1830, Robinson went on several trips across the island to meet Aboriginal people. In November, he got 13 of them to surrender. This made him write to Arthur, claiming he could remove "the entire black population," which he thought was 700. In a new report on February 4, 1831, the Aborigines Committee praised Robinson's "conciliatory mission." They also praised his efforts to learn local languages and "explain the kind and peaceful intentions of the government and the settlers generally towards them." The committee suggested that Aboriginal people who surrendered should be sent to Gun Carriage Island in Bass Strait. But the committee also urged settlers to stay alert. They recommended that groups of armed men be placed in the most remote stock huts. In response, up to 150 stock huts were turned into ambush spots. Military posts were set up on native travel routes, and new barracks were built.

Arthur's peaceful approach and his support for Robinson's "friendly mission" were widely criticized by settlers and the settler press. This criticism grew stronger after a series of violent raids in mid-winter. These raids were launched by hungry, cold, and desperate Aboriginal people in the Great Western Tiers. These raids ended with the murder of Captain Bartholomew Thomas and his overseer James Parker on August 31, 1831. These killings turned out to be the last of the Black War. But they caused a huge wave of fear and anger. This was especially true because Thomas had been kind to Aboriginal people and tried to make peace with them. The Launceston Advertiser declared that the only option left was the "utter annihilation" of the Aboriginal population. Another newspaper feared that the natives would do even worse things in the coming season. Several weeks later, a group robbed huts at Great Swansea, causing panic. In late October, 100 armed settlers formed a line across the narrow part of Freycinet Peninsula. They tried to capture several dozen Aboriginal people who had gone onto the peninsula. The line was given up four days later after Aboriginal people slipped through and escaped at night.

On December 31, 1831, Robinson and his group of about 14 Aboriginal helpers negotiated the surrender of 28 members of the Mairremmener people. This group was a mix of Oyster Bay and Big River tribes. This small group of 16 men, nine women, and one child, led by Tongerlongeter and Montpelliatta, was all that was left of what had once been one of the island's most powerful groups. Much of Hobart Town's population lined the streets as Robinson walked with them through the main street towards Government House. They were sent to the Wybalenna settlement on Flinders Island. They joined another 40 Aboriginal people who had been captured earlier, although 20 others on the island had already died. By late May, many more, including Kickerterpoller and Umarrah, had also gotten influenza and died.

The surrender in December mostly ended the Black War. There were no more reports of violence in the Settled Districts from that date. However, isolated acts of violence continued in the north-west until 1842.

Martial law was removed in January 1832, two weeks after the well-known surrender. The reward for captured Aboriginal people was also stopped on May 28, 1832.

In February 1832, Robinson started several trips to the west, north-west, and Launceston area. He wanted to get the remaining Aboriginal people to surrender. He believed this plan was "for their own good" and would save them from being killed by settlers. He also thought it would give them the benefits of British civilization and Christianity. He warned them that they would face violence without protection. He convinced several small groups to be sent to Flinders Island. Many died there from pneumonia, influenza, and catarrh. But from early 1833, he started using force to capture those who still lived freely in the north-east, even though the violence had stopped. Both Hunter Island and penal stations (prisons) on islands in Macquarie Harbour were used to hold captured Aboriginal people. Many quickly died from disease there, and the death rate reached 75 percent. Robinson noted about conditions in the Macquarie Harbour penal stations: "The mortality was dreadful, its ravages was unprecedented, it was a dreadful calamity." In November 1833, all surviving Aboriginal people were moved from Macquarie Harbour to Flinders Island.

By early 1835, almost 300 people had surrendered to Robinson. He reported to the colonial secretary: "The entire Aboriginal population is now removed." However, in 1842, he found one remaining family near Cradle Mountain, who then surrendered. Men on the island were expected to clear forest land, build roads, put up fences, and shear sheep. Women were required to wash clothes, attend sewing classes, and attend other classes. Everyone was expected to wear European clothes, and many women were given European names. A high rate of infectious disease at the Wybalenna settlement on Flinders Island cut the population from about 220 in 1833 to 46 in 1847.

How Many Died?

Estimates of Tasmania's Aboriginal population in 1803, when the British first arrived, range from 3,000 to 7,000. Lyndall Ryan's studies led her to believe there were about 7,000 people across the island's nine nations. However, Nicholas Clements, using research by N.J.B Plomley and Rhys Jones, suggests a figure of 3,000 to 4,000.

| Phase | Aboriginal People killed (est.) |

Colonists killed |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nov 1823—Nov 1826 | 80 | 40 | 120 |

| Dec 1826—Oct 1828 | 408 | 61 | 469 |

| Nov 1828—Jan 1832 (martial law) |

350 | 90 | 440 |

| Feb 1832—Aug 1834 | 40 | 10 | 50 |

| Total | 878 | 201 | 1079 |

But Aboriginal numbers started dropping almost right away. Violent encounters were reported in the Hobart region. In the north, Lieutenant-Governor William Paterson is thought to have ordered soldiers to shoot Aboriginal people wherever they were found. This led to the almost complete disappearance of North Midlands groups after 1806. In 1809, surveyor-general John Oxley reported that kangaroo hunting by white people had caused "a considerable loss of life among the natives" across the colony. One settler, the convict adventurer Jørgen Jørgensen, also claimed that Aboriginal numbers were "much reduced during the first six or seven years of the colony" as white people "harassed them without punishment." By 1819, the Aboriginal and British populations were about equal, with about 5,000 of each. However, among the settlers, men outnumbered women four to one. At that time, both groups were generally healthy, with infectious diseases not becoming widespread until the late 1820s.

Ryan accepts a figure of 1,200 Aboriginal people living in the Settled Districts in 1826, at the start of the Black War. Clements believes the number in eastern Tasmania was about 1,000.

Historians have different ideas about the total number of deaths in the Black War. They agree that most killings of Aboriginal people were not reported. The Colonial Advocate newspaper reported in 1828 that "up country, instances occur where the Natives are 'shot like so many crows', which never come before the public'." The table above, showing deaths among Aboriginal people and settlers, is based on numbers from Ryan's account of the conflict.

About 100 Tasmanian Aboriginal people survived the conflict. Clements, who believes the Aboriginal population was about 1,000 at the start of the Black War, has concluded that 900 died during that time. He thinks about one-third may have died from fighting among themselves, disease, and natural causes. This leaves a "careful and realistic" estimate of 600 who died in frontier violence. However, he admits: "The true figure might be as low as 400 or as high as 1,000."

Historical Debate

The Black War has been a very debated topic among historians. It's even been called part of Australia's history wars. Geoffrey Blainey wrote that in Tasmania by 1830: "Disease had killed most of them but warfare and private violence had also been devastating." Keith Windschuttle, in his 2002 book, The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Volume One: Van Diemen's Land 1803–1847, questioned the historical evidence used to figure out how many Aboriginal people were killed and how much conflict there was. He believed it had been exaggerated. He challenged what is called the "Black armband view of history" of Tasmanian settlement. Windschuttle argued that there were only 2,000 Aboriginal people in Tasmania when the British arrived. He also claimed they had a troubled society with no clear tribal organization or connection to the land. He said they were not able to fight a guerrilla war with the settlers. He argued they were more like "black bushrangers" who attacked settlers' huts for loot. He believed they were led by "educated black terrorists" who were unhappy with white society. He concluded that two settlers had been killed for every Aboriginal person, and there was only one massacre of Aboriginal people.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Guerra negra para niños

In Spanish: Guerra negra para niños

- List of massacres of Indigenous Australians

- Trugernanner & Fanny Cochrane Smith

- Manganinnie, an Australian 1980 film

- The Nightingale, an Australian 2018 film

- Tunnerminnerwait

- Australian frontier wars

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |