Cape Grim massacre facts for kids

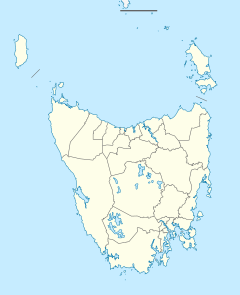

The Cape Grim massacre was a terrible event that happened on 10 February 1828. A group of Aboriginal Tasmanians were gathering food on a beach in north-west Tasmania. They were attacked by four workers from the Van Diemen's Land Company (VDLC).

About 30 Aboriginal men are believed to have been killed. This attack was in revenge for an earlier raid by Aboriginal people on the company's sheep. It was part of a growing conflict called the "Black War". This war was a period of fighting between British colonists and Aboriginal Australians in Tasmania. It lasted from the mid-1820s to 1832.

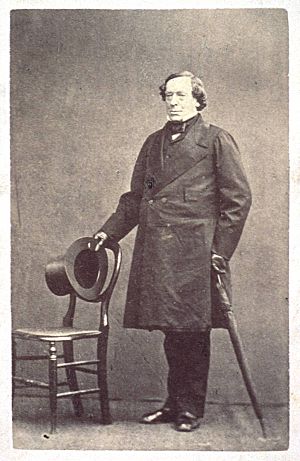

News of the killings at Cape Grim did not reach Governor George Arthur for almost two years. Governor Arthur sent George Augustus Robinson to investigate. Robinson was a government worker who tried to make peace with Aboriginal people. Later, statements from company workers, a ship captain's wife, and an Aboriginal woman gave more information.

However, the details of what happened are still unclear. Some historians, like Keith Windschuttle, have questioned how many people died. Some even doubt if the massacre happened at all. The place where the massacre happened is now called Taneneryouer. It faces some small islands known as The Doughboys.

Contents

Background to the Conflict

Clans of the North West Aboriginal nation had faced violence from European settlers since 1810. This began when seal hunters took Aboriginal women away. In 1820, a group of sealers attacked Pennemukeer women near Cape Grim/Kennaook. The women were collecting birds and shellfish. The sealers captured them and took them to Kangaroo Island. In response, Pennemukeer men attacked the sealers, killing three of them.

Arrival of the Van Diemen's Land Company

More conflict started when the VDLC arrived in late 1826. This company was formed in London in 1824. Its goal was to raise many Merino and Saxon sheep. England needed a lot of wool at that time. The company was given a large area of land in the northwest of Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania). This land was about 100 thousand hectares (250 thousand acres).

About 400 to 500 Aboriginal people lived in this area. They had kept the grassy plains clear of trees for generations. They did this by using "fire-stick farming" (controlled burning). Soon, ships arrived with animals and workers. Most workers were "indentured servants" or convicts. They worked as shepherds and farmers. They set up sheep stations at Cape Grim/Kennaook and Circular Head. These stations took over important Aboriginal kangaroo hunting grounds.

Edward Curr's Role

Edward Curr was the VDLC's Chief Agent. He reported to directors in London. But in this remote area, he also acted like a magistrate (a judge). Curr quickly became known as a strict and unfair leader. Within a year, his workers were known for treating local Aboriginal people very badly. Curr sometimes even encouraged this violence.

Rosalie Hare was the wife of a ship's captain. She arrived in January 1828 and stayed with Curr's family. She wrote in her journal about how often Aboriginal people attacked shepherds. But she also noted that Europeans took revenge. She wrote that her countrymen thought killing Aboriginal people was an honor. She said they wanted to get rid of them completely.

The Massacre at Cape Grim

The main reason for the February killings was an event in December 1827. The Peerapper clan from West Point was visiting the area. They were looking for bird eggs and seals. Convicts working for the VDLC were looking after sheep. They managed to take some Peerapper women away. When the Peerapper men became upset, a fight started. One shepherd, Thomas John, was speared in the leg. Several Peerapper men, including a chief, were shot and killed.

John was taken back to Circular Head. Curr told the VDLC directors about the injury. He said his shepherd was speared in a long fight. He claimed a "very strong party of Natives" had attacked the men.

Revenge Attack

A group of Peerapper, likely led by Wymurrick, returned to Cape Grim/Kennaook on 31 December. This was a month after the first fight. They wanted revenge. They destroyed 118 sheep belonging to the company. The company ship Fanny was then sent to Cape Grim/Kennaook. Its captain, Richard Frederick, was supposed to collect sheep.

While there, Frederick helped the shepherds search for the Peerapper clan. He knew the area and the Aboriginal people well. They found the Peerapper camp. According to Rosalie Hare's journal, they killed 12 men in a surprise night attack.

Several days later, on 10 February, the same four shepherds are believed to have attacked another group. This was about six weeks after the sheep were destroyed. They trapped Aboriginal men, women, and children at Taneneryouer. The Aboriginal people were eating mutton-birds they had caught near the Doughboy Islands.

There is no single clear story of what happened next. It is thought that the Aboriginal people panicked when they saw the armed Europeans. They ran in different directions. One group, believed to be all men, was killed near a 60-metre (200 ft) cliff. Two people, one of the convicts and an Aboriginal woman, said 30 people died. Other estimates vary.

The Investigation

On 14 January, Curr sent a report to the VDLC directors. He described the Fanny's trip and the night attack on the Peerapper camp. Curr said there were about 70 Peerapper people. He claimed the shepherds waited until dawn before leaving without firing a shot. He said their muskets would not work because of heavy rain.

Historian Ian McFarlane says Curr's story is unlikely. He believes Rosalie Hare's account is more believable. McFarlane said the men would have known the Peerapper were afraid to move at night. It was unlikely they would wait all night in the cold and rain. They would have lost their advantage by waiting for daylight.

Curr's Reports and Goldie's Letter

Two weeks later, on 28 February, Curr briefly mentioned the events of 10 February. He told the directors that shepherds had met a "strong party of natives." He said after a long fight, six Aboriginal people were left "dead on the field." This included their chief. He added that this would scare them and make them stay away.

Curr did not report anything else about the incident. The directors wrote back, saying they were "regretful" about the deaths. They also pointed out that it was unclear who started the fight. Curr, as a magistrate, did not investigate further. He also did not tell Governor Arthur about the deaths.

The massacre might have remained a secret if not for Alexander Goldie. He was an agricultural superintendent for the VDLC. He was unhappy with the company. In November 1829, he wrote a long letter to Governor Arthur. In it, he confessed to being involved in killing Aboriginal people. He also revealed:

Many Aboriginal people have been shot by the Company's Servants. There were several fights while their animals were in that area. Once, many were shot (I never heard the exact number). Mr Curr knew about it, but he never did anything, even though he was a magistrate. At that time, there was no law against the Aboriginal people, nor were they bothering the Company's animals when they were attacked...

Goldie also wrote a strong 110-page letter to the VDLC directors. He said Curr had personally encouraged the killing of other Aboriginal people.

Robinson's Investigation

Governor Arthur asked Robinson to investigate Goldie's claims. Robinson was on his "friendly mission" to Aboriginal Tasmanians in the north-west. It took until June of the next year for Robinson to arrive. On 16 June, he spoke with Charles Chamberlain. Chamberlain was one of the four convict shepherds involved.

Four days later, Robinson questioned a group of Aboriginal women. They were at a sealer's camp near Robbins Passage. Some of them told him about Thomas John being speared. They also spoke about an Aboriginal chief being shot. They said tribe members later returned to push sheep off a cliff. They also described the massacre of 10 February. They said VDLC shepherds had surprised a whole tribe. This tribe had come for muttonbirds at the Doughboys. They massacred thirty of them.

On 10 August, Robinson met William Gunchannon. He was another of the four men at the massacre. Gunchannon admitted he was there. He said it happened about six weeks after the sheep were destroyed. But he did not want to give many details. He told Robinson that the group attacked on 10 February included men and women. But he said he did not know if anyone was killed. Robinson later wrote that Gunchannon "seemed to glory in the act." He said he would shoot them whenever he met them. Robinson did not interview the other two men. Richard Nicholson had drowned. John Weavis had moved to Hobart.

Bushman Alexander McKay guided Robinson. Robinson visited Cape Grim/Kennaook. He found the place where the massacre happened. At the northern part of Taneneryouer, Robinson saw the steep cliff. This was where the Aboriginal people had driven the sheep. South of the cliff was a steep path to the beach. The Aboriginal women had said this was where the massacre happened.

Curr's Later Explanations

The VDLC directors asked Curr to respond to Goldie's complaints. Curr's reply, on 7 October 1830, gave a more detailed report. But it was very different from Robinson's accounts. Curr told the directors that a "very large" Aboriginal group had gathered on a hill. This hill overlooked the shepherds' hut. He wrote:

Our men saw them there. They told me they thought the Aboriginal people were coming to attack them again. So, they went out to meet them. In the fight that followed, they killed six Aboriginal people. This is how the story was first told to me. Nothing was said about the Aboriginal people returning from the Islands with birds and fish. I do not believe that was the case now, but I think it is likely they were going there.

...I have no doubt that our men truly believed the Aboriginal people were there only to surround and attack them. With that idea, it would be crazy for them to wait. I thought about these things at the time. I had thought of investigating the case. But first, I saw there was a strong chance our men were right. Second, if they were wrong, it was impossible to prove it. And third, just asking questions would make every man leave Cape Grim.

Seven months later, in May 1831, Governor Arthur met Curr. Arthur showed Curr Robinson's report. He told Curr to say if the findings were wrong. Curr wrote to the Governor, saying: "I believe it to be untrue. I have no doubt that some Aboriginal people were killed. I think the real number was three... as the men told me, they had no choice but to act as they did."

Different Views on the Events

The different stories about 10 February 1828 have led some historians to visit the site. They try to guess what most likely happened. Their ideas are very different.

Historian Keith Windschuttle visited Cape Grim/Kennaook. He disagreed with much of Robinson's description. He said the shepherds could not have surprised the Aboriginal people on the beach. He explained that the slope above the beach is too steep to climb down. Shepherds would have had to use a track around the bay. This would have given the Aboriginal people at least five minutes to escape. They could have swum away or gone around the rocks.

Windschuttle also found problems with Robinson's description of Aboriginal people hiding in a rock. He said it would be hard for shepherds to force captives up the track while carrying weapons. Once at the top, it would be impossible to stop them from escaping over the open land. He said if they wanted to kill everyone, they would have done it on the beach. Windschuttle said the difficult land and old muskets made it hard to believe four shepherds killed 30 people. He thought Curr's story was more believable. In Curr's story, the shepherds felt threatened and attacked first. Windschuttle also accepted Curr's claim of only six deaths. He believed the fight happened on the open grassland near Victory Hill.

However, Ian McFarlane's study of the area found problems with Windschuttle's ideas. McFarlane said maps showed the shepherds' hut was about 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) northeast of Victory Hill. This was too far for spears thrown by Aboriginal people on the hill. McFarlane argued that leaving the safety of a hut to fight a larger group of Aboriginal people on higher ground would be "gross stupidity." Especially since one convict, John Weavis, was a former soldier. McFarlane said a musket fired uphill would not be as good as spears. Spears could be thrown accurately up to 90 metres (300 ft). He wrote that a large number of Aboriginal people with spears on high ground would have won. He found it hard to believe four shepherds would be unharmed. McFarlane noted that Chamberlain, Gunchannon, and the Aboriginal woman did not mention the hut or the hill. Their stories focused only on Taneneryouer. He concluded that Curr's story was "clearly implausible." He believed Curr changed the location to make the Aboriginal people seem like the attackers.

McFarlane suggested that Chamberlain's and the Aboriginal women's stories were two parts of the same event.

Aftermath

According to McFarlane, most Aboriginal people in Tasmania's north-west were hunted down and killed. This was done by VDLC hunting groups, under Curr's control. He says between 400 and 500 Aboriginal people lived in the region before the company arrived. By 1835, their number had dropped to just over 100.

From 1830, Robinson began gathering the last Aboriginal survivors. He wanted to take them to a "place of safety" on an island off Tasmania's north coast. However, those in the north-west avoided him. In 1830, Robinson found six Aboriginal women who had been taken away. He also found an 18-year-old man called "Jack of Cape Grim." His Aboriginal name was Tunnerminnerwait. He was from the Parperloihener group of Robbins Island. Robinson threatened the sealers with legal action if they did not give up the Aboriginal people. He promised the Aboriginal people safety and a return to their tribal lands later.

See also

In Spanish: Masacre de Cape Grim para niños

In Spanish: Masacre de Cape Grim para niños

- History wars

- List of massacres in Australia

- List of massacres of Indigenous Australians

- Tasmanian Aborigines

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |