Coniston massacre facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Location in Northern Territory

|

|

| Date | August 14 – October 18, 1928 |

|---|---|

| Location | Coniston (Northern Territory) |

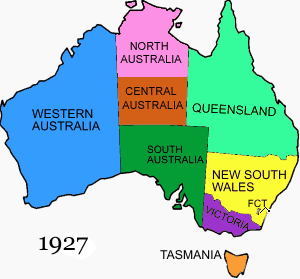

The Coniston massacre was a series of violent events that happened in 1928. It took place near the Coniston cattle station in what is now the Northern Territory of Australia. These events occurred between August 14 and October 18, 1928.

This was the last known officially approved killing of Indigenous Australian people. It was also one of the final events of the Australian Frontier Wars. During these events, police constable William George Murray led groups that killed people from the Warlpiri, Anmatyerre, and Kaytetye groups.

The violence started after a dingo hunter named Frederick Brooks was killed. This happened in August 1928 at a place called Yukurru (also known as Brooks Soak). Official records at the time said 31 people were killed. However, later studies and stories from Aboriginal people suggest that up to 200 people may have died.

Contents

Why the Events Happened

In 1928, Central Australia was a remote area. It was experiencing a very severe drought, which had lasted for four years. This drought played a big part in the events at Coniston.

Water was very important for cattle stations. They needed to control water sources to keep their cattle healthy. As waterholes dried up, Aboriginal people, who were starving, had to move closer to the permanent water sources on the new cattle stations.

Many white settlers believed that the needs of traditional Aboriginal land owners and cattle stations could not both be met. They thought one had to succeed over the other. Ranchers saw Aboriginal people asking for food or hunting cattle as a problem. They would often force Aboriginal people away from these water sources to save their cattle.

The Death of Fred Brooks

Fred Brooks, 61, had worked at Coniston station, about 240 km (150 mi) northwest of Alice Springs. In July 1928, he decided to try hunting dingoes. The station owner, Randall Stafford, warned him it might be dangerous.

On August 2, Brooks left with two 12-year-old Aboriginal boys, Skipper and Dodger. They went to trap dingoes for money. Near a waterhole, he found about 30 Ngalia-Warlpiri people camped. Brooks knew some of them and decided to camp with them. For two days, everything was peaceful, and Brooks caught several dingoes.

Later, a mining explorer warned Brooks that Aboriginal people had been acting "cheeky" and demanding food. Around this time, some Aboriginal children were also being taken away to Alice Springs.

There are different stories about what happened next. One Aboriginal account says that a Warlpiri man, Japanunga Bullfrog, asked Brooks to pay for his wife Marungardi's help with washing. When Brooks did not pay, Japanunga killed him. Another story says Japanunga became jealous and attacked Brooks with a boomerang. This account claims Bullfrog, his uncle Padirrka, and Marungardi beat Brooks to death. Fearing what would happen, Aboriginal elders banished Bullfrog and Padirrka. They told Brooks' boys to say he died naturally.

Finding Brooks' Body

Stories differ about who found Brooks' body first. An Aboriginal man named Alex Wilson later found the body at the deserted waterhole. He rode back to the station to tell what he had found.

The station owner, Randall Stafford, had been in Alice Springs asking police to stop cattle spearing. He returned and heard about Brooks' death. He decided to wait for the police. No one went back to the waterhole to get the body.

On August 11, Constable William George Murray arrived to investigate cattle spearing. When he heard about Brooks' death, he called his boss, J. C. Cawood. Cawood told Murray to handle the Aboriginal people as he thought best.

Murray returned to Coniston and questioned Dodger and Skipper. They named Bullfrog, Padirrka, and Marungali as the killers. Murray then gathered a group, including trackers Paddy and Alex Wilson, Dodger, tracker Major, Randall Stafford, and two white travelers, Jack Saxby and Billie Brisco.

The Violence Begins

Fred Brooks was killed around August 7, 1928. No one ever clearly saw the murder happen. There are different stories about how his body was found and what happened afterward.

On August 15, dingo trapper Bruce Chapman arrived at Coniston. Constable Murray sent Chapman, Paddy, Alex Wilson, and three Aboriginal trackers to the waterhole. They buried Brooks there.

Later that day, two Warlpiri men, Padygar and Woolingar, came to Coniston to trade dingo scalps. Believing they were involved in the murder, Paddy arrested them. Woolingar tried to escape, and Murray shot and wounded him. Woolingar was then chained to a tree for 18 hours.

The next morning, Murray's group, with Padygar and Woolingar chained and walking, went to the Lander River. They found a camp of 23 Warlpiri people. Murray rode into the camp, and shooting started. Three men and a woman, Marungali (Bullfrog's wife), were killed. Another woman died an hour later from her injuries. A search of the camp found items belonging to Brooks.

Randall Stafford was very upset about the shooting and returned to Coniston alone the next morning.

More Shootings

During the night, Murray captured three young boys. Their tribe had sent them to see what the police were doing. Murray had the boys beaten to make them lead the group to other Warlpiri people.

By nightfall, they found four Aboriginal people on a ridge. Paddy and Murray captured two and killed one who tried to run away. After questioning the others and finding they were not involved in Brooks' murder, Murray released them. For the next two days, they found no Aboriginal people. Word had spread, and many had gone into the desert, risking thirst rather than facing the police.

Murray returned to Coniston. He left Padygar and one of the boys, 11-year-old Lolorrbra (Lala), with Stafford. Woolingar had died that night while still chained to the tree. Murray then headed north to continue his search.

Following tracks, the group found a camp of 20 Warlpiri people, mostly women and children. Murray ordered the men to drop their weapons. Not understanding English, the women and children ran, while the men stayed to protect them. The group opened fire, killing three men. Three more died later from their wounds, and many wounded escaped. Murray later claimed he met four groups and shot in self-defense, killing 17 people in total. He said all the dead had killed Brooks. However, the Warlpiri people estimated that 60 to 70 people were killed by the patrol.

On August 24, Murray captured an Aboriginal man named Arkirkra. He returned to Coniston, picked up Padygar, and marched them 240 km (150 mi) to Alice Springs. They arrived on September 1. Arkirkra and Padygar were charged with Brooks' murder. Murray was seen as a hero.

On September 3, Murray went to Pine Hill station to investigate cattle spearing. No records exist for this patrol, but he returned on September 13 with two prisoners.

Further Incidents

On September 16, Henry Tilmouth of Napperby station shot and killed an Aboriginal person he was chasing away. This incident was later investigated.

On September 19, Murray left again. This time, he was ordered to investigate an attack on a settler named William "Nuggett" Morton. Morton, a former circus wrestler, was known for being violent. He claimed 15 Warlpiri people attacked him at Broadmeadows Station.

Morton had gone to punish Aboriginal people for spearing his cattle. At Boomerang waterhole, he found a large Warlpiri camp. What happened there is unknown, but the Warlpiri decided to kill Morton. They surrounded his camp, and at dawn, 15 men attacked him. His dogs helped him, and he shot one attacker before the rest ran away. Morton returned to his main camp and was taken for treatment.

On September 24, a group including Murray, Morton, Alex Wilson, and Jack Cusack (who were of Aboriginal descent) began more patrols. Murray later described three incidents where 14 more Aboriginal people were reportedly killed. Morton identified all of them as his attackers.

The Warlpiri people say this patrol killed 15 people at Dingo Hole. They also tell how the patrol attacked a corroboree (a traditional Aboriginal gathering) at Tippinba. They rounded up many Aboriginal people, separated the women and children, and shot all the men. Some stories suggest up to 100 people were killed at these five sites.

Constable Murray returned to Alice Springs on October 18. He wrote a short official report, saying "drastic action had to be taken and resulted in a number of male natives being shot." He did not mention how many were killed or the details of the shootings.

Trial of Two Aboriginal Men

The trial of Arkirkra and Padygar for Brooks' murder took place in Darwin on November 7 and 8.

The first witness was 12-year-old Lolorrbra (Lala). He said he saw Arkirkra, Padygar, and Marungali kill Brooks. He also said all the Aboriginal people who helped them were now dead. Constable Murray then testified, but he spent too much time trying to justify his own actions. The judge had to remind him to stick to the facts about the accused.

The trial had problems. The judge dismissed the first jury because some jurors left for lunch. A new trial started the next day. This time, Lolorrbra's story was different and seemed coached. The judge also stopped the prosecution from using written confessions because of a legal error.

With no clear evidence of guilt, the judge ordered the jury to find Arkirkra and Padygar not guilty. The judge remarked, "It appears impossible for all those bands of natives to be associated with the murder of Brooks. It looks as if they were shot down at different places just to teach them and other aborigines a lesson."

A missionary named Athol McGregor was in the courtroom. He told church leaders about the killings. This led to pressure for a formal investigation. The Australian government was also under pressure from the British media and the League of Nations about how Aboriginal people were being treated.

Constable Victor Hall, another police officer, said Murray bragged about killing "closer to 70 than 17" people.

Board of Inquiry

A special Board of Inquiry was set up to investigate the events. It was led by police magistrate A. H. O'Kelly. However, some people felt the board was not fair from the start. One member was J. C. Cawood, Murray's boss, who had already said he thought "drastic action" was needed.

The board met for 18 days in January 1929. They looked into the deaths related to Brooks, Morton, and Tilmouth. In one more day, they finished their report. They found that 31 Aboriginal people had been killed and that each death was justified.

The inquiry claimed there was no drought in Central Australia and that there was plenty of food and water for Aboriginal people. This meant there was no reason for them to hunt cattle. However, a journalist who traveled with the board reported that the drought had destroyed the land. Settlers also reported losing most of their cattle to the drought.

O'Kelly later said that if he had known how the inquiry would turn out, he would not have taken the job. He felt that someone should have been punished for the killings.

Newspapers like Adelaide Register-News called Murray a hero. The Northern Territory Times said the police were completely cleared and that there was no evidence of a reprisal.

What Happened Later

Constable William George Murray stayed with the Northern Territory Police until the mid-1940s. He later died in Adelaide in 1975. William Morton moved away from the area a few years after the massacre. Bullfrog, who was accused of killing Brooks, was never arrested. He moved to Yuendumu and died of old age in the 1970s.

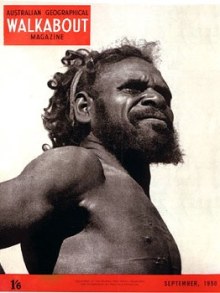

One of the few people who survived the massacre was Gwoya Jungarai. He left the area after his family was destroyed. A famous picture of him, known as One Pound Jimmy, later appeared on an Australian postage stamp.

Billy Stockman Tjapaltjarri, a well-known artist, also survived the massacre. His father was hunting and survived. His mother hid Billy in a coolamon (a traditional carrying dish) under a bush before she was shot and killed.

The strong stories passed down after the massacre are shown in paintings by some Indigenous artists. The Warlpiri, Anmatyerre, and Kaytetye people call this period The Killing Times. Other artists, like Rover Thomas, have also painted about similar massacres.

Seventy-fifth Anniversary

On October 9, 2003, Jack Ah Kit, a member of the Northern Territory Legislative Assembly, spoke about the massacre. He said that the late 1920s was a time of severe drought. This led to intense conflict over resources between the land's original people and the settlers with their cattle.

He explained that the Coniston massacre was not just one event. It was a series of violent attacks that happened over several weeks. Police parties killed people without caring who they were. He noted that even historians who deny frontier violence agree that many more people died than official records show.

The 75th anniversary of the massacre was remembered on September 24, 2003. The Central Land Council organized a ceremony near Yuendumu.

Documentary Film

In 2012, a film called Coniston was released. It was a docu-drama, meaning it combined documentary and drama. The film shared the oral histories and memories of elderly Aboriginal people, including descendants of those who were killed. Directed by David Batty and Francis Jupurrurla Kelly, the film was shown across Australia on ABC1 on January 14, 2013.

See also

- List of massacres in Australia

- List of massacres of indigenous Australians

- Caledon Bay crisis

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |