Hawkesbury and Nepean Wars facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hawkesbury Settlement |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Australian frontier wars | |||||||

Governor Arthur Phillip speared during a skirmish at Manly (1790). |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Indigenous clans:

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Pemulwuy † Tedbury † Yaragowhy † Woglomigh † Obediah Ikins Musquito (POW) John Wilson William Knight |

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

Armed settlers: 2,000+ Burreberongal Tribe (1790–1802) 100+ Combined total force: 3,600 |

Indigenous clan numbers: approx. 3,000 About 10+ armed Irish convicts 2 or more bushrangers |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Total Casualties: ~300 ('conservative estimate') Dead: at least 80 confirmed Wounded: bare minimum of 74 |

Dead: 80 confirmed (many likely went unrecorded) Wounded: +100 |

||||||

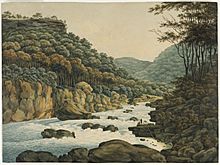

The Hawkesbury and Nepean Wars (1794–1816) were a series of fights. British soldiers and settlers fought against Aboriginal groups. These groups lived near the Hawkesbury River and west of Sydney. The wars began in 1794. This was when the British started building farms along the river. Some of these farms were set up by soldiers.

The local Darug people attacked farms and killed settlers. This continued until Governor Macquarie sent soldiers in 1816. These soldiers patrolled the Hawkesbury Valley. They ended the fighting by attacking an Aboriginal camp. This attack resulted in the deaths of 14 Aboriginal people. Aboriginal leaders like Pemulwuy also led attacks near Parramatta from 1795 to 1802. Because of these attacks, Governor Philip Gidley King made an order in 1801. This order allowed settlers to shoot Aboriginal people they saw in the Parramatta, Georges River, and Prospect areas.

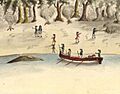

Sometimes, Aboriginal groups joined forces with British settlers. They did this to gain more land for their own tribes. But they would often quickly return to fighting the settlers. Most of the fighting used guerrilla tactics. This means small groups used surprise attacks. However, some larger battles also took place. The fighting ended with the defeat of the Aboriginal groups. They lost their lands along the Hawkesbury and Nepean rivers.

As European settlement grew, much land was cleared for farms. This destroyed the Aboriginal people's food sources. New diseases like smallpox also arrived. These things made Aboriginal groups angry at the settlers. This led to violent fights, often planned by leaders like Pemulwuy.

Contents

Why the Wars Started

Aboriginal People of the Sydney Area

The Sydney region was home to many Aboriginal nations. They shared a common language. These nations included the Eora along the coast, the Tharawal to the south, the Dharug to the northwest, and the Gandangara to the southwest. Each language group had several clans.

The Eora people had three main clans: the Cadigal, Wanegal, and Cammeraygal. They also had smaller clans. The Dharug people were the largest group in the Sydney region. They included clans like the Wangal, Kurrajong, Boorooberongal, Cattai, Bidjigal, Gommerigal, Mulgoa, Cannemegal, Bool-bain-ora, Cabrigal, Muringong, and Dural. A clan usually had between 50 and 100 people.

The British Colony in Australia

Britain lost its American colonies after the American Revolutionary War. This made Britain look for new places to set up colonies. In 1770, explorer James Cook claimed the east coast of Australia for Britain. So, Britain decided to create a penal colony there. This would help empty Britain's crowded jails. It would also stop France from gaining too much power in the Pacific.

The First Fleet arrived in 1788 at Port Jackson. This marked the start of Australia's colonization. The colony was first used to send criminals and political prisoners. But a few free settlers also came to live there. The colony was set up on the traditional land of the Cadigal people. The colony had about one thousand people. For the first few years, they struggled to live in the Australian climate.

Key Events of the Wars

Fighting on the Nepean and Hawkesbury Rivers (1814–1816)

We have more information about the fighting on the Nepean and Hawkesbury Rivers. This is because more free settlers, officials, and church leaders were writing things down. They were taking large land grants. A serious drought began in 1812. This put extra pressure on both settlers and Aboriginal people.

In February 1814, William Reardon was killed. He was likely mistaken for another man. This other man had accused some Aboriginal men of destroying his garden. In April 1814, several farms were attacked. These included Fernhill and Campbell's Shancarmore.

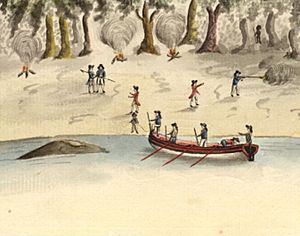

Fighting in 1814 in the Appin area focused on farms and individuals. An Aboriginal boy was killed by soldiers while taking corn. Warriors then drove off two soldiers. They killed another soldier named Eustace as he was reloading his gun. In response, settlers from Campbelltown shot into an Aboriginal camp. A woman and two children were killed.

In July 1814, two children on the Daly's Mulgoa farm were killed. This happened after Mrs. Daly shot at a group of Aboriginal people. Mrs. Daly and her baby were not harmed. The only conflict in 1815 was a man and woman being speared. This happened on Macarthur's Bringelly farm. It was due to an argument over a blanket.

The drought ended in January 1816. There were also several floods that year. Fighting started again in March 1816. Four men were killed while chasing Aboriginal warriors. The warriors had taken crops from Palmer's Bringelly farm. The next day, a man and woman were spared when warriors took crops from Wright's farm. An attack happened at the government camp at Glenroy. This was on the western side of the Blue Mountains. A government cart on its way there was also attacked. On the Grose River, Mrs. Lewis and a convict were killed. This was due to a dispute over wages. At the end of March, about eighty to ninety warriors attacked farms at Lane Cove.

In April 1816, Governor Macquarie sent out several groups of soldiers. Captain James Wallis went south to Appin. Captain Schaw went to the Hawkesbury. Lieutenant Dawe was sent to the Cow Pastures. Soldiers also protected the Glenroy supply depot. The guides' actions show how complex the fighting was. Schaw chased warriors around the Hawkesbury without success. After a white guide failed to help in a surprise attack, Schaw marched south. When Aboriginal guides realized Wallis's plan, they left him. A white guide named John Warby also disappeared from Wallis's group for a time.

The Appin Massacre happened because local settlers guided Captain Wallis to an Aboriginal camp. This camp had women and children near Broughton's farm. This suggests that attacks on Aboriginal people often happened when opportunities arose. The skull of an Aboriginal leader named Carnimbeigle ended up with a phrenologist in Edinburgh. Years later, William Byrne wrote that the bodies of sixteen Aboriginal people were beheaded. He also said the soldiers were rewarded for their actions.

Governor Macquarie's order in May 1816 told officials and soldiers to help settlers. They were to drive off hostile Aboriginal people. This order protected soldiers and settlers from murder charges. Serjeant Broadfoot searched the Nepean area twice in May. He reported no deaths. On his second trip, he met Magistrate Lowe with soldiers. This is the only report of Lowe being in the field. Four settlers were killed in June and July. Magistrate William Cox sent out soldiers, settlers, and native guides. They captured and killed Butta Butta, Jack Straw, and Port Head Jamie in mid-July. At least three of these men were killed without a trial. The fighting continued in August. Four Aboriginal children from the Hawkesbury were placed in the Native Institution. They were likely taken during unreported raids. In late August, two hundred of Cox's sheep and a shepherd were killed. The group sent to respond reported no deaths.

Aftermath of the Conflict

Settlers were forced from their Hunter Valley farms in late 1816. In September 1816, Magistrate William Cox shared his plan with Governor Macquarie. He wanted to send five groups of soldiers, settlers, and guides. They would search the Grose, Hawkesbury, and Nepean Rivers. There were no reports of Aboriginal deaths from these trips.

Despite the lack of reported deaths, fighting stopped on the Hawkesbury Nepean River system in 1816. Governor Macquarie gave out many rewards. Cox received payments in October 1816 and February 1817. Serjeant Broadfoot also received two payments. The guides received land grants for their help. Special breastplates were made for Aboriginal guides. Macquarie's report in April 1817 highlighted his success. But it did not mention any Aboriginal deaths.

Other records suggest something terrible happened to the Aboriginal people. The Macarthur family noted the absence of Aboriginal people when they returned in 1817. George Bowman's 1824 memo recalled soldiers killing Aboriginal people without caring who they were. Ministers Threlkeld and Lang both heard stories of killings on the Hawkesbury. Prosper Tuckerman recalled his father saying 400 Aboriginal people had been killed. In 1834, John Dunmore Lang wrote about the lasting impact of these events.

Images for kids

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |