Makassan contact with Australia facts for kids

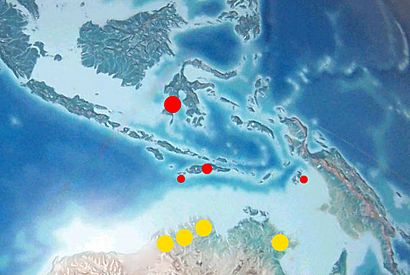

- Largest red dot: Makassar

- Other red dots (left to right): Rote, Timor, and Aru

- Three yellow dots: Kimberley

- Single yellow dot: Arnhem Land

The Makassar people came from Sulawesi, an island in Indonesia. They started visiting the northern coast of Australia around the mid-1700s. They first went to the Kimberley region, and later to Arnhem Land.

These visitors were mostly men. They collected and prepared trepang, also known as sea cucumber. This sea animal was very popular in China. People valued it for cooking and believed it had special health benefits. The name "Makassan" is used for all the people who came to Australia to collect trepang.

Contents

Collecting and Preparing Sea Cucumbers

Sea cucumbers are often called bêche-de-mer in French. In the Makassarese language, there are many different words for the 16 types of sea cucumbers. One Makassan word, taripaŋ, even became part of some Australian Aboriginal languages. For example, it became tharriba in Marrku and jarripang in Mawng.

Sea cucumbers live on the ocean floor. At low tide, they are easy to find. People traditionally caught them by hand, using spears, diving, or with nets. After catching them, the sea cucumbers were boiled. Then they were dried and smoked. This process helped keep them fresh for the long journey back to Makassar. From there, they were sold in markets across Southeast Asia, especially in China.

In 1803, explorer Matthew Flinders met a Makassan chief named Pobasso. Flinders wrote down how the Makassans prepared the sea cucumbers. This shows how important this trade was at the time.

Journeys to Marege' and Kayu Jawa

Makassan fleets started visiting Australia's northern coasts from Makassar around 1720, or maybe even earlier. Some historians think the trade began as early as 1640. Ancient Aboriginal rock art in Arnhem Land also suggests contact from the mid-1600s. Some drawings of boats in the rock art even suggest contact from the 1500s.

At its busiest, the trepang trade covered thousands of kilometers along Australia's northern shores. Makassan boats, called perahu or praus, arrived each December with the north-west monsoon winds. Each perahu could carry about 30 crew members. It's thought that around 1,000 trepangers came to Australia each year.

The Makassan crews set up temporary camps along the coast. Here, they would boil and dry the sea cucumbers. Four months later, they would sail home to sell their goods to Chinese traders. The Makassans called Arnhem Land Marege' (meaning "Wild Country"). They called the fishing areas in the Kimberley region Kayu Jawa. Other important fishing spots included West Papua, Sumbawa, Timor, and Selayar.

In 1803, Matthew Flinders met a Makassan fleet near what is now Nhulunbuy. He talked a lot with a Makassan captain, Pobasso, and learned about their trade. Another explorer, Nicolas Baudin, also saw many Makassan boats off Western Australia that same year.

The last Makassan trepanger to visit Australia was named Using Daeng Rangka. He lived a long life and his journeys are well known. He first came to Australia as a young man. He faced shipwrecks and had mostly good relationships with Aboriginal people. In 1883, he was the first trepanger to pay a license fee to the South Australian government. This fee made the trade less profitable. The trade slowly ended by the late 1800s, partly due to fees and too much fishing. The last Makassan perahu left Arnhem Land in 1907.

Signs of Makassan Visits

There is a lot of proof that Makassan fishers visited Australia. This proof can be seen in Aboriginal rock art and bark painting in northern Australia. Makassan perahu boats are often shown in these artworks.

Northern Territory Evidence

You can still find old Makassan processing sites from the 1700s and 1800s. These are at places like Port Essington and Groote Eylandt. You can also see tamarind trees that the Makassans brought to Australia. When people dig in these areas, they find pieces of metal, broken pottery, glass, coins, and fish-hooks.

In 2012, a small cannon was found at Dundee Beach near Darwin. Experts from the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory believe it came from Southeast Asia, probably Makassar. It doesn't look like Portuguese cannons. The museum has seven such cannons from Southeast Asia. Another cannon, found in Darwin in 1908, is at the South Australian Museum. It also might be from Makassar.

The Wurrwurrwuy stone arrangements at Yirrkala are important heritage sites. They show details of Makassan trepang fishing, including parts of their boats.

Western Australia Evidence

In 1916, two bronze cannons were found on a small island in Napier Broome Bay, Western Australia. Scientists at the Western Australian Museum studied them. They found that these cannons were small swivel guns. They were most likely made in Makassar in the late 1700s, not in Europe. Flinders' notes confirm that Makassans carried small cannons on their boats.

In 2021, archaeologists started digging on Niiwalarra Island off the Kimberley coast. They are working with the traditional owners of the island, the Kwini people. They have found pottery and other items. The Kwini people's oral histories also tell stories of Makassan fishers and traders on the island. Many old cooking areas show where trepang was boiled in large iron pots, especially around 1800.

Impact on Aboriginal People

The Makassan visits had a big impact on the culture of Aboriginal people. There were also influences going the other way. The Makassan contact greatly affected the Yolngu people of Arnhem Land. You can see it in their language, art, stories, and food.

According to anthropologist John Bradley, the contact between the two groups was successful. He said, "They traded together. It was fair – there was no racial judgement." Even today, Aboriginal communities in northern Australia celebrate this shared history. They remember it as a time of trust and respect.

However, some experts believe the first contact might have caused some trouble. They also note the influence of Islam on Aboriginal culture. Another anthropologist, Ian McIntosh, suggests that while Makassans were first welcomed, relations sometimes became difficult. He claims that Aboriginal people felt they were being used, which led to fighting.

Trade and Exchange

Studies show that Makassans talked with local Aboriginal people. They negotiated for the right to fish in certain waters. They traded things like cloth, tobacco, metal axes, knives, rice, and gin. The Yolngu people traded turtle-shell, pearls, and cypress pine. Some Aboriginal people also worked as trepangers. While much of the contact was peaceful, some was not. Daeng Rangka described a fight with Aboriginal people. Flinders was also warned by the Makassans to "beware of the natives."

Some rock art and bark paintings show that Aboriginal workers willingly went back to Makassar with the Makassans.

Health Impacts

Smallpox might have come to northern Australia in the 1820s through Makassan contact. However, smallpox was already spreading across Australia from Sydney.

Economic Changes

Some Yolngu communities in Arnhem Land changed how they lived. They started to rely more on the sea than the land. This happened after the Makassans introduced new technologies, like dug-out canoes. These strong boats were much better than the traditional Yolngu bark canoes. They allowed people to hunt dugongs and sea turtles in the ocean. The dug-out canoe and a type of spear found in Arnhem Land were based on Makassan designs.

Language Influence

A Makassan pidgin language became a common language along the north coast. It was used between Makassans and Aboriginal people. It was also used for trade between different Aboriginal groups. This helped different Aboriginal groups connect more. Words from the Makassarese language can still be found in Aboriginal languages of the north coast. For example, rupiah (money), jama (work), and balanda (white person).

Religious Influence

Some experts believe that parts of Islam were adopted by the Yolngu people. Muslim ideas can still be found in some ceremonies and Dreaming stories today. It's thought that the Makassans might have been the first to bring Islam to Australia.

According to anthropologist John Bradley, traces of Islam are clear in north-east Arnhem Land. He says, "If you go to north-east Arnhem Land there is [a trace of Islam] in song, it is there in painting, it is there in dance, it is there in funeral rituals." He adds that linguistic analysis shows "hymns to Allah, or at least certain prayers to Allah."

Current Situation

Even though Makassan fishing in Arnhem Land stopped, other Indonesian fishermen have continued to fish along the west coast. This has been happening for hundreds of years, even before Australia declared its current water boundaries. Some fishermen still use traditional boats passed down from their grandparents.

Today, the Australian government considers this fishing illegal. Since the 1970s, if these fishermen are caught, their boats are burned. The fishermen are then sent back to Indonesia. Most Indonesian fishing in Australian waters now happens around what Australia calls "Ashmore Reef".

See also

In Spanish: Contacto de Macasar con Australia para niños

In Spanish: Contacto de Macasar con Australia para niños

- Trepanging

- Patorani and padewakang, two types of perahu used for trepanging by Makassan

- History of Australia before 1901

- Yolngu

- Theory of Portuguese discovery of Australia

- Baijini, a legendary people interpreted by some researchers as pre-Makassan visitors to Arnhem Land.

- Marchinbar Island, location of a deposit of early coins in Australia

- Javanese contact with Australia

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |