Theory of the Portuguese discovery of Australia facts for kids

The theory of Portuguese discovery of Australia suggests that early Portuguese sailors were the first Europeans to see Australia. This happened between 1521 and 1524. This was long before the Dutch sailor Willem Janszoon arrived in 1606 on his ship, the Duyfken. Janszoon is usually thought to be the first European to discover Australia.

Even though there isn't widely accepted proof, this theory is based on a few ideas:

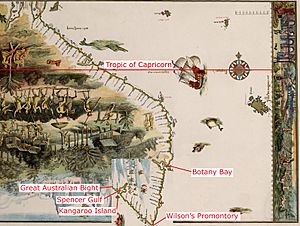

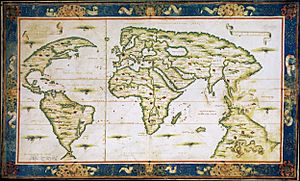

- The Dieppe maps are a group of French world maps from the 1500s. They show a large landmass between Indonesia and Antarctica. This land is called Java la Grande. It has names in French, Portuguese, and French-sounding Portuguese. Some people think this land matches Australia's northwestern and eastern coasts.

- Portuguese colonies were very close in Southeast Asia around 1513–1516. For example, Portuguese Timor is only about 650 kilometers from Australia's coast.

- Some old items found on Australian coastlines are thought by some to be from early Portuguese trips to Australia. However, most experts believe these items are proof of Makassan people visiting Northern Australia.

People have also claimed that sailors from China (Admiral Zheng), France, Spain, and even Phoenicia visited Australia first. But there is no widely accepted proof for these claims either.

Contents

How the Idea Started

Early Ideas in the 1800s

A Scotsman named Alexander Dalrymple wrote about this topic in 1786. But it was Richard Henry Major, who worked with maps at the British Museum, who first tried hard to prove the Portuguese visited Australia before the Dutch. This was in 1859. His main proof came from the Dieppe maps, a group of French maps from the mid-1500s.

However, many people today agree that Major's way of doing historical research was not good. His claims were often too strong. In 1861, Major said he found a map by Manuel Godinho de Eredia. He claimed it proved a Portuguese visit to North Western Australia, possibly in 1601. But this map was actually made in 1630. When Major finally read Erédia's writings, he realized the planned trip to lands south of Sumba in Indonesia never happened. Major took back his claims in 1873, but his reputation was damaged.

A Portuguese historian, Joaquim Pedro de Oliveira Martins, looked closely at Major's ideas. He decided that neither the "patalie regiã" on the 1521 world map by Antoine de La Sale nor "Jave la Grande" on the Dieppe Maps proved that Portuguese visitors were in Australia in the early 1500s. Instead, he thought this land feature on the maps came from descriptions of islands in the Sunda archipelago beyond Java. These descriptions were collected by the Portuguese from local people.

In 1895, George Collingridge wrote a book called The Discovery of Australia. He tried to trace all European efforts to find the Great Southern Land up to the time of Cook. He also shared his own ideas about the Portuguese visiting Australia, using the Dieppe maps. Collingridge spoke Portuguese and Spanish. He was inspired when copies of several Dieppe maps arrived in Australia. Libraries in Melbourne, Adelaide, and Sydney bought them. Even with some mistakes in place names, and theories that were "untenable" (meaning they couldn't be defended) to explain errors on the Dieppe maps, his book was a big effort. He wrote it when many maps and documents were hard to get, and document photography was new. However, Collingridge's theory was not popular. Professors G. Arnold Wood and Ernest Scott publicly criticized much of what he wrote. Collingridge made a shorter version of his book for schools in New South Wales, called The First Discovery of Australia and New Guinea. It was not used.

Professor Edward Heawood also criticized the theory early on. In 1899, he said that the idea of Australia's coasts being reached in the early 1500s relied almost completely on the guess that "a certain unknown map-maker drew a large land, with indications of definite knowledge of its coasts, in the quarter of the globe in which Australia is placed." He pointed out that "a difficulty arises from the necessity of supposing at least two separate voyages of discovery, one on each coast, though absolutely no record of any such exists." He added: "The difficulty, of course, has been to account for this map in any other way." He also noted that the way Japan was drawn on the Dieppe maps, and the made-up islands and coastlines, showed that these maps were not always reliable for distant parts of the world. He concluded: "This should surely make us hesitate to base so important assumption as that of a discovery of Australia in the sixteenth century on their unsupported testimony."

Kenneth McIntyre and the Theory in the 1900s

The idea of Portuguese discovery of Australia became much more popular because of Melbourne lawyer Kenneth McIntyre's 1977 book, The Secret Discovery of Australia; Portuguese ventures 200 years before Cook. McIntyre's book was printed again in a shorter paperback version in 1982 and 1987. By the mid-1980s, it was on school history reading lists. According to Tony Disney, McIntyre's theory influenced a generation of history teachers in Australian schools. A TV show was made about the book in the 1980s by Michael Thornhill. McIntyre and his theory were featured in many positive newspaper articles for the next twenty years. Australian history school textbooks also started to include his ideas.

Helen Wallis, who was the Curator of Maps at the British Library, visited Australia in the 1980s. Her support seemed to give academic weight to McIntyre's theory. In 1987, the Australian Minister for Science, Barry Jones, spoke at a meeting in Warrnambool. He said, "I read Kenneth McIntyre's important book... as soon as it appeared in 1977. I found its central argument... persuasive, if not conclusive." Other writers, like Ian McKiggan and Lawrence Fitzgerald, also came up with similar theories in the late 1970s and early 1980s. This also made the theory of Portuguese discovery of Australia seem more believable. In 1994, McIntyre was happy that his theory was becoming accepted in Australia: "It is gradually seeping through. The important thing is that... it has been on the school syllabus, and therefore students have... read about it. They in due course become teachers and... they will then tell their students and so on."

Possible Proof and Arguments

Cristóvão de Mendonça's Role

We know about Cristóvão de Mendonça from a few Portuguese writings. The most famous is by the historian João de Barros in Décadas da Ásia. This book tells the history of the Portuguese Empire growing in India and Asia, published between 1552 and 1615. Mendonça appears in Barros's story with orders to look for the legendary Isles of Gold. However, Barros then says Mendonça and other Portuguese sailors helped build a fort at Pedir (Sumatra). Barros does not mention the expedition again.

McIntyre suggested that Cristóvão de Mendonça led a trip to Australia around 1521–1524. He argued this trip had to be kept secret because of the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas. This treaty divided the undiscovered world into two halves for Portugal and Spain. Barros and other Portuguese sources do not mention finding land that could be Australia. But McIntyre guessed this was because original documents were lost in the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, or because of an official policy of silence.

Most people who support the theory of Portuguese discovery of Australia agree with McIntyre. They believe it was Mendonça who sailed down the eastern Australian coast. They think he made charts that ended up on the Dieppe maps, shown as "Jave la Grande" in the 1540s, 1550s, and 1560s. McIntyre claimed the maps showed Mendonça went as far south as Port Fairy, Victoria. Fitzgerald claims they show he went as far as Tasmania. Trickett says he went as far as Spencer Gulf in South Australia, and New Zealand's North Island.

Claims of Portuguese Words in Aboriginal Languages

In the 1970s and 1980s, a language expert named Carl Georg von Brandenstein looked at the theory from a different angle. He claimed that 60 words used by Aboriginal people in Australia's north-west came from Portuguese. According to Peter Mühlhäusler from the University of Adelaide:

"Von Brandenstein talks about some words in Pilbara [Aboriginal Australian] languages that sound like Portuguese (and Latin) words. He thinks about fifteen out of sixty might be borrowed from Portuguese or Latin. The strongest example is the word for 'turtle' in several Pilbara languages, which is 'tartaruga' or 'thartaruga'—the first one is exactly the same as the Portuguese word for this animal. These borrowed words must be from when the Portuguese first reached the Pilbara coast. They suggest the Portuguese did talk with the Aboriginal people there. However, there is still no proof that these contacts were strong or long enough to create a mixed language."

Von Brandenstein also claimed the Portuguese had a "secret colony... and cut a road as far as the present day town of Broome." He also said that "stone housing in the east Kimberley could not have been made without outside influence." However, Nicholas Thieberger says that modern language and archaeological research has not supported his ideas. Mühlhäusler agrees, saying that "von Brandenstein's proof is not convincing at all: his historical information is just guessing – since the colony was secret, there are no written records of it. His claims are not supported by the language evidence he uses."

Other Map and Text Evidence

In Australia today, reports of map and text evidence, and sometimes old objects, are sometimes said to "rewrite" Australian History. This is because they suggest a foreign presence in Australia. In January 2014, a gallery in New York listed a Portuguese manuscript from the 1500s for sale. One page had a drawing of an unknown animal in the margin. The gallery suggested it might be a kangaroo. Martin Woods from the National Library of Australia said: "The animal looks enough like a kangaroo or wallaby, but it could also be another animal in Southeast Asia, like many deer species.... For now, unfortunately, seeing a long-eared, big-footed animal in a manuscript doesn't really add much." Peter Pridmore from La Trobe University has suggested the drawing shows an aardvark.

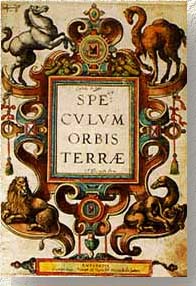

Speculum Orbis Terrae

Other old texts from the same time show a land south of New Guinea with different plants and animals. Part of a map in Cornelis de Jode's 1593 atlas Speculum Orbis Terrae shows New Guinea and a made-up land to the south where dragons live. Kenneth McIntyre thought that even though Cornelis de Jode was Dutch, the title page of Speculum Orbis Terrae might show that the early Portuguese knew about Australia. The page shows four animals: a horse for Europe, a camel for Asia, a lion for Africa, and another animal that looks like a kangaroo for a fourth continent. This last creature has a marsupial pouch with two babies inside. It also has the bent back legs typical of a kangaroo or other macropod family member. However, macropods (like the dusky pademelon, agile wallaby, and black dorcopsis) are found in New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago. So, this might not mean anything about a Portuguese discovery of Australia. Another idea is that the animal is based on a North American opossum.

James Cook and Cooktown Harbour

On June 11, 1770, James Cook's ship, the Endeavour, hit a coral reef (now called Endeavour Reef) off the coast of what is now Queensland. This was a very dangerous event, and the ship immediately started taking on water. However, over the next four days, the ship managed to slowly move along, looking for a safe place. In 1976, McIntyre suggested that Cook was able to find a large harbour (Cooktown harbour) because he had a copy of one of the Dieppe maps. McIntyre felt Cook's comment in his Journal, which he quoted as "this harbour will do excellently for our purposes, although it's not as large as I had been told," meant he had seen or was using a copy of the Dauphin Map. This would imply he was using it to guide his way along the eastern Australian coast. McIntyre admitted in his book that Cook might have been told this by a lookout or boat crew, but he called it a "peculiar remark." This idea stayed in later versions of The Secret Discovery of Australia.

In 1997, Ray Parkin edited a complete account of Cook's voyage from 1768–1771. He wrote down the Endeavour's original log, Cook's Journal, and other crew members' stories. Parkin wrote the relevant Journal entry as "...anchored in 4 fathom about a mile from the shore and then made a signal for the boats to come onboard, after which I went myself and buoy’d the channel which I found very narrow and the harbour much smaller than I had been told but very convenient for our purpose." The log for June 14 also says the ship's boats were checking the depth for the damaged Endeavour. Still, McIntyre's idea can still be seen in Australian school materials today.

Possible Evidence from Old Objects

Mahogany Ship

McIntyre believed that the remains of one of Cristóvão de Mendonça's ships, a caravel, were found in 1836. A group of whalers whose ship had sunk were walking along the sand dunes to the nearest town, Port Fairy. They found the wreck of a ship made of wood that looked like mahogany. Between 1836 and 1880, 40 people said they had seen an "ancient" or "Spanish" wreck. Whatever it was, the wreck has not been seen since 1880, even after many searches recently. Some recent writers have criticized McIntyre's accuracy in copying old documents to support his argument. Murray Johns' 2005 study of 19th-century stories about the Mahogany Ship suggests that the eyewitness accounts actually describe more than one shipwreck in the area. Johns concludes these wrecks were built in Australia in the early 1800s and are not related to Portuguese sailing.

The Geelong Keys

In 1847, at Limeburners Point, near Geelong, Victoria, Charles La Trobe, who liked studying rocks, was looking at shells and other sea deposits. These were uncovered by digging for lime production. A worker showed him a set of five keys. The worker claimed he found them the day before. La Trobe thought the keys had been dropped onto what was once the beach about 100–150 years earlier. Kenneth McIntyre guessed they were dropped in 1522 by Mendonça or one of his sailors. However, since the keys have been lost, their origin cannot be checked.

A more likely explanation is that the "very decayed" keys were dropped by one of the lime workers shortly before they were found. The layer of dirt and shells they were found under was dated to be around 2300–2800 years old. This makes La Trobe's dating unlikely. According to geologist Edmund Gill, and engineer and historian Peter Alsop, La Trobe's mistake is understandable. In 1847, most Europeans thought the world was only 6000 years old.

Cannon

In 1916, two bronze cannons were found on a small island in Napier Broome Bay, on the Kimberly coast of Western Australia. People mistakenly thought the guns were carronades, so the small island was named Carronade Island.

Kenneth McIntyre believed the cannons supported the theory of Portuguese discovery of Australia. However, scientists at the Western Australian Museum in Fremantle studied the weapons in detail. They found that they are swivel guns, and almost certainly from the late 1700s, made by Makassan people, not Europeans. The claim that one of the guns shows a Portuguese "coat of arms" is wrong.

In January 2012, a swivel gun found two years earlier at Dundee Beach near Darwin was widely reported by news websites and Australian newspapers as being Portuguese. However, later analysis by the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory showed it was also from Southeast Asia. Further analysis suggests the lead in the gun is most similar to lead from Andalusia in Spain. But it might have been reused in Indonesia. The museum has seven guns made in Southeast Asia in its collection. Another swivel gun from Southeast Asia, found in Darwin in 1908, is held by the Museum of South Australia. In 2014, it was found that sand inside the Dundee beach gun was dated to 1750.

Bittangabee Bay

Kenneth McIntyre first suggested in 1977 that the stone ruins at Bittangabee Bay were Portuguese. These ruins are in Beowa National Park near Eden on the south coast of New South Wales.

The ruins are the foundations of a building, surrounded by stone rubble. McIntyre argued this rubble might have once been a defensive wall. McIntyre also said he found the date 15?4 carved into a stone. McIntyre guessed that the crew of a Portuguese caravel might have built a stone blockhouse and defensive wall. They might have done this while staying for winter on a discovery trip down Australia's east coast.

Since McIntyre shared his theory in 1977, Michael Pearson has done a lot of research on the site. Pearson was a historian for the NSW Parks and Wildlife Service. Pearson found that the Bittangabee Bay ruins were built as a storehouse by the Imlay brothers. They were early European settlers who had whaling and farming businesses in the Eden area. The local Protector of Aborigines, George Augustus Robinson, wrote about the building starting in July 1844. The building was left unfinished when two of the three brothers died in 1846 and 1847.

Other visitors and writers, including Lawrence Fitzgerald, have not been able to find the 15?4 date. Peter Trickett wrote in Beyond Capricorn in 2007 that the date McIntyre saw might just be random marks in the stone.

Trickett accepts Pearson's work. But he guesses that the Imlays might have started their building on top of an old Portuguese structure. This would explain the surrounding rocks and partly shaped stones. Trickett also suggests the Indigenous Australian name for the area might have Portuguese origins.

Kilwa Sultanate Coins

In 1944, nine coins were found on Marchinbar Island by Maurie Isenberg, an RAAF radar operator. Four coins were identified as Dutch duits from 1690 to the 1780s. Five coins had Arabic writing and were identified as being from the Kilwa Sultanate of east Africa. The coins are now kept at the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney. In 2018, another coin, also thought to be from Kilwa, was found on a beach on Elcho Island. This is another of the Wessel Islands. It was found by archaeologist Mike Hermes, a member of the Past Masters group. Hermes thought this might show trade between Indigenous Australians and Kilwa. Or, that the coins arrived because of Makassan contact with Australia. Ian S McIntosh also believes the coins were "probably brought by sailors from Makassar... in the first wave of trepanging and exploration in the 1780s."

Arguments Against the Dieppe Maps Theory

Because there is a lot of guessing involved in the theory of Portuguese discovery of Australia, many people have criticized it. Matthew Flinders looked at the "Great Java" on the Dieppe maps in his book A Voyage to Terra Australis, published in 1814. He concluded: "it should appear to have been partly formed from vague information, collected, probably, by the early Portuguese navigators, from the eastern nations; and that conjecture has done the rest. It may, at the same time, be admitted, that a part of the west and north-west coasts, where the coincidence of form is most striking, might have been seen by the Portuguese themselves, before the year 1540, in their voyages to, and from, India".

In the last chapter of The Secret Discovery of Australia, Kenneth McIntyre challenged others. He said: "Every critic who seeks to deny the Portuguese discovery of Australia is faced with the problem of providing an alternative theory to explain away the existence of the Dieppe maps. If the Dauphin is not the record of real exploration, then what is it?"

The most active writer on this theory, and also its strongest critic, has been Flinders University Associate Professor W.A.R. (Bill) Richardson. He has written 20 articles about the topic since 1983. Richardson, an expert who speaks Portuguese and Spanish, first looked at the Dieppe maps to try and prove they were about Portuguese discovery of Australia. His criticisms are therefore very interesting. He says he quickly realized there was no link between the Dieppe maps and modern Australia's coastline: "The idea of an early Portuguese discovery of Australia relies completely on imagined similarities between the 'continent' of Jave La Grande on the Dieppe maps and Australia. There are no surviving Portuguese maps from the 1500s showing any land in that area. And there are no records at all of any trip along any part of the Australian coastline before 1606. People who support the Portuguese discovery theory try to explain away this embarrassing lack of direct proof by saying two things: the Portuguese had a secret policy, which must have been very effective, and the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, which they claim must have destroyed all the important old documents."

He dismisses the claim that Cristóvão de Mendonça sailed down the east coast of Australia as pure guesswork. This is because no details of such voyages have survived. In the same way, putting together parts of the "Jave La Grande" coastline to make it fit the real shape of Australia relies on another set of guesses. He argues that if you take that approach, "Jave La Grande" could be put together to look like anything.

Another part of Richardson's argument against the theory is about how it was researched. Richardson says that McIntyre's way of redrawing parts of maps in his book was misleading. He says that to make things clearer, McIntyre actually left out important features and names that did not support the Portuguese discovery theory.

Richardson's own view is that a study of placenames on "Jave La Grande" clearly shows it is connected to the coasts of southern Java and Indochina. Emeritus Professor Victor Prescott has said Richardson "brilliantly demolished the argument that Java la Grande show(s) the east coast of Australia." However, Australian historian Alan Frost recently wrote that Richardson's argument that the east coast of Java la Grande was actually the coast of Vietnam is "so speculative and convoluted as not to be credible" (meaning it's too much guessing and too complicated to believe).

In 1984, the book The Secret Discovery of Australia was also criticized by Captain A. Ariel, a master mariner. He argued that McIntyre had made serious mistakes in his explanation and measurement of "erration" (errors) in longitude. Ariel concluded that McIntyre was wrong on "all navigational... counts" and that The Secret Discovery of Australia was a "monumental piece of misinterpretation" (a huge mistake in understanding).

French map historian Sarah Toulouse concluded in 1998 that it seemed most reasonable to see la Grande Jave as purely the imagination of a Norman mapmaker.

In 2005, historian Michael Pearson made this comment about the Dieppe maps as proof of a Portuguese discovery of Australia: "If the Portuguese did indeed map the northern, western, and eastern coasts, this information was kept secret... The Dieppe maps had no claimed sources, no 'discoverer' of the land shown... and the pictures on the various maps are based on animals and people from Sumatra, not the reality of Australia. In this way, the maps did not really add to European knowledge of Australia. The way 'Jave La Grande' was shown had no more importance than any other guessed drawing of Terra Australis."

In a recent look at the Dieppe maps, Professor Gayle K. Brunelle of California State University, Fullerton argued that the Dieppe mapmakers were like advertisers for French geographic knowledge and land claims. The decades from about 1535 to 1562 (when the Dieppe mapmakers were most active) were also when French trade with the New World was at its highest in the 1500s. This included the North Atlantic fish trade, the fur trade, and, most importantly for the mapmakers, the competition with the Portuguese for control of the coasts of Brazil and the valuable brazilwood supplies. The bright red dye from brazilwood replaced woad as the main dye in the cloth industry in France and the Low Countries. The Dieppe mapmakers used the skills and geographic knowledge of Portuguese sailors, pilots, and geographers working in France. They made maps to highlight French interests and control over land in the New World that the Portuguese also claimed, both in Newfoundland and in Brazil. Brunelle noted that the design and style of the Dieppe maps mixed the newest knowledge in Europe with older ideas of world geography from Ptolemy and medieval mapmakers and explorers like Marco Polo. Renaissance mapmakers, like those in Dieppe, relied heavily on each other's work, and on maps from earlier generations. So their maps showed a mix of old and new information, often existing together in the same map in a confusing way.

Academic discussions about the Dieppe maps continue into the twenty-first century. In 2019, Professor Brian Lees and Associate Professor Shawn Laffan presented a paper. They argued that the Jean Rotz 1542 world map is a good "first approximation" (a rough but useful first drawing) of the Australian continent.

Map historian Robert J. King has also written a lot about this topic. He argues that Jave la Grande on the Dieppe maps reflects the way people understood the world in the 1500s. In 2010, King received an award for his writing about the origins of the Dieppe Maps. In an article published in 2022, King said there was no proof in Portuguese records and charts from the early 1500s that their sailors discovered Australia. He said that the large southern land, called Jave la Grande, or Terre de Lucac, on the world maps from the Dieppe school of mapmaking, which supporters of an early Portuguese discovery used as proof, could be explained. He explained it by looking at how ideas about the world and maps developed from Henricus Martellus to Gerard Mercator, from 1491-1569. The southern continent on the Dieppe maps, like Mercator’s southern continent with its part called Beach (Locach), was not found by French or Portuguese sailors. Instead, it was made up by guessing from a few misidentified or misplaced coasts in the southern part of the world.

After Magellan’s trip from 1519-1522, people mistakenly thought Marco Polo's Java Minor (Sumatra) was the island of Madura. This meant the southern coast of Java Major (Java) remained unclear. This was true even though the survivors of Magellan’s trip returned to Spain by going south of Java (Java Major), not through the strait between Madura and Java as understood from Antonio Pigafetta's story of the trip. This allowed mapmakers to call Java Major a part of Terra Australis and connect it with Marco Polo’s Locach. A changed version of Oronce Fine’s map from 1531 became the basis for the world maps of Gerardus Mercator and the Dieppe mapmakers. For them, the Regio Patalis, shown as a part of the Terra Australis on Fine’s map, was identified with Marco Polo's Java Major, or Locach (also known as Beach). The ysles de magna and ye. de saill, shown off the east coast of Jave la Grande on the Harleian map, which appear as I. de Mague and I. de Sally on André Thevet’s Quarte Partie du Monde, represent the two islands Magellan found during his trip across the Pacific in 1522. He called them the Desventuradas, or Islas Infortunatos (Unfortunate Isles). The Jave la Grande and Terre de Lucac on the Dieppe maps represented Marco Polo's Java Major and Locach. They were moved by the map-makers who misunderstood the information about Southeast Asia and America brought back by Portuguese and Spanish sailors. In a later article, he argues that the Dieppe mapmakers identified Java Major (Jave la Grande) or, in the case of Guillaume Brouscon Locach (Terre de lucac), with Oronce Fine's Regio Patalis.

See also

In Spanish: Teoría del descubrimiento de Australia por los portugueses para niños

In Spanish: Teoría del descubrimiento de Australia por los portugueses para niños