Gavin Menzies facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Gavin Menzies

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | Rowan Gavin Paton Menzies 14 August 1937 London |

| Died | 12 April 2020 (aged 82) |

| Occupation | Author, retired naval officer |

| Nationality | English |

| Genre | Pseudohistory |

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse | Marcella Menzies |

Rowan Gavin Paton Menzies (born August 14, 1937 – died April 12, 2020) was a British author. He was also a retired submarine officer in the Royal Navy. Menzies wrote books claiming that Chinese explorers sailed to America long before Christopher Columbus. However, most historians do not agree with Menzies' ideas. They consider his work to be pseudohistory, which means it looks like history but isn't based on solid facts.

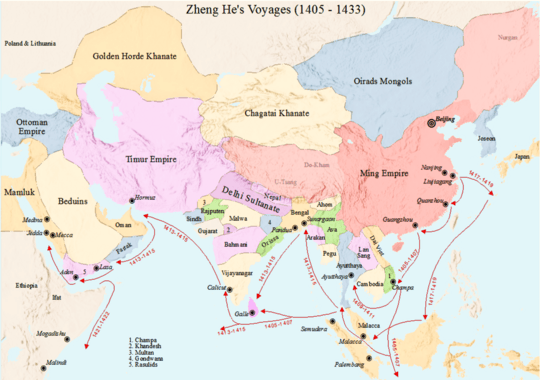

Menzies was most famous for his book 1421: The Year China Discovered the World. In this book, he suggested that the Chinese Admiral Zheng He and his huge fleet visited the Americas. This would have happened before Christopher Columbus's voyage in 1492. Menzies also claimed that this same Chinese fleet sailed all the way around the world. This would have been a century before Ferdinand Magellan's famous journey. His second book, 1434: The Year a Magnificent Chinese Fleet Sailed to Italy and Ignited the Renaissance, said that Chinese explorers also reached Europe. In his third book, The Lost Empire of Atlantis, Menzies claimed that the ancient city of Atlantis was actually the Minoan civilization. He believed it had a global sea empire that reached America and India thousands of years ago.

Contents

Gavin Menzies' Life Story

Gavin Menzies was born in London, England. His family moved to China when he was just three weeks old. He went to schools like Orwell Park Preparatory School and Charterhouse. Menzies left school when he was fifteen. He then joined the Royal Navy in 1953. He never went to university and did not have formal training in history.

From 1959 to 1970, Menzies served on British submarines. He claimed to have sailed the same routes as famous explorers like Ferdinand Magellan and James Cook. He said he did this while commanding the submarine HMS Rorqual from 1968 to 1970. Some critics have questioned if his claims about his sea voyages are true. Menzies often used his sailing experiences to support the ideas in his book 1421.

In 1959, Menzies said he was an officer on HMS Newfoundland. They sailed from Singapore to Africa, around the Cape of Good Hope, and then to Cape Verde before returning to England. Menzies believed the knowledge he gained about winds and currents on this trip was key. He used it to imagine the Chinese voyage he wrote about in his first book. However, some critics have doubted how deep his sailing knowledge really was.

In 1969, Menzies was involved in an accident in the Philippines. His submarine Rorqual hit a U.S. Navy minesweeper called USS Endurance. The Endurance was docked at a pier. The collision made a hole in the Endurance, but Rorqual was not damaged. An investigation found Menzies and one of his crew members responsible. This was due to several reasons, including a less experienced crew member steering the boat.

Menzies left the Navy the next year. He tried to become a politician in 1970. He ran as an independent candidate in Wolverhampton South West. He was against Enoch Powell and supported open immigration to Great Britain. He only received a very small number of votes (0.2%). In 1990, Menzies started researching Chinese maritime history. He had no academic training in history and did not speak Chinese. Critics say this stopped him from understanding original historical documents. Menzies later became an honorary professor at Yunnan University in China.

1421: The Year China Discovered the World

How the Book Was Written

Gavin Menzies got the idea for his first book after visiting the Forbidden City in Beijing, China. He was there with his wife Marcella for their twenty-fifth wedding anniversary. Menzies noticed that the year 1421 kept appearing. He thought it must have been a very important year in history. So, he decided to write a book about everything that happened in the world in 1421.

Menzies spent many years working on the book. When he finished, it was a huge book, about 1,500 pages long. He sent it to a literary agent named Luigi Bonomi. Bonomi told him it was too long to publish. But he was interested in a small part where Menzies talked about the voyages of Chinese Admiral Zheng He. Bonomi suggested Menzies rewrite the book, focusing only on Zheng He's journeys. Menzies agreed, but he said he wasn't a good writer. He asked Bonomi to rewrite the first three chapters for him.

Bonomi then contacted a public relations company. They helped get a major newspaper, The Daily Telegraph, to write an article about Menzies' ideas. Menzies rented a room at the Royal Geographical Society for this. After the article, publishers became very interested in his book. Bantam Press offered him £500,000 for the rights to publish it worldwide. At this point, Menzies' rewritten book was only 190 pages. Bantam Press thought the book could sell very well, but they felt it was not well-written. Menzies said they told him, "You know, if you want to get your story over, you've got to make it readable, and you can't write, basically."

During the editing process, more than 130 different people worked on the book. A large part of it was written by a ghostwriter named Neil Hanson. The authors relied completely on Menzies for facts. They did not use any fact checkers or well-known historians to make sure the information was correct. After all the rewriting, the book was about 500 pages long and ready to be published.

What the Book Claimed and How Well It Sold

The finished book was published in 2002. It was called 1421: The Year China Discovered the World. In the United States, it was called 1421: The Year China Discovered America. The book is written in a casual style. It tells stories of Menzies' travels around the world as he looked for "evidence" for his "1421 hypothesis." It also includes his ideas about Admiral Zheng He's fleet. Menzies says in the introduction that he wanted to answer a question: "On some early European world maps, it appears that someone had charted and surveyed lands supposedly unknown to the Europeans. Who could have charted and surveyed these lands before they were 'discovered'?"

In the book, Menzies decided that only China had the resources (time, money, people, and leaders) to send such big expeditions. He then tried to prove that the Chinese visited lands that no one in China or Europe knew about. He claimed that from 1421 to 1423, during China's Ming dynasty, Admiral Zheng He's fleets discovered many places. These included Australia, New Zealand, the Americas, Antarctica, and the Northeast Passage. He also said they sailed around Greenland, tried to reach the North and South Poles, and sailed around the world. This would have been before Ferdinand Magellan.

1421 quickly became a huge international success. It was translated into many languages and sold over a million copies. It was even on The New York Times best-seller list for several weeks in 2003.

The book has many footnotes and references. However, critics point out that it doesn't have strong evidence for Chinese voyages beyond East Africa. Most historians agree that East Africa was the farthest point of Zheng He's travels. Menzies based his main ideas on his own interpretations of DNA studies, old maps, and archaeological finds. Many of his ideas came from his personal sailing background, without other proof. Menzies claimed that the knowledge of Zheng He's discoveries was later lost. He believed this happened because government officials in the Ming court feared that more voyages would cost too much money and harm China's economy. He guessed that when the Yongle Emperor died in 1424, the new emperor stopped further expeditions. Menzies thought the officials then hid or destroyed records of past explorations to prevent more voyages.

Why Historians Disagreed

Most historians and experts on China have completely rejected 1421. They call the alternative history of Chinese exploration in the book "pseudohistory." A big point of disagreement is Menzies' use of maps. He used them to argue that the Chinese mapped both the Eastern and Western parts of the world in the 15th century.

A respected historian of exploration, Felipe Fernández-Armesto, strongly disagreed with Menzies' work. On July 21, 2004, the Public Broadcasting System (PBS) showed a two-hour documentary. It explained why all of Menzies' main claims were incorrect. This documentary featured professional Chinese historians. In 2004, historian Robert Finlay strongly criticized Menzies in the Journal of World History. He said Menzies handled evidence carelessly and made claims "without a shred of proof." Finlay wrote that Menzies' ideas were "without substance."

Tan Ta Sen, who leads the International Zheng He Society, said the book was popular but lacked historical accuracy. He commented, "The book is very interesting, but you still need more evidence. We don't regard it as an historical book, but as a narrative one. I want to see more proof. But at least Menzies has started something, and people could find more evidence."

A group of scholars and navigators from different countries also questioned Menzies' methods. They said his book 1421 was "a work of sheer fiction presented as revisionist history." They added that "Not a single document or artifact has been found to support his new claims on the supposed Ming naval expeditions beyond Africa." They concluded that Menzies' claims had been "thoroughly and entirely discredited by historians, maritime experts and oceanographers."

Menzies created a website where his readers could send him information that might support his ideas. He said his website was "a focal point for ongoing research into pre-Columbian exploration of the world." His fans sent him thousands of pieces of "evidence." However, academics have said all this "evidence" is not useful. They have also criticized how Menzies keeps getting support for his ideas, calling it "almost cult-like." Menzies has said that experts' opinions don't matter because "The public are on my side, and they are the people who count." A survey of History News Network readers ranked 1421 as one of the least believable history books available.

1434: The Year a Magnificent Chinese Fleet Sailed to Italy and Ignited the Renaissance

In 2008, Menzies released his second book. It was called 1434: The Year a Magnificent Chinese Fleet Sailed to Italy and Ignited the Renaissance. In this book, Menzies claimed that in 1434, Chinese groups reached Italy. He said they brought books and globes that greatly helped start the Renaissance. He also claimed that a letter written in 1474 by Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli, found among Columbus's private papers, showed that an earlier Chinese ambassador had directly communicated with Pope Eugene IV in Rome.

Menzies then suggested that ideas from the Chinese book Book of Agriculture (the Nong Shu), published in 1313, were copied by European scholars. He claimed these ideas directly inspired the drawings of machines that are usually credited to Italian thinkers like Taccola (1382–1453) and Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519).

Felipe Fernández-Armesto, a history professor, looked at Menzies' claim about Columbus's papers. He called this claim "drivel." He stated that no respected scholar supports the idea that Toscanelli's letter referred to a Chinese ambassador. Martin Kemp, a professor of art history at Oxford University, questioned Menzies' way of using historical facts. Regarding the European drawings supposedly copied from the Chinese Nong Shu, Kemp wrote that Menzies "says something is a copy just because they look similar. He says two things are almost identical when they are not."

Regarding Menzies' idea that Taccola's drawings were based on Chinese information, Captain P.J. Rivers pointed out a contradiction. Menzies himself said in his book that Taccola started his work on technical drawings in 1431. This was when Zheng He's fleet was still in China. He also said the Italian engineer finished his drawings in 1433, which was one year before the Chinese fleet supposedly arrived in Italy. Geoff Wade, a researcher at the Asia Research Institute, agreed that there was an exchange of ideas between Europe and China. However, he called Menzies' book historical fiction. He stated that there was "absolutely no Chinese evidence" for a sea journey to Italy in 1434.

Albrecht Heeffer looked into Menzies' claim that Regiomontanus based his solution to the Chinese remainder theorem on a Chinese work from 1247. Heeffer found that the solution method did not come from that text. Instead, it came from an earlier Chinese text called Sunzi Suanjing. This was also true for a similar problem solved by Fibonacci, which was even older than the 1247 Chinese text. Also, Regiomontanus could have used older methods involving tables from the abacus tradition.

See also

In Spanish: Gavin Menzies para niños

In Spanish: Gavin Menzies para niños

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |