1755 Lisbon earthquake facts for kids

|

|

| Local date | 1 November 1755 |

|---|---|

| Local time | 09:40 |

| Magnitude | 7.7–9.0 Mw (est.) |

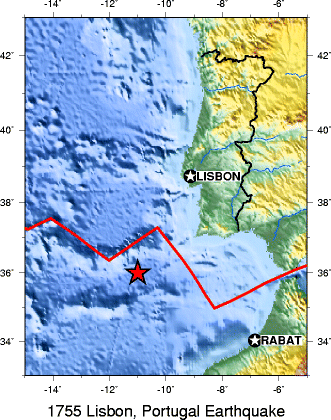

| Epicenter | 36°N 11°W / 36°N 11°W About 200 km (120 mi) west-southwest of Cape St. Vincent and about 290 km (180 mi) southwest of Lisbon |

| Fault | Azores–Gibraltar Transform Fault |

| Max. intensity | XI (Extreme) |

| Casualties | 12,000–50,000 deaths |

The 1755 Lisbon earthquake, also known as the Great Lisbon earthquake, was a huge natural disaster. It hit Portugal, Spain, and Northwest Africa on the morning of Saturday, November 1, 1755. This day was a special religious holiday called All Saints' Day.

The earthquake happened around 9:40 AM local time. Along with the fires and a giant wave called a tsunami that followed, it almost completely destroyed the city of Lisbon and nearby areas. Scientists believe the earthquake was very powerful, with a magnitude of 7.7 or even higher. Its center was in the Atlantic Ocean, about 200 kilometers (124 miles) west-southwest of Cape St. Vincent in Portugal.

This was the third major earthquake to hit Lisbon, after ones in 1321 and 1531. Experts think around 12,000 people died in Lisbon alone. This makes it one of the deadliest earthquakes in history. The event also caused big changes in Portugal's government and its empire. It made many thinkers in Europe, during a time called the Enlightenment, think deeply about life and religion. Because it was the first earthquake studied scientifically, it helped create modern seismology, which is the study of earthquakes.

Contents

What Happened During the Earthquake and Tsunami?

The earthquake struck on the morning of November 1, 1755, which was All Saints' Day. People who were there said the shaking lasted for three to six minutes. It caused cracks up to 5 meters (16 feet) wide in the middle of the city.

Many survivors ran to the open space near the docks to be safe. There, they saw the sea pull back, showing a muddy area with lost cargo and shipwrecks. About 40 minutes after the earthquake, a huge tsunami wave crashed into the harbor and downtown area. It rushed up the Tagus river so fast that people on horseback had to gallop away to higher ground to avoid being swept away. Two more waves followed this first one.

Candles lit in homes and churches for All Saints' Day fell over during the shaking. This started a massive fire that burned for hours across the city. The smoke and heat were so intense that people died from breathing problems even 30 meters (98 feet) away from the flames.

Lisbon was not the only city in Portugal affected. Many towns in the south, especially in the Algarve region, were badly damaged. The tsunami destroyed some forts along the coast. Most coastal towns in the Algarve were heavily damaged, except for Faro, which was protected by sandy banks. In Lagos, the waves reached the top of the city walls. Other towns like Peniche, Cascais, Setúbal, and even Covilhã (which is inland) were also hit by the earthquake or tsunami.

On the island of Madeira, the city of Funchal and smaller towns were greatly damaged. In the Azores islands, most ports were destroyed by the tsunami, with the sea reaching about 150 meters (492 feet) inland.

Former Portuguese towns in North Africa, like Ceuta and Mazagon, also felt the earthquake. The tsunami hit their coastal forts hard, sometimes even going over them and flooding the harbor. In Spain, tsunamis swept along the Atlantic Coast of Andalusia, damaging Cadiz.

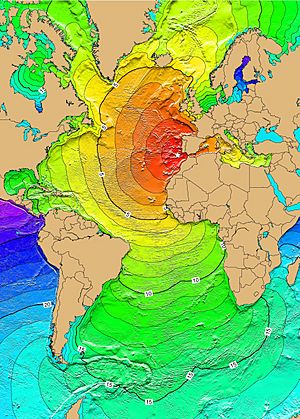

The earthquake's shaking was felt across Europe, as far away as Finland, and in North Africa. Some reports even say it was felt in Greenland and the Caribbean. Tsunamis as tall as 20 meters (66 feet) hit the coast of North Africa. Waves also reached Martinique and Barbados across the Atlantic Ocean. A 3-meter (10-foot) tsunami hit Cornwall on the southern coast of Britain. Galway, on the west coast of Ireland, was also hit, damaging part of its city wall.

In 2015, scientists found that tsunami waves might have even reached the coast of Brazil, which was a Portuguese colony back then. Letters from Brazilian officials at the time describe damage from huge waves.

Scientists agree that the earthquake's center was in the Atlantic Ocean, west of Portugal. Its exact spot was debated for a long time. Newer studies suggest it was closer to Portugal's coast to explain the tsunami's effects. A survey in 1992 found a large crack in the ocean floor southwest of Cape St. Vincent. This crack might have caused the main earthquake.

How Many People Were Affected and What Was Damaged?

A historian named Álvaro Pereira estimated that between 30,000 and 40,000 people died in Lisbon. At that time, Lisbon had about 200,000 residents. Another 10,000 people might have died in Morocco. Overall, Pereira estimated that 40,000 to 50,000 people died in Portugal, Spain, and Morocco from the earthquake, fires, and tsunami.

Eighty-five percent of Lisbon's buildings were destroyed. This included famous palaces and libraries. Most examples of Portugal's unique 16th-century Manueline architecture were lost. Many buildings that were not badly damaged by the earthquake were later destroyed by the fires. The new Lisbon opera house, which had opened only seven months before, completely burned down.

The Royal Ribeira Palace, located next to the Tagus river, was destroyed by the earthquake and tsunami. Inside, a royal library with 70,000 books was lost. Hundreds of artworks, including paintings by famous artists like Titian and Rubens, were also gone. The royal archives, which held detailed records of explorations by Vasco da Gama and other early sailors, disappeared.

Many important churches in Lisbon were damaged, such as the Lisbon Cathedral and the São Vicente de Fora. The Royal Hospital of All Saints, the largest hospital then, caught fire. Hundreds of patients sadly burned to death inside. The tomb of the national hero Nuno Álvares Pereira was also lost. Today, visitors to Lisbon can still see the ruins of the Carmo Convent. These ruins were kept as a reminder of the huge destruction.

How Lisbon Was Rebuilt After the Disaster

The royal family was safe from the disaster. King Joseph I of Portugal and his court had left the city to attend Mass outside Lisbon, as one of his daughters wished. After the earthquake, King Joseph I became afraid of living inside buildings. So, the court lived in a huge complex of tents and pavilions in the hills of Ajuda, which was then outside Lisbon. The king's fear never went away. Only after his death did his daughter, Maria I of Portugal, start building the royal Ajuda Palace on the site of the old tent camp.

The prime minister, Sebastião de Melo (who later became the Marquis of Pombal), also survived. When asked what to do, Pombal famously said, "Bury the dead and heal the living." He quickly started organizing help and rebuilding efforts. Firefighters were sent to put out the fires. Teams of workers and ordinary citizens were ordered to remove the thousands of dead bodies to prevent diseases from spreading. Against common practice and the Church's wishes, many bodies were put on boats and buried at sea. To keep order in the ruined city, the Portuguese Army was sent in. Gallows (structures for hangings) were built in high places to warn off looters; more than thirty people were publicly executed. The army also stopped many healthy citizens from leaving and made them help with the cleanup and rebuilding.

The king and prime minister immediately began rebuilding the city. On December 4, 1755, just over a month after the earthquake, Manuel da Maia, the chief engineer, showed his plans for rebuilding Lisbon. He offered four choices, from simply repairing the old city to building a completely new one. The king and his minister chose the boldest option: to completely clear the Baixa quarter (downtown area) and build new, wide, straight streets.

In less than a year, the city was cleared of all the rubble. The king wanted a new, perfectly organized city. So, he ordered the construction of large squares, straight, wide avenues, and broader streets.

The buildings designed in the Pombaline style are some of the first in Europe built to resist earthquakes. Small wooden models were made for testing. Earthquakes were simulated by having troops march around them to create vibrations. Lisbon's "new" downtown, known today as the Pombaline Lower Town (Baixa Pombalina), is now one of the city's famous attractions. Parts of other Portuguese cities, like Vila Real de Santo António in the Algarve, were also rebuilt using these Pombaline ideas.

The Casa Pia, a Portuguese organization for helping children, was founded after the social problems caused by the 1755 Lisbon earthquake.

How the Earthquake Changed Minds and Society

The earthquake had a huge impact on people's lives and on thinkers across Europe. It struck on an important religious holiday and destroyed almost every major church in Lisbon. This caused a lot of worry and confusion among the people of Portugal, who were very religious. Religious leaders and thinkers wondered if the earthquake was a sign of God's judgment.

Economy

A study in 2009 estimated that the earthquake cost Portugal between 32% and 48% of its total economic output (GDP). Even with strict rules, prices and wages changed a lot in the years after the disaster. The rebuilding efforts also led to higher pay for construction workers. More importantly, the earthquake became a chance to improve the economy and make Portugal less dependent on Britain.

Philosophy

The earthquake and its aftermath greatly influenced the smart thinkers of the European Age of Enlightenment. The famous writer and philosopher Voltaire used the earthquake in his book Candide and in his poem "Poem on the Lisbon disaster." Voltaire's Candide argued against the idea that everything happens for the best in this world, which was a popular belief at the time. The Lisbon disaster showed Voltaire that this idea might not be true.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was also affected by the disaster. He believed the earthquake was so severe because too many people lived too close together in the city. Rousseau used the earthquake as an argument against large cities, supporting a more natural way of life.

Immanuel Kant, another important philosopher, published three different writings about the Lisbon earthquake in 1756. When he was younger, he was fascinated by the earthquake. He gathered all the information he could from news reports and created a theory about what causes earthquakes. Kant's theory, which involved hot gases in huge underground caverns, was not correct. However, it was one of the first serious attempts to explain earthquakes using natural reasons instead of supernatural ones. Some say Kant's early book on the earthquake helped start scientific geography and seismology in Germany.

Politics

The earthquake had a major effect on politics. The prime minister, Sebastião de Melo, was the king's favorite. However, the old noble families of Portugal did not like him because they saw him as a newcomer. The prime minister, in turn, disliked these old nobles, thinking they were corrupt and unable to get things done. Before November 1, 1755, there was a constant fight for power. But the Marquis of Pombal's quick and effective response to the disaster greatly increased his power and reduced the influence of the old noble groups.

The Birth of Modern Earthquake Science

The prime minister's actions were not just about rebuilding. He ordered a survey to be sent to all churches in the country asking about the earthquake and its effects. Some of the questions included:

- When did the earthquake start, and how long did it last?

- Did the shaking feel stronger from one direction than another? For example, from north to south? Did buildings fall more to one side?

- How many people died, and were any of them important people?

- Did the sea rise or fall first, and how much did it rise above normal?

- If a fire started, how long did it burn and what damage did it cause?

The answers to these questions are still kept in the Torre do Tombo, Portugal's national historical archive. By studying and comparing the priests' reports, modern scientists have been able to understand the event from a scientific point of view. Without the questionnaire designed by the Marquis of Pombal, this would have been impossible. Because he was the first to try to describe an earthquake's causes and effects in a scientific way, the Marquis of Pombal is seen as a very important figure in the history of modern earthquake science.

See also

In Spanish: Terremoto de Lisboa de 1755 para niños

In Spanish: Terremoto de Lisboa de 1755 para niños

- 1722 Algarve earthquake

- 1755 Cape Ann earthquake

- 1761 Portugal earthquake

- Azores–Gibraltar Transform Fault

- Earthquake Baroque

- List of earthquakes in Portugal

- List of historical earthquakes

- List of megathrust earthquakes

- List of historical tsunamis

- Southwest Iberian Margin

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |