Oronce Fine facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Oronce Fine

|

|

|---|---|

Oronce Fine

|

|

| Born | 20 December 1494 Briançon, France

|

| Died | 8 August 1555 (age 60) Paris, France

|

| Nationality | French |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Cartography, mathematics |

Oronce Fine (born December 20, 1494 – died August 8, 1555) was a very smart French person. He worked as a mathematician, a cartographer (someone who makes maps), an editor, and a book illustrator. In Latin, his name was Orontius Finnaeus.

Contents

Life of Oronce Fine

Oronce Fine was born in Briançon, France. His father and grandfather were both doctors, so he grew up in a family that valued learning. He studied in Paris at the Collège de Navarre and became a doctor in 1522.

Fine's father was also very interested in science, especially astronomy. He even made many tools for studying the stars and published a book about astronomy. This helped shape Oronce Fine's early life and his love for science.

His university in Paris was a top place for studying philosophy and religion. There, Fine became very good at editing. He later helped print many books written by other scholars. In 1524, he was put in prison for reasons that are still debated today.

In 1531, King Francis I chose him to be the first professor of mathematics at the Collège Royal. This college is now known as the Collège de France. Fine taught there until he passed away.

As the first math professor, he became one of the most important mathematicians in France. One of his biggest achievements was a collection of his work called Protomathesis. This book covered four main areas of mathematics. Fine was seen by his friends as more than just a mathematician. He also made scientific tools and helped manage printing houses in Paris. He inspired many students, including Pedro Nunes and Petrus Ramus, to continue their studies.

Even though he left behind many important math papers, Fine often had money problems and legal issues. He worked as an illustrator and proofreader for printing companies in Paris. He hoped this would help support his six children after his father died. Sadly, his efforts were not enough, and his family faced poverty after he died. To make things even harder, his wife passed away soon after him.

Fine's Contributions to Mathematics

Oronce Fine is well known for his work in mathematics. Many historians see him as the first royal lecturer to teach mathematics. He wasn't famous for discovering new math ideas, but for making math popular across France. His job was to make math easier to understand and to improve how it was taught. Fine had to include practical math skills that could be used in other fields like medicine, law, and religion.

To show his new ways of teaching, he published his work in Protomathesis. This collection included his lessons on practical math, not just traditional math. Protomathesis also combined both practical and theoretical teachings. This was completely new for France and changed how mathematics was taught and seen. His studies and teachings helped him work in many math areas. These included practical geometry, arithmetic, optics, how to make sundials, astronomy, and making instruments.

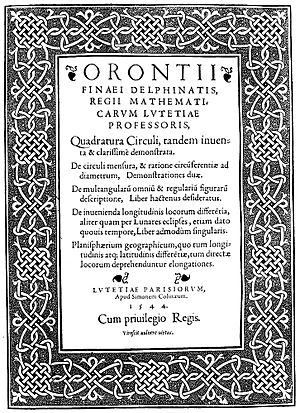

One idea Fine suggested, which is still used today, is the value of pi. In 1544, he said pi was about 3.1746. Later, he gave other values, and in his book De rebus mathematicis (1556), he gave a value close to 3.1410.

Astronomy and Geography Work

In 1542, Fine published De mundi sphaera, which means On the Heavenly Spheres. This was a popular textbook about astronomy. Its woodcut pictures were very well liked. His writings on astronomy included guides on how to use tools and methods for studying the sky. For example, he wrote about how to find longitude by watching eclipses of the Moon from two different places. He also described newer inventions, like a tool he called a méthéoroscope. This was an astrolabe with a compass added to it.

Fine also made his own direct contributions. His woodcut map of France from 1525 was one of the first of its kind. In 1524, he built a sundial out of ivory, which you can still see today.

Fine's heart-shaped map from 1531 is probably his most famous drawing. Other well-known mapmakers, like Peter Apian and Gerardus Mercator, often used it.

Fine tried to connect new discoveries in the New World with old stories and information from Ptolemy about the East. For example, on one of his world maps from 1531, the name "Asia" covered both North America and Asia. He showed them as one large landmass. He used the name "America" for South America. On the same map, Fine drew a large southern landmass called Terra Australis. He wrote that it was "recently discovered but not yet completely explored." This referred to Ferdinand Magellan's discovery of Tierra del Fuego.

Fine's ideas about the world came from a German mathematician named Johannes Schöner. Experts have found that Fine's world map was very similar to Schöner's globes. This shows that Fine likely used Schöner's work as a guide.

Legacy and Recognition

Oronce Fine died in Paris when he was 60 years old.

A famous painter named Jean Clouet is thought to have painted a picture of Fine in 1530. The original painting is now lost, but we know what it looked like from copies made from it.

The lunar crater Orontius on the Moon and Finaeus Cove in Antarctica are both named after Oronce Fine. These names use his Latinized name, Orontius. In 2014, a public square in Paris, France, was also named after Oronce Fine.

See also

In Spanish: Oronce Finé para niños

In Spanish: Oronce Finé para niños

- Charles Hapgood

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |