Dugong facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Dugong |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: |

Dugongidae

Gray, 1821

|

| Subfamily: |

Dugonginae

Simpson, 1932

|

| Genus: |

Dugong

Lacépède, 1799

|

| Species: |

D. dugon

|

| Binomial name | |

| Dugong dugon (Müller, 1776)

|

|

|

|

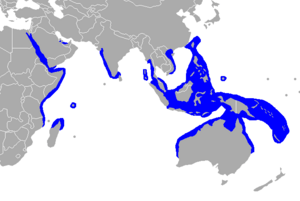

| Natural range of D. dugon. | |

The dugong (Dugong dugon) is a large mammal that lives its entire life in the sea. People sometimes call them "sea cows" because they eat a lot of seagrass. They live in warm, shallow ocean areas where seagrass grows. This includes the northern coast of Australia, and parts of the Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean.

Dugongs are more closely related to elephants than to other sea animals. Their closest relative in the water is the manatee. Manatees live in freshwater in America and West Africa.

A dugong can grow to about 3 m (10 ft) long and weigh up to 400 kg (882 lb). They only come to the surface to breathe. Unlike seals, they never go onto land. A baby dugong is called a calf. It drinks milk from its mother until it is about two years old. Dugongs become adults between 9 and 17 years old. They can live for up to 70 years. Dugongs are grey to brown in color. They have a tail like a whale and flippers. They do not have a dorsal fin like a shark. They have a wide, flat nose, small eyes, and small ears.

Dugongs are slow-moving animals that can travel long distances. Studies show that some dugongs travel over 560 kilometres (348 mi). Scientists think they move to find food, especially if storms affect seagrass. Males might follow females or look for their own areas. If the water gets too cold (below 17 degrees Celsius), they will move to warmer places. Because of their size, only sharks, saltwater crocodiles, and killer whales attack dugongs.

Contents

About the Dugong's Body

The dugong's body is large and shaped like a cylinder. It gets narrower at both ends. They have thick, smooth skin that is pale cream when they are born. As they get older, their skin turns brownish-grey. Their color can also change if algae grows on their skin. They have short, sparse hair, especially around their mouth. This hair helps them feel their surroundings. Their large, horseshoe-shaped upper lip is very flexible. This muscular lip helps them find and eat food.

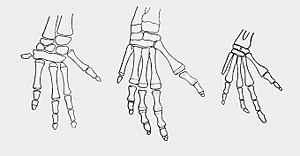

A dugong's tail and flippers are like those of dolphins. They move their tail up and down in long strokes to swim forward. They can twist their tail to turn. Their front limbs are paddle-like flippers. These help them turn and slow down. Dugongs do not have nails on their flippers. Their flippers are only about 15% of their body length. Their tail has deep notches.

A dugong's brain weighs about 300 g (11 oz). This is only about 0.1% of its body weight. Dugongs have very small eyes, so their vision is not great. However, they have excellent hearing within certain sound ranges. Their ears do not stick out and are on the sides of their head. Their nostrils are on top of their head and can close with valves. Male and female dugongs look very similar. Their lungs are very long, reaching almost to their kidneys. Their kidneys are also long to help them live in saltwater. If a dugong gets hurt, its blood clots quickly.

The dugong's skull is unique. It is large with a sharply downward-curved upper jaw. This part is stronger in males. Their spine has between 57 and 60 vertebrae. Unlike manatees, a dugong's teeth do not keep growing back. Males grow two incisors (tusks) during puberty. Female tusks grow but usually do not stick out until later in life. The number of growth rings in a tusk can tell us a dugong's age. Their cheek teeth also move forward as they age.

Adult dugongs rarely grow longer than 3 metres (9.8 ft). A dugong this long would weigh about 420 kilograms (926 lb). Most adults weigh between 250 kilograms (551 lb) and 900 kilograms (1,984 lb). The largest dugong ever recorded was 4.06 metres (13.32 ft) long and weighed 1,016 kilograms (2,240 lb). This one was found off the coast of west India. Females tend to be larger than males.

Where Dugongs Live

Dugongs live in warm coastal waters. Their range stretches from the western Pacific Ocean to the eastern coast of Africa. This covers about 140,000 kilometres (86,992 mi) of coastline. They are usually found between 26 and 27 degrees north and south of the equator. They used to live in more places, but their populations are now spread out. Today, dugongs are found in the waters of 37 countries. Scientists believe the total number of dugongs is shrinking. The worldwide population has dropped by 20% in the last 90 years. They have disappeared from places like Hong Kong, Mauritius, and Taiwan. More disappearances are likely.

Dugongs usually live in warm coastal waters. They gather in large numbers in wide, shallow, protected bays. The dugong is the only mammal that lives only in the sea and eats only plants. Manatees, for example, also use freshwater. Dugongs can live in brackish water (a mix of fresh and salt water) found in coastal wetlands. Many are also found in wide, shallow mangrove channels and near large islands where seagrass beds are common. They usually stay at a depth of about 10 m (33 ft). However, in some areas, they have been seen over 10 kilometres (6 mi) from shore. They can dive as deep as 37 metres (121 ft) to find deepwater seagrass. Shallow waters are used for giving birth, which helps protect the babies from predators. Deeper waters might offer a warm place to stay during winter.

Dugongs in Different Regions

In the late 1960s, groups of up to 500 dugongs were seen off East Africa. Now, populations there are very small, often 50 or fewer. They might even disappear from these areas. The eastern side of the Red Sea has large populations, possibly hundreds. The Persian Gulf has the second-largest dugong population in the world, with about 7,500 individuals. However, recent studies show that these numbers are also going down.

A small, isolated group of dugongs lives in the Marine National Park, Gulf of Kutch in western India. This group is far from other dugong populations. Some populations in this area, like those near the Maldives, are now thought to be gone. There is a population between India and Sri Lanka, but it is very small.

In the southern Pacific, outside of Australia, a small population lives along the southern coast of China. Efforts are being made to protect them, but their numbers are still decreasing. In Vietnam, dugongs are mostly found around Phu Quoc Island and Con Dao Island. Con Dao is now the only place in Vietnam where dugongs are regularly seen. In Thailand, dugongs are found in 6 provinces along the Andaman Sea. Very few are left in the Gulf of Thailand. Small numbers are also believed to live in the Straits of Johor and around Borneo. The Solomon Islands and New Caledonia also have dugongs.

The smallest and northernmost dugong population lives around the Ryūkyū Islands in Japan. There are fewer than 50 dugongs left here, possibly as few as three. New sightings of a mother and calf in 2017 suggest they might be breeding. Historically, many dugongs lived in the Yaeyama Islands. However, hunting and destructive fishing methods after World War II greatly reduced their numbers. Populations around Taiwan are almost gone.

Dugongs in Australia

Australia has the largest dugong population in the world. They live from Shark Bay in Western Australia to Moreton Bay in Queensland. Shark Bay has a stable population of over 10,000 dugongs. More than 20,000 dugongs live in the gulf of Carpentaria. Over 25,000 live in the Torres Strait. The Great Barrier Reef is an important feeding area for dugongs, with about 10,000 living there. Large bays along the Queensland coast also provide important homes for dugongs.

Extinct Mediterranean Population

Dugongs once lived in the Mediterranean Sea. This population likely came from the Red Sea. However, due to geography and climate change, this group was never very large and eventually died out.

Dugong Life and Habits

Dugongs live a long time. The oldest one recorded was 73 years old. They have few natural predators. Crocodiles, killer whales, and sharks can threaten young dugongs. Dugongs can also get many infections and diseases. About 30% of dugong deaths in Queensland since 1996 are thought to be from disease.

Dugongs are social animals, but they are usually found alone or in pairs. This is because seagrass beds cannot support very large groups. Sometimes, hundreds of dugongs gather, but only for a short time. They are shy and do not often approach humans, so we don't know much about their behavior. They can hold their breath for six minutes, though two and a half minutes is more common. They have been seen resting on their tails with their heads above water to breathe. They can dive up to 39 metres (128 ft) deep, but they spend most of their lives no deeper than 10 metres (33 ft).

Dugongs communicate with chirps, whistles, barks, and other sounds underwater. Different sounds might have different meanings. They don't rely much on sight because their eyesight is poor. Mothers and calves stay in close physical contact. Calves often touch their mothers with their flippers for comfort.

Dugongs are semi-nomadic. They often travel long distances to find food, but they usually stay within a certain area their whole lives. Large groups sometimes move together. These movements are likely due to changes in how much seagrass is available. Their good memory helps them return to specific places after long journeys. Daily movements are affected by the tides. In areas with big tides, dugongs travel with the tide to reach shallower feeding areas. In colder areas, dugongs travel to warmer waters during winter. Sometimes, individual dugongs make very long journeys over deep ocean waters. One was seen as far south as Sydney. Even though they are sea creatures, dugongs have been known to travel up creeks. One was found 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) up a creek near Cooktown.

What Dugongs Eat

Dugongs are called "sea cows" because they mainly eat seagrass. When they eat, they usually swallow the whole plant, including the roots. If they can't, they will just eat the leaves. Scientists have found many types of seagrass in dugong stomachs. They will also eat algae if seagrass is scarce. Although they are mostly herbivores (plant-eaters), they sometimes eat small invertebrates like jellyfish or shellfish. Dugongs in some areas, like Moreton Bay, Australia, will eat invertebrates or marine algae when their favorite grasses are low.

Most dugongs do not feed in very thick seagrass areas. They prefer places where the seagrass is sparser. The type of seagrass is important. They prefer grasses that are low in fiber, high in nitrogen, and easy to digest. In the Great Barrier Reef, dugongs eat low-fiber, high-nitrogen seagrasses to get the most nutrients. They prefer younger seagrass that grows quickly in open spaces. Dugongs can actually change the types of seagrass in an area by their feeding habits.

Because their eyesight is not good, dugongs often use their sense of smell to find food. They also have a strong sense of touch. They feel their surroundings with their long, sensitive bristles. They will dig up a whole plant, shake off the sand, and then eat it. They have been known to gather a pile of plants before eating them. Their flexible and muscular upper lip helps them dig out the plants. This leaves furrows, or tracks, in the sand where they have been.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

A dugong becomes an adult between the ages of eight and eighteen. This is older than most other mammals. Males show they are mature when their tusks grow out. Females give birth only a few times in their lives, even though they can live for 50 years or more. They spend a lot of time caring for their young. The time between births can be from 2.4 to 7 years.

Females are pregnant for 13–15 months. They usually give birth to just one calf. Birth happens in very shallow water, sometimes almost on the shore. As soon as the calf is born, the mother pushes it to the surface to take its first breath. Newborns are already 1.2 metres (4 ft) long and weigh about 30 kilograms (66 lb). They stay close to their mothers, which might make swimming easier. The calf drinks milk for 14–18 months, but it starts eating seagrass soon after birth. A calf will only leave its mother once it is fully grown.

Dugongs and People

Historically, dugongs were easy targets for hunters. People hunted them for their meat, oil, skin, and bones. Some cultures believed dugongs were the inspiration for mermaids. People around the world developed traditions around dugong hunting. In some places, dugongs are still very important. A growing tourism industry around dugongs helps the economy in some countries.

There is a 5,000-year-old cave painting of a dugong in Tambun Cave, Ipoh, Malaysia. This painting was made by ancient people. During the Renaissance and Baroque eras, dugongs were sometimes shown in special collections of rare items. They were also presented as Fiji mermaids in shows.

Dugong meat and oil were traditionally very valuable foods for Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders. Some Aboriginal Australians see dugongs as part of their identity. Dugongs also play a role in legends in Kenya, where they are called the "Queen of the Sea." Their body parts are used for food, medicine, and decorations. In some areas, dugong oil is used to preserve wooden boats. In Japan, dugong ribs were used for carvings. In Southern China, dugongs were seen as "miraculous fish," and it was bad luck to catch them. However, hunting for food increased after the 1950s. In the Philippines, dugongs are thought to bring bad luck, and parts of them are used to ward off evil spirits. In parts of Thailand, people believe dugong tears make a powerful love potion. In parts of Indonesia, they are thought to be women who have been reborn. In Papua New Guinea, they are a symbol of strength.

Some believe that dugong hides were used as coverings for the Old Testament worship tent called the Tabernacle.

Protecting Dugongs

Dugong numbers have gone down recently. For a dugong population to stay healthy, 95% of adults must survive each year. Humans can only hunt 1–2% of females without harming the population. This number is even lower if there isn't enough food for calves. Even in the best conditions, a population is unlikely to grow more than 5% a year. This makes dugongs very vulnerable to over-hunting. Since they live in shallow waters, human activities put a lot of pressure on them. Research on dugongs and human impact has been limited, mostly in Australia. In many countries, dugong numbers have never been counted. So, we need more information to manage them well. The only long-term data comes from the coast of Queensland, Australia. A major study in 2002 found that dugongs were declining and possibly gone from one-third of their range. Their status in another half of their range was unknown.

Human Impact on Dugongs

Even though dugongs are protected by law in many countries, their numbers are still decreasing. The main reasons are human activities like hunting, habitat loss, and deaths from fishing. Getting caught in fishing nets causes many deaths, but we don't have exact numbers. Most problems with large-scale fishing happen in deeper waters where dugongs are few. Local fishing is the main risk in shallower waters. Since dugongs cannot stay underwater for very long, they can easily drown if caught in nets. Shark nets used to cause many deaths, but they have been replaced with baited hooks in most areas. Hunting has also been a problem. While most areas no longer hunt them, some indigenous communities still do. In northern Australia, hunting is still the biggest impact on dugong populations.

Boat strikes are a problem for manatees, but we don't know how much they affect dugongs. More boat traffic increases the danger, especially in shallow waters. Ecotourism has grown in some countries, but its effects are not fully known. It has caused problems in places like Hainan due to damage to the environment. Modern farming and more land clearing also affect dugong habitats. Many coastal areas where dugongs live are becoming more industrialized, with more people. Dugongs collect heavy metals in their bodies over time, more than other sea mammals. The effects of this are unknown. International efforts to protect dugongs exist, but social and political needs in many developing countries make it hard. Shallow waters are often used for food and income, and aid meant to improve fishing can make problems worse. In many countries, there are no laws to protect dugongs, or the laws are not enforced.

Oil spills are a danger to dugongs in some areas, as is land reclamation (creating new land from the sea). In Okinawa, the small dugong population is threatened by United States military activity. Plans to build a military base near the Henoko reef could harm the dugongs. Military activity also brings noise pollution, chemical pollution, soil erosion, and exposure to depleted uranium. Some Okinawans have fought these plans in US courts because of concerns about the environment and dugong habitats. It was later found that the Japanese government was hiding evidence of how ship lanes and human activities negatively affected dugongs near Henoko reef. One of the three dugongs there has not been seen since June 2015, when digging began.

Environmental Damage

If dugongs do not get enough food, they may give birth later and have fewer young. Food shortages can happen for many reasons. These include habitat loss, seagrass dying or becoming unhealthy, and human activity disturbing their feeding. Sewage, detergents, heavy metals, salty water, herbicides, and other waste products all harm seagrass meadows. Human activities like mining, trawling (fishing with large nets), dredging (clearing the seabed), land reclamation, and boat propellers also increase sedimentation. This smothers seagrass and blocks sunlight, which is the biggest threat to seagrass.

Halophila ovalis, a type of seagrass dugongs prefer, dies quickly without light. It can die completely in 30 days. Extreme weather like cyclones and floods can destroy hundreds of square kilometers of seagrass meadows. They can also wash dugongs ashore. It can take over ten years for seagrass meadows to recover or spread into new areas. Most protection efforts involve limiting activities like trawling in seagrass areas. However, little is done about pollution coming from land. In some areas, water becomes saltier due to wastewater, and it's unknown how much salt seagrass can handle.

Dugong habitat in the Oura Bay area of Henoko, Okinawa, Japan, is currently threatened. The Japanese government is doing land reclamation to build a US Marine base there. In August 2014, initial drilling was done near the seagrass beds. This construction is expected to seriously damage the dugong population's home, possibly leading to them disappearing from that area.

Dugongs in Captivity

The Australian state of Queensland has sixteen dugong protection parks. Some areas are preservation zones where even Aboriginal Peoples are not allowed to hunt. Capturing dugongs for research has caused only one or two deaths. Dugongs are expensive to keep in captivity. This is because mothers and calves spend a long time together, and it's hard to grow the seagrass they eat in an aquarium. Only one orphaned calf has ever been successfully raised in captivity.

Worldwide, only four dugongs are kept in captivity. A female from the Philippines lives at Toba Aquarium in Toba, Mie, Japan. A male also lived there until he died in 2011. The second lives in Sea World Indonesia. It was rescued from a fisherman's net and treated. The last two, a male and a female, are at Sydney Aquarium. They have been there since they were young.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Dugongo para niños

In Spanish: Dugongo para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |