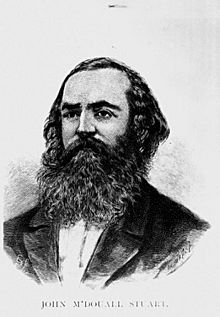

John McDouall Stuart facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John McDouall Stuart

|

|

|---|---|

John McDouall Stuart

|

|

| Born | 7 September 1815 |

| Died | 5 June 1866 (aged 50) |

| Occupation | Explorer of Australia, Surveyor, Grazier. |

John McDouall Stuart (born September 7, 1815 – died June 5, 1866) was one of Australia's most famous explorers. He led six important trips into the center and north of Australia. He spent more time exploring the Australian bush than almost anyone else.

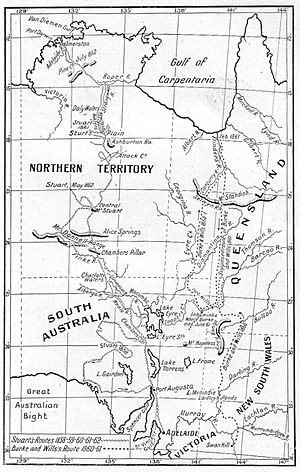

On his journeys, Stuart always managed to go further north. He found important water sources that helped him on his final, long trip. In 1862, he became the first European to cross the entire Australian continent from Adelaide, South Australia, to Van Diemen Gulf in the Northern Territory, and then return.

Exploring Australia made Stuart very sick with diseases like scurvy and beriberi. He pushed himself to his limits. Each trip left him weaker. By the end of his last journey, he was so sick he had to be carried back. Stuart's discoveries helped open up the land for sheep and cattle farming. His route was later used to build the Australian Overland Telegraph Line. This line connected Adelaide to Darwin, which then linked to an undersea cable from Java. For the first time, Australians could communicate quickly with the rest of the world.

Stuart's personal rewards were small. He received some land and a small salary from his employers. He died in England at age 50, not a rich man.

Contents

- Early Life and Education

- Starting His Australian Adventures

- The Central Australian Expedition (1844)

- Stuart's First Solo Expedition (1858)

- Stuart's Second Expedition (1859)

- Third Expedition (1859)

- Fourth Expedition (1860)

- Fifth Expedition (1861)

- Sixth and Final Expedition (1861–62)

- Later Life and Legacy

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life and Education

John McDouall Stuart was born on September 7, 1815, in Dysart, Fife, Scotland. His father, William Stuart, was a captain in the British Army. John was the sixth of nine children.

When he was ten years old, both his parents died. The children were separated and went to live with different relatives. Stuart went to the Scottish Naval and Military Academy in Edinburgh. There, he studied to become an engineer and surveyor.

Starting His Australian Adventures

In 1839, Stuart moved to Adelaide, South Australia. He started working as a surveyor. Adelaide was a very new city, only two years old, and mostly made of tents. The government needed maps to sell or lease land.

Stuart spent three years working on the edges of the settled areas. He measured land and divided it into farm blocks. During this time, he learned important skills for living and traveling in the Australian bush. When the South Australian economy faced a difficult time, Stuart lost his job.

The Central Australian Expedition (1844)

In August 1844, Stuart joined Charles Sturt's Central Australian Expedition. Sturt believed there was a large inland sea in the middle of Australia. He even brought a big boat with him! Stuart joined as a draftsman, which meant he would draw the maps. He was paid one pound a week and given food.

Stuart and James Poole, who was second in command, often went ahead of the main group to find water. The main group could only move as fast as their sheep. Stuart and Poole found water at Depot Glen, near where Milparinka is today.

The weather was very hot and dry. The group got stuck at this waterhole for seven months. Stuart led small groups to look for water to the north, west, and east, but they found none. Stuart was left in charge of the main group at Depot Glen. It was so hot that they dug an underground room to stay cool.

All the men became sick with scurvy. This disease is caused by not having enough fresh fruit and vegetables. Their gums became soft, their teeth fell out, they had headaches, nosebleeds, and their skin turned black.

When Poole died, Stuart became second in command. He also took over all the surveying and mapping because Sturt could not see well. When it finally rained, the group tried to go north again. But they were stopped by the sand dunes of the Simpson Desert. They turned south and went back to the Darling River. Stuart took over as leader when Sturt became blind and too ill to continue. They arrived back in Adelaide after six weeks of hard travel. Sturt had to be carried in a cart, and Stuart, who was weak from scurvy and beriberi, looked like a skeleton.

It took Stuart almost a year to get better from this expedition. In 1849, he moved near Port Lincoln on the Eyre Peninsula and worked on a farm. He soon found work surveying in the area. There, he met William Finke and James Chambers. Finke and Chambers were rich men. They paid Stuart to explore for them, hoping he would find new farm lands, water, and minerals like gold and copper.

Stuart's First Solo Expedition (1858)

Stuart learned from his trip with Sturt that large groups moved too slowly in the dry Australian lands. He believed a small group would be more successful. Finke paid him to find out if the land north of Lake Torrens was good for sheep.

On this first solo trip, Stuart went with two men, Forster and an unnamed Aboriginal youth. They took six horses, enough food for six weeks, a watch, and a compass. In May 1858, they traveled through settled areas until they reached Oratunga Station. This was one of the most remote farms in South Australia, near the town of Blinman. From there, they went northwest and found a permanent water hole. Stuart named it Chambers Creek, but it is now called Stuart Creek.

The land was very dry. They could only find water in Aboriginal wells. The stony ground hurt the horses' feet. By the end of July, they reached the area where Coober Pedy is today. Their horses were tired, and they were running out of food. Stuart decided to change direction and try to reach the coast near Fowlers Bay. The Aboriginal youth would not go any further because he was afraid of other Aboriginal groups in that area. He went back. Stuart described the land as "...dreary, dismal, dreadful desert."

Stuart and Forster reached the coast at Denial Bay in August 1858. By September 11, they were back in settled farm lands. They had traveled about 2,400 km (1,491 mi) in four months. Stuart gave his diary and maps to the South Australian government. As a reward, Stuart was given the lease to 1,000 square miles of land at Chambers Creek.

Stuart's Second Expedition (1859)

The official South Australian government explorer, Benjamin Herschel Babbage, used Stuart's maps and went to Chambers Creek. He reported that Stuart's map showed the creek 46 km (29 mi) too far north. So, Stuart went back to Chambers Creek to survey the area again. James Chambers and William Finke paid for this trip. They knew how important reliable water supplies were beyond the salt lakes.

Stuart left Oratunga Station on April 2, 1859, with a small group of three men and 14 horses. The men included David Herrgott, a Bavarian naturalist and artist, and Louis Müller, a stockman and botanist. Both Herrgott and Müller had been gold miners in Victoria, so they knew how to look for gold. They did not carry much equipment, only a blanket to sleep with, but no tents. Their food was just flour, dried beef (jerky), tea, sugar, and tobacco. This time, Stuart took more than just his watch and compass; he had a sextant, an Astronomical Almanac, and a telescope.

Stuart took a different path to Chambers Creek. He went through a gap between the salt lakes that Major Peter Warburton had found earlier that year. Herrgott discovered a group of 12 artesian springs. Stuart named them after Herrgott. This place later became the settlement of Herggott Springs. During World War I, the name was changed because of strong anti-German feelings in Australia. The town is now called Marree, after the Aboriginal word for possum.

These springs were "mound springs." Over thousands of years, the salt in the water had formed small hills, and the water came out of them like water from a volcano. Some mounds were over 50 m (164 ft) high. They were very important because they provided reliable water for people and animals traveling north to Chambers Creek.

After surveying Chambers Creek again, Stuart explored the area northwest of it. They found more mound springs, which Stuart named Elizabeth Springs after one of Chamber's daughters. They kept going northwest and looked for gold in the Davenport Range. They found more springs, which they named the Spring of Hope. They continued and found even more springs, which Stuart named Freeling Springs, after Major Freeling, a South Australian politician.

By the time they passed the area where Oodnadatta is now, both the men and horses were suffering from lack of water and proper food. The horses' shoes had worn out on the rocks around the Davenport Range. On June 12, 1859, Stuart turned back. They rode south to Port Augusta and then took a boat back to Adelaide.

Third Expedition (1859)

The South Australian government offered a prize of £2,000 to the first person to cross Australia from south to north. They hoped this would be the route for the Australian Overland Telegraph Line, connecting Australia to a line coming from Europe. Stuart and Chambers' plans for the trip were not accepted by the government. Instead, the government sent Alexander Tolmer to lead the trip, but his expedition failed to leave the settled areas.

In August 1859, just one month after his last trip, Stuart went back to Chambers Creek to do more surveying for Chambers. With William Darton Kekwick and two other men, they took 12 horses and explored the west side of Lake Eyre. Chambers and Stuart thought the lake might hold water. But Stuart found only mud after walking several kilometers into the dry salt lake.

He discovered another artesian mound spring, more than 30 m (98 ft) high, which he named William Springs, after one of Chamber's sons. He then headed for the Spring of Hope. He found grasslands and eventually set up a base at Freeling Springs. He explored much of the area around it, hoping to find gold. On January 6, 1859, with food supplies running low and two men refusing to go further, Stuart returned home again.

Fourth Expedition (1860)

There was a lot of public interest in crossing Australia. In Melbourne, the biggest exploring expedition in Australian history was being planned for the crossing. This became known as the Burke and Wills expedition, named after its leaders, Robert O'Hara Burke and William John Wills. Stuart knew he could travel further and faster with a small group. In March 1860, with Kekwick, Benjamin Head, and 13 horses, Stuart left Chambers Creek and headed north.

They were the first Europeans to enter central Australia. They discovered the Finke River, the MacDonnell Ranges, and the strange rock formation Stuart called Chambers Pillar. On April 23, Stuart calculated that they were at the very center of Australia. He named a small hill nearby Mount Sturt, after Charles Sturt. Stuart and Kekwick climbed the hill and raised the British flag. The name was later changed to Central Mount Stuart. From here, Stuart tried to go northwest to reach the Victoria River. This took them into the Tanami Desert, but they could not find water and had to turn back.

They continued north, past the area where Tennant Creek is now. On June 26, they reached a creek, now called Attack Creek, about 2,400 km (1,491 mi) north of Adelaide. A large group of Warramunga Aboriginal people attacked the explorers. The Warramunga threw boomerangs and set fire to the grass. Stuart and his men fired their guns, but Stuart's diary does not say if anyone was killed or hurt. The men quickly left the creek and went south.

Stuart decided they could not go any further north. They were running out of food, water was scarce, and the horses were in poor condition. The journey back was very difficult. Stuart could only ride for a few hours a day; on one day, he just dug a hole in the sand and curled up in it. Their clothes were torn rags, and their bodies were covered in bruises from scurvy.

The explorers made their way back to Adelaide as Burke and Wills were starting their journey north from Melbourne. Stuart was treated as a hero when he arrived in Adelaide. In 1859, the Royal Geographical Society in London gave him a gold watch. This was given to explorer Count Paul Strzelecki to take back to Australia.

The cost of Stuart's exploring had been paid by Chambers. Because of this, Stuart would not make his journals and maps public. This led to claims that Stuart had not really traveled that far north and was lying about his discoveries. In Victoria, some even said Stuart had been hiding in a cellar in Adelaide!

Fifth Expedition (1861)

The public and newspapers began talking about a race across Australia. Could Stuart, who was experienced and moved quickly, beat the better-equipped but very slow Burke and Wills expedition? After their failures with Babbage and Tolmer's trips, the South Australian government now believed Stuart would succeed if he had enough support. They gave £2,500 to set up another expedition and provided ten armed men to protect Stuart from any more attacks by Aboriginal people.

On January 1, 1861, Stuart, with a group of 12 men and 49 horses, set off from Chambers Creek. The hot weather made it hard to find water, and many waterholes from his earlier trips were dry. In February, Stuart sent back two men with five horses. They reached the northern border of South Australia around the same time that Burke and Wills reached the Gulf of Carpentaria. Stuart was able to travel 240 km (149 mi) north of Attack Creek. There, he found a large waterhole he called Glandfield Lagoon, after the mayor of Adelaide.

Chambers later changed the name on Stuart's maps to Newcastle Waters, after the Duke of Newcastle, a British politician. From here, Stuart again looked for a way to go northwest to the Victoria River, but he could not find water. With food running out, men getting sick, and horses in poor condition, Stuart decided to return to Adelaide again. Meanwhile, Burke and Wills had not returned to Cooper Creek and were missing.

Stuart was given the Royal Geographical Society's Patron's Medal for 1861.

Sixth and Final Expedition (1861–62)

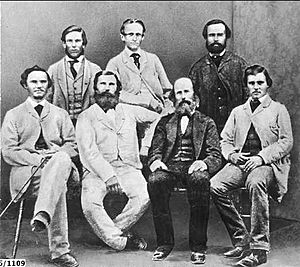

Stuart began his third attempt to cross Australia on October 25, 1861. This expedition was called the Great Northern Exploring Expedition. The group included John McDouall Stuart, William Darton Kekwick, Francis William Thring, William Patrick Auld, Stephen King Jnr., John William Billiatt, James Frew Jnr., Heath Nash, John Woodforde, John McGorrery, and Frederick George Waterhouse.

McGorrey was a blacksmith who could fix the shoes on the group's 78 horses. Waterhouse was a naturalist who would keep scientific notes of their discoveries. Stuart was injured when a horse stepped on his right hand, so he stayed behind for a month to recover. During this time, he learned about the deaths of Burke and Wills at Cooper Creek.

The group left Chambers Creek on January 8, 1862. They moved fast, covering between 30 and 50 kilometers a day. This fast pace meant that in the first three weeks, eight horses died, and Woodforde left to go back. Stuart left some supplies behind and cut down the amount of food each man was allowed to eat. At Mount Hay in central Australia, they were again attacked by Aboriginal warriors. But they were no match for the group's guns, and several warriors may have been killed.

They reached Newcastle Waters in three months and then rested for a week. Stuart spent the next five weeks searching for water. He finally found a series of waterholes, creeks, and rivers. This meant the whole group could continue north. He gave up trying to reach the Victoria River. When they reached the Roper River, which Ludwig Leichhardt had discovered in 1845, Stuart knew he could easily go west to the Gulf of Carpentaria. Instead, he chose to continue north.

They crossed Arnhem Land and made their way along the edge of what is now Kakadu National Park. He followed the Adelaide River, but when the ground became too soft and muddy, they went further north to the Mary River and finally reached the sea.

They arrived at Van Diemen's Gulf on July 24, 1862. On a tall tree branch, they raised a Union Jack flag with Stuart's name embroidered on it. This flag had been made by Chamber's daughter, Elizabeth. Wood from the tree, which has since been destroyed, is now in the collection of the Royal Geographical Society of South Australia.

The group then had to travel 3,400 km (2,113 mi) back to Adelaide. Food was becoming scarce, and the hot weather meant there was little water. Many horses died, and Stuart was again forced to leave equipment behind. Waterhouse had to leave all his carefully collected plants and animals. The men were very hungry and even shot and ate dingos.

Stuart was in poor health and became blind. He could not speak for several days, and the men thought he was going to die. He was unable to ride his horse. So, they made a bed with long poles and blankets that could be carried between two horses. Stuart was carried 960 km (597 mi) this way. After crossing the MacDonnell Ranges, they found that rain had fallen, and there was plenty of grass.

On reaching the settled areas, Stuart learned that his friend and partner, James Chambers, had died. He left Kekwick in charge of the group and went ahead with Auld. They took the train at Kapunda and arrived in Adelaide on December 17, 1862.

Stuart and his group received a special welcome in Adelaide on January 16, 1863. They dressed in their old clothes and rode into the city as heroes. This was also the day that Burke and Wills were buried in Melbourne after their expedition failed.

Later Life and Legacy

After his sixth trip, Stuart was in poor health. He was almost blind and had a crippled right hand. With Chambers dead, he no longer had a job. The government tried not to pay him the £2,000 reward, saying they had paid for the expedition's costs. After public pressure, they gave in, but they invested the money and only gave Stuart a small amount each year. The government then wanted £500 for the lease of the land they had given him at Chambers Creek. Stuart sold it to James Chambers' brother, John Chambers, for only £200, losing money on the deal.

He decided to return to Great Britain in April 1864. He lived with his sister Mary in Glasgow, Scotland. The Royal Geographical Society asked the South Australian government for a pension for Stuart, but they said he had been rewarded enough with land grants.

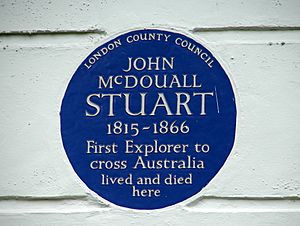

Stuart suffered from dementia, and it is possible he also had tuberculosis. He died in London on June 5, 1866, from a stroke. He was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery. Only seven people attended his funeral: four relatives, two members of the Royal Geographical Society, and Alexander Hay, a South Australian farmer who was in London at the time. His grave was damaged in World War II but was repaired in 2010 by the Stuart Society and the Royal Geographical Society of South Australia.

The Australian Overland Telegraph Line was built along the route Stuart discovered. Using his notes, workers easily found water supplies and trees for the poles. The accuracy of his maps made building the line much easier. Stuart's journey is remembered in the Stuart Highway, one of Australia's major roads that connects Port Augusta to Darwin. It follows much of the same route he discovered. In June 1904, a statue of Stuart was put up in Adelaide. The Royal Geographical Society of South Australia has a wooden chair and table made by Stuart in 1854.

Images for kids

-

Birthplace of Stuart in Dysart, Scotland

See also

In Spanish: John McDouall Stuart para niños

In Spanish: John McDouall Stuart para niños

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |