Nellie Melba facts for kids

Dame Nellie Melba (born Helen Porter Mitchell; 19 May 1861 – 23 February 1931) was a famous Australian opera singer. She was a type of singer called a lyric coloratura soprano, known for her clear, high voice. Nellie Melba became one of the most well-known singers of her time. She was the first Australian to become famous around the world as a classical musician. She chose the stage name "Melba" from her hometown, Melbourne.

Melba studied singing in Melbourne and had some success there. After a short marriage, she moved to Europe to start a singing career. She didn't find work in London at first in 1886. So, she studied in Paris and quickly became very successful there and in Brussels. When she returned to London in 1888, she became the main lyric soprano at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. She also found more success in Paris, other parts of Europe, and later in New York at the Metropolitan Opera, starting in 1893.

Melba sang a small number of roles, about 25 in her whole career. She was best known for about ten of these. She was famous for singing in French and Italian operas. During the First World War, Melba helped raise a lot of money for charities. She often visited Australia in the 20th century, performing in operas and concerts. She also had a house built near Melbourne. Melba taught singing at the Melbourne Conservatorium. She kept singing until close to the end of her life. Her death in Australia was big news around the world. Her funeral was a very important national event. Her picture is on the Australian $100 note.

Contents

Life and Career of Nellie Melba

Early Life and Music Studies

Nellie Melba was born in Richmond, Victoria. She was the oldest of seven children. Her father, David Mitchell, was a successful builder who came from Scotland. Melba started playing the piano and singing in public when she was about six years old. She went to a local boarding school and then to the Presbyterian Ladies' College.

She learned singing from Mary Ellen Christian and Pietro Cecchi. He was an Italian tenor and a respected teacher in Melbourne. As a teenager, Melba kept performing in concerts around Melbourne. She also played the organ at church. Her father supported her music studies. However, he did not want her to become a professional singer. Melba's mother died suddenly in 1881.

Melba's father moved the family to Mackay, Queensland. There, he built a new sugar mill. Melba quickly became popular in Mackay for her singing and piano playing. In 1882, she married Charles Nesbitt Frederick Armstrong in Brisbane. They had one son, George, born in 1883. The marriage did not last long, and they separated after about a year. Melba returned to Melbourne to become a professional singer. She began performing professionally in concerts in 1884.

Starting Her Opera Career

After her success in Australia, Melba went to London in 1886. She hoped to find singing opportunities there. Her first performance in London did not make a big impression. She tried to get work from famous people like Sir Arthur Sullivan, but she was not successful. Then, she went to Paris to study with Mathilde Marchesi, a top singing teacher. Marchesi immediately saw Melba's great talent. She famously said, "I have a star at last!"

Melba improved so quickly that she sang a difficult piece from the opera Hamlet in December of that year. The composer was there and was very impressed. After less than a year with Marchesi, a manager named Maurice Strakosch offered her a ten-year contract. But then she got a much better offer from an opera house in Brussels. Strakosch would not let her go. Luckily, Strakosch died suddenly, which solved the problem.

Melba made her first opera performance just four days later. She sang the role of Gilda in Rigoletto in Brussels on 12 October 1887. A critic called it "an instant triumph." A few nights later, she had equal success as Violetta in La traviata. It was at this time that she chose her stage name, "Melba." Her teacher, Marchesi, suggested it. It was a shorter version of her home city, Melbourne.

Success in London, Paris, and New York

Melba first performed at Covent Garden in London in May 1888. She sang the main role in Lucia di Lammermoor. The audience liked her, but they were not overly excited. One newspaper said she was a good singer but lacked the special charm of a great opera star. She was upset when the manager offered her only a small role for the next season. She left England, vowing not to return.

The next year, she sang at the Opéra in Paris. She performed as Ophélie in Hamlet. The Times newspaper called it a "brilliant success." They said her voice was very flexible and her acting was expressive. Melba had a strong supporter in London, Lady de Grey. Lady de Grey was very influential at Covent Garden. Melba was convinced to return. The manager cast her in Roméo et Juliette in June 1889. She later said, "I date my success in London quite distinctly from the great night of 15 June 1889."

After this, she went back to Paris. She sang roles like Ophélie, Lucia, Gilda, Marguerite, and Juliette. Even though her French pronunciation was not perfect, the composer Delibes said he didn't care. He just wanted her to sing. In the early 1890s, Melba performed in major European opera houses. These included Milan, Berlin, and Vienna.

Melba sang the role of Nedda in Pagliacci at Covent Garden in 1893. The composer was there and said she performed the role better than anyone before. In December of that year, Melba sang at the Metropolitan Opera in New York for the first time. Like her London debut, she sang Lucia di Lammermoor. It was not a huge triumph. The New York Times praised her voice. They called it "one of the loveliest voices that ever issued from a human throat." However, the opera itself was not popular then, so few people attended.

Her performance in Roméo et Juliette later that season was a great success. This made her the leading opera star of her time. Melba sang many different roles at Covent Garden from the 1890s. Most were for a lyric soprano voice. She also sang some heavier roles. Her Italian roles included Gilda in Rigoletto and Mimì in La bohème. In French operas, she sang Juliette in Roméo et Juliette and Marguerite in Faust.

Melba sometimes sang Micaëla in Carmen, which is a supporting role. She said she didn't understand why a main singer shouldn't sing smaller parts. She hated "artistic snobbery." She was kind to other singers who did not compete with her. However, she was very critical of other lyric sopranos. Melba was not known for singing Wagner's operas. She did sing Elsa in Lohengrin and Elisabeth in Tannhäuser sometimes. Critics praised her skill but sometimes found her acting artificial. Her most frequent role in New York was Marguerite in Gounod's Faust. She had studied this role with the composer himself. Melba never sang in Mozart's operas. Her entire career included only about 25 roles. About 10 of these are the ones she is best remembered for.

Melba's marriage ended when her husband divorced her in Texas in 1900.

The Twentieth Century and Later Life

By the early 1900s, Melba was a top star in Britain and America. She made her first trip back to Australia in 1902–03 for a concert tour. She also toured New Zealand. She earned a lot of money from these tours. She returned to Australia for four more tours during her career. In Britain, Melba strongly supported Puccini's opera La bohème. She first sang the role of Mimì in 1899. She had studied it with the composer. She pushed for more performances of the opera. Covent Garden management did not like this "new and common opera." But the public loved it. In 1902, Enrico Caruso joined her for many performances of La bohème at Covent Garden.

Melba performed 26 times at the Royal Albert Hall in London. This was between 1898 and 1926. She called Covent Garden "my artistic home." However, she sang there less often in the 20th century. One reason was that she did not get along with Sir Thomas Beecham. He managed the opera house for much of that time. She said, "I dislike Beecham and his methods." He thought she lacked "genuine spiritual refinement." Another reason was the rise of Luisa Tetrazzini. She was a soprano ten years younger than Melba. Tetrazzini became very successful in London and New York. A third reason was Melba's decision to spend more time in Australia. In 1909, she went on a "sentimental tour" of Australia. She traveled 10,000 miles (16,000 km) and visited many small towns. In 1911, she performed in an opera season with the J. C. Williamson company.

In 1909, Melba bought land in Coldstream, near Melbourne. In 1912, she built a home there. She called it Coombe Cottage. She also started a music school in Richmond. Later, this school joined the Melbourne Conservatorium. Melba was in Australia when the First World War began. She worked hard to raise money for war charities. She raised £100,000. Because of this, she was given the title Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in 1918. This was for her "services in organising patriotic work."

After the war, Melba made a grand return to the Royal Opera House. She performed in La bohème, conducted by Beecham. This performance reopened the opera house after four years. The Times newspaper wrote that no season at Covent Garden had ever started with such excitement. However, in her many concerts, her song choices were seen as too simple and predictable.

In 1922, Melba returned to Australia. She sang in very popular "Concerts for the People" in Melbourne and Sydney. Tickets were cheap, and 70,000 people attended. In 1926, she made her farewell performance at Covent Garden. She sang parts from Roméo et Juliette, Otello, and La bohème. She is well-remembered in Australia for her many "farewell" appearances. These included stage shows in the mid-1920s. She also gave concerts in Sydney in 1928 and Melbourne in 1928. This led to the Australian saying, "more farewells than Dame Nellie Melba."

In 1929, she went to Europe for the last time. She then visited Egypt. There, she caught a fever that she never fully recovered from. Her last performance was in London at a charity concert in June 1930. She returned to Australia but died in Sydney in 1931. She was 69 years old. She died from an infection that started after facial surgery in Europe. She had a grand funeral at Scots' Church in Melbourne. Her father had built this church. As a teenager, she had sung in its choir. The funeral procession was over a kilometer long. Her death was front-page news in many countries. Billboards simply said "Melba is dead." Part of the event was filmed. Melba was buried in Lilydale, near Coldstream. Her headstone has the words from Mimì in La bohème: "Addio, senza rancor" (Farewell, without bitterness).

Teacher and Supporter

Even though some people did not like Melba, she helped many younger singers. She taught for many years at the Conservatorium in Melbourne. She was always looking for a "new Melba." She wrote a book about her teaching methods. These were based on what she learned from Marchesi.

Other singers also benefited from Melba's support. She shared her special singing techniques with a young Gertrude Johnson. In 1924, Melba brought the new star Toti Dal Monte to Australia. Dal Monte was famous in Milan and Paris but not yet in England or the United States. Melba made her a main singer in the Melba-Williamson Grand Opera Company. After singing with another Australian soprano, Florence Austral, Melba praised her highly. She called Austral "one of the wonder-voices of the world." She also said the American contralto Louise Homer had "the world's most beautiful voice."

Melba also gave money to the Australian painter Hugh Ramsay. He was living in poverty in Paris. She also helped him meet important people in the art world. The Australian baritone John Brownlee and tenor Browning Mummery were also helped by her. They both sang with her in her 1926 Covent Garden farewell performance. Brownlee also sang with her on two of her last recordings.

Recordings and Radio Broadcasts

Melba made her first recordings around 1895. These were on cylinders at the Bettini Phonograph Lab in New York. A reporter was very impressed. He said the phonograph reproduced her voice wonderfully, especially the high notes. Melba herself was not as impressed. She said, "Never again," after hearing the "scratching, screeching result." These recordings were never released to the public. It is thought that Melba ordered them to be destroyed. She did not go into a recording studio again for eight years.

You can hear Melba singing on some Mapleson Cylinders. These were early attempts to record live performances. They were made by the Metropolitan Opera House librarian, Lionel Mapleson. These recordings are often not very clear. However, they show some of the quality of Melba's young voice. This quality is sometimes missing from her later commercial recordings.

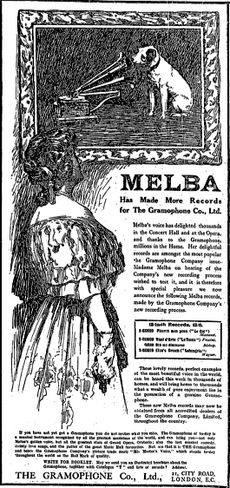

Melba made many gramophone records of her voice. She recorded in England and America between 1904 and 1926. She was in her 40s when she started. Most of these recordings are opera songs, duets, and other pieces. Many have been re-released on CD. The sound quality of these early recordings is not perfect. They do not capture all the richness of her voice. But they still show that Melba had a very pure voice. She could sing difficult parts easily. She also sang smoothly and in perfect tune. Melba had perfect pitch. One critic said she only made two small mistakes in pitch in all her London recordings.

Melba's farewell performance at Covent Garden on 8 June 1926 was recorded and broadcast. The show included parts from Roméo et Juliette, Otello, and La bohème. At the end, Lord Stanley of Alderley gave a speech. Melba then gave an emotional farewell speech. Eleven records were made from this event. Only three were released at the time. The full set, including the speeches, was released later in 1976.

Many of Melba's recordings were made at "French Pitch." This was a slightly different musical tuning than what is common today. This, along with early recording problems, means playing her recordings at the correct speed and pitch can be tricky.

On 15 June 1920, Melba was heard in a special radio broadcast. It was from Guglielmo Marconi's factory in Chelmsford. She sang two opera songs and her famous trill. She was the first international artist to sing live on radio. People across the country heard her. The broadcast was even heard as far away as New York. Listeners sometimes only heard scratches. Later radio broadcasts included her Covent Garden farewell. There was also an "Empire Broadcast" in 1927. This was heard across the British Empire.

Honors and Legacy

Melba was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1918. This was for her charity work during World War I. She was one of the first stage performers to receive this honor. In 1927, she was made a Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire. She was the first Australian to appear on the cover of Time magazine in April 1927.

A stained glass window was put in a church in London in 1962 to remember Melba. She is one of only two singers with a marble statue at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. A blue plaque marks the house where she lived in London in 1906. In 2001, she was added to the Victorian Honour Roll of Women. The Melbourne Conservatorium of Music was renamed the Melba Memorial Conservatorium of Music in her honor in 1956. The music hall at the University of Melbourne is called Melba Hall. The suburb of Melba in Canberra is also named after her.

Melba's face is on the Australian $100 note. Her picture has also been on an Australian stamp. Sydney Town Hall has a marble plaque that says "Remember Melba." This was put there during World War II. It honored Melba and her charity work during World War I. A tunnel on Melbourne's EastLink freeway is named after her. Streets named after her include Melba Avenue in San Francisco. There is also Avenue Nellie Melba in Brussels.

Melba's home in Marian, Queensland, has been moved and restored. It is now called Melba House. It is a museum about Melba and a visitor center. Her home Coombe Cottage in Coldstream, Victoria, is now owned by her granddaughter's sons. The house was designed by John Harry Grainger. He was the father of composer Percy Grainger and a friend of Melba's father.

Melba's name is linked to four foods. These were all created for her by the French chef Auguste Escoffier:

- Peach Melba, a dessert with peaches, raspberry sauce, and vanilla ice cream.

- Melba sauce, a sweet sauce made from raspberries and red currants.

- Melba toast, a thin, crisp, dry toast.

- Melba Garniture, chicken, truffles, and mushrooms stuffed into tomatoes with a special sauce.

Melba planted a type of poplar tree in the Melbourne Botanic Gardens in 1903. It is now known as "Melba's poplar." On 19 May 2011, Google celebrated her 150th birthday with a special Google Doodle.

Books and Films About Melba

Melba's autobiography, Melodies and Memories, was published in 1925. Her secretary, Beverley Nichols, mostly wrote it for her. Nichols later said Melba did not help much with the writing. Other books about her life include those by Agnes G. Murphy (1909), John Hetherington (1967), Thérèse Radic (1986), and Ann Blainey (2009).

A novel called Evensong by Nichols (1932) was based on parts of Melba's life. It showed her in a not-so-flattering way. A 1934 movie based on Evensong was banned in Australia for a while. Melba also appears in the 1946 novel Lucinda Brayford. She is described as having the "loveliest voice in the world" at a garden party.

In 1946–1947, a popular radio series about Melba was made. Glenda Raymond played her. In 1953, a movie called Melba was released. The opera singer Patrice Munsel played Melba. In 1987, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation made a mini-series called Melba. Linda Cropper acted as Melba, with Yvonne Kenny providing the singing voice. Kiri Te Kanawa played Melba in an episode of the British TV show Downton Abbey in 2013. She performed at the abbey as a guest.

See also

In Spanish: Nellie Melba para niños

In Spanish: Nellie Melba para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |