History of Singapore facts for kids

The modern history of Singapore began in the early 1800s. However, there is proof that a busy trading town existed on the island much earlier, in the 1300s. The last ruler of the Kingdom of Singapura, Parameswara, was forced out by the Majapahit or Siamese empires. He then went on to found Malacca. Singapore later came under the rule of the Malacca Sultanate and then the Johor Sultanate.

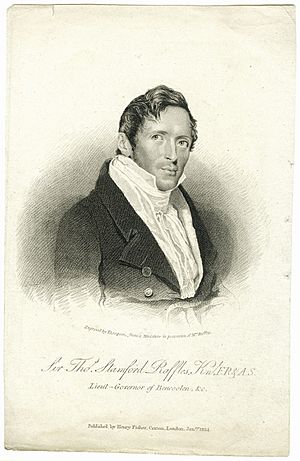

In 1819, a British leader named Stamford Raffles made a deal. This deal allowed the British to set up a trading port on the island. This led to Singapore becoming a British colony in 1867. Singapore grew important because it was in a great location at the tip of the Malay Peninsula, between the Pacific and Indian Oceans. It also had a safe natural harbour and was a free port, meaning no taxes on trade.

During World War II, the Japanese Empire took over Singapore from 1942 to 1945. After Japan surrendered, Singapore went back to British control. It slowly gained more self-rule. In 1963, Singapore joined the Federation of Malaya to form Malaysia. But there were problems like social unrest, racial tensions, and political disagreements. These issues led to Singapore being asked to leave Malaysia. Singapore became an independent country on 9 August 1965.

By the 1990s, Singapore had become one of the richest countries in the world. It had a very developed free market economy and strong connections for international trade. Today, it has one of the highest incomes per person in Asia and ranks high globally for human development.

Contents

Ancient Singapore's Early Days

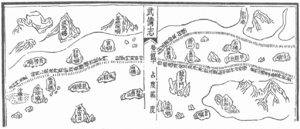

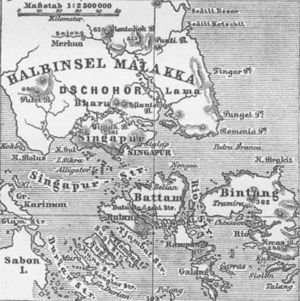

An ancient Greek-Roman astronomer named Ptolemy (who lived from 90 to 168 AD) wrote about a place called Sabana. This place was at the tip of the Malay Peninsula. The first written record of Singapore might be from a Chinese book in the 200s AD. It described an island called Pu Luo Chung. This name might be linked to the Malay name "Pulau Ujong", which means "island at the end" of the Malay Peninsula.

In 1025 AD, Rajendra Chola I from the Chola Empire sailed across the Indian Ocean. He attacked parts of the Srivijayan empire in Malaysia and Indonesia. It's believed that Chola forces controlled Temasek (which is now Singapore) for about twenty years. While Temasek isn't in Chola records, a story about a Raja Chulan (thought to be Rajendra Chola) and Temasek is in the Malay Annals.

The Nagarakretagama, a poem from Java written in 1365, mentioned a settlement on the island called Tumasik. This name probably means "Sea Town" or "Sea Port." The name Temasek also appears in the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals). This book tells a story about a prince from Palembang, Sri Tri Buana (also known as Sang Nila Utama), who founded Temasek in the 1200s. The story says Sri Tri Buana was hunting on Temasek and saw a strange animal, which he thought was a lion. He took this as a good sign and founded a settlement called Singapura. In Sanskrit, Singapura means "Lion City." However, experts say the real origin of the name Singapura is not fully clear.

In 1320, the Mongol Empire sent a trade mission to a place called Long Ya Men. This place is thought to be Keppel Harbour in southern Singapore. A Chinese traveler named Wang Dayuan visited the island around 1330. He described Long Ya Men as one of two main settlements in Dan Ma Xi (from Malay Temasek). The other was Ban Zu, which is believed to be Fort Canning Hill today. Recent digs at Fort Canning show that Singapore was an important settlement in the 1300s. Wang mentioned that local people (likely the Orang Laut) and Chinese residents lived together in Long Ya Men. Singapore is one of the oldest places outside China where a Chinese community is known to have lived.

By the 1300s, the Srivijaya empire was weakening. Singapore became caught in a fight between Siam (now Thailand) and the Majapahit Empire from Java. Both wanted control over the Malay Peninsula. According to the Malay Annals, Singapore was defeated in a Majapahit attack. The last king, Sultan Iskandar Shah, ruled the island for some years. He was then forced to go to Melaka, where he founded the Sultanate of Malacca. However, Portuguese records say that Temasek was controlled by Siam. Its ruler was killed by Parameswara (thought to be Sultan Iskandar Shah). Parameswara was then driven to Malacca by either the Siamese or the Majapahit. Modern archaeological findings suggest that the settlement on Fort Canning was left empty around this time. But a small trading post continued in Singapore for a while.

The Malacca Sultanate took control of the island, and Singapore became part of it. But by the early 1500s, when the Portuguese arrived, Singapura was already "great ruins." In 1511, the Portuguese captured Malacca. The Sultan of Malacca escaped south and started the Johor Sultanate. Singapore then became part of this new sultanate. In 1613, the Portuguese destroyed the settlement in Singapore. The island then became forgotten for the next two hundred years.

1819: British Colony of Singapore

Between the 1500s and 1800s, European powers slowly took over the Malay Archipelago. The Portuguese arrived in Malacca in 1509. The Dutch then challenged their power in the 1600s. The Dutch gained control of most ports and had a monopoly on spice trade. Other powers, like the British, had only a small presence.

In 1818, Sir Stamford Raffles became the Lieutenant Governor of the British colony at Bencoolen. He wanted Great Britain to become the main power in the region. The trade route between China and British India was very important and passed through the archipelago. The Dutch were making it hard for British trade by blocking them from ports or charging high taxes. Raffles wanted to challenge the Dutch by setting up a new port along the Straits of Malacca. This was the main shipping lane for trade between India and China. The British only had ports in Penang and Bencoolen, which were not ideal. Penang was too far to protect traders from pirates, and Bencoolen was not on the main trade route.

Raffles needed a port that was in a good spot along the main trade route. He convinced Lord Hastings, the Governor-General of India, to pay for an expedition. This trip was to find a new British base in the region.

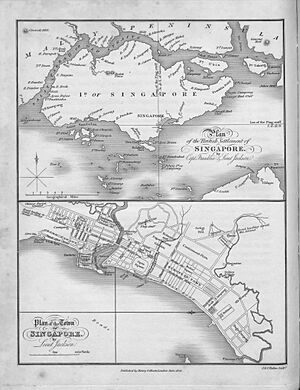

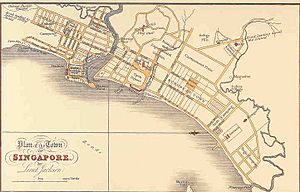

Raffles arrived in Singapore on 28 January 1819. He quickly saw that the island was perfect for a new port. It was at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, near the Straits of Malacca. It had a natural deep harbour, fresh water, and wood for ship repairs. It was also right on the main trade route between India and China.

Raffles found a small Malay village at the mouth of the Singapore River. It had about 150 people, mostly Malays and some Chinese. The village was led by the Temenggong and Tengku Abdul Rahman. The island was officially ruled by the Sultan of Johor. But the Sultanate was weak and divided. Tengku Abdul Rahman and his officials were loyal to Tengku Rahman's older brother, Tengku Long, who was living in exile in Riau.

With the Temenggong's help, Raffles secretly brought Tengku Long back to Singapore. Raffles offered to recognize Tengku Long as the rightful Sultan of Johor, giving him the title Sultan Hussein. He also promised him a yearly payment of $5,000, and $3,000 to the Temenggong. In return, Sultan Hussein would let the British set up a trading post in Singapore. The Treaty of Singapore was signed on 6 February 1819, and modern Singapore was born.

When Raffles arrived, about 1,000 people lived on the island. Most were local groups who later became part of the Malay community, plus a few Chinese. Singapore's population grew very fast after Raffles arrived. The first count in 1824 showed that 6,505 out of 10,683 people were Malays and Bugis. Many Chinese migrants also came to Singapore just months after it became a British settlement. By 1826, there were more Chinese than Malays. Due to continuous migration from Malaya, China, India, and other parts of Asia, Singapore's population reached almost 100,000 by 1871. More than half of them were Chinese.

Many early Chinese and Indian immigrants came to Singapore to work in plantations and tin mines. Most were men who planned to return home after earning money. However, by the early to mid-1900s, more and more chose to stay permanently. Their descendants now make up most of Singapore's population.

Colonial Singapore (1819–1942)

Early Growth (1819–1826)

Raffles went back to Bencoolen soon after the treaty was signed. He left Major William Farquhar in charge of the new settlement. Farquhar had some artillery and a small group of Indian soldiers. Building a trading port from nothing was a huge challenge. Farquhar's administration didn't have much money. He was not allowed to collect port taxes because Raffles wanted Singapore to be a free port.

Farquhar invited people to settle in Singapore. He placed a British official on St. John's Island to invite passing ships to stop in Singapore. News of the free port spread. Bugis, Peranakan Chinese, and Arab traders came to the island. They wanted to avoid Dutch trade rules. In its first year, 1819, $400,000 worth of trade passed through Singapore. By 1821, the island's population was about 5,000, and trade was $8 million. The population reached 10,000 in 1824, with $22 million in trade. Singapore quickly became more important than the older port of Penang.

Raffles returned to Singapore in October 1822. He criticized many of Farquhar's choices, even though Farquhar had successfully led the settlement. For example, to make money, Farquhar had sold licenses for gambling. Raffles was shocked by the disorder and the acceptance of slave trade. He started new rules for the settlement. These included banning slavery, closing gambling places, forbidding weapons, and high taxes on things he saw as bad habits. He also divided Singapore into different areas for different functions and ethnic groups. Today, you can still see parts of this plan in Singapore's ethnic neighbourhoods. William Farquhar was replaced by John Crawfurd, a careful and efficient leader.

On 7 June 1823, John Crawfurd signed another treaty with the Sultan and Temenggong. This treaty gave the British control over most of the island. The Sultan and Temenggong gave up most of their power, including collecting port taxes. In return, they received monthly payments for life ($1500 and $800 respectively). This agreement brought the island under British Law. It also said that Malay customs, traditions, and religion would be respected. In October 1823, Raffles left for Britain and never returned to Singapore. He died in 1826 at age 44. In 1824, Singapore was given to the East India Company forever by the Sultan.

The Straits Settlements (1826–1867)

At first, it was unclear if Singapore would remain a British outpost. The Dutch government protested that Britain was breaking their agreement. But Singapore quickly became an important trading post. So, Britain made its claim on the island stronger. The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 confirmed Singapore as a British possession. It divided the Malay archipelago between the two powers. The area north of the Straits of Malacca, including Singapore, became British. In 1826, the British East India Company grouped Singapore with Penang and Malacca. They formed the Straits Settlements. This group was managed by the British East India Company. In 1830, the Straits Settlements became a subdivision of the Presidency of Bengal in British India.

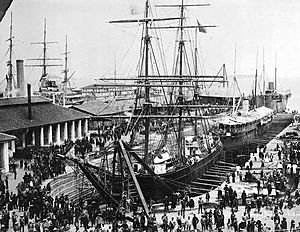

Over the next few decades, Singapore grew into a major port. Its success came from several things. These included the opening of the Chinese market and the use of ocean-going steamships. Shipping goods to Europe became much faster and cheaper after the Suez Canal opened in 1869. Also, rubber and tin production grew in Malaya. The Malay Peninsula wasn't a big part of Singapore's trade until the 1840s. That's when the Chinese started tin-mining in western Malay States and growing gambier-pepper in Johor.

Being a free port gave Singapore a big advantage over other colonial ports like Batavia (now Jakarta) and Manila, where taxes were charged. This attracted many Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Arab traders to Singapore. Steamships needed to refuel often, so they preferred Singapore over Batavia. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 further boosted trade in Singapore. By 1880, over 1.5 million tons of goods passed through Singapore each year. About 80% of this cargo was carried by steamships. The main business was entrepôt trade, which thrived with no taxes and few rules. Many trading companies were set up in Singapore. These were mainly European firms, but also Jewish, Chinese, Arab, Armenian, American, and Indian merchants. There were also many Chinese middlemen who handled most of the trade between European and Asian merchants.

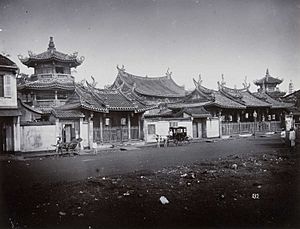

By 1827, Chinese people were the largest ethnic group in Singapore. By 1845, they made up more than half of the population. They included Peranakans, who were descendants of early Chinese settlers. There were also Chinese coolies who came to Singapore to escape poverty in southern China. Their numbers grew because of people fleeing the First Opium War (1839–1842) and Second Opium War (1856–1860). Many arrived in Singapore as poor indentured labourers. Malays were the second largest group until the 1860s. They worked as fishermen, craftsmen, or wage earners, mostly living in kampungs. By 1860, Indians became the second-largest ethnic group. They included unskilled workers, traders, and prisoners sent to do public works like clearing jungles and building roads. British also stationed Indian Sepoy troops in Singapore.

Despite Singapore's growing importance, its government was understaffed and not very effective. It didn't care much about the people's well-being. Leaders were often sent from India and didn't know much about local culture or languages. While the population quadrupled from 1830 to 1867, the number of government workers stayed the same. Most people had no access to public health services. Diseases like cholera and smallpox caused serious health problems, especially in crowded working-class areas. Because the government was ineffective and the population was mostly male, temporary, and uneducated, society was lawless. In 1850, there were only twelve police officers for a city of nearly 60,000 people. Chinese criminal secret societies (like modern-day triads) were very powerful. Some had tens of thousands of members. Fights between rival groups sometimes led to hundreds of deaths. Attempts to stop them had little success.

Straits Settlements Crown Colony (1867–1942)

As Singapore continued to grow, problems in the Straits Settlements government became serious. Singapore's business community started to protest against British Indian rule. The British government agreed to make the Straits Settlements a separate Crown Colony on 1 April 1867. This new colony was ruled by a governor under the Colonial Office in London. An executive council and a legislative council helped the governor. Members of these councils were not elected, but more local representatives were slowly added over the years.

The colonial government took steps to fix Singapore's serious social problems. A Chinese Protectorate was set up in 1877 under Pickering to help the Chinese community. In 1889, Governor Sir Cecil Clementi Smith banned secret societies, forcing them to operate in secret. However, many social problems continued until after the war, including a severe housing shortage and poor health conditions. In 1906, the Tongmenghui, a Chinese revolutionary group led by Sun Yat-sen, opened its Southeast Asian headquarters in Singapore. This group aimed to overthrow the Qing Dynasty in China. Members of the branch included Wong Hong-Kui, Tan Chor Lam, and Teo Eng Hock. Chan Cho-Nam, Cheung Wing-Fook, and Chan Po-Yin started Chong Shing Yit Pao, a Chinese newspaper. This was in response to the growing influence of another newspaper controlled by reformers. The first edition was published on 20 August 1907. The paper closed in 1910 due to money problems. Working with other Cantonese people, Chan, Cheung, and Chan opened the Kai Ming Bookstore in Singapore, which was related to the revolution. For the revolution, Chan Po-Yin raised over 30,000 yuan to buy and ship military equipment from Singapore to China. He also supported people traveling from Singapore to China for revolutionary work. Chinese immigrants in Singapore gave a lot of money to Tongmenghui. This group organized the 1911 Xinhai Revolution that led to the creation of the Republic of China.

World War I (1914–1918) did not greatly affect Singapore. The fighting did not reach Southeast Asia. The only major local military event was a mutiny in 1915. British Muslim Indian soldiers stationed in Singapore revolted. They heard rumors they would be sent to fight the Ottoman Empire. The soldiers killed their officers and some British civilians. Troops from Johor and Burma then stopped the unrest.

After the war, British trade and influence slowly decreased. The importance of the United States and Japan, both in the Pacific, grew. The British government spent a lot of money building a naval base in Singapore. This was meant to deter the growing power of the Japanese Empire. The base was finished in 1939 and cost a huge $500 million. It had the world's largest dry dock at the time, the third-largest floating dock, and enough fuel to support the entire British navy for six months. It was protected by heavy 15-inch naval guns and Royal Air Force planes at Tengah Air Base. Winston Churchill called it the "Gibraltar of the East." But it was a base without a fleet. The British Home Fleet was in Europe. The plan was for it to sail quickly to Singapore if needed. However, when World War II started in 1939, the Fleet was busy defending Britain.

Lieutenant General Sir William George Shedden Dobbie was appointed governor of Singapore and commander of Malaya Command on 8 November 1935. He held this position until just before World War II began in 1939. He developed "The Dobbie Hypothesis" about Singapore's fall. If his warnings had been listened to, Singapore might not have fallen during the war. People in Singapore with German papers, including Jews fleeing the Nazis, were arrested and sent away. The British government called them "citizens of an enemy country."

Battle for Singapore and Japanese Occupation (1942–1945)

In December 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and the east coast of Malaya. This started the Pacific War. Both attacks happened at the same time. Japan wanted to capture Southeast Asia to get its rich natural resources for its military and industries. Singapore, the main Allied base in the region, was an obvious target because of its busy trade and wealth.

British military leaders in Singapore thought the Japanese would attack from the south by sea. They believed the thick Malayan jungle in the north would stop an invasion. They had a plan for an attack on northern Malaya, but it was never fully ready. The military was sure that "Fortress Singapore" could withstand any Japanese attack. This confidence grew when Force Z arrived. This was a group of British warships sent to defend Singapore, including the battleship HMS Prince of Wales and cruiser HMS Repulse. A third large ship, the aircraft carrier HMS Indomitable, was supposed to join them. But it ran aground on the way, leaving the group without air cover.

On 8 December 1941, Japanese forces landed at Kota Bharu in northern Malaya. Just two days after the invasion of Malaya began, Prince of Wales and Repulse were sunk 50 miles off the coast of Kuantan in Pahang. Japanese bombers and torpedo bomber aircraft attacked them. This was the worst British naval defeat of World War II. Allied air support did not arrive in time to protect the two large ships. After this, Singapore and Malaya faced daily air raids. These raids hit civilian buildings like hospitals and shops, causing many deaths and injuries each time.

The Japanese army quickly moved south through the Malay Peninsula. They crushed or bypassed Allied resistance. The Allied forces did not have tanks, as they thought tanks were not suitable for the tropical rainforest. Their soldiers were powerless against the Japanese light tanks. As their resistance failed, the Allied forces had to retreat south towards Singapore. By 31 January 1942, just 55 days after the invasion started, the Japanese had conquered the entire Malay Peninsula. They were ready to attack Singapore.

The causeway connecting Johor and Singapore was blown up by Allied forces to stop the Japanese army. However, the Japanese managed to cross the Straits of Johor in inflatable boats days later. Several battles took place between Allied forces and Singaporean volunteers against the advancing Japanese, such as the Battle of Pasir Panjang. But with most defenses broken and supplies gone, Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival surrendered the Allied forces in Singapore to General Tomoyuki Yamashita of the Imperial Japanese Army. This happened on Chinese New Year, 15 February 1942. About 130,000 Indian, Australian, and British troops became prisoners of war. Many were later sent to Burma, Japan, Korea, or Manchuria to work as forced labourers on "hell ships." The fall of Singapore was the largest surrender of British-led forces in history. Japanese newspapers proudly announced the victory as a turning point in the war.

Singapore was renamed Syonan-to (昭南島 Shōnan-tō, meaning "Bright Southern Island" in Japanese). It was occupied by the Japanese from 1942 to 1945. The Japanese army was very harsh to the local people. Troops, especially the Kempeitai (Japanese military police), were particularly cruel to the Chinese population. The most terrible event was the Sook Ching massacre. Chinese and Peranakan civilians were killed in revenge for their support of the war effort in China. The Japanese checked citizens (including children) to see if they were "anti-Japanese". If so, they were taken away in trucks to be executed. These mass killings claimed between 25,000 and 50,000 lives in Malaya and Singapore. The Japanese also killed many in the Indian community. They secretly killed about 150,000 Tamil Indians and tens of thousands of Malayalam from Malaya, Burma, and Singapore. The rest of the population suffered greatly during the three and a half years of Japanese occupation. Malays and Indians were forced to build the "Death Railway". Most of them died while building it.

Post-War Period (1945–1955)

After Japan surrendered to the Allies on 15 August 1945, Singapore faced a short period of violence and disorder. British troops, led by Lord Louis Mountbatten, returned to Singapore. They formally accepted the surrender of Japanese forces on 12 September 1945. A British Military Administration then governed the island until March 1946. Much of Singapore's infrastructure was destroyed during the war. This included electricity and water systems, telephone services, and port facilities. There was also a shortage of food, leading to poor nutrition and disease. High food prices, unemployment, and unhappy workers led to strikes in 1947. These caused huge disruptions in public transport and other services. By late 1947, the economy started to recover. This was helped by a growing demand for tin and rubber worldwide. But it took several more years for the economy to return to pre-war levels.

Britain's failure to defend Singapore made Singaporeans lose trust in their rulers. The years after the war saw people in Singapore become more politically aware. Feelings against colonial rule and for independence grew strong. This was shown by the slogan Merdeka, which means "independence" in Malay. The British were ready to slowly give Singapore and Malaya more self-governance. On 1 April 1946, the Straits Settlements was dissolved. Singapore became a separate Crown Colony with a civil government led by a Governor. In July 1947, new councils were set up. Elections for six members of the Legislative Council were planned for the next year.

First Legislative Council (1948–1951)

The first Singaporean elections, held in March 1948, were limited. Only six of the twenty-five seats on the Legislative Council were elected. Only British citizens could vote. Only 23,000 people, about 10% of those eligible, registered to vote. Other council members were chosen by the Governor or by business groups. Three of the elected seats were won by the new Singapore Progressive Party (SPP). This was a conservative party whose leaders were businessmen and professionals. They were not keen on pushing for immediate self-rule. The other three seats were won by independent candidates.

Three months after the elections, a communist uprising in Malaya, called the Malayan Emergency, began. The British took strong actions to control left-wing groups in both Singapore and Malaya. They introduced the controversial Internal Security Act. This law allowed people suspected of being "threats to security" to be held indefinitely without trial. Since left-wing groups were the strongest critics of the colonial system, progress towards self-government was delayed for several years.

Second Legislative Council (1951–1955)

A second Legislative Council election was held in 1951. The number of elected seats increased to nine. This election was again won mostly by the SPP, which took six seats. While this helped form a local government of Singapore, the colonial administration was still in charge. In 1953, with the communists in Malaya under control, a British Commission led by Sir George Rendel suggested a limited form of self-government for Singapore. A new Legislative Assembly would replace the Legislative Council. Twenty-five out of thirty-two seats would be chosen by popular election. A Chief Minister as head of government and a Council of Ministers (like a cabinet) would be chosen under a parliamentary system. The British would still control things like internal security and foreign affairs. They would also have the power to stop new laws.

The election for the Legislative Assembly on 2 April 1955 was a close contest. Several new political parties joined in. Unlike earlier elections, voters were automatically registered. This expanded the number of voters to about 300,000. The SPP lost badly, winning only four seats. The newly formed, left-leaning Labour Front won the most seats with ten. It formed a government with the UMNO-MCA Alliance, which won three seats. Another new party, the People's Action Party (PAP), won three seats.

The Fajar Trial (1953–1954)

The Fajar trial was the first sedition trial after the war in Malaysia and Singapore. Fajar was a publication of the University Socialist Club, mainly circulated on campus. In May 1954, members of the Fajar editorial board were arrested. They were accused of publishing a rebellious article called "Aggression in Asia." However, after three days of trial, the Fajar members were released. The famous English lawyer D.N. Pritt was the lead counsel, and Lee Kuan Yew, then a young lawyer, assisted him. The club's victory was an important moment in the journey towards decolonization in this part of the world.

Self-Government (1955–1963)

Partial Internal Self-Government (1955–1959)

David Marshall, leader of the Labour Front, became Singapore's first Chief Minister. He led a weak government. He received little help from both the colonial government and other local parties. Social unrest was growing. In May 1955, the Hock Lee bus riots broke out, killing four people. This greatly damaged Marshall's government. In 1956, the Chinese middle school riots happened among students. This increased tension between the local government and Chinese students and union members, who were thought to have communist sympathies.

In April 1956, Marshall led a group to London to ask for full self-rule in the Merdeka Talks. But the talks failed. The British did not want to give up control over Singapore's internal security. The British were worried about communist influence and labour strikes that were hurting Singapore's economy. They felt the local government was not good at handling earlier riots. Marshall resigned after the talks failed.

The new Chief Minister, Lim Yew Hock, cracked down on communist and leftist groups. He imprisoned many trade union leaders and some pro-communist members of the PAP using the Internal Security Act. The British government approved of Lim's strong actions against communist agitators. When new talks were held in March 1957, they agreed to grant complete internal self-government. The State of Singapore would be created, with its own citizenship. The Legislative Assembly would have fifty-one members, all chosen by popular election. The Prime Minister and cabinet would control all government matters except defense and foreign affairs. The governorship was replaced by a Yang di-Pertuan Negara or head of state. In August 1958, the State of Singapore Act was passed in the United Kingdom Parliament. This law set up the State of Singapore.

Full Internal Self-Government (1959–1963)

Elections for the new Legislative Assembly were held in May 1959. The People's Action Party (PAP) won by a huge margin, taking forty-three of the fifty-one seats. They achieved this by appealing to the Chinese-speaking majority, especially those in labour unions and student groups. Their leader, Lee Kuan Yew, a young lawyer educated in Cambridge, became Singapore's first Prime Minister.

At first, the PAP's victory worried foreign and local business leaders. This was because some party members were pro-communists. Many businesses quickly moved their headquarters from Singapore to Kuala Lumpur. Despite these concerns, the PAP government started a strong program to fix Singapore's economic and social problems. Economic development was managed by the new Minister of Finance, Goh Keng Swee. His plan was to encourage foreign and local investment. This included tax breaks and setting up a large industrial estate in Jurong. The education system was changed to train skilled workers. English was promoted over Chinese as the language of instruction. To stop labour unrest, existing labour unions were combined, sometimes by force, into one large group called the National Trades Union Congress (NTUC). The government closely watched this group. On the social side, a big and well-funded public housing program was launched to solve the long-standing housing problem. More than 25,000 tall, low-cost apartments were built in the first two years of the program.

Campaign for Merger

Even with their success in governing Singapore, PAP leaders like Lee and Goh believed Singapore's future was with Malaya. They felt that Singapore and Malaya had too strong historical and economic ties to remain separate. Also, Singapore lacked natural resources. Its entrepôt trade was declining, and its growing population needed jobs. They thought joining Malaya would help the economy by creating a common market. This would remove trade taxes and support new industries, solving unemployment.

Although the PAP leadership strongly pushed for a merger, the large pro-communist part of the PAP was against it. They feared losing influence because Malaya's ruling party, United Malays National Organisation, was strongly anti-communist. It would support the non-communist part of PAP against them. UMNO leaders were also unsure about the merger. They didn't trust the PAP government. They also worried that Singapore's large Chinese population would change the racial balance that their political power depended on. The issue became critical in 1961 when PAP minister Ong Eng Guan left the party. He then beat a PAP candidate in a special election. This threatened to bring down Lee's government.

Facing the possibility of a communist takeover, UMNO changed its mind about the merger. On 27 May, Malaya's Prime Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman, suggested forming a Federation of Malaysia. This would include the existing Federation of Malaya, Singapore, Brunei, and the British Borneo territories of North Borneo and Sarawak. UMNO leaders believed that the extra Malay population in Borneo would balance Singapore's Chinese population. The British government thought the merger would stop Singapore from becoming a communist haven. Lee called for a vote on the merger in September 1962. He started a strong campaign to support their merger proposal. The government likely had a big influence over the media.

The referendum did not have an option to object to the merger idea. This was because no one had raised that issue in the Legislative Assembly before. However, the method of merger had been debated by the PAP, Singapore People's Alliance, and the Barisan Sosialis, each with their own plans. The referendum was called to solve this issue.

The referendum had three choices. Option A was for Singapore to join Malaysia with full self-rule and certain conditions met. Option B was for full integration into Malaysia, like any other state, without such self-rule. Option C was to join Malaysia "on terms no less favourable than the Borneo territories." This noted why Malaysia wanted the Borneo territories to join. Option A received 70% of the votes. 26% of the ballots were left blank, as suggested by the Barisan Sosialis to protest Option A. The other two plans received less than two percent each.

On 9 July 1963, leaders from Singapore, Malaya, Sabah, and Sarawak signed the Malaysia Agreement. This agreement planned to create Malaysia on 31 August. However, on 31 August (the original Malaysia Day), Lee Kuan Yew stood at the Padang in Singapore and declared Singapore's independence by itself. On 31 August, Singapore declared its independence from the United Kingdom. Yusof bin Ishak became the head of state (Yang di-Pertuan Negara), and Lee Kuan Yew became prime minister. But Tunku Abdul Rahman postponed the full formation of Malaysia to 16 September 1963. This was to allow a United Nations mission to North Borneo and Sarawak to confirm they truly wanted to merge. Indonesia had objected to Malaysia's formation. On 16 September 1963, which was also Lee's fortieth birthday, he again stood at the Padang. This time, he announced Singapore as part of Malaysia. Lee promised loyalty to the Central Government, the Tunku, and his colleagues. He asked for "an honourable relationship between the states and the Central Government, a relationship between brothers, and not a relationship between masters and servants."

Singapore in Malaysia (1963–1965)

Merger Challenges

On 16 September 1963, Malaya, Singapore, North Borneo, and Sarawak merged to form Malaysia. The union was difficult from the start. During the 1963 Singapore state elections, a local branch of United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) took part. This was despite an earlier agreement with the PAP not to join state politics during Malaysia's early years. UMNO lost all its attempts, but relations between PAP and UMNO worsened. The PAP, in return, challenged UMNO candidates in the 1964 federal election as part of the Malaysian Solidarity Convention. They won one seat in the Malaysian Parliament.

Growing Tensions

Racial tensions grew. Ethnic Chinese and other non-Malay groups in Singapore disagreed with policies that favoured Malays. These included quotas for Malays and special privileges guaranteed under Article 153 of the Constitution of Malaysia. There were also other financial benefits given mostly to Malays. Lee Kuan Yew and other political leaders started to ask for fair and equal treatment for all races in Malaysia. Their rallying cry was "Malaysian Malaysia!".

Meanwhile, Malays in Singapore were increasingly angered by the federal government's claims that the PAP was treating Malays badly. The outside political situation was also tense. Indonesian President Sukarno declared a state of Konfrontasi (Confrontation) against Malaysia. He started military actions against the new nation. This included the bombing of MacDonald House in Singapore on 10 March 1965 by Indonesian commandos, which killed three people. Indonesia also tried to stir up trouble to provoke Malays against Chinese. The most well-known riots were the 1964 Race Riots. They first happened on Prophet Muhammad's birthday on 21 July. Twenty-three people were killed and hundreds injured. During the unrest, food prices soared when the transport system was disrupted, causing more hardship.

The state and federal governments also had economic disagreements. UMNO leaders feared that Singapore's economic power would eventually shift political power away from Kuala Lumpur. Despite an earlier agreement to create a common market, Singapore still faced restrictions when trading with the rest of Malaysia. In response, Singapore refused to give Sabah and Sarawak the full amount of loans they had agreed to for the economic development of the two eastern states. The Bank of China branch in Singapore was closed by the Central Government in Kuala Lumpur. It was suspected of funding communists. The situation became so bad that talks between UMNO and the PAP broke down. Abusive speeches and writings became common on both sides. UMNO extremists called for the arrest of Lee Kuan Yew.

Separation from Malaysia

Seeing no other way to avoid more violence, the Malaysian Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman decided to expel Singapore from the federation. Goh Keng Swee, who had become doubtful about the merger's economic benefits for Singapore, convinced Lee Kuan Yew that the separation had to happen. UMNO and PAP representatives worked out the terms of separation in extreme secrecy. This was to present the British government with a done deal.

On 9 August 1965, the Parliament of Malaysia voted 126–0 to approve a change to the constitution. This change expelled Singapore from the federation. A tearful Lee Kuan Yew announced in a televised press conference that Singapore had become a sovereign, independent nation. In a widely remembered quote, he said: "For me, it is a moment of anguish. All my life, my whole adult life, I have believed in merger and unity of the two territories." The new state became the Republic of Singapore. Yusof bin Ishak was appointed as its first President.

Republic of Singapore (1965–Present)

Building a Nation (1965–1979)

After suddenly gaining independence, Singapore faced an uncertain future. The Konfrontasi was still ongoing. The conservative UMNO group strongly opposed the separation. Singapore faced dangers of attack by the Indonesian military and being forced back into Malaysia on bad terms. Many international news outlets doubted Singapore's chances of survival. Besides the issue of being a sovereign nation, urgent problems included unemployment, housing, education, and a lack of natural resources and land. Unemployment was between 10% and 12%, threatening to cause civil unrest.

Singapore immediately sought international recognition for its independence. The new state joined the United Nations on 21 September 1965, becoming the 117th member. It joined the Commonwealth in October that year. Foreign minister Sinnathamby Rajaratnam led a new foreign service. This helped Singapore assert its independence and build diplomatic ties with other countries. On 22 December 1965, the Constitution Amendment Act was passed. Under this act, the Head of State became the President, and the State of Singapore became the Republic of Singapore. Singapore later helped found the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on 8 August 1967. It was admitted into the Non-Aligned Movement in 1970.

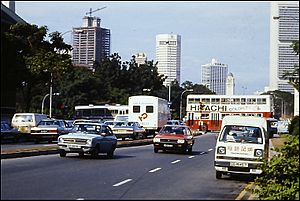

The Economic Development Board was set up in 1961. Its job was to create and carry out national economic plans. It focused on promoting Singapore's manufacturing sector. Industrial estates were built, especially in Jurong. Foreign investment was attracted to the country with tax incentives. This industrialization changed the manufacturing sector. It began producing higher-value goods and earning more money. The service industry also grew at this time. This was driven by demand for services from ships calling at the port and increasing business. This progress helped reduce the unemployment crisis. Singapore also attracted big oil companies like Shell and Esso. They set up oil refineries in Singapore. By the mid-1970s, Singapore became the third-largest oil-refining centre in the world. The government invested heavily in an education system. It adopted English as the teaching language and focused on practical training. This helped develop a skilled workforce suitable for industry.

The lack of good public housing, poor sanitation, and high unemployment led to social problems, from crime to health issues. Many squatter settlements caused safety hazards. The Bukit Ho Swee Fire in 1961 killed four people and left 16,000 homeless. The Housing Development Board (HDB), set up before independence, continued to be very successful. Huge building projects provided affordable public housing to move the squatters. Within ten years, most of the population lived in these apartments. The Central Provident Fund (CPF) Housing Scheme, started in 1968, allowed residents to use their required savings to buy HDB flats. This gradually increased home-ownership in Singapore.

British troops stayed in Singapore after its independence. But in 1968, London announced it would withdraw its forces by 1971. With secret help from military advisers from Israel, Singapore quickly built up the Singapore Armed Forces. This was done with a national service program started in 1967. Since independence, Singapore's defense spending has been about five percent of its GDP.

The 1980s and 1990s: Modernisation

Economic success continued through the 1980s. The unemployment rate dropped to 3%. Real GDP grew by about 8% each year until 1999. In the 1980s, Singapore started to move into higher-technology industries. This included the wafer fabrication sector. This was to compete with its neighbours, who now had cheaper labour. Singapore Changi Airport opened in 1981. Singapore Airlines grew into a major airline. The Port of Singapore became one of the world's busiest ports. The service and tourism industries also grew hugely during this time. Singapore became an important transport hub and a major tourist destination.

The Housing Development Board (HDB) continued to build public housing. New towns, like Ang Mo Kio, were designed and built. These new housing estates have larger, better apartments and more facilities. Today, 80–90% of the population lives in HDB apartments. In 1987, the first Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) line began operating. It connected most of these housing estates and the city centre.

The political situation in Singapore continues to be dominated by the People's Action Party. The PAP won all parliamentary seats in every election between 1966 and 1981. Some activists and opposition politicians call the PAP's rule authoritarian. They see the government's strict control of political and media activities as limiting political rights. The conviction of opposition politician Chee Soon Juan for illegal protests and lawsuits against J.B. Jeyaretnam have been cited as examples. The lack of separation of powers between the courts and the government led to more accusations of unfair justice.

The government of Singapore made several important changes. Non-Constituency Members of Parliament were introduced in 1984. This allowed up to three losing candidates from opposition parties to be appointed as MPs. Group Representation Constituencies (GRCs) were introduced in 1988. These created multi-seat election areas, meant to ensure minority representation in parliament. Nominated Members of Parliament were introduced in 1990. This allowed non-elected, non-partisan MPs. The Constitution was changed in 1991. It created an Elected President who has veto power over national reserves and public office appointments. Opposition parties have complained that the GRC system makes it hard for them to gain seats in parliamentary elections in Singapore. They also say the plurality voting system tends to exclude smaller parties.

In 1990, Lee Kuan Yew handed over leadership to Goh Chok Tong. He became Singapore's second prime minister. Goh showed a more open and consultative leadership style as the country continued to modernize. In 1997, Singapore felt the effects of the Asian financial crisis. Tough measures, like cuts in CPF contributions, were put in place.

Lee's programs in Singapore greatly influenced China's Communist leaders. Especially under Deng Xiaoping, they made a big effort to copy his policies of economic growth, entrepreneurship, and quiet suppression of disagreement. Over 22,000 Chinese officials were sent to Singapore to study its methods.

21st Century Singapore (2001–Present)

Singapore faced some of its biggest post-war challenges in the early 2000s. These included a plot to attack embassies in 2001, the SARS outbreak in 2003, the H1N1 pandemic in 2009, and the COVID-19 pandemic between January 2020 and April 2022.

More effort was put into promoting social integration and trust among different communities. There were also increasing reforms in the Education system. Primary education was made compulsory in 2003.

In 2004, then Deputy Prime Minister of Singapore Lee Hsien Loong, the eldest son of Lee Kuan Yew, took over from Goh Chok Tong. He became Singapore's third prime minister. He introduced several policy changes. These included reducing national service duration from two and a half years to two years. He also legalized casino gambling. Other efforts to raise the city's global profile included bringing back the Singapore Grand Prix in 2008. Singapore also hosted the 2010 Summer Youth Olympics.

The general election of 2006 was important because of the widespread use of the internet and blogging. People used them to cover and comment on the election, bypassing official media. The PAP stayed in power, winning 82 of the 84 parliamentary seats and 66% of the votes.

On 3 June 2009, Singapore celebrated 50 years of self-governance.

Singapore's efforts to become a more attractive tourist destination grew further in March 2010. Universal Studios Singapore opened at Resorts World Sentosa. In the same year, Marina Bay Sands Integrated Resorts also opened. Marina Bay Sands was called the world's most expensive standalone casino property at S$8 billion. On 31 December 2010, it was announced that Singapore's economy grew by 14.7% for the whole year. This was the best growth ever recorded for the country.

The general election of 2011 was another significant election. It was the first time a Group Representation Constituency (GRC) was lost by the ruling PAP to the opposition Workers' Party. The final results showed a 6.46% swing against the PAP from the 2006 elections, to 60.14%. This was its lowest since independence. Nevertheless, PAP won 81 out of 87 seats and kept its majority in parliament.

Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore's founding father and first Prime Minister, died on 23 March 2015. Singapore declared a period of national mourning from 23 to 29 March. Lee Kuan Yew was given a state funeral.

The year 2015 also saw Singapore celebrate its Golden Jubilee, 50 years of independence. An extra holiday, 7 August 2015, was declared to celebrate this milestone. Fun packs, usually given to people attending the National Day Parade, were given to every Singaporean and Permanent Resident household. To mark this important event, the 2015 National Day Parade was the first to be held at both the Padang and the Float at Marina Bay. NDP 2015 was the first National Day Parade without founding leader Lee Kuan Yew, who had never missed one since 1966.

The 2015 general elections were held on 11 September, shortly after the 2015 National Day Parade. This election was the first since Singapore's independence where all seats were contested. It was also the first election after the death of Lee Kuan Yew. The ruling PAP received its best results since 2001 with 69.86% of the popular vote. This was an increase of 9.72% from the previous election in 2011.

Following changes to the Constitution of Singapore, Singapore held its first reserved presidential elections in 2017. This election was the first to be set aside for a specific racial group under a special rule. The 2017 election was reserved for candidates from the minority Malay community. Then Speaker of Parliament Halimah Yacob won the elections without opposition and became the eighth President of Singapore on 14 September 2017. She was the first female President of Singapore.

In July 2020, the ruling party, The People’s Action Party (PAP), won 83 out of 93 seats and 61.2% of the popular vote in the general election. This meant PAP won its 13th election in a row since Singapore's independence. However, the result was a significant drop from the 2015 election.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Singapur para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Singapur para niños

- History of Southeast Asia

- History of East Asia

- List of years in Singapore

- List of prime ministers of Singapore

- Military history of Singapore

- Timeline of Singaporean history

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |