Arthur Percival facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Arthur Ernest Percival

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

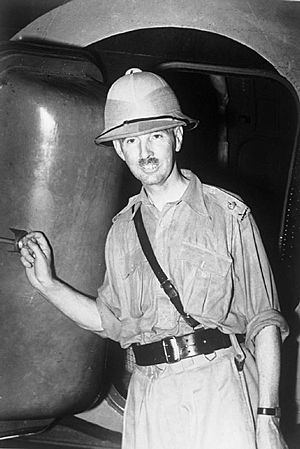

Percival, pictured here as GOC Malaya Command, December 1941

|

|||||||||||

| Born | 26 December 1887 Aspenden, Hertfordshire, England |

||||||||||

| Died | 31 January 1966 (aged 78) Westminster, London, England |

||||||||||

| Allegiance | United Kingdom | ||||||||||

| Service/ |

British Army | ||||||||||

| Years of service | 1914–1946 | ||||||||||

| Rank | Lieutenant-General | ||||||||||

| Service number | 8785 | ||||||||||

| Unit | Essex Regiment Cheshire Regiment |

||||||||||

| Commands held | Malaya Command (1941–1942) 44th (Home Counties) Infantry Division (1940–1941) 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division (1940) 2nd Battalion, Cheshire Regiment (1932–1934) 7th (Service) Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment (1918) |

||||||||||

| Battles/wars | First World War | ||||||||||

| Awards | Companion of the Order of the Bath Distinguished Service Order & Bar Officer of the Order of the British Empire Military Cross Mentioned in Despatches (3) Croix de guerre (France) |

||||||||||

| Spouse(s) |

Margaret Elizabeth MacGregor Greer

(m. 1927; died 1953) |

||||||||||

| Children |

|

||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 白思華 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 白思华 | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

Lieutenant-General Arthur Ernest Percival (born December 26, 1887 – died January 31, 1966) was an important officer in the British Army. He fought in the First World War and had a successful military career between the wars. However, he is best known for his defeat in the Second World War. During this time, he led British Empire forces in the Malayan Campaign and the Battle of Singapore.

Percival's surrender to the Imperial Japanese Army was the largest surrender in British military history. This event greatly damaged Britain's reputation as a powerful empire in East Asia. Some people, like Sir John Smyth, argued that the real problem was not Percival's leadership. Instead, they blamed the lack of money for Malaya's defenses and the fact that the army was not well-trained or equipped.

Contents

Early Life and Military Beginnings

Childhood and Education

Arthur Ernest Percival was born on December 26, 1887, in Aspenden, Hertfordshire, England. He was the second son of Alfred Reginald and Edith Percival. His father managed a large estate.

Percival first went to school in Bengeo. In 1901, he attended Rugby School, a famous boarding school. He studied Greek and Latin but was not a top student in these subjects. He was better at sports, playing cricket and tennis, and running cross country. He also became a colour sergeant in the school's military training group. Before the First World War began in 1914, he worked as a clerk in London.

Joining the First World War

Percival joined the army on the very first day of the war, at age 26. He started as a private and was quickly promoted to temporary second lieutenant after just five weeks. By November, he became a captain. In 1915, he went to France with the 7th Battalion of the Bedfordshire Regiment.

In October 1916, Percival became a regular captain with the Essex Regiment. He was later promoted to temporary major and then temporary lieutenant-colonel in 1917. During Germany's Spring Offensive, Percival led a counter-attack that saved a French artillery unit. For this, he received the Croix de Guerre from France. He finished the war as a respected soldier.

Between the World Wars

Service in Russia and Ireland

After the First World War, Percival volunteered to serve in Russia in 1919. He was part of the British Military Mission during the Russian Civil War. He helped capture 400 enemy soldiers in an attack, earning another award for his bravery.

In 1920, Percival went to Ireland to fight against the Irish Republican Army (IRA) during the Irish War of Independence. He was an intelligence officer for the Essex Regiment. He was known for being very active in gathering information and setting up bicycle-riding 'Mobile Columns'. Some people accused him of using harsh methods with prisoners.

He captured two important IRA members, Tom Hales and Patrick Harte. For this, he was given the Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) award. Both prisoners later said they were badly treated while captured. Tom Barry, another IRA leader, later called Percival "the most vicious anti-Irish of all serving British officers." Percival later gave talks about his experiences in Ireland. He emphasized how important surprise attacks, intelligence gathering, and teamwork were.

Becoming a Staff Officer

From 1923 to 1924, Percival attended the Staff College, Camberley. This is where officers learn about military planning and leadership. He impressed his teachers and was chosen for faster promotion. After this, he spent four years in West Africa as a staff officer with the Nigeria Regiment. He was promoted to lieutenant-colonel in 1929.

In 1930, Percival studied at the Royal Naval College, Greenwich. From 1931 to 1932, he was an instructor at the Staff College. His mentor, Sir John Dill, helped him advance in his career. Dill thought Percival was a very promising officer. Percival then commanded the 2nd Battalion, the Cheshire Regiment, from 1932 to 1936, starting in Malta. In 1935, he attended the Imperial Defence College in London.

In March 1936, Percival became a full colonel. Until 1938, he was the Chief of Staff in Malaya. During this time, he realized that Singapore was not as safe as people thought. He considered that the Japanese might attack Malaya from the north, through Thailand. He even wrote a report about this possible attack plan, which turned out to be similar to what the Japanese did in 1941. In March 1938, Percival returned to Britain and was promoted to brigadier.

Second World War

From 1939 to 1940, Percival was a Brigadier for the I Corps of the British Expeditionary Force. He was then promoted to acting Major-General. In February 1940, he briefly became the General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division. He became Assistant Chief of the Imperial General Staff in 1940. After the Dunkirk evacuation, he asked for a command where he could be more active. He was given command of the 44th (Home Counties) Infantry Division. For nine months, he organized the defense of 62 miles (100 km) of the English coast from a possible invasion.

Percival's Warning About Singapore

In 1936, Major-General William Dobbie, who was in charge of Malaya, wondered if more troops were needed to stop the Japanese from setting up bases to attack Singapore. Percival, his Chief Staff Officer, was asked to figure out how the Japanese would most likely attack.

By late 1937, Percival's analysis confirmed that northern Malaya could be the main battleground. He predicted that the Japanese would land on the east coast of Thailand and Malaya. Their goal would be to capture airfields and control the sky. This would prepare for more Japanese landings in Johore to cut off communications and build another main base in North Borneo. From there, they could launch a final attack on eastern Singapore, especially the Changi area.

Commander in Malaya

In April 1941, Percival was promoted to acting Lieutenant-General. He was then appointed General Officer Commanding (GOC) Malaya. This was a very big promotion for him. He traveled to Malaya by flying boat, a long journey that took two weeks.

Percival had mixed feelings about his new job. He knew that if war didn't happen, he might be in a quiet command for years. But if war did break out, he would be in a difficult situation with too few forces.

For many years, Britain's defense plan for Malaya relied on sending a naval fleet to the new Singapore Naval Base. The army's job was to defend Singapore and southern Johore. However, with the war in Europe and Japan's actions in French Indochina, a sea-based defense became harder. So, the plan changed to use the RAF to defend Malaya until more troops could arrive. This led to building airfields in northern Malaya and along its east coast. Army units were spread out to protect these airfields.

When Percival arrived, he started training his army, which was not very experienced. Many of his Indian troops were new recruits. He traveled around the peninsula, encouraging the building of defenses around Jitra. He also approved a training manual called Tactical Notes on Malaya for all units.

In July 1941, Japan occupied southern Indochina. Britain, the United States, and the Netherlands responded by stopping trade with Japan, freezing their money, and cutting off supplies of oil, tin, and rubber. These actions aimed to make Japan stop its war in China. Instead, Japan decided to take the resources of South-East Asia by force. British Commonwealth reinforcements continued to arrive in Malaya. On December 2, two large warships, HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse, arrived in Singapore.

Japanese Attack and British Surrender

On December 8, 1941, the Japanese 25th Army, led by Lieutenant-General Tomoyuki Yamashita, launched an attack on the Malay Peninsula. The first Japanese invasion force landed at Kota Bharu on Malaya's east coast. This was a distraction. The main landings happened the next day in Thailand, with troops quickly moving into northern Malaya.

The Japanese advanced very quickly. On January 27, 1942, Percival ordered a full retreat across the Johore Strait to the island of Singapore. He organized a defense along the island's 70-mile (110 km) coastline. But the Japanese did not wait. On February 8, Japanese troops landed on the northwest part of Singapore island. After a week of fighting, Percival held his final meeting on February 15. The Japanese had already taken about half of Singapore. Percival was told that ammunition and water would run out the next day, so he agreed to surrender. The Japanese were also low on artillery shells, but Percival did not know this.

The Japanese demanded that Percival himself walk under a white flag to the Old Ford Motor Factory to discuss the surrender. A Japanese officer noted that Percival looked "pale, thin and tired." After a short discussion, it was agreed that British Empire troops would stop fighting at 8:30 pm. This happened even though Prime Minister Winston Churchill had ordered them to resist for longer.

Many people believe that 138,708 Allied soldiers surrendered or were killed by fewer than 30,000 Japanese. However, the larger number includes troops captured or killed during the Battle of Malaya and base troops. Many of the other troops were tired and poorly equipped after retreating. The smaller Japanese number only counts the front-line troops who invaded Singapore. British Empire battle losses since December 8 were 7,500 killed and 11,000 wounded. Japanese losses were about 3,500 killed and 6,100 wounded.

Why Singapore Fell

Churchill called the fall of Singapore "the worst disaster and largest surrender in British history." However, the British defense was that other areas, like the Middle East and the Soviet Union, received more soldiers and supplies. The desired air force strength of 300 to 500 aircraft was never reached. Also, the Japanese invaded with over two hundred tanks, but the British Army in Malaya had no tanks at all. In his book, The War in Malaya, Percival said this was the main reason for the defeat. He stated that important war materials that could have saved Singapore were sent to Russia and the Middle East. However, he also admitted that Britain was in a "life and death struggle in the West" and that this decision was "inevitable and right."

Percival was described as "a slim, soft spoken man" in 1918. But by 1945, his reputation had changed. Even his supporters called him "something of a damp squib" (meaning not very exciting or effective). The fall of Singapore made Percival seem like an ineffective "staff wallah" (someone who only works in an office), lacking toughness and aggression. He was tall, thin, with a clipped mustache and two front teeth that stuck out. He was not very good in photos, making him an easy target for cartoonists. His quiet manner and slight lisp also made him seem less impressive.

Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham, the Commander-in-Chief of the British Far East Command, did not allow Percival to launch Operation Matador. This was a plan to invade Thailand before the Japanese landed there. Brooke-Popham did not want to risk starting the war. Brooke-Popham was criticized for not strongly asking for more air support needed to defend Malaya.

Some people suggested that the government in London was more to blame than the British commanders in the Far East. Despite many requests, the British government did not send the necessary reinforcements. They also denied Brooke-Popham – and therefore Percival – permission to enter neutral Thailand. This meant it was too late to set up defenses there.

Percival also had difficulties with his commanders, Sir Lewis "Piggy" Heath and Gordon Bennett. Heath had been senior to Percival before Percival became GOC Malaya.

Percival was ultimately responsible for his soldiers. He did replace other officers, like Major-General David Murray-Lyon, when he felt they were not performing well. Perhaps his biggest mistake was refusing to build strong defenses in Johore or on the north shore of Singapore. He told his Chief Engineer, Brigadier Ivan Simson, that "Defenses are bad for morale – for both troops and civilians."

Percival also insisted on defending the north-eastern shore of Singapore most heavily. This was against the advice of the Allied supreme commander, General Archibald Wavell. Percival might have been focused on defending the Singapore Naval Base. He also spread his forces thinly around the island and kept few units as a backup. When the Japanese attacked in the west, the Australian 22nd Brigade took the main hit. Percival refused to send them more help because he still believed the main attack would be in the north-east. The Japanese attackers were almost out of ammunition when Percival surrendered. Before surrendering, he consulted his own officers.

In his post-war report, Percival said that the water supply was about to run out. The Municipal Water Engineer estimated on February 14 that water would be gone within 24-48 hours. This was a direct reason for the surrender. According to historical records, the engineer asked for ten trucks and a hundred Royal Engineers to fix water leaks caused by Japanese bombing. He only received one truck and ten engineers, and it was too late.

Being a Prisoner of War

Percival was briefly held prisoner in Changi Prison in Singapore. He was seen sitting with his head in his hands, sharing a house with seven brigadiers and other officers. He didn't talk much about his feelings but spent hours walking around, thinking about the defeat. To help with discipline, he re-formed a Malaya Command among the prisoners. He also gave lectures on the Battle of France to keep his fellow prisoners busy.

In August 1942, Percival and other senior British captives were moved from Singapore. He was first imprisoned in Formosa and then sent to Manchuria. There, he was held with other important prisoners, including American General Jonathan Wainwright, in a prisoner-of-war camp near Hsian.

As the war ended, an OSS team rescued the prisoners from Hsian. Percival was then taken with Wainwright to stand behind General Douglas MacArthur. This was when MacArthur confirmed the terms of the Japanese surrender on the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945. Afterward, MacArthur gave Percival a pen he had used to sign the treaty.

Percival and Wainwright then went to the Philippines to see the surrender of the Japanese army there. By a twist of fate, this army was commanded by General Yamashita. Yamashita was surprised to see Percival at the ceremony. On this occasion, Percival refused to shake Yamashita's hand, because he was angry about how prisoners of war had been treated in Singapore. The flag carried by Percival's group on the way to Bukit Timah was also present. It was flown when the Japanese formally surrendered Singapore back to Lord Louis Mountbatten.

Later Life

Percival returned to the United Kingdom in September 1945. He wrote his report at the War Office, but the UK Government changed it, and it was only published in 1948. He retired from the army in 1946 with the honorary rank of lieutenant-general.

After retiring, he held positions related to Hertfordshire, where he lived. He was an Honorary Colonel for a military unit from 1949 to 1954. He also served as a Deputy Lieutenant of Hertfordshire in 1951. He continued his connection with the Cheshire Regiment, becoming its Colonel from 1950 to 1955. His son, Brigadier James Percival, later continued this family connection.

Percival was respected for his time as a Japanese prisoner of war. He served as the life president of the Far East Prisoners of War Association (FEPOW). He worked hard to get compensation for his fellow captives. Eventually, he helped secure £5 million from frozen Japanese assets for this cause. This money was given out by the FEPOW Welfare Trust, where Percival was Chairman. He also protested against the film The Bridge on the River Kwai when it came out in 1957. He managed to get a statement added to the film saying it was a work of fiction. He also worked as President of the Hertfordshire British Red Cross.

Percival died at age 78 on January 31, 1966, in London. He is buried in the churchyard at Widford in Hertfordshire.

Family Life

On July 27, 1927, Percival married Margaret Elizabeth "Betty" MacGregor Greer in London. She was the daughter of a Protestant linen merchant from County Tyrone in Northern Ireland. They had met during his time in Ireland. They had two children: a daughter, Dorinda Margery, who became Lady Dunleath, and a son, Alfred James MacGregor, who was born in Singapore and also served in the British Army.

See Also

In Spanish: Arthur Ernest Percival para niños

In Spanish: Arthur Ernest Percival para niños

- Operation Krohcol

- Sir Shenton Thomas

Images for kids

-

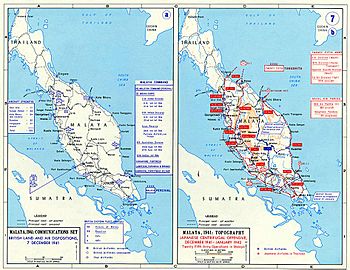

Map showing Malaya Command and the Japanese invasion of Malaya.

-

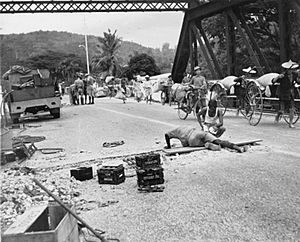

Lieutenant-General Percival, led by a Japanese officer, marches under a flag of truce to negotiate the surrender of Allied forces in Singapore, on February 15, 1942. It was the largest surrender of British-led forces in history.

-

Lieutenant-General Yamashita (seated, center) thumps the table to emphasize his demand for unconditional surrender. Lieutenant-General Percival sits between his officers, his hand to his mouth. (Photo from Imperial War Museum).

-

The signing of the Japanese surrender. MacArthur (sitting), with Generals Percival (background) and Wainwright (foreground) behind him.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |