History of Malaysia facts for kids

Malaysia is a country located on important sea routes, which has connected it to global trade and many different cultures for a very long time. The name "Malaysia" itself is quite new, created in the mid-1900s. However, modern Malaysia sees its history as stretching back thousands of years, including the ancient times of Malaya and Borneo.

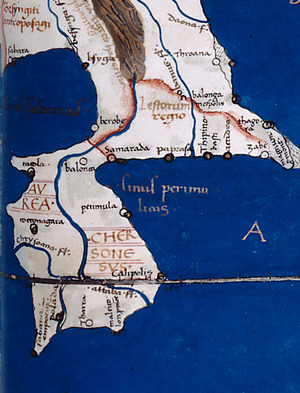

One of the first Western writings about this area is in Ptolemy's book Geographia from the 2nd century. It mentions a "Golden Chersonese", which is now believed to be the Malay Peninsula. In early times, Hinduism and Buddhism from India and China were very important. Their influence was strongest during the Srivijaya civilisation, based in Sumatra, from the 7th to the 13th centuries. This empire's power reached across Sumatra, West Java, East Borneo and the Malay Peninsula.

Even though Muslims traveled through the Malay Peninsula as early as the 10th century, Islam truly took hold in the 14th century. With Islam came the rise of several powerful kingdoms called sultanates. The most famous ones were the Sultanate of Malacca and the Sultanate of Brunei.

The Portuguese were the first European colonial power to arrive in Southeast Asia. They captured Malacca in 1511. This led to the creation of new sultanates like Johor and Perak. Later, the Dutch gained more control over the Malay sultanates from the 17th to 18th centuries, even capturing Malacca in 1641 with help from Johor. In the 19th century, the British set up bases in Jesselton, Kuching, Penang and Singapore. They eventually gained control over the area that is now Malaysia. Treaties like the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 and the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909 set the borders for British Malaya. During this time, many Chinese and Indian workers came to the Malay Peninsula and Borneo to work for the colonial economy.

The Japanese invasion during World War II ended British rule in Malaya. The occupation of Malaya, North Borneo and Sarawak from 1942 to 1945 sparked a strong feeling of nationalism among the people. After Japan was defeated by the Allies, the British set up the Malayan Union in 1946. But the Malays, led by the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), opposed it. So, the union was changed to the Federation of Malaya in 1948, becoming a protectorate until 1957. In the Peninsula, the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) started fighting the British. This led to a 12-year period of emergency rule from 1948 to 1960. Through military action and talks, Malaya gained independence on August 31, 1957. Tunku Abdul Rahman became the first Prime Minister.

On September 16, 1963, the Federation of Malaysia was formed. It brought together the Federation of Malaya, Singapore, Sarawak, and North Borneo (Sabah). However, in August 1965, Singapore left the federation and became a separate country. Malaysia also faced a conflict with Indonesia in the early 1960s. A racial riot in 1969 led to emergency rule and the creation of the National Operations Council (NOC). The NOC introduced the Rukun Negara in 1970, a national philosophy to promote unity. The New Economic Policy (NEP) was adopted in 1971 to reduce poverty and connect different races in the economy.

Under Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, Malaysia saw fast economic growth and city development starting in the 1980s. The economy changed from farming to manufacturing. Many huge projects were built, like the Petronas Towers, the North–South Expressway, and the new capital city of Putrajaya. The country faced the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s, but it recovered.

The Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition had ruled Malaysia since 1973. But in the 2018 general election, it was defeated by the Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition. In early 2020, Malaysia had a political crisis. This led to the PH government falling and a new coalition, Perikatan Nasional (PN), forming under Muhyiddin Yassin. During this time, the country faced many challenges, including the COVID-19 pandemic. In August 2021, Ismail Sabri became prime minister. The 2022 general election resulted in a hung parliament for the first time. Finally, Anwar Ibrahim became Malaysia's tenth prime minister on November 24, 2022, leading a grand coalition government.

Contents

Ancient History of Malaysia

The oldest signs of humans in Malaysia are stone hand axes found in Lenggong. These tools are about 1.83 million years old, making them some of the oldest evidence of human-like creatures in Southeast Asia.

The earliest proof of modern humans in Malaysia is a 40,000-year-old skull found in the Niah Caves in Sarawak. This skull, nicknamed "Deep Skull," was found in 1958. It belonged to a girl aged 16 or 17. Early people visited Niah Caves when Borneo was connected to mainland Southeast Asia. They survived by hunting, fishing, and gathering plants.

The oldest complete human skeleton found in Malaysia is the 11,000-year-old Perak Man, discovered in 1991. The native groups on the Malay Peninsula are the Negritos, the Senoi, and the Proto-Malays. The Negritos were likely the first inhabitants.

The Senoi group seems to be a mix of people. About half of their ancestors came from the Semang (an early Negrito group). The other half came from later migrations from Indochina about 4,000 years ago. These newcomers were farmers who brought their language and tools.

The Proto-Malays arrived in Malaysia by 1000 BC. They came from the Austronesian expansion. Around 300 BC, they were pushed inland by the Deutero-Malays. These people brought advanced farming techniques and metal tools. They are the direct ancestors of today's Malaysian Malays.

Early Kingdoms and Trade

In the first thousand years AD, Malay people became the main group on the peninsula. Early small states here were greatly influenced by Indian culture. This Indian influence began as early as the 3rd century BC.

Trade with India and China

Ancient Indian writings mention a "Suvarnadvipa" (Golden Peninsula), which some believe refers to the Malay Peninsula. The ancient text Vayu Purana also speaks of "Malayadvipa" with gold mines. The Greek geographer Ptolemy called the Malay Peninsula the Golden Chersonese.

Trade with China and India started in the 1st century BC. Chinese pottery pieces from the 1st century have been found in Borneo. In the early centuries, people in the Malay Peninsula adopted Indian religions like Hinduism and Buddhism. These religions greatly shaped their language and culture. The Sanskrit writing system was used from the 4th century.

Early Kingdoms (3rd–7th centuries)

Many Malay kingdoms existed in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, mostly on the eastern side of the Malay Peninsula. One of the earliest was Langkasuka in the north. It was connected to Funan in Cambodia. In the 5th century, the Kingdom of Pahang was mentioned in Chinese records. The Sejarah Melayu ("Malay Annals") says that the Khmer prince Raja Ganji Sarjuna founded the kingdom of Gangga Negara (modern-day Beruas, Perak) in the 8th century.

Gangga Negara

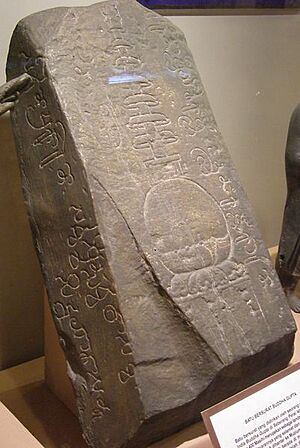

Gangga Negara is believed to be a lost Hindu kingdom mentioned in the Malay Annals. It covered parts of present-day Perak, Malaysia. Its name means "a city on the Ganges" in Sanskrit. Researchers think the kingdom was centered at Beruas. Artifacts like cannons, swords, coins, and pottery from the 5th and 6th centuries have been found there.

Old Kedah

Ptolemy's writings show that trade with India and China existed in Kedah from the 1st century AD. Coastal city-states in the region traded with China and India. They shared a common local culture. Rulers in the western part of the archipelago adopted Indian cultural and political ideas. This is seen in Indonesian art from the 5th century.

The Malay Peninsula was important for trade between China and South India. The Bujang Valley, located at the entrance of the Strait of Malacca, was often visited by Chinese and Indian traders. This is proven by the discovery of trade ceramics, sculptures, and temples from the 5th to 14th centuries. In Kedah, many Buddhist and Hindu remains have been found.

Srivijaya Empire (7th–13th century)

Between the 7th and 13th centuries, much of the Malay Peninsula was part of the Buddhist Srivijaya empire. Its center was near Palembang, Indonesia. For over six centuries, the rulers of Srivijaya controlled a large trading empire. Local kings pledged loyalty to the main ruler for mutual benefit. In 1025, the Chola dynasty from India attacked Palembang. By the end of the 12th century, Srivijaya's power had greatly reduced.

Relations with the Chola Empire

The relationship between Srivijaya and the Chola Empire of South India was friendly at first. But later, the Chola Empire invaded Srivijaya cities. In 1025 and 1026, the Chola king Rajendra Chola I attacked Gangga Negara and Kedah. A second invasion by Virarajendra Chola happened in the late 11th century. These invasions weakened Srivijaya's influence over Kedah and other northern Malay states. Even today, the Chola rule is remembered in Malaysia. Many Malaysian princes have names ending with Cholan or Chulan.

Decline of Srivijaya

The power of Srivijaya began to decline from the 12th century. Wars with Javanese and Indian states weakened it. The spread of Islam also reduced the power of the Buddhist rulers. Areas that converted to Islam early, like Aceh, broke away. By the late 13th century, the Siamese kings of Sukhothai controlled most of Malaya. In the 14th century, the Hindu Majapahit Empire took control of the peninsula.

In 1324, a Srivijaya prince, Sang Nila Utama, founded the Kingdom of Singapura (Temasek). He was later forced to leave Temasek by forces from Majapahit or Ayutthaya. He then went north and founded the Sultanate of Malacca in 1402. The Malacca Sultanate became the next major Malay power in the region.

Rise of Muslim States

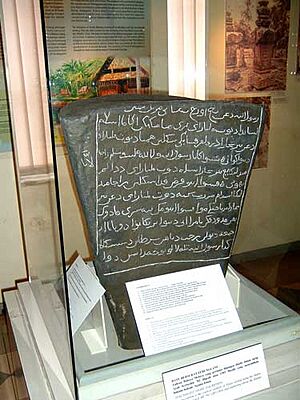

Islam came to the Malay Archipelago through Arab and Indian traders in the 13th century. It gradually became the religion of the rulers before spreading to common people.

Malacca Sultanate

Establishment

The port of Malacca was founded in 1400 by Parameswara. He was a Srivijayan prince fleeing Temasek (now Singapore). He settled at the mouth of the Bertam River and founded what became the Malacca Sultanate. He saw a mouse deer outsmarting a dog under a Malacca tree, which he took as a good sign. The Malacca Sultanate is often seen as the first independent state on the peninsula.

In 1404, the first official Chinese trade envoy arrived in Malacca. Later, Zheng He, a famous Chinese admiral, escorted Parameswara on his visits to China. Malacca's ties with Ming China protected it from attacks by Siam and Majapahit. This helped Malacca become a major trading hub between China, India, the Middle East, Africa, and Europe. The Chinese and Indians who settled here are the ancestors of today's Baba-Nyonya and Chitty communities.

Parameswara became a Muslim and took the title "Shah," calling himself Iskandar Shah. Chinese records say that in 1414, his son visited the Ming emperor and was recognized as the second ruler. Through Indian Muslims and Chinese Muslims, Islam became very common in the 15th century.

Rise of Malacca

After a period of paying tribute to the Ayutthaya, Malacca quickly became a powerful trading center. It controlled the important Straits of Malacca, which was vital for trade between China and India.

Malacca officially adopted Islam, and this helped Islam spread quickly throughout the archipelago. By the early 16th century, Islam was the main religion among Malays. Malacca's rule lasted over a century, but it became the center of Malay culture. Most future Malay states originated from this period. The Malay language also gained prestige and became the official language of many states. After Malacca fell, the Sultanate of Brunei became the main center of Islam.

16th–17th Century Politics

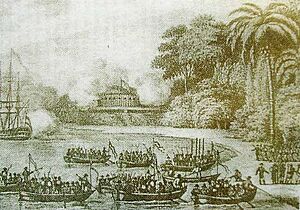

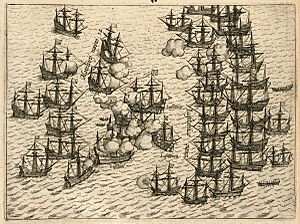

In 1511, Afonso de Albuquerque led a Portuguese expedition that captured Malacca. This was the first European colonial claim in what is now Malaysia. The son of the last Sultan of Malacca, Alauddin Riayat Shah II, fled south and founded the Sultanate of Johor in 1528. Another son founded the Perak Sultanate to the north. By the late 16th century, tin mines in northern Malaya made Perak wealthy.

After Malacca fell to Portugal, the Johor Sultanate and the Sultanate of Aceh in Sumatra competed for power. The Strait of Malacca became even more important for shipping. In 1607, the Sultanate of Aceh became the most powerful state. Under Sultan Iskandar Muda, Aceh controlled many Malay states, including Perak.

In the early 17th century, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) arrived. The Dutch were fighting Spain and allied with Johor. In 1641, the Dutch and Johor forces defeated the Portuguese in the Battle of Malacca. The Dutch took control of Malacca but did not interfere much in local matters.

Johor Sultanate

Johor was part of the Malacca Sultanate before the Portuguese captured Malacca in 1511. At its peak, Johor controlled modern-day Johor, Singapore, and parts of Sumatra. Johor and the Portuguese often fought in the 16th century. Aceh also launched raids against both Johor and the Portuguese.

In the early 17th century, the Dutch allied with Johor. In 1641, they defeated the Portuguese in Malacca. With the fall of Portuguese Malacca and the decline of Aceh, Johor began to regain its power. However, Johor later fought a war with Jambi (a Sumatran state) from 1666 to 1679. Johor won but was weakened. The Bugis people, who helped Johor, decided to stay and gained political influence.

In the 1690s, the Bugis had a major influence in Johor. After Sultan Mahmud II died in 1699, a power vacuum allowed the Bugis and Minangkabaus to gain more power. In 1718, Raja Kecil, a Minangkabau prince, captured Riau, the capital of Johor. But in 1722, Raja Kecil was overthrown with the help of the Bugis. Raja Sulaiman became the new Sultan but was largely controlled by the Bugis. In 1784, a major battle between the Bugis and the Dutch ended Bugis and Johor dominance.

Perak Sultanate

The Perak Sultanate was formed in the early 16th century by the eldest son of Mahmud Shah, the last Sultan of Malacca. He became Muzaffar Shah I, the first sultan of Perak. Perak became more organized after the Sultanate was established. In the 16th century, Perak became a source of tin ore.

Throughout the early 17th century, the Sultanate of Aceh often attacked the Malay Peninsula. Perak fell under Aceh's authority but remained independent from Siamese control. When the last Sultan of Perak died in 1635 without an heir, Aceh sent Raja Sulong to become the new Sultan.

Aceh's influence on Perak decreased when the Dutch East India Company (VOC) arrived in the mid-17th century. The Dutch wanted a monopoly on the tin trade. After some conflict, Perak signed a treaty with the Dutch in 1653, giving them exclusive rights to tin.

Pahang Sultanate

The Old Pahang Sultanate was established in the 15th century. It was an important power and controlled the entire Pahang basin. It started as a vassal to the Malacca Sultanate. Its first sultan was a Malaccan prince. Pahang later became independent and even rivaled Malacca. After Malacca fell in 1511, Pahang joined forces with Johor to try and expel the Portuguese.

Pahang had good relations with the Portuguese for a short time in the 17th century. However, in 1607, Pahang cooperated with the Dutch to try and remove the Portuguese. In 1615, the Acehnese invaded Pahang. This led to the union of the crowns of Pahang and Johor.

Selangor Sultanate

During the 17th century Johor-Jambi war, the Sultan of Johor hired Bugis mercenaries from Sulawesi. After Johor won, the Bugis stayed and gained power in the region. Many Bugis settled along the coast of Selangor. The Bugis, led by Raja Salehuddin, founded the Selangor Sultanate in 1766. Selangor is unique because it is the only state on the Malay Peninsula founded by the Bugis.

Brunei Sultanate

Before it became Muslim, Brunei was known as "Sribuza" in Arabic sources. It was a vassal state to Srivijaya. In the 14th century, Chinese records said that Boni (Brunei) invaded or controlled Sabah, parts of Sarawak, and other kingdoms in the Philippines.

By the 15th century, Brunei became a Muslim state. The king converted to Islam, and Muslim traders helped spread Islam. Under Sultan Bolkiah, the empire controlled coastal Borneo and reached parts of the Philippines.

16th–18th Century Brunei

In the 16th century, Brunei's influence extended to West Kalimantan. Other sultanates in the area were closely related to Brunei's royal family. The Brunei empire began to decline with the arrival of Western powers. Spain sent expeditions to invade Brunei's territories in the Philippines. Although the Spanish retreated, Brunei could not regain the lost territory.

19th Century Brunei

By the early 19th century, Sarawak was loosely controlled by the Brunei Sultanate. The interior of Sarawak suffered from tribal wars. In 1839, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin II asked his uncle to restore order. Around this time, James Brooke arrived. He helped suppress a revolt and, in return, received the title of Raja and the right to govern the Sarawak River District in 1841. This marked the beginning of the "White Rajahs" rule in Sarawak.

Struggles for Control

The weakness of the small Malay states led to the arrival of the Bugis people, who were escaping Dutch colonization. They settled on the peninsula and interfered with Dutch trade. They took control of Johor after the last Sultan of the old Malacca royal line was killed in 1699. The Bugis expanded their power in Johor, Kedah, Perak, and Selangor. The Minangkabau from Sumatra also migrated and established their own state in Negeri Sembilan. The fall of Johor created a power vacuum, partly filled by the Siamese kings of the Ayutthaya Kingdom. They made the five northern Malay states—Kedah, Kelantan, Patani, Perlis, and Terengganu—their vassals.

The economic importance of Malaya to Europe grew rapidly in the 18th century. The demand for Malayan tin and pepper increased. Gold mines were found in Kelantan and Pahang. This growth led to the first wave of foreign settlers, initially Arabs and Indians, then Chinese.

Siamese Expansion

Kedah

After the Fall of Ayutthaya in 1767, the Northern Malay Sultanates were temporarily free from Siamese rule. In 1786, British trader Francis Light leased Penang Island from Sultan Abdullah Mukarram Shah in exchange for military support against the Siamese. However, Siam regained control over the Northern Malay Sultanates. Francis Light failed to provide military help, and Kedah came under Siamese rule. In 1821, Siam invaded Kedah. The Burney Treaty of 1826 did not restore the exiled Kedah Sultan. He fought for his throne for twelve years. In 1842, Sultan Mukarram Shah accepted Siamese terms and was restored. The next year, Perlis was separated from Kedah and became a separate principality under Bangkok.

Kelantan and Terengganu

Around 1760, Long Yunus unified Kelantan. Later, Tengku Muhammad of Terengganu became its ruler. This led to a war against Terengganu by Long Yunus's son, Long Muhammad, who became Sultan Muhammad I. Terengganu prospered under Thai rule. The Burney Treaty of 1826 recognized Siamese claims over Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis, and Terengganu. These states were not represented in the treaty. In 1909, a new treaty transferred four of these states from Siamese to British control, except for Patani.

British Influence

English traders first visited the Malay Peninsula in the 16th century. Before the mid-19th century, British interests were mostly economic. The growing trade with China increased the East India Company's desire for bases. The first permanent British acquisition was Penang, leased in 1786. This was followed by Province Wellesley on the mainland. In 1795, the British occupied Dutch Melaka during the Napoleonic Wars.

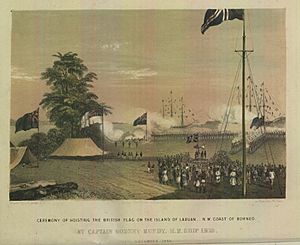

When Malacca was returned to the Dutch in 1818, Stamford Raffles acquired Singapore from the Sultan of Johor in 1819. The British then controlled Penang, Malacca, Singapore, and Labuan by 1846. These were set up as free ports to control trade through the Straits of Malacca. British influence grew as Malay rulers feared Siamese expansion and sought British protection.

In 1824, British control in Malaya was formalized by the Anglo-Dutch Treaty. It divided the Malay archipelago between Britain and the Netherlands. The British territories became the Straits Settlements, ruled by a governor.

Colonial Era

British in Malaya

Initially, the British did not interfere in the Malay states. But the importance of tin mining led to conflicts among the Malay aristocracy. This instability harmed trade, causing the British to intervene. Perak, with its rich tin mines, was the first Malay state to accept a British resident in 1874. The Pangkor Treaty of 1874 expanded British influence. British residents advised the Sultans and became the real rulers, except in matters of Malay religion and customs.

Johor was the only state to remain independent by modernizing and protecting British and Chinese investors. By the early 20th century, Pahang, Selangor, Perak, and Negeri Sembilan had British advisors. These were called the Federated Malay States. In 1909, Siam ceded Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis, and Terengganu to the British. These, along with Johor, were known as the Unfederated Malay States. The states under direct British control developed rapidly, becoming major suppliers of tin and rubber.

British in Borneo

In the late 19th century, the British also gained control of the north coast of Borneo. The eastern part (now Sabah) was under the Sultan of Sulu. The rest was Brunei's territory. In 1840, British adventurer James Brooke helped suppress a revolt in Sarawak. In return, he received the title of Raja and began ruling Sarawak as an independent state in 1841. The "White Rajahs" expanded Sarawak at Brunei's expense.

In 1881, the British North Borneo Company gained control of British North Borneo. It was ruled from London and became a British Protectorate. In 1888, what was left of Brunei became a British protectorate. In 1891, a treaty set the border between British and Dutch Borneo.

Race Relations During Colonial Era

Before colonial rule, "Malay" was not a fixed identity. The British introduced the idea of race to their colonial subjects. The British saw their empire as an economic venture. They were attracted to Malaya's tin and gold. Later, they grew plantation crops like rubber and palm oil. These industries needed many workers. The British brought in workers from India, mainly Tamil-speakers, to work on plantations. Chinese immigrants came to work in mines, mills, and docks. Soon, cities like Singapore, Penang, and Kuala Lumpur had Chinese majorities.

Workers were often treated badly. Many Chinese laborers fell into debt. Some Chinese workers were part of mutual aid societies. Chinese businesses, often with London firms, soon controlled the Malayan economy. Chinese bankers also lent money to Malay Sultans, giving them political influence. Many Chinese immigrants were men who planned to return home. But many stayed, married Malay women, or brought Chinese brides, forming permanent communities.

An Indian business class emerged in the early 20th century. However, most Indians remained poor, living in rural areas where rubber was grown. Traditional Malay society was harmed by the loss of political power to the British. The Sultans lost some prestige but were still respected by rural Malays. A small group of Malay nationalist thinkers emerged. Islam also saw a revival.

The British gave elite Malays positions in the police and administration. They aimed to control the education of young Malay elites. The Malay College was opened in 1905 for this purpose. This reflected the British policy that Malaya belonged to the Malays, and other races were temporary residents. This view led to resistance movements against British rule.

The Malay teachers' college fostered Malay nationalist feelings. In 1938, Ibrahim Yaacob formed the Kesatuan Melayu Muda (Young Malays Union or KMM). It was the first nationalist political group in British Malaya. It called for the unity of all Malays and a separate Malay identity.

World War II and the Emergency

When war broke out in the Pacific in December 1941, the British in Malaya were unprepared. The Japanese attacked from French Indo-China and quickly overran Malaya in two months. Singapore surrendered in February 1942. British North Borneo and Brunei were also occupied.

The Japanese government saw Malays as fellow Asians and encouraged a limited form of Malay nationalism. Most Sultans also worked with the Japanese. The KMM collaborated with the Japanese, hoping for a unified, independent "Melayu Raya." However, the Japanese treated the Chinese harshly. Up to 80,000 Chinese were killed in the sook ching. Chinese businesses were taken, and schools closed. The Chinese, led by the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), formed the Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA). With British help, the MPAJA became the most effective resistance force.

The Japanese also allowed Thailand to take back the four northern states that had been transferred to British Malaya in 1909. The loss of export markets caused widespread unemployment, making the Japanese unpopular.

After the war, ethnic tensions rose, and nationalism grew stronger. Malays were glad to see the British return in 1945. But people now wanted independence. Britain was financially weak and wanted to leave. The British planned a Malayan Union in 1944, combining the Malay states and Penang and Malacca into a single colony. But Malays strongly opposed this, especially the weakening of Malay rulers and granting citizenship to Chinese and other minorities.

In 1946, the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) was founded by Dato Onn bin Jaafar. UMNO wanted independence but only if Malays ran the new state. Faced with Malay opposition, the British dropped the equal citizenship plan. The Malayan Union was dissolved in 1948 and replaced by the Federation of Malaya, which restored the Malay rulers' power under British protection.

Meanwhile, the Communists began an open rebellion. The MCP, mostly Chinese, wanted immediate independence and equality for all races. In July 1948, after attacks on plantation managers, the government declared a State of emergency. The MCP was banned, and its members arrested. The Party retreated to the jungle and formed the Malayan Peoples' Liberation Army, mostly ethnic Chinese.

The Malayan Emergency lasted from 1948 to 1960. It involved a long fight by Commonwealth troops against the Communists. The British strategy was to separate the MCP from its supporters. They offered economic and political benefits to the Chinese and moved Chinese squatters into "New Villages." From 1949, the MCP's campaign weakened. The British High Commissioner, Sir Henry Gurney, was assassinated in 1951. But this terrorist tactic alienated many moderate Chinese. The arrival of Lt.-Gen Sir Gerald Templer in 1952 helped end the Emergency. Independence for the Federation was granted on August 31, 1957, with Tunku Abdul Rahman as the first prime minister.

Emergence of Malaysia

Struggle for Independent Malaysia

The Malayan Chinese Association (MCA) was formed in 1949. Its leader, Tan Cheng Lock, worked with UMNO to gain independence. They aimed for equal citizenship but with respect for Malay traditions. Tan formed a close partnership with Tunku Abdul Rahman, the leader of UMNO. The UMNO-MCA Alliance, later joined by the Malayan Indian Congress (MIC), won elections between 1952 and 1955.

The introduction of elected local government helped defeat the Communists. After Joseph Stalin's death in 1953, the MCP leadership split. Many militants gave up. By 1954, the Emergency was largely over.

In 1955 and 1956, UMNO, MCA, and the British worked on a constitution. It established equal citizenship for all races. In return, the MCA agreed that Malaya's head of state would be a Malay Sultan. Malay would be the official language, and Malay education and economic development would be supported. This meant Malays would largely run the country, but Chinese and Indians would have representation and economic protection. Independence came on August 31, 1957.

This left other British-ruled territories. Sarawak and North Borneo became British Crown Colonies after the Japanese surrender. Singapore gained autonomy in 1955, and Lee Kuan Yew became Prime Minister in 1959. The Sultan of Brunei remained a British client. From 1959 to 1962, the British government negotiated with these leaders and the Malayan government.

On May 27, 1961, Tunku Abdul Rahman proposed forming "Malaysia." It would include Brunei, Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak, and Singapore. This was to control communist activities, especially in Singapore. Including other British territories would balance the ethnic makeup, preventing a Chinese majority.

The Cobbold Commission studied the Borneo territories and approved a merger with North Borneo and Sarawak. North Borneo created a list of 20 points for its inclusion. Sarawak had an 18-point memorandum. Some points were included in the constitution. A referendum in Singapore showed 70% supported the merger. Brunei withdrew due to opposition and disagreements over oil money.

After negotiations, it was agreed that Malaysia would form on August 31, 1963. However, Indonesia and the Philippines strongly objected. Indonesia called it "neocolonialism," and the Philippines claimed North Borneo. Due to these objections, a UN team confirmed that North Borneo and Sarawak wanted to join. Malaysia officially formed on September 16, 1963, with Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak, and Singapore. In 1963, Malaysia's population was about 10 million.

Challenges of Independence

At independence, Malaya had economic advantages. It was a leading producer of rubber, tin, and palm oil. These exports gave the government money to invest in industry and infrastructure. The government wanted to reduce dependence on commodity exports and create new jobs.

Foreign Objection

Both Indonesia and the Philippines withdrew their ambassadors from Malaya on September 15, 1963. Indonesian President Sukarno saw Malaysia as a plot against his country. He supported a Communist rebellion in Sarawak. Indonesian forces entered Sarawak but were contained by Malaysian and Commonwealth troops. This period of Konfrontasi (confrontation) lasted until Sukarno's downfall in 1966. The Philippines claimed North Borneo, but President Ferdinand Marcos later dropped the claim in 1966.

Racial Issues

The inclusion of Singapore, with its large Chinese majority, upset many Malays. This increased the Chinese proportion in Malaysia to nearly 40%. Racial tensions grew, especially as Lee Kuan Yew's party threatened to run candidates in Malaya. Tunku Abdul Rahman asked Singapore to leave Malaysia. On August 9, 1965, the Malaysian Parliament voted to expel Singapore.

After Singapore left, the main issues in Malaysia were education and economic differences among ethnic groups. Malays were unhappy with the Chinese community's wealth. The MCA leaders struggled to defend Chinese interests while maintaining good relations with UMNO. The Education Act of 1961 made Malay and English the only teaching languages in secondary schools. Malay was the only language in state primary schools. Chinese and Indian primary schools could exist, but students had to learn Malay and follow a "Malayan curriculum." Malays also received preferential treatment in education and subsidies.

The government's economic policies aimed to shift economic power towards Malays. The First and Second Malayan Plans (1956–1960 and 1961–1965) invested heavily in rural Malay communities. Agencies like the Federal Land Development Authority (FELDA) helped Malays buy farms. The state also offered loans and favored Malay companies. This increased the Malay share of the economy.

Crisis of 1969 and Communist Insurgency

The policies weakened the MCA and MIC's support among Chinese and Indian voters. At the same time, many educated but underemployed Malays felt discontent. This led to the formation of new parties like the Malaysian People's Movement (Gerakan) in 1968. Other parties like the Islamic Party of Malaysia (PAS) and the Democratic Action Party (DAP) also gained support.

After the Malayan Emergency ended in 1960, the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), the armed wing of the Malayan Communist Party, regrouped at the Thai border. The insurgency officially restarted on June 17, 1968. The government responded with programs like the Security and Development Program (KESBAN) and Rukun Tetangga (Neighbourhood Watch).

In the May 1969 federal elections, the UMNO-MCA-MIC Alliance won only 48% of the vote. The MCA lost many seats. The opposition celebrated, leading to a Malay backlash. This quickly resulted in riots and inter-communal violence in Kuala Lumpur. The government declared a state of emergency. A National Operations Council, led by Deputy Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak, took power. Tunku Abdul Rahman was forced to retire in 1970.

The new government suspended Parliament and political parties. It imposed press censorship and restricted political activity. The Internal Security Act (ISA) allowed indefinite detention without trial. The Constitution was changed to make criticism of the monarchy, Malay special position, or Malay as the national language illegal.

In 1971, Parliament reconvened. A new government coalition, the Barisan Nasional, was formed in 1973. It included UMNO, MCA, MIC, Gerakan, and regional parties. Abdul Razak held office until 1976. He was succeeded by Hussein Onn, and then by Tun Mahathir Mohamad in 1981.

During these years, policies like the controversial New Economic Policy (NEP) transformed Malaysia's economy and society. The NEP aimed to increase the economic share of the bumiputras (Malays and indigenous people). Malaysia has since tried to balance economic development with policies that promote fair participation for all races.

Modern Malaysia

In 1970, most Malays living in poverty were rural workers. They were largely excluded from the modern economy. The government's response was the New Economic Policy (NEP) of 1971. Its goals were to end poverty and remove the link between race and wealth. This meant shifting economic power from the Chinese to the Malays.

To create jobs for Malay graduates, the government set up agencies like PERNAS, PETRONAS, and HICOM. These agencies hired many Malays and invested in growing industries. As a result, the Malay share of the economy increased significantly. While Chinese remained powerful economically, the distinction between Chinese and Malay businesses began to fade by 2000.

Mahathir Administration

Mahathir Mohamad became prime minister on July 16, 1981. He released political detainees and appointed Musa Hitam as his deputy. After the NEP ended in 1990, Mahathir announced Vision 2020. This plan aimed for Malaysia to become a fully developed country within 30 years. It also aimed to break down ethnic barriers. The National Development Policy (NDP) replaced the NEP, opening some programs to other ethnicities. Poverty was reduced, and income inequality narrowed.

Mahathir's government cut corporate taxes and eased financial rules to attract foreign investment. The economy grew rapidly until 1997. Many major infrastructure projects were started, including the Multimedia Super Corridor, Putrajaya, and the Bakun Dam.

In 1997, the Asian financial crisis hit Malaysia. The value of the ringgit dropped, and foreign investment left. Mahathir defied the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and his deputy, Anwar Ibrahim. He increased government spending and fixed the ringgit to the US dollar. Malaysia recovered faster than its neighbors. In 1998, Mahathir dismissed Anwar as finance minister and deputy prime minister. Anwar and his supporters started the Reformasi movement, protesting against the government.

Mahathir retired in October 2003 after 22 years in office. He was the world's longest-serving elected leader at that time.

Abdullah Administration

Abdullah Ahmad Badawi became the fifth Prime Minister. He promised to fight corruption, empowering anti-corruption agencies. He promoted Islam Hadhari, an interpretation of Islam that supports economic and technological development. His government also focused on reviving Malaysia's agriculture.

In the 2004 general election, Abdullah's Barisan Nasional won a huge victory. This was due to his popularity and Malaysia's strong economic recovery.

In November 2007, two anti-government rallies took place in Kuala Lumpur. The Bersih Rally called for electoral reform. The HINDRAF rally protested alleged discriminatory policies against ethnic Malays. The government tried to prevent these gatherings.

Abdullah Badawi was re-elected in the 2008 general election but with a reduced majority. His party lost its two-thirds majority and five states. He faced criticism for failing to combat corruption and for the election results. In October 2008, he announced his resignation. His deputy, Najib Razak, succeeded him in April 2009.

Najib Administration

1Malaysia campaign was introduced by Najib Razak in 2009. In 2011, Najib announced that the Internal Security Act 1960 would be replaced by two new laws. The ISA was replaced by the Security Offences (Special Measures) Act 2012 in 2012.

In February 2013, there was an incursion in Lahad Datu, Sabah. Militants from the Philippines arrived, claiming territory. Malaysian security forces repelled them. After this, the Eastern Sabah Security Command (ESSCOM) was established.

In March 2014, Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 vanished. Four months later, Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 was shot down over Ukraine.

On April 1, 2015, Najib introduced a 6 percent tax on goods and services. Later that year, his administration faced a scandal involving 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB). This state-owned investment fund was involved in a multibillion-dollar embezzlement and money-laundering scheme. This led to widespread calls for Najib's resignation. The Bersih movement held rallies from 2011 to 2016, demanding electoral reform and clean governance. Najib was also criticized for his wife's lavish lifestyle.

In response to corruption accusations, Najib tightened his power. He removed his deputy, suspended newspapers, and passed the National Security Council Bill. This bill gave the prime minister great powers. Living costs increased due to subsidy cuts and the 1MDB scandal. These issues contributed to Barisan Nasional losing the 2018 general elections.

Second Mahathir Administration

Mahathir Mohamad formed a new political party, the Malaysian United Indigenous Party (BERSATU). It teamed up with three other parties to form Pakatan Harapan. He was sworn in as the seventh Prime Minister of Malaysia on May 10, 2018, after winning the election. This was the first time since 1957 that the opposition coalition took control of the government.

Mahathir promised to "restore the rule of law" and investigate the 1MDB scandal. He barred Najib and his wife from leaving the country. Anwar Ibrahim was given a full royal pardon and released from prison. He was expected to succeed Mahathir.

The unpopular Goods and Services Tax was reduced to 0% on June 1, 2018, and later replaced with Sales Tax and Service Tax. Mahathir's administration reviewed all Belt and Road Initiative projects. He canceled some deals, saying Malaysia could not repay its obligations to China. Mahathir supported the 2018–19 Korean peace process and announced Malaysia would reopen its embassy in North Korea.

In October 2019, Mahathir announced the Shared Prosperity Vision 2030. This plan aimed to increase incomes for all ethnic groups and focus on technology. Malaysia's freedom of the press improved under his rule. Political infighting within Pakatan Harapan led to a political crisis in February 2020.

Muhyiddin Administration

On March 1, 2020, Muhyiddin Yassin was appointed as the eighth Prime Minister. He led the new Perikatan Nasional (PN) coalition government. During his time, the COVID-19 pandemic spread. Muhyiddin implemented the Malaysian movement control order (MCO) on March 18, 2020, to stop the disease from spreading.

On July 28, 2020, former Prime Minister Najib Razak was convicted of corruption. He became the first Prime Minister of Malaysia to be convicted. In January 2021, the Yang di-Pertuan Agong declared a national state of emergency due to the COVID-19 crisis and political infighting. Parliament and elections were suspended.

Muhyiddin started the country's vaccination program in February 2021. On March 19, 2021, North Korea cut diplomatic ties with Malaysia. Muhyiddin resigned as Prime Minister on August 16, 2021, after losing majority support.

Ismail Sabri Administration

Ismail Sabri Yaakob was sworn in as the ninth Prime Minister on August 21, 2021. He introduced the Keluarga Malaysia (Malaysian Family) idea. During his term, he lifted the Movement Control Order as the vaccination program expanded.

In August 2022, former Prime Minister Najib Razak was sent to prison. In late 2022, a constitutional amendment was passed to stop members of parliament from switching political parties. This led to an early general election in November 2022. The election resulted in a hung parliament, meaning no single coalition won a clear majority.

Anwar Administration

Anwar Ibrahim, the chairman of Pakatan Harapan (PH), was appointed as the 10th Prime Minister on November 24, 2022. He formed a grand coalition government with support from several parties. Anwar Ibrahim launched the Malaysia Madani concept in January 2023 as a new national policy.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Malasia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Malasia para niños

- The formation of Malaysia

- History of Singapore

- History of Brunei

- History of the Philippines

- History of Southeast Asia

- Japanese occupation of Malaya

- Japanese occupation of British Borneo

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |