Mahathir Mohamad facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Yang Amat Berbahagia Tun Dr.

Mahathir Mohamad

DK I (Johor) DK (Kedah) DK (Perlis) DKNS DK I (Brunei) DUK SMN SPMJ SPCM SSDK SSAP SSMT SPNS DUPN SPDK DUNM SBS SUMW DP PIS KmstkNO

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

محاضر محمد

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

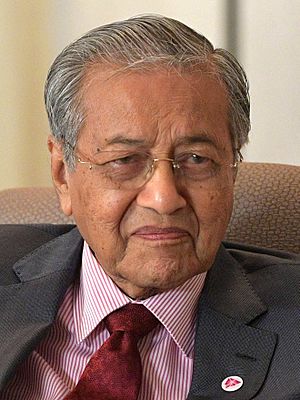

Mahathir in 2018

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4th & 7th Prime Minister of Malaysia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 May 2018 – 1 March 2020 Interim: 24 February – 1 March 2020 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Wan Azizah Wan Ismail | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Najib Razak | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Muhyiddin Yassin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 16 July 1981 – 31 October 2003 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Hussein Onn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Abdullah Ahmad Badawi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ministerial roles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1974–1978 | Minister of Education | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1976–1981 | Deputy Prime Minister | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1978–1981 | Minister of Trade and Industry | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1981–1986 | Minister of Defence | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1986–1999 | Minister of Home Affairs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1998–1999 | Minister of Finance | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2001–2003 | Minister of Finance | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2020 | Acting Minister of Education | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other roles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2003 | Secretary-General of the Non-Aligned Movement | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

Mahathir bin Mohamad

10 July 1925 Alor Setar, Kedah, Unfederated Malay States |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Citizenship | Malaysia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other political affiliations |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 7 (including Marina, Mokhzani and Mukhriz) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents | Mohamad Iskandar (father) Wan Tempawan Wan Hanapi (mother) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives | Mohamed Hashim Mohd Ali (brother-in-law) Ismail Mohamed Ali (brother-in-law) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | Kolej Sultan Abdul Hamid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | King Edward VII College of Medicine (MBBS) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Awards | Full list | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mahathir bin Mohamad (born 10 July 1925) is a Malaysian politician, writer, and doctor. He served as the Prime Minister of Malaysia two times. First, from 1981 to 2003, and then again from 2018 to 2020. He was the longest-serving prime minister in Malaysia's history, leading the country for a total of 24 years.

Mahathir's long political journey began in the 1940s. He helped transform Malaysia's economy and build new infrastructure. Because of his important role, he is known as the "Father of Modernisation" in Malaysia. As of July 2025, he is 100 years old and the oldest living former prime minister of Malaysia.

Contents

- Early Life and Education

- Medical Career

- Early Political Career

- Rising in Politics

- Mahathir's First Time as Prime Minister (1981–2003)

- After His First Term (2003–2015)

- Return to Politics (2015–2018)

- Second Time as Prime Minister (2018–2020)

- After His Second Term (2020–Present)

- Political Views and Ideas

- Personal Life

- Cultural Depictions

- Election Successes

- Awards and Recognitions

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life and Education

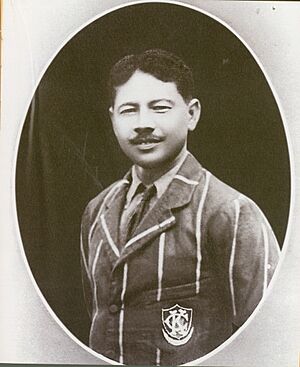

Mahathir was born in Alor Setar, Kedah, on 10 July 1925. His mother was Malay, and his father had Malay and Indian roots. His father was a school principal. Mahathir was the first Prime Minister of Malaysia not from a royal or very famous family.

He grew up with many siblings. His childhood home, which had no electricity, is now a tourist spot. As a child, Mahathir enjoyed games like snakes and ladders. He also showed creative talents in music, decorating, and carpentry. He once shared that he was bullied as a child. He sold balloons but was forced to buy food for a stronger peer.

Mahathir started school in 1930. He was a very hard-working student. His father's strictness encouraged him to study well. He became fluent in English and won language awards. In 1933, he joined a special English-medium secondary school. During World War II, schools closed. Mahathir then started a small business selling coffee and snacks. Even as Prime Minister, he often visited this market.

After the war, Mahathir finished secondary school with top grades. He went on to study medicine in Singapore. He enjoyed driving long distances during his college years. In 1947, he wrote an article about Malay women's freedom. He believed men should support women's independence.

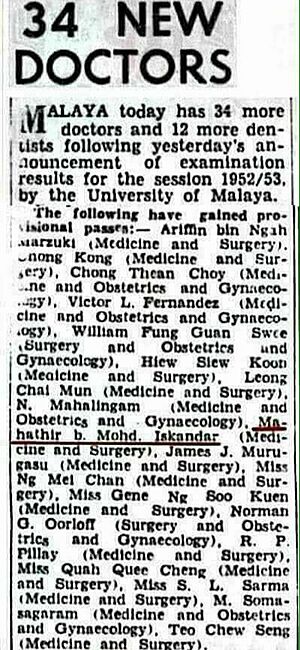

Medical Career

After finishing medical school in 1953, Mahathir worked as a doctor in different hospitals and clinics. He was the first doctor stationed in Langkawi in 1955. He saw how undeveloped the island was, which later inspired him to make it a big tourist spot.

Mahathir later opened his own private clinic, "Maha Klinik." It was the first private clinic owned by a Malay person in Malaysia. He was known as a caring doctor. He would visit patients' homes at any time, even walking across rice fields in the dark. If patients could not pay, he let them pay in small amounts or what they could afford.

Mahathir and his wife, Siti Hasmah, also helped with public health. He led the Kedah Tuberculosis Association. He visited rubber plantations to treat workers. Mahathir also invested in businesses like property and tin mining. He helped start the Malay Chamber of Commerce.

Early Political Career

After World War II, Mahathir became interested in politics. He joined protests against new rules that affected Malays. He also wrote articles promoting Malay rights. While working as a doctor, he became active in the UMNO party. By 1959, he was the party chairman in Kedah.

In 1964, Mahathir was elected to the Malaysian Parliament. He spoke strongly about Singapore's role in Malaysia. Singapore later left Malaysia in 1965. In 1969, Mahathir lost his parliamentary seat. After this, there were serious public disturbances. Mahathir openly criticized the government and was removed from his party, UMNO.

After leaving UMNO, Mahathir wrote a book called The Malay Dilemma. In this book, he shared his ideas for the Malay community. He believed there should be a balance between government support for Malays and healthy competition. His book was banned in Malaysia for some time. The ban was lifted when he became Prime Minister in 1981.

Rising in Politics

Mahathir rejoined UMNO in 1972. He quickly became an important figure. In 1973, he was appointed a Senator. He also became chairman of a food industry company. In 1974, he was elected to Parliament again. He then became the Minister for Education. During this time, he introduced a new school curriculum.

In 1976, Mahathir was chosen as the Deputy Prime Minister. This meant he was next in line to become Prime Minister. He also served as Minister of Trade and Industry. In this role, he pushed for "heavy industries." This included starting a national car industry. He traveled overseas to promote Malaysia.

In 1981, the Prime Minister, Hussein Onn, decided to step down. This opened the way for Mahathir to become the next leader.

Mahathir's First Time as Prime Minister (1981–2003)

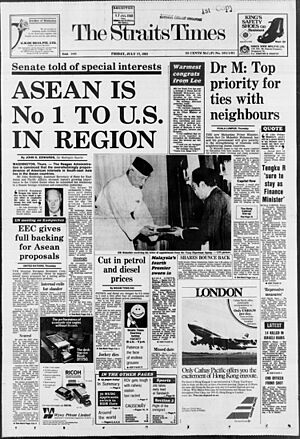

Mahathir became Malaysia's fourth Prime Minister on 16 July 1981. He quickly made changes. He freed some political prisoners and lifted the ban on his book. He also introduced a clock-in system for government workers. This helped improve punctuality and efficiency. He focused on strengthening ties with neighboring countries.

Key Changes and Economic Growth

Mahathir's time as Prime Minister saw Malaysia grow a lot. He wanted the government and private businesses to work together. This idea was called "Malaysia Incorporated." He also reduced the government's role in some areas. Many government services, like telecommunications and airlines, became private companies. This helped the economy grow.

Malaysia's economy changed from relying on raw materials to manufacturing and services. The number of companies grew a lot. By the end of his time, Malaysia was a leading emerging economy. It was one of the top trading nations in the world.

Handling Economic Challenges

During the 1997 Asian financial crisis, Malaysia faced big economic problems. Mahathir chose a different path than some other countries. He did not take a loan from the IMF. Instead, he put in place special rules to control money flow. These actions helped Malaysia recover quickly. Many experts later said his decisions were helpful.

Building Modern Malaysia

Mahathir started many big building projects. These projects helped modernize the country.

- National Car Project: In 1983, he launched Proton, Malaysia's first national car company. The Proton Saga became very popular. It even sold well in Europe.

- Langkawi's Development: He made Langkawi a duty-free zone. This helped it become a major tourist spot. He also improved its airport and hosted big events there.

- North–South Expressway: This long highway connects many parts of Peninsular Malaysia. It was completed in 1994.

- MEASAT Satellites: Malaysia launched its first communication satellites, MEASAT-1 and MEASAT-2. This improved broadcasting and telecommunications.

- Iconic Buildings: He supported building the Petronas Twin Towers and the Kuala Lumpur Tower. These became famous landmarks.

- Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA): A new, modern airport was built. It opened in 1998.

- Putrajaya: A new administrative city was built to ease congestion in Kuala Lumpur. Mahathir moved his office there in 1999. It is known as a "green city."

- Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC): This project aimed to make Malaysia a knowledge-based economy. It included developing Cyberjaya, known as Malaysia's "Silicon Valley".

"Look East" Policy

Mahathir introduced the "Look East Policy" in 1981. This policy encouraged Malaysians to learn from countries like Japan and South Korea. He wanted Malaysians to adopt their strong work ethic and development methods. Many Malaysian students and workers went to Japan for training. This policy helped strengthen ties and bring investments from East Asia.

He also started the "Buy British Last" policy for a short time. This was due to disagreements with the British government.

Health and Social Policies

Mahathir's government also focused on health. They encouraged private healthcare to grow. He received an award from the World Health Organization for his work in primary healthcare.

Changes to Royal Powers

Mahathir's government made changes to the Malaysian Constitution. These changes aimed to ensure that everyone, including the royal families, was subject to the law. This helped strengthen the rule of law in Malaysia.

Strengthening Defence

Malaysia also modernized its military under Mahathir. They bought new equipment and trained soldiers. Malaysia also sent peacekeepers to help in United Nations missions around the world.

Addressing Haze Pollution

During his time, haze from forest fires in Indonesia became a big problem. Mahathir's government worked to address this. They sent firefighters and launched cloud seeding operations. Malaysia also worked with Indonesia to find solutions. This led to a regional agreement to fight haze pollution.

Political Challenges

In 1987, Mahathir faced a challenge to his leadership within his party, UMNO. He managed to keep his position. Later, he formed a new version of the party called UMNO Baru.

Working with Other Countries

Mahathir focused on building strong relationships with many countries. He wanted Malaysia to trade with more nations, not just the usual ones. He encouraged Malaysian diplomats to focus on trade and investment.

He worked closely with Indonesia, especially on economic projects. He also strengthened ties with Japan and Russia. He met with leaders like Ronald Reagan and Vladimir Putin. Mahathir was a strong supporter of Bosnia and Herzegovina during its war. Malaysia sent aid and peacekeepers. A monument honoring Mahathir was even built in Sarajevo.

Elections and Retirement

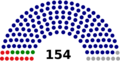

Mahathir led the Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition to many election victories. He won elections in 1982, 1986, 1990, 1995, and 1999. This showed strong public support for his leadership.

In 2002, Mahathir announced he would step down. He officially retired on 31 October 2003, after 22 years as Prime Minister. His deputy, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, took over. Mahathir was given the title "Father of Malaysia's Modernisation." His former home was turned into a national gallery.

After His First Term (2003–2015)

After retiring, Mahathir was given the highest honor in Malaysia, the title "Tun." He stayed very active, traveling and giving speeches. He believed in staying busy, saying, "Never retire. You have to work. When you work, it will keep you alive."

He served as an advisor for many important Malaysian companies. He was also the Chancellor of Universiti Teknologi Petronas. In 2006, he even co-founded a bakery called The Loaf.

Mahathir continued to share his opinions on national issues. He sometimes disagreed with the new Prime Minister, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi. He criticized some government decisions. He also started writing a blog to share his views.

In 2008, Mahathir left UMNO after the party lost many seats in the election. He rejoined in 2009 when Najib Razak became Prime Minister.

Return to Politics (2015–2018)

Even at 90 years old, Mahathir remained active in politics. He called for Prime Minister Najib Razak to resign due to a major financial scandal from the previous government. He also joined public protests.

In 2016, Mahathir left UMNO again. He then formed a new political party called BERSATU. By 2017, he joined the opposition group, Pakatan Harapan. He became their chairman and was chosen as their candidate for Prime Minister in the next election. His deputy candidate was Wan Azizah Wan Ismail, the wife of his former political rival, Anwar Ibrahim. Mahathir promised to seek a pardon for Anwar if they won.

Second Time as Prime Minister (2018–2020)

In the 2018 general election, Mahathir's Pakatan Harapan coalition won. This was a historic victory. Mahathir became Malaysia's seventh Prime Minister. He was the oldest serving state leader in the world at that time. His deputy, Wan Azizah Wan Ismail, became Malaysia's first female Deputy Prime Minister.

Key Actions and Policies

Mahathir promised to improve the rule of law. He reopened investigations into a major financial scandal from the previous government. He also stopped the former Prime Minister and his wife from leaving the country.

He formed a new cabinet. He removed an unpopular Goods and Services Tax. He also started a "no gifts policy" for government officials to prevent corruption. Mahathir aimed to reduce government spending. He canceled some expensive projects. Press freedom in Malaysia also improved during his term.

Foreign Relations

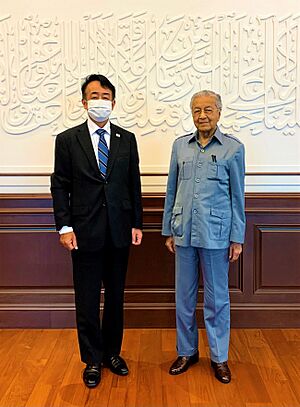

Mahathir worked to strengthen Malaysia's relationships with other countries. He visited Japan and Indonesia to ensure good ties. He also worked to improve economic and defense links with Russia. He met with leaders from the Philippines and China. He reviewed some large projects with China to make sure they were fair.

Mahathir spoke out against certain international events. He supported peace efforts in Korea. He also planned to reopen Malaysia's embassy in North Korea.

Political Changes and Resignation

Towards the end of 2019, disagreements grew within Mahathir's coalition. There were discussions about when he would hand over power to Anwar Ibrahim. In February 2020, Mahathir resigned as Prime Minister. The King then appointed him as an interim prime minister. Mahathir also left his party, BERSATU.

During his interim period, he introduced plans to help Malaysia's economy during the COVID-19 pandemic. On 29 February, the King appointed Muhyiddin Yassin as the new Prime Minister. Mahathir then left the office.

After His Second Term (2020–Present)

Even after stepping down again, Mahathir remained active. He formed a new political party called PEJUANG in 2020. He and other politicians protested against the government's handling of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2022, Mahathir decided to run in the general election again. However, he lost his parliamentary seat. This was his first election defeat in 53 years. After this, he said he would focus on writing about Malaysian history.

In 2023, Mahathir left PEJUANG and joined another party, Putra. He also started a campaign to unite Malays. He met with other political leaders to discuss important issues. In August 2024, Mahathir attended the Merdeka Day celebration. He was not officially invited but was welcomed by the public.

In early 2025, Mahathir's social media account was hacked. He also visited the site of a pipeline fire in April 2025. He attended the state funeral of former Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi. In May 2025, he shared his views on global politics.

Political Views and Ideas

Mahathir's political ideas changed over his long career. He supported "Asian values" and believed in strong economic growth. As a Muslim thinker, he held Islamic political views. He is respected in many developing and Muslim countries. This is partly because he helped Malaysia's economy grow.

He has been described as a supporter of Malay nationalism. In his book, The Malay Dilemma, he wrote about supporting the Malay community. However, he also believed in the idea of "Bangsa Malaysia," which means a united Malaysian nation. He worked to ensure that royal families were also subject to the law.

Mahathir often spoke critically about Western ideas and policies. He believed that developing countries should balance protecting the environment with using natural resources for growth. He argued that linking palm oil production to deforestation was unfair.

Personal Life

I don't smoke, I don't drink, and I don't overeat. I eat just enough to keep me going. Once people hit a certain age, there's a tendency to become overweight. Many develop a big stomach, and to feel satisfied, they eat and drink too much, which puts a strain on their heart. I've stayed around 62-64 kg for years, and I can still wear clothes I had made 30 years ago.

Mahathir lives a very disciplined life. He believes his good health comes from eating well and keeping his mind active by reading. He has kept the same weight for many years. His hobbies include sailing, horse riding, and carpentry. He even built a working steam train and a boat! He loves to read books by authors like Wilbur Smith.

Mahathir met his wife, Siti Hasmah, while they were studying medicine. They married in 1956. They have seven children, four biological and three adopted. In 2021, they celebrated their 65th wedding anniversary. His granddaughter says he is a family-oriented man who enjoys spending time with his grandchildren.

Even though he is a hard worker, Mahathir enjoys simple things. He likes cooking and driving his family to restaurants. He is a fan of the song "My Way." His childhood home in Alor Setar is now a public museum.

Mahathir has had some health issues over the years, but he has always recovered. On 10 July 2025, he celebrated his 100th birthday. He said it was a "normal day." Many people, including the current Prime Minister, sent him birthday wishes.

Cultural Depictions

Mahathir Mohamad's impact on Malaysia has been shown in various ways. A large mural of him was painted in Alor Setar in 2015. It features him with the Petronas Twin Towers and the Proton Saga car. These images represent his role as Malaysia's "Father of Modernisation."

Election Successes

Mahathir led the Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition to many election victories.

- In 1982, BN won a large majority of seats.

- In 1986, BN again secured a strong two-thirds majority.

- He won his third term in 1990 with another big victory.

- In 1995, BN won even more seats, showing strong support for Mahathir's plans.

- In 1999, BN won over two-thirds of the seats again.

These victories showed that Malaysians largely supported Mahathir's leadership and his vision for the country.

Awards and Recognitions

Mahathir has received many awards and honors from Malaysia and other countries. Some of these include:

- The highest federal award in Malaysia, the Seri Maharaja Mangku Negara, which gives him the title "Tun."

- The U Thant Peace Award from the United Nations in 1999.

- The Order of Friendship from Russia in 2003.

- The Order of the Paulownia Flowers from Japan in 2018.

- The Order of Pakistan in 2019.

- Many honorary doctorates from universities around the world.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Mahathir Mohamad para niños

In Spanish: Mahathir Mohamad para niños

- Mahathir, the Musical

- Mahathir Science Award

- List of oldest living state leaders