Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 facts for kids

The missing aircraft, 9M-MRO in December 2011

|

|

| Disappearance summary | |

|---|---|

| Date | 8 March 2014; 12 years ago |

| Summary | Inconclusive, some debris found |

| Place | Indian Ocean, probably Southern |

| Passengers | 227 |

| Crew | 12 |

| Fatalities | 239 (presumed) |

| Survivors | 0 (presumed) |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 777-200ER |

| Airline/user | Malaysia Airlines |

| Registration | 9M-MRO |

| Flew from | Kuala Lumpur International Airport |

| Flying to | Beijing Capital International Airport |

Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 (MH370/MAS370) was a passenger airplane that vanished on 8 March 2014. It was flying from Kuala Lumpur International Airport in Malaysia to Beijing Capital International Airport in China. The plane was a Boeing 777-200ER with the registration 9M-MRO.

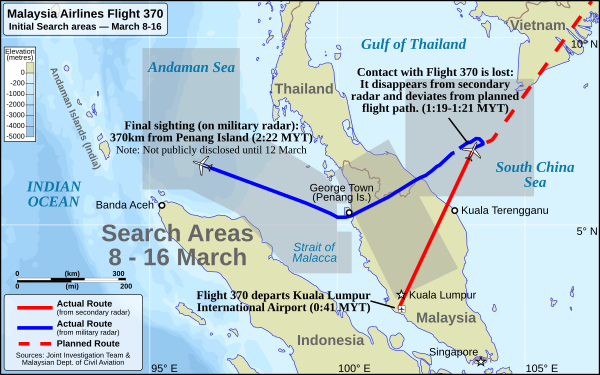

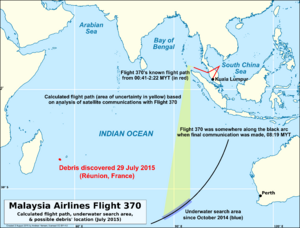

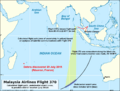

The crew last spoke to air traffic control (ATC) about 38 minutes after takeoff. This was when the flight was over the South China Sea. The plane disappeared from ATC radar screens a few minutes later. However, military radar tracked it for another hour. It flew west, away from its planned path, crossing the Malay Peninsula and Andaman Sea. It left radar range about 200 nautical miles (370 km) northwest of Penang Island.

All 227 passengers and 12 crew members are believed to have died. This made Flight 370 the deadliest event involving a Boeing 777 at the time. It was also the worst in Malaysia Airlines' history. Just four months later, Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 was shot down over eastern Ukraine. This incident was even deadlier. The loss of both flights caused big financial problems for Malaysia Airlines. The Malaysian government took over the airline in August 2014.

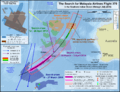

The search for Flight 370 became the most expensive aviation search ever. It first focused on the South China Sea and Andaman Sea. Later, experts analyzed the plane's automatic messages to an Inmarsat satellite. This showed a possible crash site in the southern Indian Ocean. Many people, especially families of the Chinese passengers, were upset about the lack of information early on. Most people on board Flight 370 were from China.

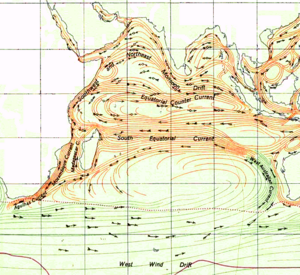

Several pieces of debris from the plane washed ashore in the western Indian Ocean in 2015 and 2016. Many of these were confirmed to be from Flight 370. After a three-year search covering 120,000 square kilometers (46,000 sq mi) of ocean, the plane was not found. The search was stopped in January 2017. A second search by a private company, Ocean Infinity, also ended without success in June 2018.

Investigators used data from the Inmarsat satellite. The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) first thought that a lack of oxygen (hypoxia) might have caused the event. However, investigators do not all agree on this. At different times, people thought the plane might have been hijacked. This included ideas about the crew or the plane's cargo. Many theories about the disappearance were reported. The Malaysian Ministry of Transport's final report in July 2018 did not find a clear cause. But it did point out that Malaysian ATC failed to try and contact the plane after it disappeared.

Because the cause is still unknown, new safety rules have been made. These rules aim to prevent similar events. They include longer battery life for underwater locator beacons. They also require longer recording times for flight data recorders and cockpit voice recorders. New rules also cover how planes report their position over the ocean.

Contents

Timeline of the Disappearance

Flight 370 was a Boeing 777-200ER. It last spoke to air traffic control at 1:19 AM on March 8, 2014. This was less than an hour after it took off. The plane was over the South China Sea. It disappeared from ATC radar screens at 1:22 AM.

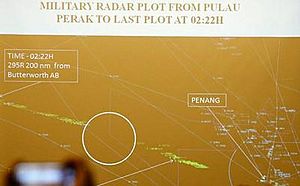

Military radar still tracked the plane. It turned sharply west from its original path. It flew across the Malay Peninsula. It kept going until it left military radar range at 2:22 AM. This was over the Andaman Sea, 200 nautical miles (370 km) northwest of Penang Island.

The search for the plane became the most expensive in aviation history. It started in the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea. This is where the plane's signal was last seen on radar. The search soon moved to the Strait of Malacca and Andaman Sea.

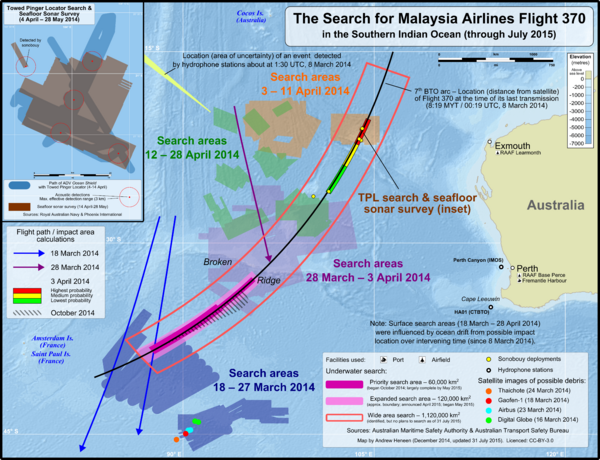

Experts analyzed satellite communications. They found that the flight continued until at least 8:19 AM. It flew south into the southern Indian Ocean. The exact location is still unknown. Australia took over the search on March 17. The focus then shifted to the southern Indian Ocean.

On March 24, the Malaysian government said the plane's last known location was far from any landing sites. They concluded that "Flight MH370 ended in the southern Indian Ocean." From October 2014 to January 2017, a large area of the seafloor was searched. This was about 1,800 km (1,100 mi) southwest of Perth, Australia. No sign of the plane was found.

Several pieces of plane debris were found on African coasts and Indian Ocean islands. The first piece was found on July 29, 2015, on Réunion. These pieces were confirmed to be from Flight 370. The main part of the plane has not been found. This has led to many theories about its disappearance.

On January 22, 2018, a private company called Ocean Infinity started a new search. They looked in a specific zone that was thought to be the most likely crash site. This search also ended without success after six months.

Neither the crew nor the plane's systems sent a distress signal. There were no signs of bad weather or technical problems before the plane vanished. Two passengers used stolen passports. They were investigated but were cleared of suspicion. Malaysian police looked into the captain as a possible suspect if human action caused the disappearance.

The plane's satellite data unit (SDU) lost power at some point. It reconnected to the satellite network at 2:25 AM. This was three minutes after the plane left radar range. Based on satellite data, the plane likely turned south after passing north of Sumatra. It then flew for six hours until it ran out of fuel.

Flight 370 is the second-deadliest event for a Boeing 777 and for Malaysia Airlines. Flight 17 was deadlier in both cases. Malaysia Airlines was already having money problems. These got worse after Flight 370 disappeared and Flight 17 was shot down. The airline was taken over by the government by the end of 2014.

The Malaysian government was criticized for not sharing information quickly. This was especially true in the first weeks of the search. Flight 370's disappearance showed the limits of plane tracking and flight recorders. For example, underwater locator beacons have limited battery life. New rules have been made since then. These include better plane position reporting over oceans. They also require longer recording times for cockpit voice recorders. New planes built after 2020 must have ways to recover flight recorders before they sink.

The Aircraft

Flight 370 was a Boeing 777-2H6ER. Its registration number was 9M-MRO. It was the 404th Boeing 777 ever made. It first flew on May 14, 2002. Malaysia Airlines received it on May 31, 2002.

The plane had two Rolls-Royce Trent 892 engines. It could carry 282 passengers. It had flown for 53,471.6 hours and completed 7,526 takeoffs and landings. The plane had not been in any major accidents before. However, it had a small incident in August 2012. Its wing tip was broken while taxiing at Shanghai Pudong International Airport.

Its last regular maintenance check was on February 23, 2014. The plane followed all safety rules for its body and engines. The crew oxygen system was refilled on March 7, 2014. This was a normal maintenance task, and nothing unusual was found.

The Boeing 777 first flew in 1994. It has a very good safety record. Since its first commercial flight in June 1995, only a few other Boeing 777s have been lost. These include British Airways Flight 38 in 2008 and Asiana Airlines Flight 214 in 2013. Also, Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 was shot down in July 2014.

People on Board

The plane had 12 Malaysian crew members and 227 passengers. The passengers were from 14 different countries. Malaysia Airlines released the names and nationalities of everyone on board. Later, it was found that two Iranian passengers were traveling with stolen passports.

The Crew

All 12 crew members were Malaysian citizens. There were two pilots and 10 cabin crew.

- The main pilot was 53-year-old Captain Zaharie Ahmad Shah. He joined Malaysia Airlines in 1981. He became a captain of the Boeing 777 in 1998. He had a lot of flying experience, with 18,365 hours.

- The co-pilot was 27-year-old First Officer Fariq Abdul Hamid. He joined Malaysia Airlines in 2007. Flight 370 was his last training flight before he was to be fully certified as a Boeing 777 first officer. He had 2,763 hours of flying experience.

The Passengers

Out of 227 passengers, 153 were Chinese citizens. This included a group of 19 artists returning from an art show. 38 passengers were Malaysian. The rest were from 12 other countries. Twenty passengers worked for a company called Freescale Semiconductor.

A Buddhist organization, Tzu Chi, sent teams to help the families of the passengers. Malaysia Airlines also sent its own helpers. They paid for family members to come to Kuala Lumpur and provided them with support.

Flight and Disappearance

Flight 370 was a regular flight on Saturday, March 8, 2014. It was supposed to fly from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, to Beijing, China. It was scheduled to leave at 12:35 AM local time and arrive at 6:30 AM. On board were two pilots, 10 cabin crew, 227 passengers, and 14,296 kg (31,517 lb) of cargo.

The flight was planned to last 5 hours and 34 minutes. It carried 49,100 kg (108,200 lb) of fuel, enough for 7 hours and 31 minutes. This extra fuel allowed for diversions to other airports if needed.

Departure

At 12:42 AM, Flight 370 took off from runway 32R. Air traffic control (ATC) told it to climb to a height of 18,000 feet. This was on a direct path to a navigation point called IGARI. The co-pilot spoke to ATC while the plane was on the ground. The captain spoke to ATC after takeoff.

Soon after takeoff, the flight was handed over to "Lumpur Radar" ATC. At 12:46 AM, Lumpur Radar cleared Flight 370 to climb to 35,000 feet. At 1:01 AM, the crew told Lumpur Radar they had reached 35,000 feet. They confirmed this again at 1:08 AM.

Communication Lost

The plane's last automatic position report was sent at 1:06 AM. This message showed the plane had 43,800 kg (96,600 lb) of fuel left. The last voice message to air traffic control was at 1:19:30 AM. Captain Zaharie confirmed the plane was moving from Lumpur Radar to Ho Chi Minh City ATC.

The crew was expected to contact ATC in Ho Chi Minh City as they entered Vietnamese airspace. This was just north of where contact was lost. Another pilot tried to call Flight 370 around 1:30 AM. He wanted to tell them to contact Vietnamese ATC. He said he heard "mumbling" and static. Calls to Flight 370's cockpit at 2:39 AM and 7:13 AM were not answered. But the plane's satellite system acknowledged them.

Radar Tracking

At 1:20:31 AM, Flight 370 was seen on radar at Kuala Lumpur ATC. It passed the navigation point IGARI in the Gulf of Thailand. Five seconds later, its symbol disappeared from radar screens. At 1:21:13 AM, Flight 370 disappeared from Kuala Lumpur ATC radar. It was also lost from Ho Chi Minh City ATC radar around the same time. Air traffic control uses secondary radar, which needs a signal from the plane's transponder. This means the transponder on Flight 370 stopped working after 1:21 AM.

Military radar showed Flight 370 turning right, then left, heading southwest. From 1:30:35 AM to 1:35 AM, military radar showed Flight 370 at 35,700 feet. It was flying at 496 knots (919 km/h). Flight 370 continued across the Malay Peninsula. Its altitude changed between 31,000 and 33,000 feet.

A civilian radar also detected an unknown plane between 1:30:37 AM and 1:52:35 AM. These tracks matched the military data. At 1:52 AM, Flight 370 was seen passing south of Penang island. From there, it flew across the Strait of Malacca. It passed near Pulau Perak at 2:03 AM. The last known radar detection was at 2:22 AM. This was 10 nautical miles (19 km) after passing a point called MEKAR. It was 247.3 nautical miles (458.0 km) northwest of Penang airport.

Countries were careful about sharing military radar information. This was because it could show their defense abilities. Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam all detected Flight 370 on radar before its transponder stopped working. But they did not provide much information about what happened afterward.

Satellite Communication Resumes

At 2:25 AM, the plane's satellite communication system sent a "log-on request" message. This was the first message since 1:07 AM. It was sent through a satellite operated by Inmarsat. After logging on, the plane's satellite system responded to hourly requests from Inmarsat. It also responded to two phone calls from the ground at 2:39 AM and 7:13 AM. No one in the cockpit answered these calls.

The last status request and plane confirmation happened at 8:10 AM. This was about 1 hour and 40 minutes after it was supposed to arrive in Beijing. The plane sent a final log-on request at 8:19:29 AM. After a response from the ground, it sent a "log-on acknowledgement" at 8:19:37 AM. This is the last piece of data from Flight 370. The plane did not respond to a request from Inmarsat at 9:15 AM.

Presumed Lost

Malaysia Airlines announced at 7:24 AM that contact with the flight was lost. They said the government had started search-and-rescue operations. The time of contact loss was later corrected to 1:21 AM. Neither the crew nor the plane's systems sent a distress signal. There were no signs of bad weather or technical problems before the plane vanished.

On March 24, Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak announced that Flight 370's last position was in the southern Indian Ocean. Since there were no places it could have landed, the plane must have crashed into the sea. Malaysia Airlines then announced that Flight 370 was presumed lost with no survivors. They told most families in person or by phone. Some received a text message saying the plane likely crashed with no survivors.

On January 29, 2015, Malaysia officially declared Flight 370 an "accident." All passengers and crew are presumed to have died. If this is confirmed, Flight 370 was the deadliest aviation event for Malaysia Airlines at the time. It was also the deadliest involving a Boeing 777. However, Flight 17 surpassed it 131 days later.

Reported Sightings

News reports mentioned several sightings of a plane that looked like the missing Boeing 777. For example, on March 19, 2014, CNN reported that fishermen and an oil rig worker saw the plane. A fisherman said he saw a very low-flying plane off the coast of Kota Bharu. An oil-rig worker claimed he saw a "burning object" in the sky. Indonesian fishermen reported seeing a plane crash near the Strait of Malacca.

The Search for MH370

A search-and-rescue effort began in Southeast Asia after Flight 370 disappeared. After analyzing satellite communications, the search moved to the southern Indian Ocean. Between March 18 and April 28, 2014, 19 ships and 345 military aircraft searched over 4.6 million square kilometers (1.8 million sq mi). The final part of the search involved mapping the seafloor. This was about 1,800 km (1,100 mi) southwest of Perth, Australia. The search was managed by the Joint Agency Coordination Centre (JACC). This Australian agency worked with Malaysia, China, and Australia.

On January 17, 2017, the official search for Flight 370 was stopped. It was the most expensive search in aviation history. No evidence of the plane was found, except for some debris on the coast of Africa. The final ATSB report in October 2017 said the underwater search cost US$155 million. Malaysia paid 58% of the cost, Australia 32%, and China 10%. The report also said the crash area was narrowed down to 25,000 square kilometers (9,700 sq mi). This was done using satellite images and debris drift analysis.

In January 2018, a private US company, Ocean Infinity, restarted the search. They used the ship Seabed Constructor. The search area was made much larger. By the end of May 2018, the ship had searched over 112,000 square kilometers (43,000 sq mi). This search also ended without success on June 9, 2018.

In March 2019, Malaysia said it would consider new "credible leads" for a search. Ocean Infinity said it was ready to search again if approved. They would only be paid if the wreckage was found. In March 2022, Ocean Infinity said it would try to resume the search in 2023 or 2024.

Search in Southeast Asia

The Kuala Lumpur Aeronautical Rescue Coordination Centre (ARCC) started coordinating search and rescue efforts at 5:30 AM. This was four hours after contact was lost. Searches began in the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea. On the second day, Malaysian officials said radar showed Flight 370 might have turned around. So, the search area grew to include part of the Strait of Malacca.

On March 12, the Royal Malaysian Air Force announced that an unknown plane, believed to be Flight 370, had flown across the Malay peninsula. It was last seen on military radar 370 km (200 nmi) northwest of Penang island. Search efforts then increased in the Andaman Sea and Bay of Bengal.

Signals between the plane and a satellite over the Indian Ocean showed the plane flew for almost six hours after its last radar sighting. Early analysis showed Flight 370 was along one of two arcs when its last signal was sent. On March 15, authorities stopped searching in the South China Sea, Gulf of Thailand, and Strait of Malacca. They focused on the two arcs. The northern arc (from northern Thailand to Kazakhstan) was soon ruled out. This was because the plane would have flown through heavily guarded airspace. Those countries said their military radar would have seen an unknown plane.

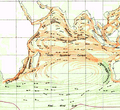

Search in the Southern Indian Ocean

The search then focused on the southern Indian Ocean, west of Australia. On March 17, Australia agreed to manage the search in this area.

First Search Efforts

From March 18 to March 27, 2014, the search focused on a 305,000 square kilometer (118,000 sq mi) area. This was about 2,600 km (1,600 mi) southwest of Perth. This area is known for strong winds, rough seas, and deep ocean floors. Satellite images showed several interesting objects. But none were found by planes or ships.

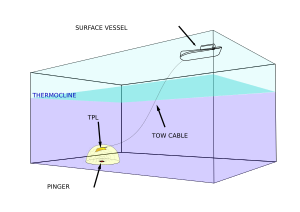

New estimates of the plane's path and fuel led to moving the search area. On March 28, it moved 1,100 km (680 mi) northeast. Another shift happened on April 4. From April 2 to 17, efforts were made to find the underwater locator beacons (ULBs). These "pingers" are attached to the plane's flight recorders. Their batteries were expected to run out around April 7.

Ships with special equipment tried to find the signals. Operators thought there was little chance of success because the search area was so huge. Between April 4 and 8, some sounds were detected. They were similar to the ULBs' signals. A sonar search of the seafloor near these sounds was done. But no sign of Flight 370 was found. A report in March 2015 said the ULB battery on Flight 370's flight data recorder might have expired in December 2012. This would make it less able to send signals.

Underwater Search

In June 2014, details of the next search phase were announced. This was called the "underwater search." More analysis of Flight 370's satellite communications helped find a "wide area search" along the "7th arc." This is where Flight 370 was when it last spoke to the satellite. The most important search area was in the southern part of this wide area.

Some equipment used for the underwater search works best when towed 650 feet (200 m) above the seafloor. Maps of the ocean floor in this region were not very clear. So, the seafloor had to be mapped before the underwater search began. This mapping started in May and covered about 208,000 square kilometers (80,000 sq mi). It stopped on December 17, 2014, to allow the ship to join the underwater search.

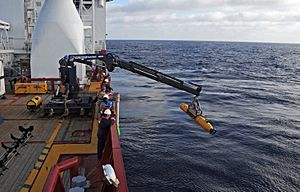

Malaysia, China, and Australia agreed to search 120,000 square kilometers (46,000 sq mi) of seafloor. This phase began on October 6, 2014. Three ships with special deep-water vehicles were used. These vehicles had sonar and video cameras to find plane debris. A fourth ship joined the search from January to May 2015. It used an AUV to search hard-to-reach areas.

After a piece of the plane (a flaperon) was found on Réunion, experts checked their calculations. They were still sure the search area was the most likely crash site. On January 17, 2017, the three countries announced they were stopping the search for Flight 370.

2018 Search

In October 2017, two companies offered to restart the search. In January 2018, Ocean Infinity announced it planned to search again. Malaysia approved this, but Ocean Infinity would only be paid if the wreckage was found. They used the Norwegian ship Seabed Constructor.

By late January, the ship reached the search zone. It moved to the area thought to be the most likely crash site. The planned search area was 33,012 square kilometers (12,746 sq mi). An extended area covered another 48,500 square kilometers (18,700 sq mi). By the end of May 2018, the ship had searched over 112,000 square kilometers (43,000 sq mi). It used eight AUVs.

Malaysia's new transport minister announced on May 23, 2018, that the search would end by the end of the month. Ocean Infinity confirmed its contract had ended on May 31. The search officially finished on June 9, 2018. The ocean floor mapping data collected during the search was given to a project to map the global ocean floor.

In March 2019, on the fifth anniversary, Malaysia said it would look at any "credible leads" for a new search. Ocean Infinity said it was ready to search again on the same "no-find, no-fee" basis. They believed the most likely location was still along the 7th arc. In March 2022, Ocean Infinity said it would try to resume its search in 2023 or 2024, if Malaysia approved.

Plane Parts Found

By October 2017, 20 pieces of debris believed to be from Flight 370 were found. They were recovered from beaches in the western Indian Ocean. 18 items were "very likely or almost certain" to be from MH370. The other two were "probably from the accident aircraft."

Flaperon

The first piece of debris confirmed to be from Flight 370 was a right flaperon (a part of the wing). It was found in July 2015 on a beach in Saint-André, Réunion. This island is in the western Indian Ocean, about 4,000 km (2,500 mi) west of the underwater search area.

The flaperon was sent to France for examination. On September 3, 2015, French officials announced that serial numbers on the flaperon's inside parts linked it "with certainty" to Flight 370. These numbers were found using a special camera.

After this discovery, French police searched the waters around Réunion for more debris. They found a damaged suitcase that might be linked to Flight 370. The location where the flaperon was found matched models of how debris would drift after 16 months. A Chinese water bottle and an Indonesian cleaning product were also found in the same area.

France searched the air around Réunion for more debris. They covered an area of 120 by 40 km (75 by 25 mi) along the east coast. Foot patrols also searched the beaches. Malaysia asked nearby countries to look for plane debris. By August 14, no debris from Flight 370 was found at sea off Réunion. But some items were found on land. Air and sea searches for debris ended on August 17.

Parts from the Right Stabilizer and Wing

In February 2016, an object with "NO STEP" written on it was found off Mozambique. Photos suggested it could be from the plane's horizontal stabilizer or wing edges. It was found by Blaine Gibson on a sandbank in the Bazaruto Archipelago. This was about 2,000 km (1,200 mi) southwest of where the flaperon was found. The part was sent to Australia. Experts said it was almost certainly a horizontal stabilizer panel from MH370.

In December 2015, Liam Lotter found a grey piece of debris on a beach in southern Mozambique. He only told authorities after reading about Gibson's find in March 2016. This piece was about 300 km (190 mi) from his own find. It was flown to Australia for analysis. It had a code, 676EB, which showed it was part of a Boeing 777 flap track fairing. The lettering matched Malaysia Airlines' stencils. This made it almost certain the part was from Flight 370.

The locations where these objects were found matched the drift model. This further supported that the parts could be from Flight 370.

Other Debris

On March 7, 2016, more debris, possibly from the plane, was found on Réunion. Malaysia's deputy transport minister said an "unidentified grey item with a blue border" might be linked to Flight 370. Malaysian and Australian authorities sent teams to check if it was from the missing plane.

On March 21, 2016, an archaeologist found a grey piece of debris near Mossel Bay, South Africa. It had a partial Rolls-Royce logo. Rolls-Royce made the plane's engines. Malaysia's transport ministry said it could be an engine cowling. Another possible piece of debris, thought to be from the plane's inside, was found on Rodrigues, Mauritius, in late March. On May 11, 2016, Australian authorities said these two pieces were "almost certainly" from Flight 370.

Flap and Further Search

On June 24, 2016, Australia's transport minister said a piece of plane debris was found on Pemba Island, off Tanzania. It was given to authorities for Malaysian experts to check. On July 20, the Australian government released photos of the piece. It was believed to be an outboard flap from one of the plane's wings. Malaysia's transport ministry confirmed on September 15 that the debris was from the missing plane.

On November 21, 2016, families of the victims said they would search for debris in December on Madagascar. On November 30, 2018, five pieces of debris were found between December 2016 and August 2018 on the Malagasy coast. Victims' relatives believed they were from MH370. They were given to Malaysia's transport minister.

A math professor, Goong Chen, suggested the plane might have entered the sea vertically. He argued that any other angle would have broken the plane into many pieces, which would have been found by now.

Investigation

International Help

Malaysia quickly formed a Joint Investigation Team (JIT). It included experts from Malaysia, China, the UK, the US, and France. The team followed international aviation rules. It had groups for airworthiness, operations, and human factors. The airworthiness group looked at maintenance and systems. The operations group reviewed flight recorders and weather. The human factors group investigated psychological and survival factors. Malaysia also set up three government committees. The criminal investigation was led by the Royal Malaysia Police. They were helped by Interpol and other law enforcement.

On March 17, Australia took charge of coordinating the search and recovery. For six weeks, Australian agencies worked to find the search area. They used information from the JIT and other sources. The Joint Agency Coordination Centre (JACC) managed the search. Later, the ATSB became responsible for defining the search area. A working group was created to find the plane's most likely position at the time of its last satellite message. This group included experts from many countries and companies.

As of October 2018, France was the only country still investigating. They wanted to check all technical data, especially from Inmarsat.

Reports on the Investigation

On March 8, 2015, one year after the disappearance, Malaysia's Ministry of Transport released an interim report. It focused on facts about the plane, not on possible causes. A short update was given in March 2016.

The final ATSB report was published on October 3, 2017. The final report from Malaysia's Ministry of Transport was released on July 30, 2018. This report did not give new information about what happened to MH370. But it did point out mistakes made by Malaysian air traffic controllers. They had limited efforts to contact the plane. After these findings, the Chairman of the Civil Aviation Authority of Malaysia, Azharuddin Abdul Rahman, resigned.

Possible Events During Flight

Power Interruption

The satellite communication link worked normally from before takeoff until 1:07 AM. At that time, it responded to a message. Messages continued to be sent to Flight 370 until 2:03 AM. But the plane did not respond. At some point between 1:07 AM and 2:03 AM, the satellite data unit (SDU) lost power. At 2:25 AM, the plane's SDU sent a "log-on request." It is unusual for this to happen during a flight. But it can happen for many reasons. Analysis suggests a power interruption during the flight is the most likely reason.

Unresponsive Crew or Hypoxia

The ATSB compared evidence from Flight 370 to other accidents. They looked at in-flight problems, gliding events, and unresponsive crew or hypoxia (lack of oxygen). They concluded that an unresponsive crew or hypoxia "best fit the available evidence." This was for the five hours the plane flew south over the Indian Ocean without communication. It likely flew on autopilot. Not all investigators agree on this theory. If no controls were used after the engines stopped and autopilot turned off, the plane would likely have crashed into the ocean.

Analysis of the flaperon showed the landing flaps were not extended. This supports the idea of a high-speed spiral dive. In May 2018, the ATSB again said the flight was not under control when it crashed.

Theories About Disappearance

Passenger Involvement

Two men boarded Flight 370 with stolen passports. This caused suspicion right after the disappearance. The passports, one Austrian and one Italian, had been reported stolen in Thailand. Interpol said both passports were in its database of stolen documents. No check was made against this database before the flight. Malaysia's Home Minister criticized immigration officials for not stopping these passengers. The two one-way tickets were bought through China Southern Airlines. It was reported that an Iranian ordered the cheapest tickets to Europe by phone in Bangkok and paid cash.

The two passengers were later identified as Iranian men, 19 and 29 years old. They had entered Malaysia with valid Iranian passports. They were believed to be asylum seekers. Interpol said it was "inclined to conclude that it was not a terrorist incident."

US and Malaysian officials checked the backgrounds of all passengers. On March 18, China said it had checked all its citizens on the plane. They ruled out any involvement in "destruction or terror attacks." One passenger, a flight engineer, was briefly suspected. This was because he had "aviation skills."

Crew Involvement

US officials believe someone in the cockpit reprogrammed the plane's autopilot to fly south over the Indian Ocean. Police searched the pilots' homes. They also looked at financial records for all 12 crew members. On April 2, 2014, Malaysia's Police Inspector-General said over 170 interviews were done. This included interviews with family members of the pilots and crew.

Media reports claimed Malaysian police saw Captain Zaharie as the main suspect. This was if human action caused the disappearance. The US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) rebuilt deleted data from Captain Zaharie's home flight simulator. But a Malaysian government spokesman said "nothing sinister" was found. The preliminary report in March 2015 said there was "no evidence of recent or imminent significant financial transactions" by any crew. It also said CCTV showed "no significant behavioral changes" in the pilots.

In 2016, a leaked US document said a route on the pilot's flight simulator matched the projected flight over the Indian Ocean. The ATSB confirmed this. But they stressed it did not prove the pilot's involvement. The Malaysian government also confirmed the finding.

In 2018, the pilot's sister said the safety report showed "nothing negative" about him. The report said there were seven "manually programmed" waypoints. These would create a path from Kuala Lumpur to the southern Indian Ocean. But the report found no unusual activities other than game-related flight simulations.

Cargo

Flight 370 carried 10,806 kg (23,823 lb) of cargo. Of this, 4,566 kg (10,066 lb) of mangosteen fruit and 221 kg (487 lb) of lithium-ion batteries were of interest. The mangosteens were loaded at Kuala Lumpur International Airport. They were inspected by agriculture officials. The batteries were part of a 2,453 kg (5,408 lb) shipment from Motorola Solutions. The rest was walkie-talkie chargers.

The batteries were packed according to safety rules. So, they were not considered dangerous goods. Lithium-ion batteries can cause intense fires if they overheat. This has led to strict rules for their transport on planes. Some airlines have stopped carrying large shipments of these batteries on passenger planes.

Aftermath

Criticism of Malaysian Officials

Public communication from Malaysian officials was confusing at first. The government and airline gave unclear, incomplete, and sometimes wrong information. Civilian officials sometimes disagreed with military leaders. They were criticized for giving out conflicting information, especially about the plane's last known location and time of contact.

Malaysia's acting Transport Minister denied problems between countries. But experts said regional conflicts caused trust issues. This made it hard to share information. One Chinese expert said countries were searching separately, not together. Vietnam temporarily stopped its search. This was because Malaysian officials did not share enough information. China urged Malaysia to be more open.

Malaysia first refused to share military radar data. They called it "too sensitive." But they later agreed. Experts said sharing radar data could reveal military capabilities. Some countries might have had radar data but did not want to share it.

Criticism also focused on delays in the search. On March 11, 2014, a British satellite company, Inmarsat, had data. It suggested the plane was not where they were searching. It might have flown south or north. This information was not made public until March 15. Malaysia Airlines said the satellite signals needed to be checked and understood first.

In June 2014, families of passengers started a crowdfunding campaign. They wanted to raise money as a reward for anyone with information about Flight 370. The campaign raised over US$100,000.

Malaysia Airlines

A month after the disappearance, Malaysia Airlines' chief executive said ticket sales had dropped. This was partly because the airline stopped its ads. He said the airline's main focus was to care for the families. He also said the airline had enough insurance to cover the financial loss. In China, bookings on Malaysia Airlines were down 60% in March.

Malaysia Airlines stopped using the flight number MH370. It was replaced with MH318. This is common after major accidents. Flight 318 was later stopped due to low demand.

Malaysia Airlines received US$110 million from insurers in March 2014. This was for initial payments to families and search costs. By May, the total insured loss was about US$350 million.

Financial Problems

Malaysia Airlines was already struggling financially. It was trying to cut costs to compete with new, cheaper airlines. The airline had lost money for three years in a row. It lost more money in the first and second quarters of 2014. Industry experts expected the airline to lose more customers.

Many thought Malaysia Airlines needed to change its image or get government help. The loss of Flight 17 made its financial problems much worse. The government's investment arm, Khazanah Nasional, bought the rest of the airline. This made it a state-owned company again on September 1, 2015.

Compensation for Families

The lack of evidence about the cause of the disappearance raised questions about insurance payments. Under the Montreal Convention, the airline is responsible. Each passenger's family is automatically entitled to about US$175,000 from the airline's insurance. This totals almost US$40 million for the 227 passengers.

Malaysia Airlines also faced lawsuits from families. Compensation could vary depending on where the lawsuit was filed. An American court might award US$8–10 million. Chinese courts would likely award much less. Malaysia officially declared Flight 370 an accident on January 29, 2015. This allowed compensation claims to be made. The first lawsuit was filed in October 2014 by two Malaysian boys. They sued for negligence and breach of contract. Other lawsuits were filed in China and Malaysia.

Malaysia Airlines offered "comfort money" to families. In China, families were offered about US$5,000. Some rejected this offer. Malaysian relatives reportedly received only US$2,000. In June 2014, Malaysia said seven families received US$50,000 in advance. Full payment would come after the plane was found or declared lost.

Malaysia's Response

Before 2016

Air force experts and the Malaysian opposition questioned Malaysia's air force and radar. Many criticized the Royal Malaysian Air Force for not reacting to the unknown plane (Flight 370) flying through Malaysian airspace. The military only realized this after checking radar recordings hours later. This was a security failure and a missed chance to stop Flight 370.

Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak said mistakes were made. But he said Malaysia had done its best to coordinate the search. He stressed that the aviation industry must learn from MH370.

Opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim criticized the government's response. He called for an international committee to lead the investigation. He said this would "save the image of the country." Malaysian authorities accused Anwar of making the crisis political. The captain of Flight 370 was a supporter of Anwar.

When asked why Malaysia did not send fighter jets, the acting Transport Minister said it was a commercial plane and not hostile. He said, "If you're not going to shoot it down, what's the point of sending [a fighter jet] up?" A former air force pilot said no pilots were at the base at night. So, the plane could not have been stopped.

The crisis response showed problems with media in Malaysia. After years of strict media control, officials were not used to being questioned. Malaysia struggled to adapt to demands for openness.

March 2020

On March 8, 2020, six years after the disappearance, two memorial events were held. Families of MH370 passengers asked for a new search. Malaysia's former Transport Minister expressed regret about not being able to discuss compensation documents with the government. Families hoped the new Transport Minister could speed up compensation.

Malaysia's transport ministry secretary-general said he asked to meet the Prime Minister. He wanted to present a paper on compensation for families. The ministry would also keep asking the new government to restart the search.

China's Response

Chinese Deputy Foreign Minister Xie Hangsheng was doubtful about Malaysia's conclusion. He demanded "all the relevant information and evidence" about the satellite data. He said Malaysia must "finish all the work including search and rescue." The next day, Chinese president Xi Jinping sent an envoy to Kuala Lumpur.

Passengers' Relatives

In the days after the disappearance, families of Chinese passengers became very frustrated. On March 25, 2014, about 200 family members protested outside the Malaysian embassy in Beijing. Relatives in Kuala Lumpur also protested. They accused Malaysia of hiding the truth. They wanted an apology for the poor handling of the disaster.

A Chinese newspaper said Malaysia was not entirely to blame for the "bizarre" crisis. It asked Chinese relatives not to let emotions rule. The Chinese ambassador to Malaysia defended Malaysia's government. He said the relatives' "radical and irresponsible opinions" did not represent China. He also criticized Western media for spreading "false news" and "rumours." A US official criticized China for giving false leads.

In July 2019, Beijing-based families were told Malaysia Airlines would stop "Meet the Families" sessions. This was after about 50 sessions.

Boycotts

Some Chinese citizens boycotted Malaysian things, like holidays and singers. This was to protest Malaysia's handling of the investigation. Bookings on Malaysia Airlines from China dropped by 60% in March. Several Chinese ticketing agencies stopped selling tickets to Malaysia. Large Chinese travel agencies reported a 50% drop in tourists. China was the third-largest source of visitors to Malaysia before Flight 370 disappeared.

Celebrities largely led or supported the boycotts. Film star Chen Kun posted on Weibo (a Chinese social media site) that he would boycott Malaysia. His post was shared over 70,000 times.

China and Malaysia had named 2014 the "Malaysia–China Friendship Year." This was to celebrate 40 years of diplomatic relations.

Air Transport Industry Changes

The fact that a modern plane could disappear surprised many. Changes in aviation usually take years. But airlines and authorities quickly took action to prevent similar incidents.

Aircraft Tracking

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) and the ICAO started working on new ways to track planes in real time. The IATA created a task force to set requirements for tracking systems. This would let airlines choose the best solution. The task force aimed to find ways to provide information quickly for search, rescue, and recovery. In December 2014, the IATA task force suggested airlines track planes every 15 minutes. The ICAO can set standards, but countries must adopt them.

In 2016, the ICAO adopted a rule that by November 2018, all planes over the ocean must report their position every 15 minutes. In March, the ICAO approved a change. New planes made after January 1, 2021, must have tracking devices. These devices must send location info at least once per minute in an emergency.

In May 2014, Inmarsat offered its tracking service for free to planes with an Inmarsat satellite connection. Inmarsat also changed how often its systems "shake hands" with planes from one hour to 15 minutes.

Transponders

After the September 11 attacks, there was a call for automatic transponders. But no changes were made. Aviation experts preferred flexible control in case of problems. After Flight 370, the industry still resisted automatic transponders. This was due to high costs. Pilots also opposed changes, saying they needed to cut power in a fire. However, new tamper-proof circuit breakers were considered.

Flight Recorders

The urgent search for flight recorders in April 2014 highlighted their limits. Their batteries only last 30 days. The signal can only be detected within 2,000-3,000 meters (6,600-9,800 ft). Even if found, the cockpit voice recorder only stores two hours of data. This means events leading to Flight 370 diverting happened more than two hours before the flight ended.

After Air France Flight 447 in 2009, there was a call to increase ULB battery life. But it was not until 2014 that the ICAO made this recommendation. The European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) now requires ULB transmitting time to increase from 30 to 90 days by January 1, 2020. They also suggested new ULBs with a greater range for planes flying over oceans.

In March 2016, the ICAO made changes to address issues from Flight 370. For planes made after 2020, cockpit voice recorders must record at least 25 hours of data. This ensures all parts of a flight are recorded. New plane designs approved after 2020 must have a way to recover flight recorders, or their data, before they sink. This can be done by streaming data or using recorders that eject and float. These new rules do not require changes to existing planes.

Safety Recommendations

In January 2015, the US National Transportation Safety Board mentioned Flight 370 and Air France Flight 447. It issued eight safety recommendations for finding plane wreckage in remote or underwater areas. It also repeated calls for cockpit image recorders and tamper-resistant flight recorders and transponders.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Vuelo 370 de Malaysia Airlines para niños

In Spanish: Vuelo 370 de Malaysia Airlines para niños

- List of accidents and incidents involving commercial aircraft

- List of missing aircraft

- List of people who disappeared mysteriously at sea

- List of unrecovered flight recorders

- List of unsolved deaths