Thomas Babington Macaulay facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Lord Macaulay

|

|

|---|---|

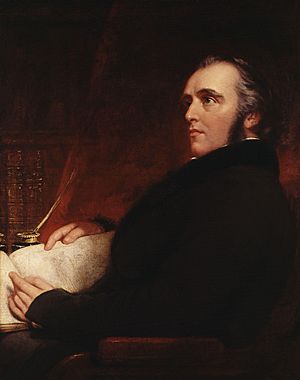

Photogravure of Macaulay by Antoine Claudet

|

|

| Secretary at War | |

| In office 27 September 1839 – 30 August 1841 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Prime Minister | The Viscount Melbourne |

| Preceded by | Viscount Howick |

| Succeeded by | Sir Henry Hardinge |

| Paymaster-General | |

| In office 7 July 1846 – 8 May 1848 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Prime Minister | Lord John Russell |

| Preceded by | Hon. Bingham Baring |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Granville |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 25 October 1800 Leicestershire, England |

| Died | 28 December 1859 (aged 59) London, England |

| Political party | Whig |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Occupation | Politician |

| Profession | Historian |

| Signature | |

Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay (born October 25, 1800 – died December 28, 1859), was a famous British historian and a Whig politician. He held important government jobs, serving as the Secretary at War from 1839 to 1841 and as the Paymaster-General from 1846 to 1848.

Macaulay is best known for his book, The History of England. In this book, he wrote about his belief that Western European culture was superior and that its social and political progress was bound to happen. His work is a key example of a type of history writing called Whig history, and people still admire his writing style today.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Macaulay was born on October 25, 1800, in Rothley Temple, Leicestershire, England. His father, Zachary Macaulay, was a Scottish man who became a colonial governor and worked to end slavery. His mother, Selina Mills, was from Bristol.

Even as a young child, Thomas was very smart. There's a story that when he was a toddler, he looked at factory chimneys and asked his father if the smoke came from the fires of hell!

He went to a private school in Hertfordshire and then to Trinity College, Cambridge. At Cambridge, he won several awards, including a gold medal in 1821. In 1825, he wrote an important essay about the poet John Milton for the Edinburgh Review magazine.

Macaulay was a great learner. He taught himself German, Dutch, and Spanish, and he was fluent in French. He also studied law and became a lawyer in 1826, but he was more interested in a career in politics.

Thomas Babington Macaulay never married or had children. He was very close to his younger sisters, Margaret and Hannah. He was also very fond of Hannah's daughter, Margaret, whom he called 'Baba'.

Time in India (1834–1838)

In 1830, Macaulay became a Member of Parliament (MP) for a small area called Calne. His first speech in Parliament was about giving Jewish people more rights in the UK. His speeches supporting changes to Parliament were highly praised.

After the Reform Act 1832 was passed, he became an MP for Leeds. This law changed how areas were represented in Parliament.

In 1833, Macaulay needed a job that paid more money because his father was struggling financially. He resigned from Parliament and accepted a role as the first Law Member of the Governor-General's Council. He moved to India in 1834 and served there until 1838.

His most famous contribution in India was his Minute on Indian Education in February 1835. This document was key to bringing Western-style education to India.

Macaulay suggested that English should become the official language for secondary education in India. He believed that training English-speaking Indians as teachers would be beneficial. He famously wrote that "a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia." He thought European books were much better for learning facts and general principles.

He argued that Indian languages like Sanskrit and Persian were not easily understood by everyone. He believed that English was no harder to learn than these languages for most Indians. So, he suggested that from the sixth year of schooling onwards, students should learn European subjects with English as the teaching language.

The Governor-General of India, Lord William Bentinck, agreed with Macaulay's ideas. The English Education Act of 1835 followed Macaulay's suggestions closely.

During his last years in India, Macaulay worked on creating a new set of laws for crimes, known as the Indian Penal Code. This code was put into effect in 1860, after the Indian Mutiny of 1857. This code, and others that followed, became the basis for criminal law in many other British colonies around the world, including Pakistan, Malaysia, Nigeria, and India itself.

In Indian culture, the term "Macaulay's Children" is sometimes used to describe people of Indian background who adopt Western culture. This term can be used negatively, suggesting disloyalty to one's own heritage. However, some people, like those from the Dalit community in India, have seen Macaulay's ideas about Western education as a way to empower themselves.

Return to British Public Life (1838–1857)

Macaulay returned to Britain in 1838. The next year, he became an MP for Edinburgh. In 1839, Lord Melbourne made him Secretary at War, and he joined the Privy Council, a group of advisors to the monarch.

In 1841, Macaulay spoke about copyright law. His ideas, with some small changes, became the foundation of copyright law in English-speaking countries for many years. He argued that copyright is a type of monopoly, which generally has negative effects on society.

After Lord Melbourne's government fell in 1841, Macaulay spent more time on his writing. He returned to government in 1846 as Paymaster-General under Lord John Russell.

In the 1847 election, he lost his seat in Edinburgh. He believed this was because religious groups were upset about his speech supporting government funding for Maynooth College in Ireland, which trained Catholic priests.

In 1852, the people of Edinburgh asked him to be their MP again. He agreed, but only if he didn't have to campaign and didn't have to promise to take a side on any political issue. Surprisingly, he was elected on these terms! He didn't attend Parliament often because of poor health. He resigned from his seat in January 1856.

In 1857, he was given the title of Baron Macaulay, which made him a member of the peerage and allowed him to sit in the House of Lords. However, he rarely attended meetings there.

Later Life and Death (1857–1859)

Macaulay was part of a committee that decided which historical events should be painted in the new Palace of Westminster. This project helped lead to the creation of the National Portrait Gallery in London, which opened in 1856. Macaulay was one of its first trustees.

In his final years, his health made it harder for him to work. He died of a heart attack on December 28, 1859, at the age of 59. His most important work, The History of England from the Accession of James the Second, was not finished when he died.

On January 9, 1860, he was buried in Westminster Abbey, in a section called Poets' Corner. Since he had no children, his title of Baron ended when he died.

His nephew, Sir George Trevelyan, later wrote a book about Macaulay's life and letters.

Literary Works

As a young man, Macaulay wrote poems called Ivry and The Armada. He later included these in Lays of Ancient Rome, a very popular collection of poems about heroic stories from Roman history. He started writing these poems in India and finished them in Rome, publishing them in 1842. The most famous poem in the collection is Horatius, which tells the story of the brave Horatius Cocles. It includes these famous lines:

Then out spake brave Horatius,

The Captain of the Gate:

"To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his gods?"

His essays, which were first published in the Edinburgh Review, were collected into a book called Critical and Historical Essays in 1843.

Historian and Writer

In the 1840s, Macaulay began his most famous work, The History of England from the Accession of James the Second. The first two volumes were published in 1848. He had planned to write about English history up to the reign of King George III, but later decided to finish with the death of Queen Anne in 1714.

The third and fourth volumes, which covered history up to the Peace of Ryswick, were published in 1855. When he died in 1859, he was working on the fifth volume. His sister, Lady Trevelyan, prepared this final volume for publication after his death.

Macaulay's historical writings are known for their strong language and their confident belief in a progressive view of British history. He saw British history as a journey where the country moved away from old superstitions and unfair rule to create a balanced government and a forward-thinking culture with freedom of belief. This idea of human progress is called the Whig interpretation of history.

Some later historians have criticized Macaulay's approach for being one-sided. He sometimes presented people he disagreed with as villains and those he admired as heroes. For example, he worked hard to show that his hero, William III, was not responsible for the Glencoe massacre.

Legacy and Influence

Many people admired Macaulay's work. The historian Lord Acton read Macaulay's History of England four times and called him "the most representative Englishman then living."

Even though some historians have pointed out flaws in his work, Macaulay's History of England is still respected. It was based on a huge amount of research. One historian, W. A. Speck, noted that Macaulay "took pains to present the virtues even of a rogue, and he painted the virtuous warts and all," meaning he tried to show both the good and bad sides of people.

Another historian, Piers Brendon, called Macaulay "the only British rival to Gibbon," referring to the famous historian Edward Gibbon. In 1972, J. R. Western wrote that "Despite its age and blemishes, Macaulay's History of England has still to be superseded by a full-scale modern history of the period."

Works

- Lays of Ancient Rome (1842)

- Macaulay, Thomas Babington (1848).

The History of England from the Accession of James II. Philadelphia: Porter & Coates. Wikisource.

The History of England from the Accession of James II. Philadelphia: Porter & Coates. Wikisource.

- 5 vols (1848): Vol 1, Vol 2, Vol 3, Vol 4, Vol 5 at Internet Archive

- 5 vols (1848): Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Vol. 3, Vol. 4, Vol. 5 at Project Gutenberg

- Critical and Historical Essays (1843), 2 vols, edited by Alexander James Grieve. Vol. 1, Vol. 2

- Macaulay, Thomas Babington Baron Macaulay (1881). Lays of Ancient Rome: With Ivry, and The Armada. Longmans, Green, and Company. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.182206.

- The Miscellaneous Writings and Speeches of Lord Macaulay (1860), 4 vols Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Vol. 3, Vol. 4

- Lays of Ancient Rome (Complete) at Poets' Corner

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Thomas Macaulay para niños

In Spanish: Thomas Macaulay para niños

- Philosophic Whigs

- Whig history further explains the interpretation of history that Macaulay espoused.

- Samuel Rogers#Middle life and friendships