Whigs (British political party) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Whigs

|

|

|---|---|

| Leader(s) | |

| Founder | Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury |

| Founded | 1678 |

| Dissolved | 1859 |

| Merged into | Liberal Party |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Centre to centre-left |

| Religion | Protestantism |

| Colours | Orange |

The Whigs were an important political group in the Parliaments of England, Scotland, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom. They were active from the 1680s until the 1850s. During this time, they often competed for power with their main rivals, the Tories. The Whigs later joined with other groups like the Peelites and Radicals to form the Liberal Party in the 1850s. Some Whigs later left the Liberal Party in 1886. They helped create the Liberal Unionist Party, which then merged with the Conservative Party in 1912.

The Whigs started as a group that was against a king having total power (absolute monarchy). They also opposed giving full rights to Catholics (Catholic Emancipation). Instead, they supported a monarchy where the king's power was limited by a parliament. They played a big part in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. This event removed the Catholic Stuart kings from the throne.

After George I became king in 1714, the Whigs gained strong control. This period (1714–1760) is known as the Whig Supremacy. They removed Tories from important government jobs, the army, and the Church of England. Robert Walpole was a key Whig leader. He led the government from 1721 to 1742. Great Britain was mostly run by the Whigs until King George III became king in 1760. He allowed Tories back into government. Still, the Whigs remained powerful for many years. Historians call the time from about 1714 to 1783 the "long period of Whig oligarchy." This means a small group of Whigs held most of the power.

By 1784, both the Whigs and Tories became more formal political parties. Charles James Fox led the Whigs against the new Tory party, led by William Pitt the Younger. These parties relied on rich politicians for support, not just popular votes. Even though there were elections, only a few powerful men controlled most voters.

Over the 18th century, the parties changed. At first, Whigs generally supported rich families (the aristocracy). They also supported Protestants who were not part of the Church of England. Tories, however, favored smaller landowners and a strong Church of England. Later, Whigs gained support from new industrial leaders and business people. Tories found support among farmers, landowners, and those who favored spending on the military.

By the early 1800s, the Whigs wanted several key changes. They believed Parliament should have the most power. They supported free trade and ending slavery. They also wanted to expand who could vote. And they pushed for full equal rights for Catholics. This was a big change from their earlier anti-Catholic views.

What's in a Name?

The word Whig first came from whiggamore. This was a term used in northern England for cattle drivers from western Scotland. These drivers would shout "Chuig" or "Chuig an bothar," meaning "away" or "to the road." English people heard this as "Whig." They used "Whig" or "Whiggamore" to make fun of these Scottish cattle drivers.

During the English Civil Wars, the English started using "Whig" to describe a radical group of Scottish Covenanters. These Covenanters were against the king's church rules in Scotland.

The term Whig became part of English politics during the Exclusion Bill crisis (1678–1681). People argued if King Charles II's Catholic brother, James, Duke of York, should become king. Those who wanted to stop James from becoming king were called "Whigs." It was a rude name for them.

David Hume, a historian, wrote in 1760 that the king's supporters called their opponents "Whigs." This was because they were like the Scottish religious rebels. The opponents called the king's supporters "Tories." This was because they were like Irish Catholic criminals. These names, though silly at first, became common.

How the Whigs Started

The Exclusion Crisis

Under Lord Shaftesbury, the Whigs in Parliament wanted to stop James, Duke of York, from becoming king. They worried because he was Catholic. They also feared he would try to rule with total power. The Whigs believed a Catholic king would threaten Protestant religion, freedom, and property.

The first bill to exclude James passed easily in May 1679. King Charles II then closed Parliament. But new elections showed the Whigs were even stronger. Charles tried to wait for things to calm down. When Parliament met again in October 1680, another Exclusion Bill passed. But the House of Lords rejected it. Charles dissolved Parliament again in January 1681. The Whigs still did well in the next election.

The next Parliament met briefly in Oxford in March. Charles quickly dissolved it again. He decided to rule without Parliament. He also made a deal with the French King Louis XIV for support against the Whigs. Without Parliament, the Whigs slowly lost power. The government also cracked down on them after the Rye House Plot was discovered. Many Whig leaders, like Lord Shaftesbury and the Duke of Monmouth, fled to the Netherlands. Others were executed for treason.

The Glorious Revolution

After the Glorious Revolution in 1688, Queen Mary II and King William III ruled. They worked with both Whigs and Tories. Many Tories still supported the old king, James II. William saw that Tories were generally more friendly to royal power than Whigs. So he used both groups in his government.

At first, his government was mostly Tory. But soon, a group of younger Whig politicians, called the Junto Whigs, became very powerful. They were well-organized. This made some other Whigs, called Country Whigs, unhappy. They felt the Junto Whigs were giving up their beliefs for power. These Country Whigs slowly joined with the Tory opposition in the late 1690s.

Whig History

The 18th Century

When Queen Anne became queen, she favored the Tories. She removed the Junto Whigs from power. But after a short time with only Tory leaders, she went back to balancing the parties. Her moderate Tory ministers, the Duke of Marlborough and Lord Godolphin, supported this.

However, the War of the Spanish Succession became unpopular with the Tories. Marlborough and Godolphin had to rely more on the Junto Whigs. By 1708, the Junto Whigs controlled the government. Queen Anne became uncomfortable with this. Her relationship with the Duchess of Marlborough also got worse. Many non-Junto Whigs also felt uneasy. They started working with Robert Harley's Tories. In 1710, Anne dismissed Godolphin and the Junto ministers. She replaced them with Tories.

The Whigs then became the opposition. They strongly criticized the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht. They tried to stop it in the House of Lords. But the Tory government convinced the Queen to create twelve new Tory peers. This allowed the treaty to pass.

Whig Ideas

The Whigs mainly believed that Parliament should be supreme. They also wanted religious freedom for Protestant groups who were not part of the Church of England. They were strongly against a Catholic king. They saw the Catholic Church as a threat to freedom. Pitt the Elder called the "errors of Rome" a "subversion of all civil as well as religious liberty."

The ideas of John Locke, a famous thinker, greatly influenced the Whigs. They used his ideas about universal rights. Later, in the 1770s, the ideas of Adam Smith, who helped create classical liberalism, became important. Smith's theories fit well with the Whig Party's liberal views.

Samuel Johnson, a well-known writer, often criticized the Whigs. He defined a Tory as someone who supports the old ways of the state and the Church of England, "opposed to a Whig." He thought 18th-century Whigs were like 17th-century Puritans. He believed they were against the established order of church and state.

Trade Policies

When they first started, the Whigs supported protectionism. This meant they wanted to protect local businesses by limiting imports. They were against free trade. They also opposed the pro-French policies of Kings Charles II and James II. They believed an alliance with Catholic France would harm English freedom and Protestantism. The Whigs argued that trade with France was bad for England. They thought it would make France rich at England's expense.

In 1678, the Whigs passed a law that banned certain French goods. This was a key moment for Whig trade policy. King James II later removed this law. But when William III became king in 1688, a new law banned French goods again. In 1704, the Whigs passed another law to protect against French imports.

In 1710, Queen Anne appointed a Tory government that favored free trade. In 1713, a Tory minister proposed a trade agreement with France. This would have led to freer trade. But the Whigs strongly opposed it, and it was stopped.

In 1786, William Pitt the Younger's government made a trade treaty with France. This led to freer trade. But all the Whig leaders attacked it. They used their traditional anti-French and protectionist arguments. Charles James Fox said France was England's natural enemy. He believed France could only grow at Britain's expense.

Historians have noted that the Whig party's policy, from before 1688 until Fox's time, was very protectionist. This early Whig protectionism is sometimes used today by economists who question modern free trade ideas.

Later, some Whigs opposed the protectionist Corn Laws. But trade limits were not removed even when Whigs returned to power in the 1830s.

Whig Supremacy

When George Louis of Hanover became king in 1714, the Whigs returned to power. The Jacobite rising of 1715, a rebellion by Tories who supported the old king, made the Tory party look bad. The Septennial Act 1716 also helped the Whigs. It made elections happen every seven years instead of three. This helped the Whigs stay in power longer.

Between 1717 and 1720, the Whig party split. Government Whigs, led by James Stanhope, were opposed by Robert Walpole. Stanhope had the king's support. But Walpole was closer to the Prince of Wales. Walpole later returned to government. He successfully defended the government when the South Sea Bubble collapsed. When Stanhope died in 1721, Walpole became the leader of the government. He is known as Britain's first Prime Minister. In the 1722 election, the Whigs won a huge victory.

From 1714 to 1760, the Tories struggled. But they still had many members in the House of Commons. The governments of Walpole, Henry Pelham, and the Duke of Newcastle dominated this period. These leaders always called themselves "Whigs."

George III's Reign

Things changed when George III became king. He wanted to increase his own power. He wanted to be free from the influence of the powerful Whig families. So, George promoted his old teacher, Lord Bute. This broke the power of the old Whig leaders.

For ten years, there was political chaos. Different Whig groups took turns in power. They all called themselves "Whigs." Then, a new system appeared with two opposition groups. The Rockingham Whigs claimed to be the true followers of the old Whig traditions. They had thinkers like Edmund Burke supporting them. The other group followed Lord Chatham. He was a hero from the Seven Years' War. He generally opposed political parties.

The Whigs opposed the government of Lord North. They called it a Tory government. Lord North's government included people who had been Whigs. But it also had people who were seen as leaning towards the Tories.

American Influence

The idea that Lord North's government was Tory also influenced the American colonies. Writings by British political writers, known as the Radical Whigs, helped inspire American republican ideas. Early activists in the colonies called themselves Whigs. They saw themselves as allies with the political opposition in Britain. Later, when they sought independence, they started calling themselves Patriots. Americans who supported the king were called Tories.

Later, the United States Whig Party was formed in 1833. They opposed a strong president, like Andrew Jackson. This was similar to how British Whigs opposed a strong king. The True Whig Party in Liberia was named after the American party.

Two-Party System

Historians agree that the Tory party declined in the 1740s and 1750s. It stopped being an organized party by 1760. For a while, there were no organized political parties in Parliament. Instead, different political groups competed. They all claimed to have Whiggish views.

Lord North's government fell in March 1782 after the American Revolution. A new government formed. It was a mix of the Rockingham Whigs and followers of Lord Chatham. After Rockingham died, this group split. Charles James Fox left the government. The next government was short-lived. Fox returned to power in April 1783. This time, he formed an unexpected alliance with his old enemy, Lord North.

This alliance seemed strange to many. But it lasted until December 1783. King George III and the House of Lords brought down the alliance. The King then made William Pitt the Younger his prime minister.

It was around this time that a true two-party system began to appear. Pitt and the government were on one side. The Fox-North alliance was on the other. Fox said he claimed "a monopoly of Whig principles." Pitt often called himself an independent Whig. He generally opposed a strict party system. Fox's supporters saw themselves as the true heirs of the Whig tradition. They strongly opposed Pitt in his early years. For example, they supported the Prince of Wales getting full power as regent when the King was temporarily ill.

The Whigs in opposition split over the French Revolution. Fox and some younger members, like Charles Grey, supported the French revolutionaries. But others, led by Edmund Burke, were strongly against them. Burke himself joined Pitt in 1791. Many other Whigs also felt uncomfortable with Fox's support for radical ideas. They split from Fox in early 1793 over the war with France. By the next summer, many had joined Pitt's government.

The 19th Century

Many Whigs who had joined Pitt eventually returned to the party. They rejoined Fox in the Ministry of All the Talents after Pitt's death in 1806. Pitt's followers, however, refused to be called Tories. They preferred "The Friends of Mr. Pitt." After the Talents ministry fell in 1807, the Foxite Whigs were out of power for about 25 years. Even when Fox's old ally, the Prince of Wales, became regent in 1811, it didn't change things. The Prince had completely broken with his old Whig friends. The government of Lord Liverpool (1812–1827) also called themselves Whigs.

Party Structure and Appeal

By 1815, the Whigs were not yet a "party" in the modern sense. They didn't have a clear program or policy. They were not even fully united. Generally, they wanted to reduce the king's power to give out jobs. They also supported nonconformists and the interests of merchants and bankers. They also leaned towards reforming the voting system. Most Whig leaders were still rich landowners. A notable exception was Henry Brougham, a talented lawyer from a more modest background.

Historians suggest that Whig leaders welcomed more middle-class people joining politics after 1815. This new support strengthened their position in Parliament. Whigs rejected the Tory idea of strong government control. They expanded political discussions beyond Parliament. Whigs used newspapers, magazines, and local clubs to share their message. The press organized petitions and debates. They also reported on government policy to the public. Leaders like Henry Brougham built alliances with people who couldn't vote directly. This new approach helped define Whiggism. It also paved the way for their future success. Whigs forced the government to listen to public opinion. They influenced ideas about representation and reform throughout the 19th century.

Return to Power

Whigs reunited by supporting moral reforms. A key one was ending slavery. They won in 1830 as champions of Parliamentary reform. Lord Grey became prime minister (1830–1834). The Reform Act 1832, championed by Grey, was their most important achievement. It expanded who could vote. It ended the system of "rotten and pocket boroughs" where powerful families controlled elections. Instead, power was given based on population. It added 217,000 voters in England and Wales. Only upper and middle classes could vote. This shifted power from rich landowners to city middle classes.

In 1832, the party ended slavery in the British Empire with the Slavery Abolition Act 1833. They bought and freed enslaved people, especially in the Caribbean sugar islands. After investigations showed the terrible conditions of child labor, limited reforms were passed in 1833. The Whigs also passed the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834. This law changed how aid was given to the poor.

Around this time, the Whig historian Thomas Babington Macaulay began to promote the Whig view of history. This view saw all of English history as leading up to Lord Grey's reform bill. This view sometimes distorted how 17th and 18th-century history was seen. Macaulay tried to fit the complex politics of the past into the clear party divisions of the 19th century.

In 1836, the Reform Club was built in London. It was a private club for gentlemen. It was a result of the successful Reform Act 1832. Edward Ellice Sr., a Whig Member of Parliament, founded the club. He was rich from the Hudson's Bay Company. But he was very dedicated to passing the Reform Act. This new club was for members of both Houses of Parliament. It was meant to be a place for the radical ideas that the Reform Bill represented. It became a center for liberal and progressive thought. It was closely linked to the Liberal Party, which largely replaced the Whigs later in the 19th century.

Until the Liberal Party declined in the early 1900s, Liberal MPs and peers were expected to be members of the Reform Club. It was seen as an unofficial party headquarters. However, in 1882, the National Liberal Club was created. It was meant to be more "inclusive" for Liberal leaders and activists across the United Kingdom.

Becoming the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party (officially named in 1868) grew from a mix of Whigs, free trade Tories who followed Robert Peel, and free trade Radicals. This group first formed under the Peelite Earl of Aberdeen in 1852. It became more permanent under the former Canningite Tory Lord Palmerston in 1859.

At first, the Whigs were the most important part of this new group. But the Whig influence in the new party slowly decreased. This happened during the long leadership of former Peelite William Ewart Gladstone. Later, most of the old Whig aristocracy left the party in 1886. This was over the issue of Irish home rule. They helped form the Liberal Unionist Party. This party then merged with the Conservative Party by 1912. However, the Unionists' support for trade protection in the early 1900s further pushed away the more traditional Whigs. By the early 20th century, "Whiggery" was largely gone. One of the last politicians to celebrate his Whig roots was Henry James.

See also

In Spanish: Whig para niños

In Spanish: Whig para niños

- Early-18th-century Whig plots

- Foxite

- King of Clubs (Whig club)

- Kingdom of Great Britain

- List of United Kingdom Whig and allied party leaders (1801–1859)

- Patriot Whigs

- Whig government

- Whig party (United States)

Images for kids

-

Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, painted more than once during his chancellorship in 1672 by John Greenhill

-

Equestrian portrait of William III by Jan Wyck, commemorating the landing at Brixham, Torbay, 5 November 1688

-

A c. 1705 portrait of John Somers, 1st Baron Somers by Godfrey Kneller.

-

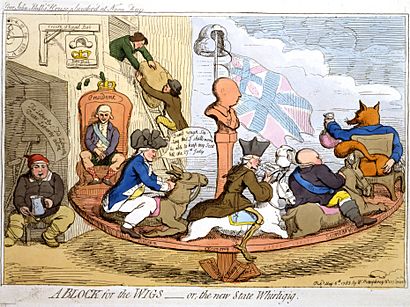

In A Block for the Wigs (1783), caricaturist James Gillray caricatured Charles James Fox's return to power in a coalition with Frederick North, Lord North (George III is the blockhead in the centre)