Rye House Plot facts for kids

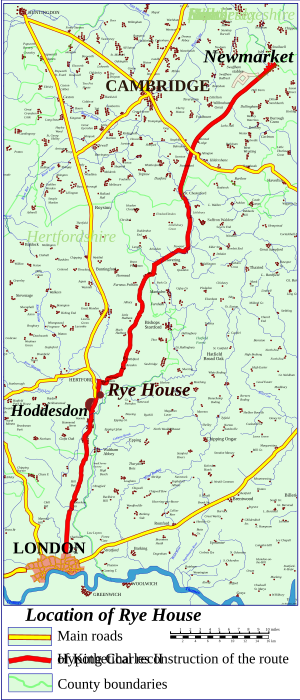

The Rye House Plot was a secret plan in 1683 to attack King Charles II of England and his brother, James, Duke of York, who was next in line to become king. The royal brothers were traveling from Westminster to Newmarket to watch horse races. They were expected to return to London on April 1, 1683. However, a big fire broke out in Newmarket on March 22, destroying half the town. Because of the fire, the races were canceled, and the King and Duke returned to London earlier than planned. This meant the secret attack never happened.

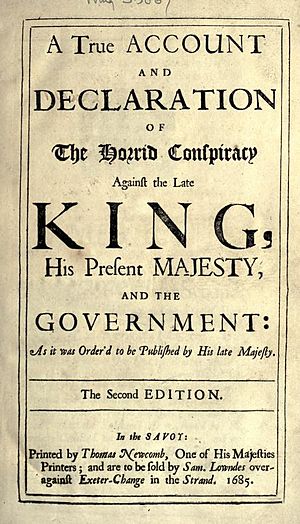

Historians still discuss how much of the plot was fully planned out. Even if the assassination part wasn't complete, some leaders who opposed the Stuart monarchy were definitely thinking about starting a rebellion in England. The government reacted strongly, holding many trials and searching widely for weapons. The Plot came before, and might have sped up, the rebellions of 1685, known as the Monmouth Rebellion and Argyll's Rising.

Contents

Why Did People Plot Against the King?

After the monarchy was brought back with Charles II in 1660, some members of Parliament, former republicans, and many Protestant people in England were worried. They thought the King was too close to France's Louis XIV and other Catholic rulers in Europe. Many people disliked Catholics, linking them to a type of rule called absolutism, where the king has total power. People were especially concerned about who would become king next. While Charles was publicly Anglican (part of the Church of England), both he and his brother were known to have Catholic sympathies. These worries grew stronger in 1673 when James was found to have become a Roman Catholic.

In 1681, a made-up story called the Popish Plot caused a lot of fear. Because of this, a law called the Exclusion Bill was suggested in Parliament. This bill would have stopped James from becoming king. But King Charles was smarter than his opponents and closed down the Oxford Parliament. This left his opponents with no legal way to stop James from becoming king. Soon, rumors of secret plans and plots were everywhere. The group that opposed the King, often called the "country party," was in disarray. Leaders like Lord Melville, Lord Leven, and Lord Shaftesbury (who led the opposition) fled to Holland, where Shaftesbury soon died. Many well-known members of Parliament and noblemen from the "country party" later became known as Whigs, a name that stuck for a long time.

The Secret Plan at Rye House

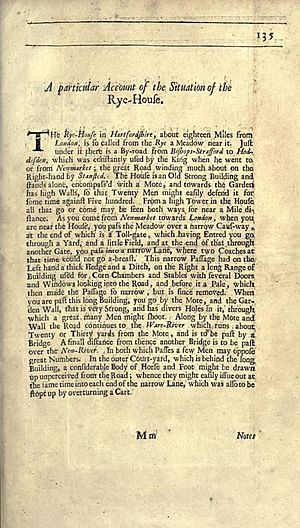

Rye House was an old, strong house with a moat around it, located north-east of Hoddesdon, Hertfordshire. The house was rented by Richard Rumbold, a republican and former soldier from the Civil War. The plan was to hide a group of men on the property and ambush the King and the Duke as they passed by on their way back to London from the horse races at Newmarket. The "Rye House plotters," an extreme group of Whigs named after this plot, supposedly chose this plan because it offered good hiding spots and could be done with a small group using guns from a safe distance.

The royal party was expected to travel on April 1, 1683. However, a big fire happened in Newmarket on March 22, destroying half the town. The races were canceled, and the King and the Duke returned to London early. Because of this, the planned attack never took place.

Who Were the Plotters?

Many people were involved in secret plans during this time. From the early 1680s, people on what became the Whig side of British politics often discussed some kind of armed resistance. It wasn't clear what form this resistance would take. There were talks about taking control of cities like Bristol (not just London) and even a Scottish uprising. How the Plot has been written about since then has often been biased. Scholars are still trying to figure out exactly who was deeply involved in planning violent and revolutionary actions.

The West Cabal

The plan to attack the King was centered around a group that met in 1682–1683. This group was led by Robert West, a lawyer and member of the Green Ribbon Club. This group is now often called the Rye House cabal. West had been involved in some cases related to the Popish Plot accusations. Through this, he met Aaron Smith and William Hone, who also became plotters, though they were separate from the main group.

John Wildman introduced Rumbold to West's group. But when the plot was discovered, both Wildman and Rumbold had stepped back. Wildman refused to pay for Rumbold to buy weapons, and Rumbold had lost his earlier excitement.

Plans for an Uprising

Some members of West's group, like Richard Nelthorpe, preferred a rebellion instead of an assassination. This connected many of West's group discussions with the plans of Algernon Sidney and other more important members of the "country party," known as the Monmouth cabal. In September 1682, the group around Monmouth also discussed an uprising, and some people were involved in both groups. This "cabal" later became known as the "council of six." A key part of their plan was to get Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll to lead a military rebellion in Scotland. In January 1683, Smith was sent to contact supporters in Scotland for the "six," hoping to bring them to London. But he reportedly messed up the mission by talking too much.

In fact, West's connections with the Monmouth cabal and his knowledge of their plans were sometimes indirect. Thomas Walcot and Robert Ferguson had gone with Shaftesbury to the Netherlands when he left England in November 1682. They both then returned to London and met with West. West learned from Walcott about Shaftesbury's own plan for a general rebellion. Walcott even said he would lead the attack on the royal guards, but he, like others, drew the line at assassination. In the spring of 1683, there were more talks between the Monmouth cabal and West's group about writing a public statement. This happened through Sir Thomas Armstrong especially. They disagreed about whether a republic (where people elect leaders) or a monarchy (where a king rules) should be the result of their revolutionary actions. In May 1683, West and Walcott discussed with a larger group the chances of gathering several thousand men around London.

Informers and Arrests

News of the plot became public when Josiah Keeling told Sir Leoline Jenkins about it on June 12, 1683. Keeling had contacted a court official, who connected him with George Legge, 1st Baron Dartmouth. Dartmouth then brought him to Jenkins, who was a Secretary of State. Keeling's statements were used in the trials of Walcott, Hone, Sidney, and Charles Bateman. In return, he received a pardon. This also started a long process where accused people confessed, hoping to be forgiven. Using his brother, Keeling got more direct evidence of the plot. Jenkins then brought in Rumsey and West, who told him what they knew starting on June 23. West had already offered information through Laurence Hyde, 1st Earl of Rochester, on June 22. Over several days, West explained the Rye House plot and his role in buying weapons, which he claimed were for America. He didn't say much to accuse the Monmouth group. His statements were later used against Walcott and Sidney. West received a pardon in December 1684.

Thomas Walcott was arrested on July 8 and was the first plotter to go to trial. A meeting of the plotters had been held at his house on June 18. But instead of escaping, he chose to write to Jenkins, offering a full confession in exchange for a pardon. Among the plotters, John Row from Bristol was seen as very untrustworthy. He had a direct connection to Monmouth's household, which he could share as information. Several steps were taken to silence him, and his life was threatened more than once. After the meeting, Nelthorpe and Edward Norton visited William Russell, Lord Russell, asking him to take up arms immediately. When Russell refused, Nelthorpe left the country.

Walcott named Henry Care, who published the Weekly Pacquet, a leading anti-Catholic and Whig newspaper at the time. Care stopped publishing the Pacquet on July 13 and began working with the court. Among those who later gave information against Walcott was Zachary Bourne. Bourne was a plotter who was arrested trying to leave the country with two nonconformist ministers, Matthew Meade (for whom an arrest warrant was issued on June 27) and Walter Cross. He informed against another minister, Stephen Lobb, who was ready to help recruit for an uprising. On July 6, an order was given to arrest Lobb, and he was picked up in August.

A royal statement about how terrible the plot was issued on July 27. Many more people were arrested. Even though the main plotters were less important figures and not directly involved with the "Monmouth cabal," the court treated all groups the same. The ministers involved might have known Ferguson but not West. Meade had hidden John Nisbet, a Covenanter, and might have known about the plans for a rebellion. William Carstares, a Church of Scotland minister and a go-between for the important Whigs, was found in Kent on July 23.

Trials and Punishments

Many people were put on trial for their part in the Rye House Plot. Some were executed, some were pardoned, and others were imprisoned or had to flee the country.

Executed

- Sir Thomas Armstrong, a Member of Parliament – executed.

- John Ayloffe – executed for later involvement in Argyll's Rising.

- Henry Cornish, a Sheriff of the City of London – executed.

- Elizabeth Gaunt – executed.

- James Holloway – executed.

- Baillie of Jerviswood – executed.

- Richard Nelthorpe – executed.

- John Rouse – executed.

- Richard Rumbold – executed for later involvement in Argyll's Rising.

- William Russell, Lord Russell, a Member of Parliament – executed. He became known as a hero for the Whigs.

- Algernon Sidney, a former Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports – executed.

- Thomas Walcott – executed.

Pardoned

These people were sentenced to death but later received a pardon:

Imprisoned

- Sir Samuel Barnardiston, 1st Baronet – also had to pay a large fine.

- Henry Booth, 1st Earl of Warrington

- Paul Foley, a Member of Parliament.

- Thomas Grey, 2nd Earl of Stamford

- John Hampden, a Member of Parliament – also had to pay a very large fine.

- William Howard, 3rd Baron Howard of Escrick – he was arrested and then gave information at the trial of William Russell, Lord Russell in July 1683. His statements about meetings at John Hampden's and Russell's houses helped convict Russell. His evidence also led to Sidney's conviction.

- Matthew Mead

- Aaron Smith

- Sir John Trenchard, a Member of Parliament.

- Sir John Wildman

Exiled or Fled

These people had to leave the country or escaped:

- Sir John Cochrane – fled to the Dutch Republic.

- Robert Ferguson – fled to the Dutch Republic.

- Ford Grey, 3rd Baron Grey of Werke – escaped from the Tower of London to France.

- Patrick Hume, 1st Earl of Marchmont – fled to the Dutch Republic.

- John Locke – fled to the Dutch Republic.

- John Lovelace, 3rd Baron Lovelace – fled to the Dutch Republic.

- David Melville, 3rd Earl of Leven – fled to the Dutch Republic.

- George Melville, 1st Earl of Melville – fled to the Dutch Republic.

- Edward Norton – fled to the Dutch Republic.

- Nathaniel Wade – fled to the Dutch Republic.

Implicated

These people were accused or connected to the plot:

- Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll – executed after Argyll's Rising, though for an earlier charge.

- James Dalrymple, 1st Viscount of Stair

- Edward Hungerford, a Member of Parliament.

- James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, King Charles's son – had to go to the Dutch Republic. He was later executed for leading the Monmouth Rebellion.

- John Owen

- James Burton – he was present when the attack was discussed by his partners. He avoided punishment by accusing Elizabeth Gaunt, a kind Baptist woman, and John Fernley, a poor barber, whose only crimes were helping him escape.

- John Rumsey – arrested because he was suspected of being involved. He saved himself by accusing alderman Henry Cornish.

The last trial related to the Rye House charges was that of Charles Bateman in 1685. Witnesses against him included the plotters Keeling (who didn't have specific details), Thomas Lee, and Richard Goodenough. Bateman was executed.

Sir William Waller had fled abroad the year before. In 1683, he moved to Bremen and became a key figure among the former plotters who were living in exile. Lord Preston, the English ambassador in Paris, called him "the governor" and wrote that "They style Waller, by way of commendation, a second Cromwell". Waller would return to England with William of Orange in 1688, but William chose not to include him in his new government.

What Did Historians Think?

Some historians have suggested that the story of the plot might have been mostly made up by King Charles or his supporters. This would have allowed them to get rid of many of his strongest political opponents. Richard Greaves points to the armed rebellions of the exiled Earl of Argyll and Charles's Protestant son, James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, in 1685 as proof that there was a plot in 1683. Doreen Milne believes that the plot's importance isn't so much about what was actually planned, but more about how the public saw it and how the government used it.

The strong actions taken by the Tories (the King's supporters) in response to the plot, sometimes called the "Stuart Revenge," made many people unhappy. This unhappiness eventually led to the Glorious Revolution of 1688, which changed England's government.

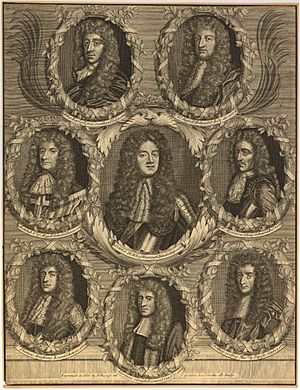

Images for kids

-

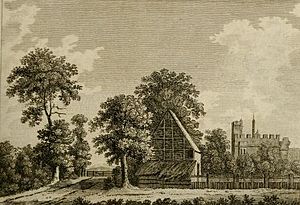

Rye House, Hertfordshire in a 1793 watercolor by J. M. W. Turner

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |