Monmouth Rebellion facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Monmouth Rebellion |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Morning of Sedgemoor, Edgar Bundy |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3,000 | 4,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 200 killed and wounded | 1,300 killed and wounded 2,700 captured |

||||||

| 320 rebels executed 750 rebels transported |

|||||||

The Monmouth Rebellion was a short but important fight in England. It happened in the summer of 1685. This rebellion tried to remove James II from the throne. He had just become king in February 1685.

Many people, especially Protestants, did not want James II as king. This was because he was Catholic. They supported James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, who was the oldest son of the previous king, Charles II. Monmouth was Protestant.

The rebellion started when Monmouth landed in Lyme Regis in June 1685. He hoped to gather a large army and march to London. His army grew, but it was mostly made up of farmers and workers. They were not trained soldiers. The rebellion ended quickly. Monmouth's army was defeated at the Battle of Sedgemoor in July 1685.

Contents

Who Was the Duke of Monmouth?

James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth was the son of King Charles II. However, his mother, Lucy Walter, was not married to the king. This meant Monmouth was an illegitimate son. There were rumors that Charles II had secretly married Lucy Walter. But no proof was ever found. King Charles II always said he only had one wife, Catherine of Braganza.

Monmouth was a skilled military leader. His father, Charles II, made him Commander-in-Chief of the English Army in 1672. He also became Captain General in 1678. He had some success fighting in the Netherlands. He led a British group in the French army during the Third Anglo-Dutch War.

Why Did the Rebellion Happen?

The English Civil War (which ended many years before) left some people unhappy with the monarchy. They remembered the punishments given to those who supported the Commonwealth. In the South West of England, many towns still had strong feelings against the king.

People were also worried about a Catholic king. King Charles II and his wife had no children. This meant his brother, James, who was Catholic, would become king. A man named Titus Oates even claimed there was a "Popish Plot." He said Catholics planned to kill Charles II and put James on the throne.

A powerful politician, the Earl of Shaftesbury, tried to stop James from becoming king. He wanted to "exclude" James from the line of succession. Some members of Parliament even suggested that Monmouth, being Protestant, should be king instead.

King Charles II did not agree with this. He closed down Parliament several times to stop them from passing a law to exclude James.

After a plot to kill both Charles and James in 1683, Monmouth went to the Netherlands. He gathered supporters there. Monmouth was a Protestant. He had visited the South West of England in 1680. People in towns like Chard and Taunton welcomed him warmly.

While Charles II was alive, Monmouth lived a quiet life in Holland. He still hoped to become king peacefully one day. But when James II became king and was crowned in April 1685, Monmouth knew he had to act.

Planning the Uprising

Monmouth planned his rebellion in Holland. It was meant to happen at the same time as another uprising in Scotland. That Scottish rebellion was led by Archibald Campbell, the Earl of Argyll.

Both Argyll and Monmouth started their journeys from Holland. James II's nephew, William III of Orange, was in charge there. He did not stop them from gathering supporters. Argyll sailed to Scotland. There, he gathered fighters mostly from his own family group, the Campbells.

Another important person in Monmouth's rebellion was Robert Ferguson. He was a Scottish religious leader. People called him "the plotter." Ferguson wrote Monmouth's public statement. He also strongly believed Monmouth should be crowned king.

To pay for ships and weapons, Monmouth sold many of his own things. His wife, Anne Scott, 1st Duchess of Buccleuch, and her mother also sold their jewelry. They used the money to rent a Dutch warship called the Helderenberg. A rich widow from London, Ann Smith, gave him £1,000.

Journey to Sedgemoor

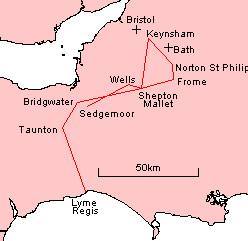

On May 30, 1685, Monmouth sailed to South West England. This area was known for having many Protestants. He had three small ships, four light cannons, and 1,500 guns. On June 11, he landed at Lyme Regis in Dorset with 82 supporters. These included Lord Grey of Warke and Nathaniel Wade. On the first day, about 300 men joined him. They read a long statement written by Ferguson that spoke against the king.

King James had known about the plot for ten days. He quickly learned of Monmouth's arrival. The mayor of Lyme Regis told the local soldiers. Two customs officers rode quickly to London to tell the king.

To fight Monmouth, John Churchill was put in charge of the king's regular soldiers. The main leader of the king's army was the Huguenot Earl of Feversham. It would take days for the king's army to get to the west country. So, local groups of soldiers had to defend first.

Over the next few days, more people joined Monmouth. By June 15, he had over 1,000 men. On June 13, Monmouth lost two important supporters. Two men argued over a horse. One shot and killed the other. The shooter was arrested and sent back to the ship.

The next day, some of Monmouth's men went to Bridport. They met 1,200 local soldiers loyal to the king. The king's soldiers won this small fight. Many of the local soldiers then left their side and joined Monmouth's army.

Monmouth heard that more of the king's soldiers were coming. He left Lyme Regis. Instead of marching to London, he headed north into Somerset. On June 15, he fought with local soldiers at Axminster and took the town. More people joined his army. It grew to about 6,000 men. Most were farmers and workers. They were armed with farm tools like pitchforks. A famous writer, Daniel Defoe, was one of his young supporters.

Monmouth again spoke against the king in Chard. On June 20, he was crowned king in Taunton. Some of his supporters did not want this. The town leaders of Taunton were forced to watch. In Taunton, Monmouth gained many new supporters. He formed a new group of 800 men.

Churchill's soldiers kept getting closer to Monmouth. They arrived in Chard on June 19. They tried to stop new people from joining Monmouth in Taunton. Feversham moved his soldiers into Bristol. He thought Bristol would be Monmouth's next target. Feversham then took charge of the whole campaign.

Monmouth and his growing army continued north to Bridgwater. He stayed at Bridgwater Castle on June 21. Then he went to Glastonbury (June 22) and Shepton Mallet (June 23). The weather got worse. Meanwhile, the king's navy captured Monmouth's ships. This meant he could not escape back to Europe. The king's armies also got more soldiers from London.

On June 24, Monmouth's army camped at Pensford. A small group fought with the local soldiers from Gloucester. They wanted to control Keynsham, an important place to cross the River Avon. Monmouth made Keynsham Abbey his base there.

Monmouth wanted to attack Bristol. It was the largest city in England after London. But he heard that the city was already held by the king's soldiers. There were small fights with the king's soldiers led by Feversham. These fights made it seem like there were more royalist soldiers than there really were. Some historians think if Monmouth had marched quickly to Bristol, he might have taken the city. If Bristol had been taken, more people might have joined the rebellion. Then, a march on London might have been possible.

On June 26, Monmouth moved towards Bath. He found that it was also held by the king's soldiers. He camped for the night in Philips Norton (now Norton St Philip). On June 27, Feversham's soldiers attacked Monmouth's forces there. Monmouth's half-brother led some soldiers into the village. They were surrounded by the rebels. They had to fight their way out. They were saved by Churchill. Both sides had about twenty people hurt. But each side thought the other had lost more.

Monmouth then marched all night to Frome, arriving on June 28. The spirits of Monmouth's soldiers began to fall. News arrived that the rebellion in Scotland had failed. Argyll's small army had fought some small battles. But after arguments with his supporters, his army became smaller. The Scottish rebellion failed.

The rebels planned to go to Warminster next. Many Protestant wool workers lived there. But on June 27, the local soldiers from Wiltshire marched from Bath to Trowbridge. On June 29, they entered Westbury. Monmouth heard that an army supporting him was near Bridgwater. So, he turned back through Shepton Mallet. He arrived in Wells on July 1. His men damaged the Bishop's Palace and the front of Wells Cathedral. They took lead from the roof to make bullets. They broke windows and smashed the organ. For a time, they even kept their horses in the church.

Feversham wanted to keep the rebels in the South West. He was waiting for more of his soldiers to arrive. These included soldiers sent by William III of Orange from Holland. People were spreading rumors that the rebels had 40,000 soldiers. They also said 500 of the king's soldiers were lost at Norton St Philip. So, Feversham was ordered to fight Monmouth's army. On June 30, the last parts of Feversham's army arrived. This included his cannons. Monmouth was pushed back to the Somerset Levels. On July 3, he was trapped in Bridgwater. He told his soldiers to make the town stronger.

The Battle of Sedgemoor

Monmouth was finally defeated by Feversham and Churchill on July 6. This happened at the Battle of Sedgemoor.

Once Monmouth's army was in Bridgwater, he sent some of his horsemen to get six cannons from Minehead. He planned to stay in Bridgwater until they returned. Then he would break out and go to Bristol. Feversham and his army of 500 horsemen and 1,500 local soldiers camped near Sedgemoor. They were at the village of Westonzoyland. Monmouth could see them from the church tower in Bridgwater. He may have looked at them more closely from the church in Chedzoy. Then he decided to attack them.

The Duke led his untrained and poorly armed soldiers out of Bridgwater around 10:00 pm. They planned a night attack on the king's army. A local farmer's helper guided them. They went along the old Bristol road towards Bawdrip. Their small group of horsemen led the way. They turned south along Bradney Lane and Marsh Lane. They came to the open moor. This area had deep and dangerous drainage ditches called rhynes.

There was a delay while they crossed a ditch. The first men to cross surprised a group of the king's soldiers. A shot was fired. A horseman from the king's group rode off quickly to tell Feversham. Lord Grey led the rebel horsemen forward. They were met by the king's horsemen. This alerted all the king's soldiers.

The king's army was better trained. Their horses were also better. They quickly defeated the rebels by going around their sides. Monmouth's untrained supporters were easily beaten. Hundreds were killed by cannons and guns.

Historians say between 727 and 2,700 rebels died. The king's army lost 27 men. These men were buried in the churchyard of the Church of St Mary the Virgin in Westonzoyland. This church was used as a prison for the rebel soldiers.

After the Battle

Monmouth ran away from the battle. But he was caught in a ditch on July 8. This happened either in Ringwood or Horton. Before the rebellion, Parliament had already passed a special law. This law said Monmouth was a traitor and should be put to death. So, no trial was needed before his execution.

Monmouth begged for mercy. He even claimed he had become Catholic. But he was beheaded at Tower Hill on July 15, 1685. It is said that it took many hits with the axe to cut off his head. Some sources say it took eight hits. The Tower of London website says five. Another book claims it was seven. The character Jack Ketch in "Punch and Judy" is named after the executioner, Jack Ketch. Monmouth's titles were taken away. But some of his family's titles were later given back to the Duke of Buccleuch.

After the rebellion, there were many trials for Monmouth's supporters. These were called the Bloody Assizes. They were led by Judge Jeffreys. In these trials, 320 people were sentenced to death. About 800 others were sent to work hard for ten years in the West Indies.

King James II used the end of the rebellion to make his power stronger. He asked Parliament to remove some laws. He also appointed Catholics to important jobs. He made the standing army bigger. Parliament did not agree with many of these changes. So, on November 20, 1685, James sent Parliament home.

In 1688, James II had a son. This meant there would be a Catholic king after him. Many Protestant leaders were very unhappy. So, James II was removed from power by William of Orange. This event is known as the Glorious Revolution.