Wells Cathedral facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Wells Cathedral |

|

|---|---|

| Cathedral Church of St Andrew | |

The beautiful West Front of Wells Cathedral.

|

|

| 51°12′37″N 2°38′37″W / 51.2104°N 2.6437°W | |

| Location | Wells, Somerset |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholic |

| History | |

| Dedication | Saint Andrew |

| Consecrated | 23 October 1239 |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Grade I listed building |

| Designated | 12 November 1953 |

| Style | Gothic (Early English, Decorated, and Perpendicular) |

| Years built | 1176 – c. 1490 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 126.5 m (415 ft) |

| Width | 20 m (66 ft) |

| Width across transepts | 47 m (154 ft) |

| Nave height | 20.5 m (67 ft) |

| Number of towers | 3 |

| Tower height |

|

| Bells | 10 |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Bath and Wells (since c. 909) |

| Province | Canterbury |

Wells Cathedral is a famous Church of England cathedral in Wells, Somerset, England. It is dedicated to St Andrew. The cathedral is the main church for the Diocese of Bath and Wells and the official seat of the bishop. It holds daily services and welcomes over 300,000 visitors each year. Because of its historical importance, it is a Grade I listed building.

The cathedral is known for its stunning Gothic architecture. It was one of the first buildings in England to be built entirely in this new style, breaking away from the older, heavier Romanesque style. Its west front, or main entrance, is covered in over 300 beautiful statues.

The area around the cathedral, called the precincts, includes the historic Bishop's Palace and Vicars' Close, a medieval street where the choir singers have lived for centuries.

Contents

History of the Cathedral

The First Churches on the Site

The story of Wells Cathedral begins a long time ago. The oldest discovery on the site is a tomb from the time of the Romans. Later, in the year 705, a church was built by King Ine of Wessex. This church was dedicated to St Andrew. Parts of this very old church, like the font used for baptisms, can still be seen inside the cathedral today.

In 909, Wells became the center of a new church district, or diocese. The first bishop was named Athelm. During this time, a choir of boys was started to sing at services. This was the beginning of the Wells Cathedral School, which still educates the cathedral's choristers.

Building the Gothic Cathedral

The cathedral we see today was started around 1175 by Bishop Reginald Fitz Jocelin. It was designed in the new Gothic style, with pointed arches and tall, elegant shapes. This was a very modern style at the time. The main parts of the church were finished by 1239.

Over the next few centuries, more parts were added. A beautiful eight-sided room called the chapter house was built. The central tower was made taller, and a special chapel, the Lady chapel, was added to the east end.

A bishop named Ralph of Shrewsbury built Vicars' Close to give the choir singers a safe place to live. He also built a wall and a moat around his palace to protect it.

In the 14th century, people noticed that the central tower was so heavy it was causing the pillars below it to sink. To fix this, a clever builder named William Joy inserted unique arches that look like giant scissors. These "strainer arches" have become one of the most famous features of the cathedral.

Later History and Restoration

The cathedral was mostly complete by the time of King Henry VII. However, it faced difficult times. During the English Civil War in the 1640s, soldiers damaged the building, breaking windows and furniture. The cathedral fell into disrepair for a while.

After the war, repairs began. In 1661, a new dean named Robert Creighton donated the large west window. But in 1685, during the Monmouth Rebellion, more damage was done by soldiers who stabled their horses inside the nave.

By the 19th century, the cathedral needed a major restoration. Old paint was removed, and the choir area was rearranged. In recent years, another large restoration project began on the west front to clean and protect its amazing statues. This work started in April 2025.

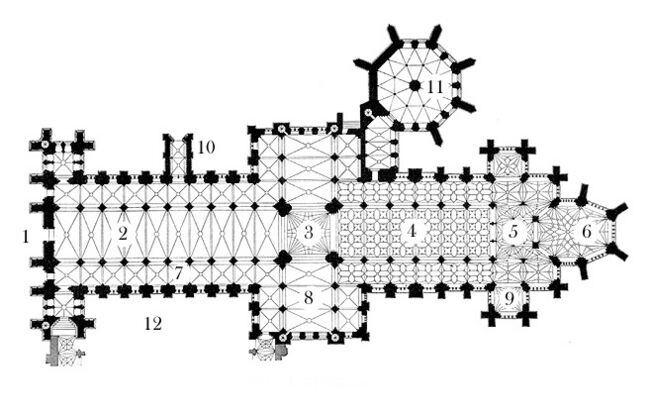

Architecture: A Gothic Masterpiece

- West front

- Nave (the main body of the church)

- Central tower

- Choir (where the choir sings)

- Retrochoir (the area behind the choir)

- Lady Chapel

- Aisle (the walkways on either side)

- Transept (the parts that form the cross shape)

- East transept

- North porch

- Chapter house

- Cloister (a covered walkway)

Wells is famous for being one of England's first truly Gothic cathedrals. The builders used pointed arches, clustered columns, and large windows to create a feeling of height and light.

The inside of the cathedral is divided into three levels: a main arcade of arches, a gallery called the triforium, and an upper level of windows called the clerestory. The nave, or main hall, is known for its strong horizontal lines, which make it feel very long and graceful.

The Famous West Front

The west front is the main entrance of the cathedral and is like a giant outdoor art gallery. It is 100 feet (30 m) high and 147 feet (45 m) wide. It was originally decorated with around 400 statues, and about 300 of them still survive.

The statues are arranged in rows and show many different figures. There are kings, queens, bishops, and angels. There are also scenes from the Bible, such as stories from the Old and New Testaments. At the very top, in the gable, there was once a statue of Christ as Judge, with the twelve apostles below. Many of these statues were once painted in bright colors.

Scissor Arches and Chapter House

Inside, the most eye-catching features are the "scissor arches" at the center of the cathedral. These were added around 1338 to support the weight of the central tower. They form a bold 'X' shape and are a brilliant piece of medieval engineering.

The chapter house is another architectural treasure. It is an octagonal (eight-sided) room where the cathedral's leaders used to meet. In the center, a single column fans out into 32 ribs that support the roof, looking like a giant stone palm tree. The room is lined with 51 seats, each with a canopy decorated with funny and interesting carved heads.

Art and Treasures Inside

Stained Glass Windows

Wells Cathedral has a wonderful collection of medieval stained glass. Some of the oldest glass dates back to the 13th century.

The most famous window is the "Golden Window" at the east end of the choir. It dates from around 1340 and shows the Tree of Jesse, which is the family tree of Jesus. It gets its name from the beautiful golden colors created by a special technique called silver staining.

Stone Carvings and Misericords

The cathedral is filled with amazing stone carvings. The tops of the pillars, called capitals, are decorated with lively carvings of leaves in a style known as "stiff-leaf." Some capitals even tell stories, like one showing a farmer chasing boys who were stealing his fruit.

The choir stalls have special hinged seats called misericords. When the seat is tipped up, it reveals a small ledge that clergy could lean on during long services. Underneath these ledges are fantastic carvings. They show all sorts of scenes, including animals, mythical creatures like dragons, and funny pictures of everyday life.

The Astronomical Clock

In the north transept is the Wells Cathedral clock, one of the oldest working clocks in the world. It was made around 1390. The clock face shows the time on a 24-hour dial, as well as the positions of the sun and moon.

Every 15 minutes, a small figure called Jack Blandifers strikes the bells. When the hour strikes, a set of jousting knights rushes out and circles around above the clock. There is another clock face on the outside wall that is run by the same mechanism.

Music at the Cathedral

Music has been a huge part of life at Wells Cathedral for over 1,100 years. The world-famous Wells Cathedral Choir is made up of boys and girls who are educated at the Wells Cathedral School. They sing at daily services along with the Vicars Choral, a group of professional adult singers.

The cathedral is also home to a magnificent organ, built by Harrison & Harrison in 1910. It has a powerful sound that fills the huge space. The cathedral also hosts concerts and has its own oratorio society, a large choir that performs major musical works.

Images for kids

-

The baptismal font from the Saxon church of Aldhelm (c. 705) is over 400 years older than the cathedral itself.

-

A 1999 sculpture, The Weight of our Sins, by Josefina de Vasconcellos in the grounds of the Bishop's Palace.

-

From the reflecting pool in the grounds of the Bishop's Palace.

-

A chantry in the nave (photo Francis Bedford, 19th century).

-

A pair of parakeets in a pine tree.

See also

In Spanish: Catedral de Wells para niños

In Spanish: Catedral de Wells para niños

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |