George III of Great Britain and Ireland facts for kids

George III (born George William Frederick; 4 June 1738 – 29 January 1820) was a British king who ruled for a very long time. He was King of Great Britain and Ireland from 1760 until 1801. Then, these two kingdoms joined together, and he became King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. He was also a ruler in Germany, first as an Elector and later as King of Hanover.

George III was part of the House of Hanover royal family. Unlike the kings before him, he was born in Great Britain and spoke English as his first language. He never even visited Hanover, the German region his family came from.

His time as king was filled with many wars. Great Britain fought against France in the Seven Years' War and became a very strong power in North America and India. However, Britain later lost many of its American colonies in the American War of Independence. George III also led Britain through wars against Napoleon until 1815. In 1807, the transatlantic slave trade was made illegal in the British Empire.

Later in his life, King George III suffered from a serious mental illness. The exact cause is still unknown, but some think it might have been bipolar disorder or a blood disease called porphyria. In 1810, he became very ill, and his oldest son, the Prince of Wales, took over as Prince Regent the next year. When George III died in 1820, his son became King George IV. George III was the longest-living and longest-reigning British king.

Contents

- Early Life and Education

- Becoming King and Getting Married

- Early Years as King

- The American War of Independence

- Working with William Pitt the Younger

- Signs of Illness

- Abolishing the Slave Trade

- Wars with France

- Final Years and Death

- Legacy of George III

- Titles and Royal Symbols

- George III's Children

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life and Education

George was born in London on 4 June 1738. He was the grandson of King George II. His parents were Frederick, Prince of Wales, and Augusta of Saxe-Gotha. He was born two months early, so people thought he might not survive.

George grew up to be a healthy, quiet, and a bit shy. He and his younger brother, Edward, were taught at home by private tutors. By the age of eight, he could read and write in both English and German. He was the first British king to study science in a planned way.

His lessons included science subjects like chemistry, physics, and astronomy. He also studied maths, French, Latin, history, music, geography, and law. He learned sports and social skills like dancing, fencing, and riding. His religious education was strictly Anglican. When he was 10, George acted in a play and said, "What, tho' a boy! It may with truth be said, A boy in England born, in England bred." This showed his pride in being British.

In 1751, his father, Prince Frederick, died suddenly. This meant George became the next in line to the throne. Three weeks later, King George II made him Prince of Wales.

When George was almost 18, the King offered him his own royal home. But George refused, following advice from his mother and her friend, Lord Bute. Lord Bute later became prime minister. George's mother wanted him to stay home so she could teach him strong moral values.

Becoming King and Getting Married

In 1759, George was interested in Lady Sarah Lennox. But Lord Bute told him not to marry her. George decided to put his duty first, writing, "I am born for the happiness or misery of a great nation." He knew he had to act against his own feelings sometimes.

The next year, on 25 October 1760, George became king at age 22. His grandfather, George II, had died suddenly. The search for a suitable wife became very important. After looking at many German princesses, George's mother chose Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. Charlotte accepted the marriage offer.

Charlotte arrived in London on 8 September 1761. They were married that same evening at Chapel Royal, St James's Palace. Two weeks later, on 22 September, they were both crowned at Westminster Abbey. George III was known for being faithful to his wife, unlike other kings. They had a happy marriage until his illness began.

The King and Queen had 15 children: nine sons and six daughters. In 1762, George bought Buckingham House, which is now Buckingham Palace. He used it as a family home. He also had homes at Kew Palace and Windsor Castle. He did not travel much and spent his whole life in southern England. In the 1790s, he made Weymouth, Dorset, a popular seaside resort by taking his family there for holidays.

Early Years as King

George III wanted to show he was truly British. In his first speech to Parliament, he said, "Born and educated in this country, I glory in the name of Britain." He wanted to be different from his German ancestors, who seemed to care more about Hanover than Britain. During his long reign, Britain was a constitutional monarchy. This meant the government was run by ministers and Parliament, not just the king.

At first, politicians welcomed George. But his early years as king were unstable. This was mainly because of disagreements about the Seven Years' War. George was seen as favoring Tory ministers, which made the Whigs call him a ruler who wanted too much power.

The King's personal lands did not make much money. Most of the government's money came from taxes. George gave control of his royal lands to Parliament. In return, Parliament gave him money each year to support his household and government costs. Historians say claims that he used this money to bribe supporters are false. Parliament paid off over £3 million in royal debts during his reign. George also gave a lot of his own money to charity and helped the Royal Academy of Arts. He was a great collector of books, and his "King's Library" became the start of a new national library.

In 1762, the Whig government was replaced by one led by Lord Bute, a Scottish Tory. A Member of Parliament named John Wilkes wrote articles criticizing Bute. Wilkes was arrested but escaped to France. He was removed from Parliament. In 1763, Lord Bute resigned after ending the Seven Years' War with the Peace of Paris. Britain gained a lot of land, including Canada.

Later that year, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 limited where American colonists could settle. This upset some colonists. The British government felt the American colonies should help pay for their own defense. The main issue for the colonists was not the amount of taxes, but that Parliament was taxing them without their approval. They believed in "no taxation without representation" because they had no representatives in Parliament.

In 1765, Prime Minister George Grenville introduced the Stamp Act. This law put a tax on every document in the American colonies. People who printed newspapers were most affected, and they created a lot of opposition to the tax. George III was unhappy with Grenville and replaced him with Lord Rockingham.

Lord Rockingham, with the King's support, removed the unpopular Stamp Act. But his government was weak, and William Pitt the Elder became prime minister in 1766. Pitt was very popular in America for helping repeal the Stamp Act. Statues of him and George III were even put up in New York City. Pitt became ill, and Augustus FitzRoy, 3rd Duke of Grafton, took over the government.

In 1770, the Tories, led by Lord North, came to power. George III was a very religious man. He was upset by his brothers' loose morals. In 1771, his brother Cumberland married a woman the King thought was not suitable. George insisted on a new law, the Royal Marriages Act 1772. This law said that members of the royal family could not marry without the King's permission.

Lord North's government focused on problems in America. Most taxes were removed, except for the tea tax. George III wanted to keep this one tax to show Britain's right to tax the colonies. In 1773, colonists threw tea into Boston Harbor in an event known as the Boston Tea Party. British opinion turned against the colonists.

Parliament supported Lord North's actions, which the colonists called the Intolerable Acts. These acts closed the Port of Boston and changed the government of Massachusetts. Historians say George III wanted a peaceful solution and supported his ministers. He acted as a constitutional monarch, meaning he followed the advice of his government.

The American War of Independence

The American War of Independence was a major conflict. In the 1760s, American colonists resisted new taxes from Parliament. They had no direct say in Parliament and felt their rights as Englishmen were being ignored. Fighting began in April 1775 at Battles of Lexington and Concord. The colonists sent requests to the King to help with Parliament, but these were ignored. The King then declared the rebel leaders traitors.

In July 1776, the colonies declared their independence. They listed many complaints against the King and Parliament. They said George III had "plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people." A statue of the King in New York was pulled down.

Even though Prime Minister Lord North was not the best war leader, George III kept Parliament focused on the fight. Lord North's ministers, however, were not strong leaders, which helped the American war effort.

Some people accuse George III of stubbornly continuing the war in America. But historians say that at the time, no king would easily give up such a large territory. His actions were also less harsh than other European monarchs. After the Battle of Saratoga, both Parliament and the British people supported the war.

In 1778, Louis XVI of France, Britain's main rival, signed a treaty with the United States. The conflict became a "world war," affecting North America, Europe, and India. Spain also joined France in 1779. The Dutch Republic was divided, with some helping the Americans and others helping Britain.

In 1779, a combined French-Spanish fleet threatened to invade England. George III called it the "most serious crisis the nation ever knew." But the invasion failed due to sickness and bad weather. George III wanted to send more troops to the West Indies, saying, "We must risk something, otherwise we will only vegetate in this war."

Opposition to the costly war grew. In 1780, there were riots in London called the Gordon riots. Despite some British victories, news of Lord Cornwallis's surrender at siege of Yorktown in late 1781 led to Lord North's resignation. The King even wrote an abdication notice, but never delivered it. He finally accepted defeat in North America. The Treaties of Paris in 1783 recognized American independence and returned Florida to Spain. George III admitted, "America is lost!"

When John Adams became the first American minister to London in 1785, George III had accepted the new relationship. He told Adams that he was the last to agree to the separation, but now that it was done, he would be the first to seek friendship with the United States.

Working with William Pitt the Younger

After Lord North's government fell in 1782, there were several changes in prime ministers. The King strongly disliked Charles James Fox, a powerful politician. In 1783, a government led by the Duke of Portland, with Fox and Lord North, came to power.

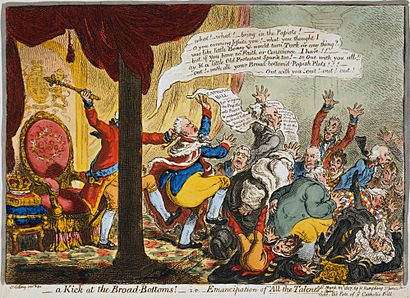

The King was very unhappy about having ministers he didn't like. He was even more upset when the government tried to change how India was governed, giving power to Fox's allies. George III secretly told the House of Lords that he would see anyone who voted for this bill as his enemy. The bill was rejected. Three days later, the King dismissed the government and appointed William Pitt the Younger as prime minister. Pitt was very young, only 24. Parliament was dissolved, and the next election gave Pitt a strong mandate.

Pitt's appointment was a big win for George III. It showed that the King could choose prime ministers based on public opinion, even if they weren't the choice of the current majority in Parliament. George supported Pitt's goals and even created new noble titles to increase Pitt's supporters in the House of Lords. During Pitt's time as prime minister, George III became very popular in Britain. People admired him for his strong faith and for being loyal to his wife. He loved his children but set strict rules for them. He was disappointed when his sons didn't follow his moral principles.

Signs of Illness

By this time, George's health was getting worse. He suffered from a mental illness that caused periods of extreme excitement and confusion. Some experts think it was bipolar disorder, while others suggest a genetic blood disease called porphyria. A study of his hair in 2005 found high levels of arsenic, which could have caused his illness.

He had a short illness in 1765, and a more serious one began in 1788. He became very confused, sometimes speaking for hours without stopping. His doctors didn't understand his illness. Treatments at the time were very basic, like physically restraining him.

In Parliament, politicians argued about who should rule while the King was ill. Both agreed that the Prince of Wales should be regent (a temporary ruler). But they disagreed on how much power the Prince should have. Before Parliament could pass a law, George III recovered.

Abolishing the Slave Trade

During George III's reign, many people in Britain began to oppose slavery. There were also slave uprisings in the Americas. George III himself never bought or sold slaves. He also never invested in companies involved in the slave trade. He even wrote a document in the 1750s against slavery. However, he and his son, the Duke of Clarence, supported delaying the end of the British slave trade for almost 20 years. Prime Minister Pitt wanted to abolish slavery, but the King's views meant it wasn't official government policy.

During the American War of Independence, a British governor, Lord Dunmore, offered freedom to slaves of American rebels if they joined the British army. Later, George III's commanding general, Henry Clinton, expanded this promise. About 20,000 freed slaves fought for George III. In 1783, about 3,000 former slaves settled in Nova Scotia with British certificates of freedom.

Between 1791 and 1800, British ships transported almost 400,000 Africans to the Americas as slaves. But on 25 March 1807, George III signed the Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. This law banned the transatlantic slave trade in the British Empire.

Wars with France

After George's recovery, his popularity grew. The French Revolution of 1789, which overthrew the French monarchy, worried many British landowners. France declared war on Great Britain in 1793. George allowed Pitt to raise taxes, build armies, and suspend certain rights to deal with the crisis.

Britain formed coalitions with other European countries to fight France, but these failed. Only Great Britain was left fighting Napoleon Bonaparte, the leader of France. A short break in the fighting allowed Pitt to focus on Ireland, where there had been an uprising. In 1801, Great Britain and Ireland united to form the "United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland." George III also stopped using the old title "King of France."

Pitt planned to remove some laws that limited the rights of Roman Catholics. But George III believed this would break his coronation oath to protect Protestantism. Pitt threatened to resign, and the King had another relapse of his illness. He blamed it on worrying about the Catholic issue. Pitt was replaced by Henry Addington in 1801. Addington made peace with France in 1802.

George III did not believe the peace with France would last. The war started again in 1803. Napoleon planned to invade England, and many volunteers joined the British army to defend the country. George III reviewed thousands of volunteers in London. He wrote that he was ready to lead his troops if Napoleon landed. After Admiral Lord Nelson's victory at the Battle of Trafalgar, the threat of invasion ended.

In 1804, George's illness returned. After he recovered, Addington resigned, and Pitt became prime minister again. Pitt wanted to include Fox in his government, but George refused. Pitt focused on forming new alliances against France. These alliances also failed. Pitt's health suffered, and he died in 1806.

Lord Grenville became Prime Minister. His government included Fox and passed the Slave Trade Act 1807, which banned the slave trade. After Fox died, the King and government disagreed again. The government proposed allowing Catholics to serve in all ranks of the armed forces. George III refused and demanded they never propose such a measure again. The ministers were dismissed and replaced. George III made no more major political decisions after this.

Final Years and Death

In late 1810, King George, who was almost blind and suffered from pain, had another serious mental breakdown. He believed it was caused by the death of his youngest and favorite daughter, Princess Amelia. George accepted that a Regency Act 1811 was needed. His son, the Prince of Wales, became regent for the rest of the King's life. By the end of 1811, George III was permanently ill and lived quietly at Windsor Castle until he died.

Prime Minister Spencer Perceval was assassinated in 1812. Lord Liverpool took over and led Britain to victory in the Napoleonic Wars. The Congress of Vienna later made Hanover a kingdom.

George's health continued to worsen. He developed dementia and became completely blind and mostly deaf. He didn't know that he was declared King of Hanover in 1814, or that his wife died in 1818. In his last weeks, he could not walk. He died of pneumonia at Windsor Castle on 29 January 1820, at 81 years old. His funeral was held on 16 February at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle.

Legacy of George III

George III was followed by two of his sons, George IV and William IV. Neither had surviving children, so the throne eventually went to Queen Victoria, the daughter of George III's fourth son.

George III lived for over 81 years and reigned for almost 60 years. Both his life and reign were longer than any previous British king. Only Queens Victoria and Elizabeth II lived and reigned longer.

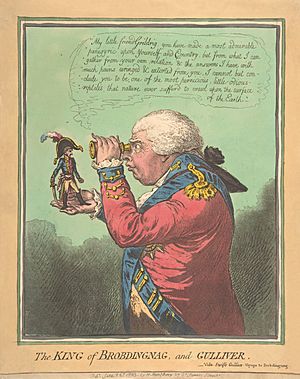

George III was sometimes called "Farmer George" by people who made fun of his interest in farming instead of politics. But later, this nickname showed him as a man of the people. During his reign, the British Agricultural Revolution greatly improved farming. There were also big advances in science and industry. The population grew, providing workers for the Industrial Revolution.

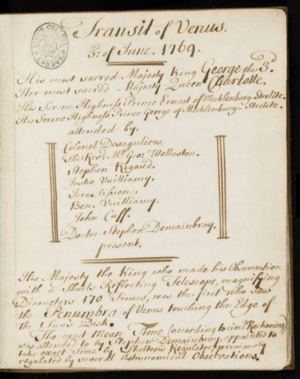

George III had a collection of scientific instruments, which are now at the Science Museum, London. He had the King's Observatory built for his own observations of the 1769 transit of Venus. When William Herschel discovered the planet Uranus in 1781, he first named it Georgium Sidus (George's Star) after the King. George III also helped fund Herschel's large telescope.

George III has been seen in different ways throughout history. At first, he was very popular. But by the mid-1770s, he lost the loyalty of the American colonists. The United States Declaration of Independence presented him as a tyrant. Some early British historians also had negative views of him.

However, in the mid-20th century, historians like Lewis Namier began to re-evaluate George III. They saw him more sympathetically, as a victim of his time and his illness. Modern scholars believe that George III was defending Parliament's right to tax the colonies, not trying to gain more power for himself. During his long reign, the monarchy continued to lose political power but became a symbol of national values.

Titles and Royal Symbols

Titles and Styles of George III

- 4 June 1738 – 31 March 1751: His Royal Highness Prince George

- 31 March 1751 – 20 April 1751: His Royal Highness The Duke of Edinburgh

- 20 April 1751 – 25 October 1760: His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales

- 25 October 1760 – 29 January 1820: His Majesty The King

Before 1801, George III's official title in Great Britain was "George the Third, by the Grace of God, King of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, and so forth." In 1801, when Great Britain and Ireland united, he dropped the title "King of France." This title had been used by English kings since Edward III in the Middle Ages. His new title became "George the Third, by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland King, Defender of the Faith."

In Germany, he was also the "Duke of Brunswick and Lüneburg" and an "Elector of the Holy Roman Empire" until 1806. In 1814, he became "King of Hanover."

Honours and Awards

Great Britain: Royal Knight of the Garter, 22 June 1749

Great Britain: Royal Knight of the Garter, 22 June 1749 Ireland: Founder of the Most Illustrious Order of St. Patrick, 5 February 1783

Ireland: Founder of the Most Illustrious Order of St. Patrick, 5 February 1783

Royal Coat of Arms

Before he became king, George had a special version of the royal arms. After his father died, he inherited another version as the Prince of Wales.

From 1760 to 1800, his royal arms showed symbols for England, Scotland, France, and Ireland. It also included symbols for Hanover in Germany. After the Acts of Union 1800 in 1801, the French symbol was removed. In 1816, when Hanover became a kingdom, the symbol for Hanover on the arms was changed to show a crown.

George III's Children

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| George IV | 12 August 1762 | 26 June 1830 | Became Prince of Wales in 1762; married Caroline of Brunswick in 1795; had one daughter, Princess Charlotte. |

| Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany | 16 August 1763 | 5 January 1827 | Married Princess Frederica of Prussia in 1791; no children. |

| William IV | 21 August 1765 | 20 June 1837 | Duke of Clarence and St Andrews; married Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen in 1818; no surviving legitimate children. |

| Charlotte, Princess Royal | 29 September 1766 | 6 October 1828 | Married King Frederick of Württemberg in 1797; no surviving children. |

| Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn | 2 November 1767 | 23 January 1820 | Married Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld in 1818; their daughter was Queen Victoria. |

| Princess Augusta Sophia | 8 November 1768 | 22 September 1840 | Never married, no children. |

| Princess Elizabeth | 22 May 1770 | 10 January 1840 | Married Frederick, Landgrave of Hesse-Homburg in 1818; no children. |

| Ernest Augustus, King of Hanover | 5 June 1771 | 18 November 1851 | Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale; married Frederica of Mecklenburg-Strelitz in 1815; had children. |

| Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex | 27 January 1773 | 21 April 1843 | Married Lady Augusta Murray in 1793 (marriage later cancelled); married Lady Cecilia Buggin in 1831; no children from second marriage. |

| Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge | 24 February 1774 | 8 July 1850 | Married Princess Augusta of Hesse-Kassel in 1818; had children. |

| Princess Mary | 25 April 1776 | 30 April 1857 | Married Prince William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh in 1816; no children. |

| Princess Sophia | 3 November 1777 | 27 May 1848 | Never married, no children. |

| Prince Octavius | 23 February 1779 | 3 May 1783 | Died as a child. |

| Prince Alfred | 22 September 1780 | 20 August 1782 | Died as a child. |

| Princess Amelia | 7 August 1783 | 2 November 1810 | Never married, no children. |

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Jorge III del Reino Unido para niños

In Spanish: Jorge III del Reino Unido para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |