Jacobite rising of 1715 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Jacobite Rising of 1715 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Jacobite risings | |||||||

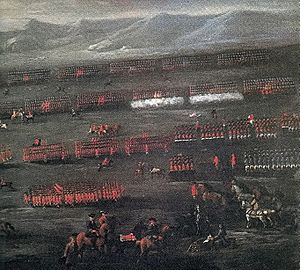

The Battle of Sheriffmuir, John Wootton |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Duke of Argyll Charles Wills George Carpenter |

Earl of Mar Earl of Strathmore Thomas Forster |

||||||

The Jacobite Rising of 1715 was a big attempt by James Edward Stuart to get back the thrones of England, Ireland, and Scotland. He was known as the Old Pretender. His family, the Stuarts, had been forced out of power.

The rebellion started in Braemar, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. A local leader, the Earl of Mar, gathered his supporters on August 27. He wanted to capture Stirling Castle. However, he was stopped by a smaller army led by the Duke of Argyll. This happened at Sheriffmuir on November 13. The battle had no clear winner. But the Earl of Mar thought he had won and left the battlefield. The rebellion ended after the Jacobites surrendered at Preston on November 14.

Contents

Why the Rising Happened

The story of the Jacobite Rising starts in 1688. This was when King James II and VII was removed from the throne. This event is called the Glorious Revolution. His Protestant daughter, Mary II, and her Dutch husband, William III, became the new rulers.

A law called the Act of Settlement 1701 was passed in 1701. It said that no Catholic could ever be king or queen of Britain. This meant James's son, James Francis Edward Stuart, could not become king. Queen Anne, James's Protestant half-sister, had no children who lived. So, the law named a distant relative, Sophia of Hanover, as the next in line. She died shortly before Queen Anne in 1714.

This made Sophia's oldest son, George I of Great Britain, the next king. He became King George I in August 1714. This change gave the Whig party a lot of power in the government.

France had supported the Stuart family in exile. But France agreed to the new Protestant kings of Britain. This was part of the peace deal that ended a big war called the War of the Spanish Succession. This helped King George I take the throne smoothly. Later, the Stuarts were even told to leave France.

Some politicians in Britain were also unhappy. The previous government had been hard on the Whigs. Now the Whigs were in power and accused their rivals, the Tories, of bad things. Some Tory leaders were arrested or had to flee the country. One of them, Lord Bolingbroke, went to France. He became James's new helper.

James hoped for support from many people. He even wrote to the Pope for help. He believed that many in England would join him. He thought it was his best chance to become king.

The Rebellion Begins

The Earl of Mar did not wait for James to tell him to start the rebellion. He sailed from London to Scotland. On August 27, he held a meeting in Braemar, Aberdeenshire. On September 6, he officially started the uprising at Braemar. He raised a flag for "James the 8th and 3rd." About 600 people cheered him on.

The British Parliament reacted quickly. They passed a law that allowed them to arrest people without trial. They also passed a law to take land from Jacobite leaders who rebelled. This land would then be given to their tenants who stayed loyal to the government. Some of Mar's own tenants went to Edinburgh. They wanted to show they were loyal and get his land.

Fighting in Scotland

In northern Scotland, the Jacobites had some early success. They took over towns like Inverness, Gordon Castle, and Aberdeen. Further south, they captured Dundee. But they could not take Fort William.

In Edinburgh Castle, the government kept many weapons and a lot of money. This money was paid to Scotland when it joined with England. A Jacobite leader named Lord Drummond tried to take the Castle at night. He had 80 men and a ladder. But the ladder was too short! They were stuck until morning and then arrested.

By October, the Earl of Mar's army had grown very large, almost 20,000 men. They controlled almost all of Scotland north of the Firth of Forth. Only Stirling Castle remained in government hands. But Mar was not very decisive. His army captured Perth and moved south. This was likely due to his officers, not Mar himself. Mar's slowness gave the government commander, the Duke of Argyll, time to get more soldiers. He received help from the army in Ireland.

On October 22, James officially made Mar the commander of the Jacobite army. Mar's forces were three times bigger than Argyll's army. Mar decided to march towards Stirling Castle. On November 13, the two armies met at Sheriffmuir. The battle was not a clear win for either side. Near the end, the Jacobites still had 4,000 men, while Argyll had only 1,000. Mar's army started to move towards Argyll, who was not well protected. But Mar did not attack closely. He might have thought he had already won the battle. Argyll had lost more men than Mar. Instead of finishing the fight, Mar went back to Perth.

On the same day as the Battle of Sheriffmuir, Inverness was taken by government forces. Also, a smaller Jacobite group led by Mackintosh of Borlum was defeated at Preston.

The Fight in England

In western England, some Jacobite leaders were planning a rebellion. These included important noblemen and members of Parliament. But the government found out and arrested them on October 2. Parliament quickly agreed to these arrests. The government sent more soldiers to protect cities like Bristol, Southampton, and Plymouth.

The city of Oxford was known for supporting the king. The government suspected them. On October 17, General Pepper led soldiers into Oxford. He arrested some Jacobite leaders there without any trouble.

Even though the main rebellion in the West was stopped, another one started in Northumberland on October 6, 1715. This group included two noblemen, James Radclyffe, 3rd Earl of Derwentwater, and William Widdrington, 4th Baron Widdrington. Other important people joined them later in Lancashire.

The English Jacobites joined forces with Scottish Jacobites from the borderlands. This small army also met up with Mackintosh's group. They marched into England. Government forces caught up with them at the Battle of Preston from November 12-14. The Jacobites did well on the first day, causing many government losses. But more government soldiers arrived the next day. The Jacobites eventually had to surrender.

On November 15, 3,000 Dutch soldiers arrived in England. They landed near the Thames river. Later, another 3,000 landed in Hull. The Dutch sent these troops to help Britain. This was part of a deal they had made to protect the Protestant line of kings. These Dutch soldiers helped in some smaller fights in Scotland.

What Happened Next

James finally landed in Scotland at Peterhead on December 22. But by the time he reached Perth on January 9, 1716, his army was much smaller, less than 5,000 men. Meanwhile, Argyll's government forces had powerful cannons and were moving fast. Mar decided to burn villages between Perth and Stirling. This was to stop Argyll's army from getting supplies.

On January 30, Mar led the Jacobites out of Perth. On February 4, James wrote a goodbye letter to Scotland. He sailed away from Montrose the next day.

Many Jacobite prisoners were put on trial. Some were executed. However, a law passed in July 1717, called the Indemnity Act, pardoned most of those who had taken part in the Rising. But one group, the entire Clan Gregor, including Rob Roy MacGregor, was specifically not pardoned.

In the years that followed, James, the Old Pretender, tried two more times to become king. In 1719, he was defeated again, even with help from Spain. James's son, Charles Edward Stuart, known as the Young Pretender, tried to win the throne for his father in 1745. But he was defeated at the Battle of Culloden. James died in 1766.

See also