Exclusion Crisis facts for kids

The Exclusion Crisis was a big political argument in England from 1679 to 1681. It happened during the time of King Charles II. The main goal was to stop the King's brother, James, Duke of York, from becoming the next king. Why? Because James was Catholic.

People in Parliament tried three times to pass a law, called an "Exclusion Bill," to block James. But none of these laws ever passed. This crisis led to the creation of England's first two main political groups. The Tories were against stopping James from becoming king. The "Country Party," who soon became known as the Whigs, wanted to exclude him.

Even though James wasn't stopped during Charles's reign, the issue came up again. Just three years after James became king, he was removed from power in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Later, a law called the Act of Settlement 1701 finally made it clear: no Catholic could ever be the ruler of England, Scotland, or Ireland (which later became Great Britain).

Contents

Why Was James a Problem?

In 1673, it became public that James, the Duke of York, was a Roman Catholic. This happened when he refused to take an oath required by a new law called the Test Act. This law said that people in important public jobs had to swear they were not Catholic.

Over the next few years, many people worried about the King and his court. They seemed to be getting too friendly with France, which had a powerful Catholic king, Louis XIV. People feared England might become like France, with a king who had total power and was Catholic.

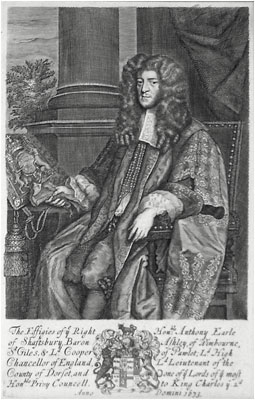

One important politician, the First Earl of Shaftesbury, often spoke out. He warned that a government with too much power and Catholicism could harm Parliament, the country, and English rights. These fears grew stronger because James was openly Catholic. Also, there was a secret agreement called the Secret Treaty of Dover (1670). This treaty showed Charles II was secretly getting money from France.

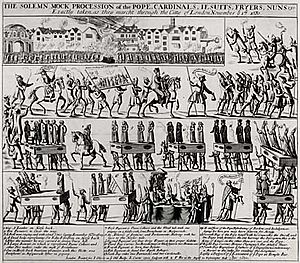

In 1678, a man named Titus Oates claimed there was a "Popish Plot" to kill King Charles II and put James on the throne. James's secretary, Edward Colman, was named as a plotter. Many English people, who were mostly Anglican Protestant, saw how King Louis XIV ruled France with absolute power. They did not want this type of rule in England. King Charles II had no legal children, so James was next in line. Many feared James would rule like Louis XIV.

Sir Henry Capel, a Member of Parliament, summed up the feelings in 1679:

From popery (Catholicism) came the idea of a standing army and total power... If we get rid of Catholicism, then total government power will end. It's just an idea without Catholicism.

The Crisis Begins

A big scandal helped start the Exclusion Crisis. Thomas Osborne, Earl of Danby, who was a top government official, was accused of wrongdoing. He had helped King Charles II get secret money from King Louis XIV of France. This made anti-Catholic feelings in Parliament even stronger. Members of Parliament then pushed to stop James from becoming king.

Danby had tried to get the King to turn away from France. But his efforts to get money for the King backfired. In 1677, Danby convinced Charles to raise an army. The idea was to scare the French into paying England to avoid a war. However, when France won a battle against the Dutch in 1678, Parliament wanted an immediate war with France.

Knowing the King didn't have enough money, Danby had to accept a secret French offer. France would give Charles money for an alliance. Letters about this secret deal were found by other Members of Parliament. When Parliament learned about it in 1678, they voted to accuse Danby of serious crimes. They said he had taken too much power, tried to bring in absolute rule by raising an army, and was "popishly affected" (meaning he liked Catholics).

Danby tried to keep his job. King Charles even dissolved Parliament to save him from a trial. But the next Parliament, called the Habeas Corpus Parliament, was even more against the King and Danby. They sent Danby to the Tower of London in March 1679.

On May 15, 1679, supporters of Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, introduced the Exclusion Bill. This bill aimed to stop James from becoming king. Some people even started supporting the idea of Charles's son, the Duke of Monmouth, becoming king instead. Monmouth was Protestant, but he was not born in wedlock.

It looked like the bill would pass in the House of Commons. So, King Charles used his royal power to dissolve Parliament again. New Parliaments were elected, and they also tried to pass the Exclusion Bill. Each time, Charles dissolved them.

New Political Parties Emerge

The Exclusion Crisis is often seen as the time when England's first real political parties appeared.

- Whigs: Those who supported the Exclusion Bill and wanted Parliament to meet were called 'Petitioners'. They later became known as the Whigs. They were worried about a Catholic king and royal power.

- Tories: Those who were against the Exclusion Bill were called 'Abhorrers'. They developed into the Tories. They supported the King's right to choose his successor.

It's interesting that Shaftesbury, who was against James, actually got money from King Louis XIV of France. Louis XIV wanted to cause trouble in England to weaken it. The Whigs used the Popish Plot to get more support. But some moderate people became worried by the extreme fear it caused. For example, 22 people were executed because of the plot, and even the Queen was accused of trying to poison her husband.

Many of Shaftesbury's supporters, like the Earl of Huntingdon, changed sides. After two failed attempts to pass the Exclusion Bill, Charles II successfully made the Whigs look like troublemakers. King Louis XIV then switched his support to Charles. This allowed Charles to dissolve the 1681 Oxford Parliament. Charles did not call Parliament again during his reign. This took away the Whigs' main way to get political power. A failed plot in 1683, called the Rye House Plot, further weakened the Whigs.

A Lasting Change: Habeas Corpus

One important result of the crisis was the strengthening of the Habeas Corpus law. This was the only real achievement of the short-lived Habeas Corpus Parliament of 1679. The Whig leaders passed this law because they feared the King might try to arrest them unfairly.

The Habeas Corpus Act made sure that a person arrested had the right to be brought before a judge quickly. The judge would then decide if the arrest was legal. This law lasted much longer than the crisis itself. It had a huge impact on the British legal system and later on the American one too. It protects people from being held in prison without a good reason.

The Crisis in Stories

Robert Neill's 1972 book The Golden Days tells a story about the Exclusion Crisis. It follows two Members of Parliament from a small town. Sir Harry Burnaby is a strong supporter of the King. Richard Gibson is a former soldier and a member of the new Whig party. Even though they have very different political ideas, they respect each other. They both worry that the crisis could lead to another civil war in England. In the end, Burnaby's son marries Gibson's daughter, with both fathers' approval.

See also

- Religion in the United Kingdom

- British monarchy

- Popery

- Popish Plot

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |