History of Kenya facts for kids

A part of Eastern Africa, the country of Kenya has been home to humans for a very long time, since the early Stone Age. Around 1,000 years ago, people speaking Bantu languages moved into the area from West Africa. Today, Kenya is a country with many different ethnic groups because it's where Bantu, Nilo-Saharan, and Afro-Asiatic language groups meet. The Wanga Kingdom was set up in the late 1600s, uniting the Wanga people and Luhya tribe under one king, called the Nabongo.

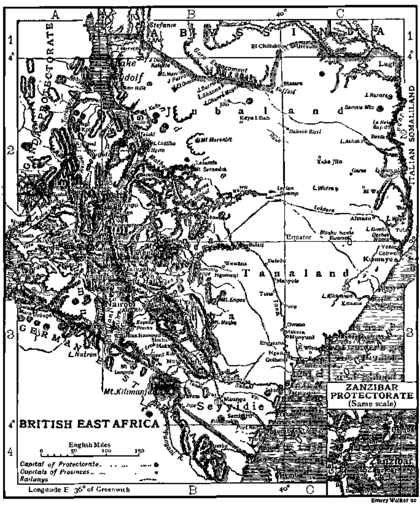

Europeans and Arabs arrived in Mombasa a long time ago, but Europeans started exploring the inner parts of Kenya in the 1800s. The British Empire took control and created the East Africa Protectorate in 1895, which later became the Kenya Colony in 1920.

In the 1960s, many African countries became independent. Kenya gained its freedom from the United Kingdom in 1963. Elizabeth II was its first head of state, and Jomo Kenyatta became its first Prime Minister. Kenya became a republic in 1964.

Contents

- Ancient Times: Early Humans in Kenya

- New Stone Age: Farmers and Herders Arrive

- Iron Age: New Tools and Cultures

- Swahili Culture and Trade: A Coastal Story

- Portuguese and Omani Influences: New Powers Arrive

- 1800s: Growing Influence and Change

- British Rule (1895–1963): The Colonial Era

- Independence: A New Nation

- See also

Ancient Times: Early Humans in Kenya

Fossils found in Kenya show that primates lived here over 20 million years ago! In 1929, the first signs of early human ancestors in Kenya were found by Louis Leakey. He discovered one million-year-old Acheulian handaxes at the Kariandusi Prehistoric Site.

Many types of early humans have been found in Kenya. The oldest, found in 2000 by Martin Pickford, is Orrorin tugenensis, which is six million years old. It was named after the Tugen Hills where it was found.

In 1995, Meave Leakey named a new human species, Australopithecus anamensis, after finding fossils near Lake Turkana. These fossils are about 4.1 million years old.

In 2011, very old stone tools, 3.2 million years old, were found at Lomekwi near Lake Turkana. These are the oldest stone tools ever found anywhere!

One of the most complete early human skeletons ever found is the 1.6-million-year-old Homo erectus known as Nariokotome Boy. It was discovered in 1984 by Kamoya Kimeu.

Scientists believe that East Africa, including Kenya, is one of the first places where modern humans (Homo sapiens) lived. In 2018, evidence from Olorgesailie in Kenya showed that modern behaviors, like trading goods over long distances and using colors, started around 320,000 years ago.

In 2021, even more evidence of modern behavior was found: Africa's oldest funeral! A 78,000-year-old grave of a three-year-old child was discovered in Panga ya Saidi cave. Researchers believe the child's head was placed on a pillow, and the body was laid in a curled-up position. This shows how early humans cared for each other.

New Stone Age: Farmers and Herders Arrive

The first people in what is now Kenya were hunter-gatherer groups. The Kansyore culture, from about 4500 BCE to 1000 BCE, was one of the first groups in East Africa to make pottery. This culture was found at Gogo Falls near Lake Victoria.

Kenya also has ancient rock art sites, dating from 2000 BCE to 1000 CE, found on Mfangano Island and other places. These paintings were likely made by the Twa people, who were hunter-gatherers. Over time, many of these communities joined with groups who started farming and raising animals.

Around 3000 BCE, people who spoke Southern Cushitic languages moved into northern Kenya. They were pastoralists, meaning they raised animals like cattle, sheep, goats, and donkeys. They built amazing stone sites, including Namoratunga, which might have been used to study the stars. One of these sites, Lothagam North Pillar Site, is East Africa's oldest and largest cemetery. By 1000 BCE, animal herding had spread into central Kenya.

Later, around 700 BCE, people speaking Southern Nilotic languages moved south into western Kenya and the Rift Valley. This happened just before iron was introduced to East Africa.

Iron Age: New Tools and Cultures

Iron production started in West Africa as early as 3000–2500 BCE. The ancestors of Bantu speakers moved from west/central Africa and spread across much of Eastern, Central, and Southern Africa starting around 1000 BCE. They brought with them the skill of working with iron and new farming methods. The Bantu expansion reached western Kenya around 1000 BCE.

The Urewe culture was one of Africa's oldest places for smelting iron. From 550 BCE to 650 BCE, this culture was important in the Great Lakes region, including Kenya. By the first century BCE, Bantu-speaking communities in this region learned how to make carbon steel.

Later, more migrations through Tanzania led to settlements on the Kenyan coast. By 100 BCE to 300 CE, Bantu-speaking communities were living in coastal areas of Kenya, Tanzania, and Somalia. They mixed and married with the people already living there. Between 300 CE and 1000 CE, these communities traded with Arab and Indian merchants through the Indian Ocean trade route, which helped create the unique Swahili culture.

Historians believe that in the 1400s, Southern Luo speakers began moving into Western Kenya from South Sudan and Uganda. As they moved, they mixed with other communities already living in the region.

The walled settlement of Thimlich Ohinga is a large and well-preserved stone structure built around Lake Victoria. It is at least 550 years old and shows that different ethnic groups lived there over time.

Swahili Culture and Trade: A Coastal Story

Swahili people live along the Swahili coast in East Africa, which includes parts of Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Mozambique. This coast has many islands, cities, and towns like Mombasa, Malindi, and Lamu. In ancient times, this area was known as Azania or Zanj.

An old Greek-Roman book from the first century CE, called the Periplus of the Erythrean Sea, describes the East African coast and its long-standing Indian Ocean trade routes. Evidence of pottery and farming from as far back as 3000 BCE has been found along the coast. Trade goods from far away, like Greek-Roman pottery and Syrian glass, have also been discovered, showing early international connections.

Bantu groups moved to the Great Lakes Region by 1000 BCE, and some continued to the East African Coast. They mixed with the local people. The earliest settlements on the Swahili coast were in Kenya, Tanzania, and Somalia. These communities were skilled in ironwork, farming, hunting, and fishing, and they traded with outside areas.

Between 300 CE and 1000 CE, settlements on the Swahili coast grew, and local industries and international trade thrived. From 500 to 800 CE, they focused more on sea trade and began to move south by ship. In the following centuries, trade in goods like gold, ivory, and slaves helped market towns like Mogadishu and Mombasa grow. These towns became the first city-states in the region.

By the first century CE, many settlements like Mombasa and Malindi started trading with Arabs. This led to economic growth, the introduction of Islam, and Arabic influences on the Swahili language and culture. Islam spread quickly across Africa. Many historians used to think Arab or Persian traders created these city-states, but now we know they grew from local communities, though they were influenced by foreign trade.

The Swahili communities had a lot of cultural exchange. For example, between 630 CE and 890 CE, crucible steel was made in Galu, south of Mombasa. This shows a mix of African and Asian metalworking techniques. The Swahili City States became more defined between 1000 CE and 1500 CE. The oldest Swahili writings, based on Arabic letters, also come from this time.

A famous Moroccan explorer, Ibn Battuta, visited Mombasa in 1331. He described it as a large island with many fruit trees. He noted that the local people were Sunni Muslims, who were religious and trustworthy. He also mentioned their well-built wooden mosques. Another famous traveler, Chinese Admiral Zheng He, visited Malindi in 1418. Some of his ships reportedly sank near Lamu Island. Recent genetic tests show that some local residents have Chinese ancestors!

Swahili, a Bantu language with many Arabic words, became a common language for trade between different peoples. A unique Swahili culture developed in towns like Pate, Malindi, and Mombasa.

Portuguese and Omani Influences: New Powers Arrive

Portuguese explorers arrived on the East African coast in the late 1400s. They wanted to set up naval bases to control trade in the Indian Ocean. After many small fights, Arabs from Oman defeated the Portuguese in Kenya.

Vasco da Gama was the first European to explore the region of present-day Kenya, visiting Mombasa in April 1498. His voyage opened direct sea trade routes between Portugal and Asia, challenging older trade networks.

Portuguese rule in East Africa mainly focused on a coastal strip around Mombasa. Their presence officially began in 1505. They aimed to control trade and demand high taxes on goods. They built Fort Jesus in Mombasa in 1593 to strengthen their power.

The Omani Arabs were the biggest challenge to the Portuguese. Omani forces captured Fort Jesus in 1698. By 1730, the Omanis had driven the remaining Portuguese from the coasts of Kenya and Tanzania. The Portuguese then lost interest in the spice trade route because it was no longer as profitable.

Under Seyyid Said (who ruled from 1807–1856), the Omani sultan moved his capital to Zanzibar in 1840. The Arabs then set up long-distance trade routes into the African interior. These routes connected the Kenyan coast to kingdoms in Uganda. Arab, Shirazi, and coastal African cultures mixed, forming an Islamic Swahili people who traded in many goods, including slaves.

1800s: Growing Influence and Change

Omani Arab rule brought the once independent city-states on the Kenyan and Tanzanian coasts under foreign control, even more than the Portuguese had. The Omanis mainly controlled the coastal areas, not the interior. However, they started large farms and increased the slave trade. When Sultan Seyyid Said moved his capital to Zanzibar in 1839, the demand for slaves grew even more. Slaves were brought from deep inside Kenya, from areas near Mount Kenya and Lake Victoria.

Arab control of the major ports continued until British interests, especially their desire to protect their trade with India and stop the slave trade, put pressure on Omani rule. By the late 1800s, the British had largely stopped the slave trade on the open seas. The Omani Arabs did not resist the Royal Navy's efforts to end slavery. The official Omani Arab presence in Kenya ended in the 1880s when Germany and Britain took control of key ports and made alliances with local leaders. However, many Omani Arab descendants still live along the coast today.

The first Christian mission in Kenya was started on August 25, 1846, by Dr. Johann Ludwig Krapf, a German missionary. He set up a station among the Mijikenda people at Rabai on the coast. He later translated the Bible into Swahili. Many freed slaves rescued by the British Navy were settled here. The slave plantation economy was at its peak in East Africa between 1875 and 1884. It's thought that between 43,000 and 47,000 slaves were on the Kenyan coast, making up 44% of the local population. In 1874, the Frere Town settlement in Mombasa was created for more freed slaves. Even with British pressure, the East African slave trade continued into the early 1900s.

By 1850, European explorers began mapping the interior of Kenya. European interest grew because of the island of Zanzibar, which became a base for trade and exploration. By 1840, countries like Britain, France, Germany, and America had opened offices in Zanzibar to protect their business interests. Also, Europeans wanted more African products like ivory and cloves. Finally, Britain wanted to end the slave trade, and later, German competition further increased British interest in East Africa.

British Rule (1895–1963): The Colonial Era

East Africa Protectorate: British Control Begins

In 1895, the British government took control of the interior of Kenya, calling it the East Africa Protectorate. In 1902, the border was extended to Uganda, and in 1920, most of this large protectorate became a crown colony. When colonial rule began in 1895, the fertile Rift Valley and surrounding Highlands were set aside for white settlers. In the 1920s, Indian communities protested this, especially since many British war veterans were given land. White settlers started large coffee farms, relying mostly on Kikuyu workers. This caused tension between Indians and Europeans.

This fertile land had always attracted people and led to conflicts. There were no major mineral resources like gold or diamonds that attracted people to South Africa.

Imperial Germany had set up a protectorate over the Sultan of Zanzibar's coastal lands in 1885. Then, Sir William Mackinnon's British East Africa Company (BEAC) arrived in 1888. Germany later gave its coastal holdings to Britain in 1890 in exchange for control over the coast of Tanganyika.

Because the British East Africa Company had money problems, the British government took direct control on July 1, 1895, creating the East African Protectorate. They then opened the fertile highlands to white settlers in 1902.

A key development for Kenya's interior was the railway, started in 1895, from Mombasa to Kisumu on Lake Victoria, finished in 1901. This was the first part of the Uganda Railway. The British government built this railway mainly for strategic reasons, to connect Mombasa with the British protectorate of Uganda. This "Uganda railway" was a huge engineering achievement and helped modernize the area.

About 32,000 workers were brought from British India to build the railway. Many stayed, along with Indian traders and small business owners, who saw opportunities in the newly opened interior. To make the railway profitable, rapid economic development was needed. Since Africans were used to farming for their own needs rather than for export, the government encouraged European settlement in the fertile highlands, where few Africans lived. The railway opened up the interior to European farmers, missionaries, and administrators, and also to government programs against slavery, witchcraft, disease, and famine. The British colonial administration passed laws against witchcraft, giving people a legal way to deal with suspected witches.

By the time the railway was built, African military resistance to British takeover had mostly ended. However, new problems arose from European settlement. For example, the Maasai people were forced to move from the fertile Laikipia plateau to a drier area in 1913 to make way for Europeans. The Kikuyu also felt they had lost their land.

In the early colonial period, the British worked with traditional chiefs. Later, as they wanted more efficiency, newly educated young men joined old chiefs in local councils.

The British faced strong local opposition while building the railway, especially from Koitalel Arap Samoei, a Nandi leader. He predicted a "black snake" would tear through Nandi land, spitting fire, which was seen as the railway line. He fought against the railway for ten years. In 1907, settlers were allowed some say in government through the legislative council. They wanted more power and achieved this in 1920 when Kenya became a Crown Colony. Africans were not allowed direct political participation until 1944.

First World War: Kenya's Role

Kenya became an important British military base during the First World War (1914–1918). At the start of the war, British and German governors in East Africa agreed to a truce to keep their colonies out of fighting. However, Lt Col Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck took command of German forces and fought a successful guerrilla war, tying down many British resources. He surrendered in Zambia eleven days after the war ended in 1918. To chase von Lettow, the British brought in troops from India and needed many African porters to carry supplies. The Carrier Corps mobilized over 400,000 Africans, which helped them become more politically aware in the long run.

Kenya Colony: Growing Resistance

An early anti-colonial movement called Mumboism started in South Nyanza in the early 1900s. It was seen as a religious cult by colonial authorities but is now recognized as a movement against colonial rule. It spread among the Luo people and Kisii people. The colonial government suppressed it by deporting and imprisoning its followers.

The first modern African political groups in Kenya Colony protested against policies favoring settlers, increased taxes on Africans, and the hated kipande (an identification tag worn around the neck). After World War I, new taxes, lower wages, and new settlers threatening African land led to new movements. Harry Thuku formed the Young Kikuyu Association (YKA) and published Tangazo, criticizing the colonial administration. The YKA gave many Kikuyu a sense of nationalism and encouraged peaceful resistance. Thuku later renamed his organization the East African Association to include other ethnic groups and the Indian community. The colonial government arrested him for rebellion, and he was held until 1930.

In Kavirondo (later Nyanza province), a strike at a mission school raised concerns about African land ownership. Meetings were held, advocating for individual land titles, ending the kipande system, and fairer taxes. Archdeacon W. E. Owen, an Anglican missionary, helped organize this movement.

In the mid-1920s, the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA) was formed, mainly representing the Kikuyu. Johnstone Kenyatta was its secretary and editor of its publication, Mugwithania (The Unifier). The KCA worked to unite the Kikuyu and fought for Harry Thuku's release. The government banned the KCA after World War II began.

Most political activity between the wars was local. As Kenya modernized after the war, British religious missions changed their focus. They started emphasizing medical, humanitarian, and educational programs, especially due to the threat of the Mau Mau uprisings.

Kenya African Union: A Push for Rights

Because they were excluded from political representation, the Kikuyu people, who faced the most pressure from settlers, started Kenya's first African political protest movement in 1921, the Young Kikuyu Association, led by Harry Thuku. After it was banned, the Kikuyu Central Association took its place in 1924.

In 1944, Thuku founded the multi-ethnic Kenya African Study Union (KASU), which became the Kenya African Union (KAU) in 1946. This was an African nationalist organization that demanded access to land owned by white settlers. KAU was mainly made up of Kikuyu, but its leaders came from different ethnic groups. In 1947, Jomo Kenyatta, a former leader of the Kikuyu Central Association, became president of the KAU, demanding a stronger political voice for Africans. His efforts inspired Oginga Odinga, a leader of the Luo community, to join KAU and enter politics.

In response to growing pressure, the British Colonial Office allowed more members into the Legislative Council and gave it a bigger role. By 1952, a system of quotas allowed for elected European, Arab, and Asian members, along with African and Arab members chosen by the governor. The council of ministers became the main governing body in 1954.

In 1952, Princess Elizabeth and her husband Prince Philip were on holiday at the Treetops Hotel in Kenya when her father, King George VI, died. Elizabeth immediately returned home to become Queen. As British conservationist Jim Corbett said, she went up a tree in Africa a princess and came down a queen.

Mau Mau Uprising: A Fight for Freedom

A major turning point happened from 1952 to 1956 during the Mau Mau Uprising. This was an armed local movement mainly against the colonial government and European settlers. It was the largest and most successful such movement in British Africa. Many leaders of the rebellion were World War II veterans, including Stanley Mathenge, Bildad Kaggia, and Fred Kubai. Their war experiences made them determined to change the system.

Key leaders of KAU, known as the Kapenguria Six, were arrested on October 21, 1952. They included Jomo Kenyatta, Paul Ngei, Kungu Karumba, Bildad Kaggia, Fred Kubai, and Achieng Oneko. Kenyatta denied leading the Mau Mau but was convicted and imprisoned in 1953, gaining his freedom in 1961.

The Mau Mau uprising led to events that sped up Kenya's independence. A Royal Commission on Land and Population said that reserving land based on race was wrong. To fight the rebellion, the colonial government made changes that removed many protections for white settlers. For example, Africans were allowed to grow coffee, a major cash crop, for the first time. Harry Thuku was one of the first Kikuyu to get a coffee license. Racist policies in public places were also eased. A British official stated that the effort to suppress Mau Mau showed that settlers could not manage alone, and the British government was not willing to shed more blood to keep colonial rule.

Trade Unions and the Road to Independence

The pioneers of the trade union movement were Makhan Singh, Fred Kubai, and Bildad Kaggia. They organized strikes, including a railway workers' strike in 1939. These leaders were imprisoned during the crackdown on Mau Mau. After this, all national African political activity was banned.

Trade unions, led by younger Africans, filled the gap left by the banned political parties. They became the only organizations that could mobilize large groups of people. Tom Mboya was one of these young leaders. He became the Director of Information for KAU at age 22. After KAU was banned, Mboya used the Kenya Federation of Registered Trade Unions (KFRTU) to represent African political issues as its Secretary General at age 26. Mboya later started the Kenya Federation of Labour (KFL), which became the most active political group in Kenya. Mboya's success in trade unionism earned him respect and international connections, especially with labor leaders in the United States of America. He used these connections to challenge the colonial government.

Many trade union leaders who fought for independence through the KFL later became members of parliament and government ministers. The trade union movement became a major battleground in the cold war that affected Kenyan politics in the 1960s.

Constitutional Debates and Independence

After the Mau Mau uprising was put down, the British allowed the election of six African members to the Legislative Council. Tom Mboya successfully ran for office in 1957. Daniel Arap Moi and Oginga Odinga were also elected. Mboya's party, the Nairobi People's Convention Party (NPCP), became very organized and effective in mobilizing people in Nairobi to demand more African representation. The new colonial constitution of 1958 increased African representation, but African nationalists began to demand "one man, one vote." However, Europeans and Asians, being minorities, feared what universal voting would mean for them.

In June 1958, Oginga Odinga called for the release of Jomo Kenyatta. This call gained momentum. A big problem for self-rule was the lack of educated Africans. This inspired Tom Mboya to start a program, funded by Americans, to send talented young people to the United States for higher education. There was no university in Kenya at the time, and colonial officials opposed the program. The next year, Senator John F. Kennedy helped fund the program, which became known as The Kennedy Airlift. This scholarship program trained about 70% of the new nation's top leaders, including Wangari Maathai, the first African woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize, and Barack Obama Sr., the father of former US President Barack Obama.

At a conference in London in 1960, African members and British settlers agreed on a path toward independence. Following this, a new African party, the Kenya African National Union (KANU), was formed with the slogan "Uhuru" (Freedom). It was led by James S. Gichuru and Tom Mboya. KANU was formed in May 1960 when several groups merged. Mboya was a key figure until his death in 1969. A split in KANU led to a rival party, the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU), led by Ronald Ngala and Masinde Muliro. In the 1961 elections, KANU won most of the African seats. Kenyatta was finally released in August and became president of KANU in October.

Independence: A New Nation

In 1962, a KANU-KADU coalition government was formed, including both Kenyatta and Ngala. The 1962 constitution created a two-house legislature and divided the country into seven semi-independent regions. The system of reserved seats for non-Africans was ended, and open elections were held in May 1963. KANU won majorities in the Senate and House of Representatives. Kenya then achieved internal self-government with Jomo Kenyatta as its first president.

The British and KANU agreed to changes in October 1963 that strengthened the central government, making Kenya a single-party state in practice. Kenya gained full independence on December 12, 1963, as the Commonwealth realm of Kenya. It was declared a republic on December 12, 1964, with Jomo Kenyatta as Head of State. In 1964, further changes centralized the government, and important organizations like the Central Bank of Kenya were formed in 1966.

The British government bought out the white settlers, and most of them left Kenya. The Indian minority controlled retail businesses in cities, but Africans deeply mistrusted them. As a result, many Indians left Kenya, mostly for Britain.

Kenya's very fast population growth and many people moving from rural areas to cities led to high unemployment and disorder in the cities. There was also a lot of resentment from Black Kenyans towards the privileged economic position of Asians and Europeans.

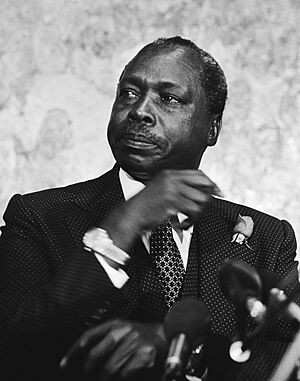

When Kenyatta died on August 22, 1978, Vice-president Daniel arap Moi became interim President. On October 14, Moi officially became president. In June 1982, the constitution was changed, making Kenya officially a one-party state. On August 1, 1982, members of the Kenyan Air Force tried to overthrow the government, but loyal forces quickly stopped it.

Independent Kenya, though officially neutral, leaned towards Western countries. Kenya tried to unite with Tanzania and Uganda to form an East African union, but it didn't happen. However, the three nations did form a loose East African Community (EAC) in 1967, which kept some shared customs and services. The EAC broke apart in 1977. Kenya's relations with Somalia worsened because of Somalis in the North Eastern Province who wanted to break away and were supported by Somalia. In 1968, Kenya and Somalia agreed to restore normal relations, and the Somali rebellion ended.

Recent History (1978–Present): Modern Kenya

Kenyatta died in 1978 and was succeeded by Daniel arap Moi (born 1924, died 2020), who ruled as President from 1978 to 2002.

In 1993, Moi's government agreed to economic reforms suggested by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. This helped Kenya get enough aid to manage its foreign debt.

Moi was not allowed to run in the December 2002 presidential elections because of the constitution. He tried to promote Uhuru Kenyatta, the son of Kenya's first President, as his successor, but it was unsuccessful. A group of opposition parties, called the National Rainbow Coalition (NaRC), defeated the ruling KANU party. Their leader, Mwai Kibaki, who was Moi's former vice-president, was elected president by a large majority.

On December 27, 2002, 62% of voters elected members of the National Rainbow Coalition (NaRC) to parliament and chose NaRC candidate Mwai Kibaki (born 1931) as president. Voters rejected Uhuru Kenyatta, the candidate chosen by outgoing president Moi. Observers said the 2002 elections were fairer and less violent than previous ones. Kibaki's strong win allowed him to choose a cabinet and gain international support.

Kenya's economy recovered well, with annual growth improving from -1.6% in 2002 to 5.5% in 2007. However, social inequalities also increased, and corruption became a big problem. Ordinary Kenyans faced more crime in cities and conflicts between ethnic groups fighting over land.

The 3rd President of Kenya, Mwai Kibaki, ruled from 2002 until 2013.

In 2013, Uhuru Kenyatta (son of the first president Jomo Kenyatta) won a presidential election that had some disputes. In 2017, he won a second term in office.

In March 2018, a historic event called the handshake happened between President Uhuru Kenyatta and his long-time opponent Raila Odinga. This led to reconciliation, economic growth, and more stability in the country.

In August 2022, Deputy President William Ruto narrowly won the presidential election with 50.5% of the vote. His main rival, Raila Odinga, received 48.8%. On September 13, 2022, William Ruto was sworn in as Kenya's fifth president.

|

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Kenia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Kenia para niños

- Timeline of Kenya

- Leaders:

- Colonial Heads of Kenya

- Heads of Government of Kenya (12 December 1963 to 12 December 1964)

- Heads of State of Kenya (12 December 1964 to today)

- Politics of Kenya

- History of cities in Kenya:

- History of Africa

- History of Uganda

- History of Tanzania

- List of human evolution fossils

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |