Manning Clark facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Manning Clark

|

|

|---|---|

Clark in his study, circa 1988

|

|

| Born |

Charles Manning Hope Clark

3 March 1915 Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

|

| Died | 23 May 1991 (aged 76) Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia

|

| Nationality | Australian |

| Alma mater | University of Melbourne University of Oxford |

| Spouse(s) | Dymphna Clark |

| Children | Andrew, Axel, Benedict, Katerina, Rowland, Sebastian |

| Awards | Moomba Book Award (1969) Henry Lawson Arts Award (1969) Australian Literature Society Gold Medal (1970) The Age Non-Fiction Award (1974) Companion of the Order of Australia (1975) Douglas Stewart Prize for Non-Fiction (1979) Australian of the Year (1980) |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | Australian National University (1960–74) University of Melbourne (1944–60) |

| Notable students | Frank Crean Geoffrey Serle Ken Inglis Geoffrey Blainey Helen Hughes Humphrey McQueen |

| Influences | Thomas Carlyle Edward Gibbon Thomas Macaulay |

| Influenced | Geoffrey Serle Lyndall Ryan |

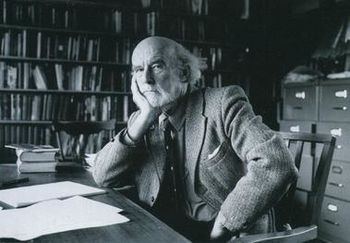

Charles Manning Hope Clark (born March 3, 1915 – died May 23, 1991) was a very famous Australian historian. He wrote a well-known six-book series called A History of Australia. These books were published between 1962 and 1987. Many people consider him "Australia's most famous historian." However, his work also received a lot of criticism, especially from conservative thinkers.

Contents

Growing Up in Australia

Clark was born in Sydney on March 3, 1915. His father, Charles Clark, was an English priest from a working-class family. His mother, Catherine Hope, came from an old, well-known Australian family. Manning Clark had a difficult relationship with his mother. He felt she looked down on his father's background.

When Clark was a child, his family moved to Melbourne. They lived with a modest income, which meant they were not rich. Clark's happiest childhood memories were from 1922 to 1924. During these years, his father was a vicar on Phillip Island. Here, Clark developed a love for fishing and cricket, which he enjoyed his whole life.

He went to state schools in Cowes and Belgrave. Later, he attended Melbourne Grammar School. As a quiet boy from a less wealthy background, he faced teasing and bullying. This experience made him dislike the wealthy students who went to that school.

However, his later school years were better. He discovered a passion for literature and classic studies. He became an excellent student in Greek, Latin, and history. In 1933, he was one of the top students at his school.

Clark won a scholarship to Trinity College at the University of Melbourne. He did very well there, earning top grades in ancient and British history. He also became the captain of the college cricket team. By this time, he had lost his Christian faith. His political views changed over time, from liberalism to a moderate form of socialism.

Studying at Oxford

In 1937, Clark won another scholarship to Balliol College at Oxford University in England. He left Australia in August 1938. At Oxford, he impressed people by being good at cricket. He played for the Oxford team.

While studying, he visited Nazi Germany in 1938. He saw the horrors of fascism firsthand. This experience made him feel more pessimistic about Europe's future. In 1939, he married Dymphna Lodewyckx in Oxford. She was a talented scholar, and they had six children together.

Teaching and Research Career

When World War II started in 1939, Clark was excused from military service because he had mild epilepsy. He taught history and coached cricket at a school in England. In 1940, he decided to return to Australia. He couldn't find a university teaching job right away due to the war. Instead, he taught history and coached cricket at Geelong Grammar School. Some of his famous students there included Rupert Murdoch.

While at Geelong, he started reading Australian history and literature. This led to his first published work about Australia. It was an open letter to the 19th-century Australian writer "Tom Collins" about the idea of mateship. This letter appeared in the magazine Meanjin.

In 1944, Clark returned to Melbourne University to finish his master's degree. This was important for getting a university job. He became a lecturer in politics and later in Australian History. He taught the university's first full-year course on Australian history. Many of his students became important historians or politicians, like Frank Crean and Geoffrey Blainey.

Clark felt that Australian history had not been told properly. He believed Australians had a past to be proud of. He was disappointed that historians often ignored ordinary Australians and their values like mateship and equality. He argued that Australia should be seen as important on its own, not just compared to Great Britain.

In 1948, Clark became a Senior Lecturer. However, as the Cold War began, he found the atmosphere in Melbourne difficult. He was criticized for defending his colleagues who were accused of having communist sympathies. In response, 30 of his students wrote a letter supporting him.

In 1949, Clark moved to Canberra. He became a professor of history at the Canberra University College. This college later became part of the Australian National University (ANU). He lived in Canberra for the rest of his life.

During the 1950s, Clark published two volumes of Select Documents in Australian History. These books helped students learn Australian history by providing many original documents. Critics today often see these books as some of his best work.

At this time, Clark was seen as a conservative historian. He disagreed with some "Old Left" historians who saw Australian history as leading to a socialist future. He challenged common ideas, for example, saying that the gold miners at Eureka were not revolutionaries but people hoping to get rich.

Writing A History of Australia

In the mid-1950s, Clark started a big project: writing a multi-volume history of Australia. He wanted to use historical documents but also share his own ideas about Australia's past. He traveled to places like Jakarta, London, and the Netherlands to find documents about Australia's discovery and early settlement. His wife, Dymphna, did much of the research in the Dutch archives.

Clark decided he wanted to write a lively story of Australian history. He focused on how the Australian environment affected European settlers in the 18th and 19th centuries. This was the start of his famous The History of Australia series.

The first volume came out in 1962. Five more volumes followed over the next 26 years, covering Australian history up to 1935. Clark was inspired by famous historians like Thomas Carlyle and Edward Gibbon. He believed that Australia's story offered important lessons for people. He also started to see history, including Australia's, as a tragedy.

A main idea in Clark's early volumes was the struggle between the harsh Australian land and the European values of the settlers. He focused on individuals and their challenges. He believed that many of his heroes had a "tragic flaw" that made their efforts difficult.

Clark's writing style was very colorful. He used references to the Bible and dramatic language. This made his books popular with the public, even though some historians criticized his lack of factual detail. He argued that the struggles between different beliefs in Australia led to a spiritual decline. He felt Australians became too focused on material things.

Some critics said Clark speculated too much about people's feelings and not enough about what they actually did. Others praised his storytelling and how he showed individual characters. Many readers enjoyed his narrative style and were not bothered by academic criticisms.

Visiting the Soviet Union

In 1958, Clark visited the Soviet Union for three weeks. He was a guest of the Soviet Union of Writers. He visited Moscow and Leningrad. He was interested in seeing the Bolshoi Ballet and museums. He also asked questions about Boris Pasternak, a writer who was in trouble with the Soviet government.

When he returned, he wrote articles that were published as a booklet called Meeting Soviet Man (1960). This book later led to accusations that Clark was too sympathetic to communism. However, he also criticized the dullness of Soviet culture and the greed of its government officials. He praised the Soviet state for providing for its people's basic needs. He also said that Vladimir Lenin was as important as Jesus, which was often quoted against him.

At the time, not everyone saw the book as pro-Soviet. A communist newspaper even criticized it for being too sympathetic to the West. Clark's political views were complex. He never joined a political party. However, from the mid-1960s, he supported the Australian Labor Party and admired leaders like Gough Whitlam.

Clark visited the Soviet Union again in 1970 and 1973. But in 1971, he protested outside the Soviet Embassy against the treatment of writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. In 1985, he also supported the Polish trade union Solidarity, which was against the Soviet system. He said he was not for revolution and felt torn between "radicalism and pessimism."

Later Volumes of The History of Australia

Volumes II and III of the History continued Clark's earlier themes. Volume II (1968) focused on conflicts between colonial governors and the first generation of white Australians. Volume III (1973) caused less discussion.

By the time Volume IV appeared in 1979, Clark's writing style and the public's reaction had changed. He focused more on the conflict between those who supported "King and Empire" and those who wanted an "Australian way of life." His strong dislike for the old Anglo-Australian upper class made some critics feel he was writing more like a political speaker than a historian.

In 1975, Clark gave the Boyer Lectures, which were broadcast and published as A Discovery of Australia. In these lectures, he shared his main ideas about history and life. He believed that history should celebrate life, even with its sadness.

Clark also responded to criticism about how he wrote about indigenous Australians. He admitted that when he started his History, he was thinking from a "British clock" perspective. Later, he wanted Australians to "build their own clock," starting 40 or 50 thousand years ago with the Aboriginal migration. He said he had only told part of the story, especially the "greatest human tragedy" of the meeting between white settlers and Aboriginal people.

In his final years, Clark faced health problems. He focused on finishing his History before he died. He completed Volume VI in 1986, which covered the years up to 1935. This volume highlighted the contrast between John Curtin (representing Australian nationalism) and Robert Menzies (representing the old Anglo-Australian ways). The book was released in 1987.

Criticism of His Work

By the 1970s, Clark was seen as a "left-wing" historian, even though his historical approach was not based on economic or class theories. This meant that left-wing thinkers often praised his work, while right-wingers criticized it.

His shift in public perception angered some conservative thinkers. He was accused of promoting a "Black armband view of history" (a term for a pessimistic view of Australia's past). These criticisms were often heated because many of the people involved had been friends for years.

Beyond politics, Clark's professional reputation as a historian also declined later in his life. The final two volumes of his History received less attention from other historians. This was not because they were "left-wing," but because they were seen as too wordy and repetitive, offering few new insights.

Some historians felt that Clark's focus on individuals and their flaws was less useful for understanding the more complex Australia of the late 19th and 20th centuries. His lack of interest in economic and social history also became a bigger issue for younger historians.

His Legacy

When Clark died in May 1991, he had become a national figure. People recognized his goatee beard, bush hat, and walking stick. His public image was as famous as his historical work. In 1988, his History was even turned into a musical, though it was not very successful.

After his death, in 1993, his former publisher, Peter Ryan, wrote an article criticizing the later volumes of Clark's History. Ryan claimed that the books lost their "scholarly rigour" over time. This article caused a big debate between left and right-wing critics.

In 1996, a newspaper claimed that Clark was a Soviet spy. They published parts of his security file. However, an investigation by the Australian Press Council found these claims to be false. Clark had received a bronze medallion during a visit to Moscow in 1970, not the Order of Lenin. The Press Council ruled that the newspaper had too little evidence for its claims.

Another criticism arose in 2007. It was discovered that Clark's account of walking the streets of Bonn the day after Kristallnacht (a violent event against Jews in Nazi Germany) was not entirely true. It was his future wife, Dymphna, who was there that day. However, Clark did arrive a short time later and saw the lasting effects, which deeply affected him.

Awards and Recognition

Clark received many honors during his life. He was appointed a Companion of the Order of Australia (AC) in 1975. He won several book awards, including the Moomba Book Award and the Henry Lawson Arts Award in 1969. He also received honorary doctorates from several universities. In 1980, he was named Australian of the Year.

After Dymphna Clark's death in 2000, their home in Canberra became Manning Clark House. It is now an educational center that hosts discussions and events about contemporary issues. Since 1999, Manning Clark House has held an annual lecture given by a distinguished Australian.

Several books have been written about Manning Clark's life and work, including "Manning Clark: A Life" by Brian Matthews. The Manning Clark Centre at the Australian National University was also named in his honor.

Images for kids

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |