Historiography of the United Kingdom facts for kids

The historiography of the United Kingdom is about how historians have researched and written about the past of the United Kingdom, Great Britain, England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales. It's like looking at how people have told the story of these places over time.

Contents

Medieval History Writers

The first important historian of Wales and England was Gildas, a monk from the 5th century. His book, De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae, talked about the fall of the Britons to Saxon invaders. He believed it was God's punishment.

Bede (673–735), an English monk, was super important in the Anglo-Saxon era. He used Gildas's work to write The Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Bede saw English history as one big story, centered around the Christian church.

Many other writers, called chroniclers, wrote detailed accounts of recent events. King Alfred the Great started the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in 893. Later, Jean Froissart (1333–1410) wrote Froissart's Chronicles, which is a key source for the first part of the Hundred Years' War.

Tudor and Stuart Times

Sir Walter Raleigh (1554–1618) was a soldier and writer who lived during the late Renaissance. While in prison, he started writing his History of the World. He used many sources and focused on ancient history and geography. King James I didn't like it, saying it was "too sawcie in censuring Princes" (too rude about kings).

Writing About the English Reformation

The English Reformation was a huge change when England broke away from the Catholic Church. Historians have argued about it for centuries!

Many different groups of historians have written about the Reformation:

- Protestant, Catholic, and Anglican historians often wrote from their own religious viewpoints.

- Whig historians saw the Reformation as a step forward, bringing England from the "Dark Ages" into modern times. They believed it led to more freedom and progress.

- Neo-Marxist historians focused on how economic changes, like the rise of new landowners, played a role.

Since the 1970s, scholars have looked at the Reformation in four main ways:

- Some, like Geoffrey Elton, focused on the political side. They looked at how policies were made and put into action by leaders like Thomas Cromwell.

- Others, like Geoffrey Dickens, focused on the religious side. They believed the Reformation, while started by leaders, also came from people's desires for religious change.

- Revisionists, like Christopher Haigh, looked at local records instead of just what the powerful people wrote. They found that the Reformation played out differently in everyday life in villages.

- Finally, historians like Patrick Collinson looked closely at the different religious groups, like the Calvinist Puritans, who had different ideas about the Church of England.

Newer studies pay more attention to local areas, Catholic views, and the different religious groups. They also focus less on King Henry VIII and more on other factors.

Puritans and the Civil War

The rise of the Puritans and the English Civil War are big topics in 17th-century English history.

Edward Hyde, a royal advisor, wrote an important history called The History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England (1702). He believed that God's plan influenced major events.

Samuel Rawson Gardiner (1820–1902) is considered the most important modern historian of the Puritan movement and Civil War. His detailed books cover the period from 1603 to 1660, looking at politics, government, religion, and ideas.

18th Century History Writers

The Enlightenment, a time of new ideas in Scotland and England, really helped history writing grow.

William Robertson

William Robertson, a Scottish historian, wrote a History of Scotland (1759) and The History of the Reign of Charles V (1769). He was very careful with his research and used many new documents. He was also one of the first to understand how big ideas shaped history.

David Hume

Scottish philosopher and historian David Hume published his History of England in six volumes starting in 1754. It covered history from Julius Caesar's invasion to 1688. Hume didn't just write about kings and wars; he also looked at culture, literature, and science. He believed that the search for liberty was the most important thing in the past.

Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon's famous book, Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–1789), set a very high standard for writing history. It also showed how important careful research was. Many later historians were inspired by Gibbon, especially those interested in the British Empire.

19th Century History Writers

Much of the history written in the 19th century was influenced by Romanticism, a movement that focused on emotion and imagination.

Whig History

Whig history was a popular way of looking at the past. It presented history as a steady journey towards more freedom and progress, ending with modern liberal democracy and constitutional monarchy. Whig historians often highlighted the growth of constitutional government, personal freedoms, and scientific progress.

The term "Whig history" was actually created by Herbert Butterfield in 1931 to criticize this approach. He argued that it made history seem like it was always getting better, which isn't always true. Whig historians often saw British history as a march of progress and viewed past political figures as heroes or villains based on whether they helped or hindered this progress.

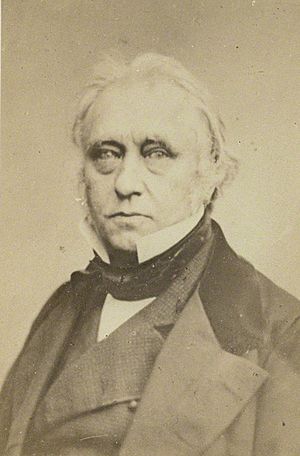

Macaulay's Influence

The most famous Whig historian was Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800–1859). His The History of England from the Accession of James II, published in 1848, was a huge success. His writing was powerful and confidently showed a progressive view of British history, where the country moved away from old ways to create a balanced government and freedom.

While some historians today don't read Macaulay as much, his book is still considered very important for understanding that period.

Local History

Before the 1960s, local history was very popular in Britain. It focused on the history of specific towns and counties. The Victoria County History project, which started in 1899, aimed to create a huge history book for each historic county in England.

Local history is still important today, with groups like the British Association for Local History helping people study their local past.

20th Century History Writers

Key Historians

- Thorold Rogers (1823–1890) studied economic history, especially farming and prices in England.

- French historian Élie Halévy (1870–1937) wrote a multi-volume history of England. He believed that religious nonconformity (people not following the main church) helped prevent a revolution like the one in France.

- G. M. Trevelyan (1876–1962) was a very popular historian. He combined good research with a lively writing style and a patriotic view of England's progress.

- Lewis Namier (1888–1960) had a big impact on how historians did research. He focused on looking at many individuals and their lives, rather than big themes.

- Herbert Butterfield (1900–1979) was known for his ideas about how history should be studied.

History Becomes a Profession

In the 20th century, history became a more professional field. Groups like the Royal Historical Society (founded 1868) and journals like The English Historical Review (started 1886) were created.

Universities like Manchester started offering PhD programs focused on original research. This was different from older universities like Oxford and Cambridge, which focused more on teaching undergraduates.

Class and Society

Marxist historiography is a way of studying history that focuses on social class and economic factors. Friedrich Engels wrote about the working class in England, which inspired socialist ideas.

R. H. Tawney was an important historian who looked at economic history, like how land was used and the connection between Protestantism and capitalism.

The "Storm over the gentry" was a big debate in the 1940s and 1950s. Historians argued about whether the rising class of wealthy landowners (the gentry) caused the English Civil War. Most historians later decided that the gentry's role wasn't the main reason.

Marxist Historians

A group of historians in the Communist Party of Great Britain became very influential. They focused on "history from below", looking at the lives of ordinary people and class structures.

- Christopher Hill (1912–2003) specialized in 17th-century English history, writing many books about Puritanism and the English Revolution.

- E. P. Thompson (1924–1993) wrote The Making of the English Working Class (1963), which looked at the forgotten history of the working class in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He argued that "class" was not just a structure but a changing relationship.

Other important Marxist historians included Eric Hobsbawm. However, this approach became less popular in the 1960s and 70s.

Rostow's Economic Stages

In 1960, American economic historian Walt Whitman Rostow wrote The Stages of Economic Growth. He suggested that countries go through five stages of economic growth, from traditional society to high mass consumption. This idea was an alternative to Marxist views and used British history as a comparison.

Since 1945

First World War Studies

Historians continue to be very interested in the First World War.

- Early studies focused on the military side.

- Later, scholars looked at the diplomatic reasons for the war.

- More recently, attention has shifted to the experiences of common soldiers and the role of the British Empire's colonies.

- Social history now looks at the home front, including women's roles and propaganda.

Important Historians (Post-1945)

- Arnold J. Toynbee (1889–1975) was famous for his huge 12-volume A Study of History, which looked at world history with a religious view.

- Keith Feiling (1884–1977) was known for his conservative view of history, supporting traditional institutions like the monarchy and the Church.

- A. J. P. Taylor (1906–1990) was a well-known historian and TV personality. He wrote important books on European diplomacy and 20th-century Britain. He was called "the Macaulay of our age" because of his clear writing and popular appeal.

- Hugh Trevor-Roper (1914–2003) was a leading essayist who enjoyed debates on historical topics, especially 16th and 17th-century England and Nazi Germany.

Political History

Political history, which looks at leaders and political parties, has always been a popular area of study.

Postwar Consensus

The post-war consensus is an idea used by historians to describe a period from 1945 to 1979. During this time, there was a general agreement among political parties on policies like a mixed economy, a broad welfare state (including the National Health Service), and full employment.

Historians like Paul Addison argued that this consensus was strong. However, in recent years, some historians have debated whether this agreement was as deep as once thought, pointing out that parties still had their differences.

Business History

Business history in Britain started to grow in the 1950s. Early studies looked at important companies and their role in developing industries. Later, historians focused on why British businesses might have lost their competitive edge after 1870.

More recently, business historians have looked at new topics like family businesses, how companies are run, marketing, and how British companies fit into the global economy.

Urban History

In the 1960s, historians started studying Victorian towns and cities in Britain. They looked at population changes, public health, the working class, and local culture. The cities themselves, including their buildings and spaces, became important topics.

Historians have always focused on London, but they also study smaller towns and cities, especially how they changed during the Industrial Revolution.

Deindustrialization

Historians are now looking at the topic of deindustrialization, which is when factories and mines closed down in the 1970s and 1980s. They study not only the economic reasons for these closures but also their social and cultural effects on working-class communities.

New Ways of Looking at History

Women's History

Women's history began to emerge in the 1970s. It focuses on the experiences and contributions of women throughout history, which had often been ignored by older historians.

History of Parliament

Since 1951, scholars have been working on a national "History of Parliament" project. This project involves detailed research into the lives of Members of Parliament (MPs) to understand the governing classes better.

History of the State

Historians are now exploring how the power of the state grew over time. They look at how the government collected information (like through censuses), how it managed money, and how it gained the loyalty of its people.

Global History

Some historians are now looking at a global history of Britain. This means seeing Britain's story not just as its own, but as connected to and shaped by events, processes, and people from all over the world, especially through its empires. This approach leads to new perspectives, like "Atlantic history", which connects Europe, Africa, and the Americas.

Digital History

Digital history is a new way to do research using computers and online tools. Projects like the Eighteenth Century Devon project have created online collections of old documents. Digital archives and search engines make it much easier for students and researchers to find and use historical sources like old newspapers.

See also

- Economic history of the United Kingdom

- Historians of England in the Middle Ages

- Historiography of the British Empire

- Historiography of the Poor Laws

- Historiography of the causes of World War I

- Historiography of Scotland

- History of Christianity in Britain

- History of England

- History of Northern Ireland

- History of Scotland

- History of Wales

- List of Cornish historians

- Military history of the United Kingdom

- Politics of the United Kingdom

- Timeline of British diplomatic history

- Timeline of Irish history

- Timeline of Scottish history

Special topics

- James Callaghan#Historiography, prime minister 1976-79

Important Historians

- Lord Acton (1834–1902), editor

- Robert C. Allen (born 1947), economic

- Perry Anderson (born 1938), Marxism

- Karen Armstrong (born 1944), religious

- William Ashley (1860–1927), British economic history

- Bernard Bailyn (born 1922), Atlantic migration

- The Venerable Bede (672–735), Britain from 55 BC to 731 AD

- Brian Bond (born 1936), military

- Arthur Bryant (1899–1985), Pepys; popular military

- Herbert Butterfield (1900–1979), historiography

- Angus Calder (1942–2008), Second World War

- I. R. Christie (1919–1998), 18th century

- Winston Churchill (1874–1965), world wars

- J.C.D. Clark (born 1951), 18th century

- Linda Colley (born 1949), 18th century

- R. G. Collingwood (1889–1943), philosophy of history

- Patrick Collinson (born 1929), Elizabethan England and Puritanism

- Julian Corbett (1854–1922), naval

- Maurice Cowling (1926–2005), 19th and 20th century politics

- Susan Doran, Elizabethan

- David C. Douglas (1898–1982), Norman England

- Eamon Duffy, religious history of the 15th–17th centuries

- Harold James Dyos (1921–78), urban

- Geoffrey Rudolph Elton, Tudor period

- Charles Harding Firth (1857–1936), political history of the 17th century

- Judith Flanders (born 1959), Victorian social

- Amanda Foreman (born 1968), 18th–19th centuries; Women

- Antonia Fraser, 17th century

- Edward Augustus Freeman (1823–1892), English politics

- James Anthony Froude (1818–1894), Tudor England

- William Gibson, ecclesiastical history

- Samuel Rawson Gardiner (1829–1902), political history of the 17th century

- Geoffrey of Monmouth (died c. 1154), England

- Lawrence Henry Gipson (1882–1970), British Empire before 1775

- George Peabody Gooch (1873–1968), modern diplomacy

- Andrew Gordon, naval

- John Richard Green (1837–1883), English

- Mary Anne Everett Green (1818–1895)

- John Guy (born 1949), Tudor era

- Edward Hasted (1732–1812), Kent

- Max Hastings (born 1945), military, Second World War

- J. H. Hexter, 17th century; historiography

- Christopher Hill (1912–2003), 17th century

- Gertrude Himmelfarb (born 1924), Victorian

- Harry Hinsley (1918–1998), British intelligence, World War 2

- Eric Hobsbawn (1917–2012), Marxist; 19th–20th centuries

- David Hume (1711–1776), six volume History of England

- Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon (1609–1674), English Civil Wars

- William James (naval historian), Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars

- George Hilton Jones III (1924–2008)

- David S. Katz, religious

- R.J.B. Knight (born 1944), naval

- David Knowles (1896–1974), medieval

- Andrew Lambert (born 1956), naval

- John Lingard (1771–1851), survey from Catholic perspective

- John Edward Lloyd (1861–1947), early Welsh history

- David Loades (born 1934), Tudor era

- Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay (1800–1859), The History of England from the Accession of James the Second

- Piers Mackesy (born 1924), military

- J. D. Mackie (1887–1978), Scottish

- Frederic William Maitland (1850–1906), legal, medieval

- Arthur Marder (1910–1980), 20th century naval

- Kenneth O. Morgan (born 1934), Wales; politics since 1945

- Lewis Namier, political history of the 18th century

- Charles Oman (1860–1946), 19th century military

- Bradford Perkins (1925–2008), diplomacy with U.S.

- J.H. Plumb (1911–2001), 18th century

- J. G. A. Pocock (born 1924), political ideas; early modern

- Roy Porter (1946–2002), social and medical

- F. M. Powicke (1879–1963), English medieval

- Andrew Roberts, Political biographies, 19th and 20th centuries

- N.A.M. Rodger, naval

- Stephen Roskill, naval

- A. L. Rowse (1903–1997), Cornish history and Elizabethan

- Conrad Russell, 17th century

- Dominic Sandbrook (born 1974), 1960s and after

- John Robert Seeley (1834–1895), political history; Empire

- Simon Schama (born 1945), surveys

- Jack Simmons (1915–2000), railways, topography

- Quentin Skinner, early modern political ideas

- Goldwin Smith (1823–1910), British and Canadian

- Richard Southern (1912–2001), medieval

- David Starkey (born 1945), Tudor era

- Frank Stenton (1880–1967), English medieval

- Lawrence Stone, society and the history of the family

- William Stubbs (1825–1902), law

- A.J.P. Taylor (1906–1990), 19th century diplomacy; 20th century; historiography

- E. P. Thompson (1924–1993), working class

- A. Wyatt Tilby (1880–1948), British diaspora

- George Macaulay Trevelyan (1876–1962), English history (many different periods)

- Hugh Trevor-Roper, Baron Dacre of Glanton, 17th century

- Walter Ullmann (1910–1983), medieval

- Paul Vinogradoff (1854–1925), medieval

- Charles Webster (1886–1961), Diplomatic

- Retha Warnicke (born 1939), Tudor history and gender issues

- Cicely Veronica Wedgwood (1910–1997), British

- Ernest Llewellyn Woodward (1890–1971), international relations

- Perez Zagorin (born 1920), 16th and 17th centuries

Organisations

- British Association for Local History

- Centre for Contemporary British History

- Centre for Metropolitan History

- Dictionary of National Biography

- Economic History Society

- Federation of Family History Societies

- Historical Association

- Historical Manuscripts Commission

- History of Parliament

- Institute of Historical Research

- Oral History Society

- Royal Historical Society

- Society of Antiquaries of London

- Society of Genealogists

- Victoria County History

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |