History of Wales facts for kids

The land we now call Wales (or Cymru in Welsh) has a very long history. People have lived here for at least 230,000 years! The first modern humans arrived around 31,000 BC. Since the last ice age ended about 9000 BC, people have lived in Wales continuously. We can find many signs of them from the Stone Age, New Stone Age, and Bronze Age.

During the Iron Age, the region was home to the Celtic Britons. They spoke a language called Brittonic. The Romans started conquering Britain in AD 43. They reached northeast Wales in 48 AD and took full control by 79 AD. The Romans left Britain in the 5th century. This allowed Anglo-Saxon groups to invade.

After the Romans left, the Brittonic language and culture began to split. Several different groups formed. The Welsh people were the largest of these groups. After the 11th century, they are usually talked about separately from other Brittonic-speaking people.

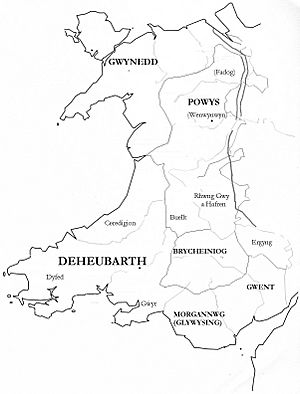

In the time after the Romans, many Welsh kingdoms appeared. These included Gwynedd, Powys, and Deheubarth. The most powerful ruler was called the "King of the Britons" or later, "Prince of Wales." Some rulers controlled other Welsh lands and even parts of western England. But no one could unite all of Wales for very long.

Fighting among themselves and pressure from the English, and later the Normans, slowly brought the Welsh kingdoms under English rule. In 1282, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd died. This led to King Edward I of England conquering the Principality of Wales. After this, the future king of England was given the title "Prince of Wales".

The Welsh fought back against English rule many times. The last big revolt was led by Owain Glyndŵr in the early 15th century. In the 16th century, King Henry VIII, who had Welsh family roots, passed laws. These "Laws in Wales Acts" aimed to make Wales a full part of the Kingdom of England.

Wales became part of the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. Then it joined the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801. Even with strong English influence, the Welsh kept their language and culture. In 1588, William Morgan published the first complete Welsh Bible. This was very important for the Welsh language.

The 18th century brought two big changes to Wales. The first was the Welsh Methodist revival, which made many people in Wales become nonconformist Protestants. The second was the Industrial Revolution. In the 19th century, especially in Southeast Wales, industries like coal and iron grew fast. This caused the population to boom.

Wales played a full part in World War One. In the 20th century, after World War Two, industries in Wales declined. At the same time, nationalist feelings grew stronger. The Labour Party became the main political force in the 1920s. Wales played a big role in World War Two, and its cities were bombed during the Blitz.

The nationalist party Plaid Cymru gained popularity from the 1960s. In 1997, Welsh voters said "yes" to having their own government. This led to the National Assembly for Wales being created in 1999. In May 2020, it was officially renamed Senedd Cymru, or the Welsh Parliament (simply Senedd). This showed that Wales had gained much more power to govern itself.

Contents

Ancient Wales: Early Humans and Farmers

The oldest human bone found in Wales is a Neanderthal jawbone. It was discovered in North Wales and is about 230,000 years old. Another famous find is the Red Lady of Paviland. This skeleton, found in 1823, is actually a young man. He lived about 33,000 years ago and was buried with jewelry and a mammoth skull. This is thought to be the oldest ceremonial burial in Western Europe.

After the last ice age, around 8000 BC, Wales looked much like it does today. Mesolithic hunter-gatherers lived here. The first farming communities started around 4000 BC, marking the beginning of the New Stone Age. During this time, people built many large stone tombs, called chambered tombs or cromlechs.

Metal tools first appeared in Wales around 2500 BC. First came copper, then bronze. The climate during the Early Bronze Age (around 2500–1400 BC) was warmer than it is now. Many ancient remains from this time are found in what are now cold uplands. The Late Bronze Age (around 1400–750 BC) saw better bronze tools. Much of the copper likely came from the Great Orme mine, where ancient mining was very active.

The earliest iron tool found in Wales is a sword from Llyn Fawr, dating to about 600 BC. People continued to build hillforts during the Iron Age. Wales has nearly 600 hillforts, which is over 20% of all those found in Britain. Important finds from this time include weapons, shields, and chariot parts from Llyn Cerrig Bach. Many of these items were broken on purpose, suggesting they were offerings to gods.

For a long time, people thought Wales was settled by many different groups moving in. But now, experts believe that the population stayed mostly the same over time. Studies of genetics suggest that people have lived in Wales continuously since the Stone Age. Historian John Davies believes that the Brythonic languages, spoken across Britain, developed from local people, not from new groups migrating in.

Roman Rule in Wales

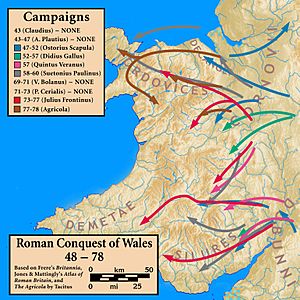

The Romans began conquering Wales in AD 48 and finished by 78 AD. Their rule lasted until 383 AD. Roman rule in Wales was mostly military. Only the southern coastal area, east of the Gower Peninsula, became more Romanized. The only Roman town in Wales, Caerwent, is in South Wales. Both Caerwent and Carmarthen became important Roman centers.

By AD 47, Rome had conquered southern and southeastern Britain. To conquer Wales, they launched several campaigns. These continued until 78 AD. The most famous part of Roman rule in Wales is the brave but unsuccessful resistance by two native tribes: the Silures and the Ordovices.

The Demetae tribe in southwest Wales seemed to make peace with the Romans quickly. There are no signs of war with them. Their land was not heavily covered with forts or roads. The Demetae were the only Welsh tribe to keep their homeland and name after Roman rule.

Wales had a lot of valuable minerals. The Romans used their advanced engineering to get large amounts of gold, copper, and lead. They also found smaller amounts of zinc and silver. When mines were no longer useful, they were left. Roman economic growth was mainly in southeastern Britain. Wales did not have big industries. This was because Wales lacked the right mix of materials, and its forests and mountains made industrial growth difficult.

The year 383 is important in Welsh history. In that year, the Roman general Magnus Maximus took all the troops and leaders from western and northern Britain. He used them to try and become emperor. He ruled Britain from Gaul (modern France). Since he left with the troops, he gave local power to local rulers. Welsh legends say he did exactly this.

A Welsh story, The Dream of Emperor Maximus, says he married a British woman. She asked for her father to rule Britain as a wedding gift. This story made it seem like the Romans officially gave power back to the Britons. Many medieval Welsh kings claimed Maximus as their ancestor.

After the Romans left, some Roman customs continued in southern Wales into the 5th century. Caerwent remained occupied. However, Carmarthen was likely abandoned in the late 4th century. Also, settlers from Ireland came to Wales in the late 4th century. It's unlikely they became Romanized.

Apart from Roman finds along the southern coast and the Romanized area around Caerwent, most Roman remains in Wales are military roads and forts.

Wales After Rome: The Age of Saints (411–700)

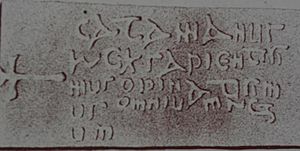

When the Roman soldiers left Britain in 410 AD, the different British states became self-governing. An old stone from Gwynedd shows that Roman influence continued. It mentions a "citizen" and "magistrate" from the late 5th or early 6th century. Many Irish settlers came to southwest Wales, and we find stones with Irish Ogham writing there.

Wales became Christian. The "age of the saints" (around 500–700 AD) saw many religious leaders, like Saint David, set up monasteries across the country.

One reason the Romans left was pressure from barbarian tribes from the east. These tribes, including the Angles and Saxons (who later became the English), could not easily enter Wales. But they slowly conquered eastern and southern Britain. In 616, at the Battle of Chester, the Welsh kingdoms were defeated by the Northumbrians. This battle likely cut off the land connection between Wales and other Brythonic-speaking areas in what is now Scotland and northern England. From the 8th century on, Wales was the largest of the three remaining Brythonic areas in Britain.

Wales was divided into several kingdoms. The biggest were Gwynedd in the northwest and Powys in the east. Gwynedd was the most powerful in the 6th and 7th centuries. Rulers like Cadwallon ap Cadfan even led armies into Northumbria. But after Cadwallon died, Gwynedd and other Welsh kingdoms mostly fought to defend themselves against the growing power of Mercia.

Early Medieval Wales: 700–1066

Powys, being the easternmost Welsh kingdom, faced the most pressure from the English. This kingdom originally reached into areas now in England. Its old capital, Pengwern, might have been modern Shrewsbury. These areas were lost to the kingdom of Mercia. The large earth wall called Offa's Dyke, built by King Offa of Mercia in the 8th century, may have marked an agreed border.

It was rare for one person to rule all of Wales during this time. This was partly because of the Welsh inheritance system. All sons, even illegitimate ones, received an equal share of their father's property. However, Welsh law also allowed for an "edling" (heir) to the kingdom to be chosen, usually by the king. Often, disappointed candidates would challenge the chosen heir.

The first ruler to control a large part of Wales was Rhodri Mawr (Rhodri The Great) in the 9th century. He was king of Gwynedd and expanded his rule to Powys and Ceredigion. After he died, his lands were divided among his sons. Rhodri's grandson, Hywel Dda (Hywel the Good), created the kingdom of Deheubarth in the southwest. By 942, he ruled most of Wales. He is known for writing down Welsh laws at a council in Whitland. These laws are still called the "Laws of Hywel." Hywel kept peace with the English. When he died in 949, his sons kept Deheubarth but lost Gwynedd.

Wales then faced more attacks from Vikings, especially Danish raids between 950 and 1000. In 987, Godfrey Haroldson took two thousand captives from Anglesey. The king of Gwynedd, Maredudd ab Owain, reportedly paid a large ransom to the Danes to free many of his people.

Gruffydd ap Llywelyn was the next ruler to unite most of the Welsh kingdoms. He was king of Gwynedd and by 1055, he ruled almost all of Wales. He even took parts of England near the border. However, he was defeated by Harold Godwinson in 1063 and killed by his own men. His lands were again split into the traditional kingdoms.

Wales and the Normans: 1067–1283

When the Normans conquered England in 1066, Bleddyn ap Cynfyn was the main ruler in Wales. He was king of Gwynedd and Powys. The Normans first succeeded in the south. William Fitz Osbern took over Gwent before 1070. By 1074, the Earl of Shrewsbury's forces were attacking Deheubarth.

Bleddyn ap Cynfyn's death in 1075 led to civil war. This gave the Normans a chance to take land in North Wales. In 1081, Gruffudd ap Cynan, who had just won the throne of Gwynedd, was captured by the Earl of Chester and Earl of Shrewsbury. This led to the Normans taking much of Gwynedd. In the south, William the Conqueror moved into Dyfed, building castles and mints. Rhys ap Tewdwr of Deheubarth was killed in 1093. His kingdom was taken and divided among Norman lords. It seemed the Norman conquest of Wales was almost complete.

However, in 1094, there was a general Welsh revolt against Norman rule. Slowly, territories were won back. Gruffudd ap Cynan eventually built a strong kingdom in Gwynedd. His son, Owain Gwynedd, and Gruffydd ap Rhys of Deheubarth won a big victory over the Normans in 1136. Owain became king of Gwynedd the next year and ruled until 1170. He used the disunity in England, where Stephen and Matilda were fighting for the throne, to expand Gwynedd's borders further east.

Powys also had a strong ruler, Madog ap Maredudd. But when he died in 1160, followed quickly by his heir, Powys split into two parts and never reunited. In the south, Gruffydd ap Rhys died in 1137. But his four sons, who all ruled Deheubarth, eventually won back most of their grandfather's kingdom from the Normans. The youngest, Rhys ap Gruffydd (The Lord Rhys), ruled from 1155 to 1197. In 1171, Rhys met King Henry II of England. They agreed that Rhys would pay tribute but keep his conquests. He was later named Justiciar of South Wales. In 1176, Rhys held a festival of poetry and song at his court, which is seen as the first recorded Eisteddfod.

From the power struggles in Gwynedd came one of the greatest Welsh leaders, Llywelyn ab Iorwerth. By 1200, he was the sole ruler of Gwynedd. By his death in 1240, he effectively ruled much of Wales. Llywelyn made his main base at Abergwyngregyn on the north coast. His son Dafydd ap Llywelyn followed him as ruler of Gwynedd. But King Henry III of England would not let him inherit his father's power elsewhere in Wales. Wars broke out in 1241 and 1245. Dafydd died suddenly in 1246 without an heir.

Llywelyn the Great's other son, Gruffudd, had died trying to escape from the Tower of London in 1244. Gruffudd had four sons. After some internal conflict, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (also known as Llywelyn, Our Last Leader) rose to power. The Treaty of Montgomery in 1267 confirmed Llywelyn's control over a large part of Wales. However, Llywelyn's claims clashed with King Edward I of England. War followed in 1277. Llywelyn had to agree to terms, and the Treaty of Aberconwy greatly limited his power.

War started again when Llywelyn's brother Dafydd ap Gruffydd attacked Hawarden Castle in 1282. On December 11, 1282, Llywelyn was killed near Builth Wells. His army was then destroyed. His brother Dafydd continued to resist, but it was hopeless. He was captured in June 1283 and executed. Wales effectively became England's first colony until it was fully joined with England by laws in the 1500s.

Conquest and Union: 1283–1542

After the Statute of Rhuddlan (1284) limited Welsh laws, King Edward I built many impressive stone castles to control Wales. In 1301, he gave his son and heir the title Prince of Wales. Wales became part of England, even though its people spoke a different language and had a different culture. English kings appointed a Council of Wales, sometimes led by the heir to the throne. This Council usually met in Ludlow, which was then part of the border area.

Welsh literature, especially poetry, continued to thrive. The lesser nobility now supported poets instead of the princes. Many consider Dafydd ap Gwilym, who lived in the mid-14th century, the greatest Welsh poet.

There were several rebellions. These included ones led by Madog ap Llywelyn in 1294–1295 and by Llywelyn Bren in 1316–1318. In the 1370s, Owain Lawgoch, the last male descendant of the Gwynedd ruling family, twice planned to invade Wales with French help. The English government had him assassinated in France in 1378.

In 1400, a Welsh nobleman, Owain Glyndŵr, revolted against King Henry IV of England. Owain defeated English forces many times and controlled most of Wales for a few years. He held the first Welsh Parliament and planned for two universities. Eventually, the king's forces regained control, and the rebellion ended. But Owain himself was never captured. His rebellion greatly boosted Welsh identity, and he had wide support.

After Glyndŵr's rebellion, the English parliament passed "Penal Laws against Wales." These laws stopped Welsh people from carrying weapons, holding public office, and living in fortified towns. These rules also applied to Englishmen who married Welsh women. The laws stayed in place after the rebellion, though they were slowly relaxed.

In the Wars of the Roses, which started in 1455, both sides used many Welsh troops. The main figures in Wales were the Earls of Pembroke: the Yorkist William Herbert and the Lancastrian Jasper Tudor. In 1485, Jasper's nephew, Henry Tudor, landed in Wales with a small force to claim the English throne. Henry was of Welsh descent, with princes like Rhys ap Gruffydd as ancestors. His cause gained much support in Wales. Henry defeated King Richard III of England at the Battle of Bosworth Field with an army that included many Welsh soldiers. He became King Henry VII of England.

Under his son, Henry VIII, the Laws in Wales Acts 1535-1542 were passed. These laws legally joined Wales with England. They ended the Welsh legal system and banned the Welsh language from official use. However, they also defined the border between England and Wales for the first time. They allowed Welsh areas to elect members to the English Parliament. These laws also removed legal differences between Welsh and English people, effectively ending the Penal Code.

Early Modern Wales

After King Henry VIII broke away from the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church, Wales mostly followed England in becoming Anglican. However, some Catholics tried to resist this change. They produced some of the first books printed in Welsh. In 1588, William Morgan created the first complete translation of the Welsh Bible. This Bible is one of the most important books in the Welsh language. Its publication greatly increased the importance and reach of the Welsh language and literature.

Wales was mostly Royalist during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms in the early 17th century. King Charles I of England got many soldiers from Wales, but no major battles happened there. The Second English Civil War began in 1648 when unpaid Parliamentarian soldiers in Pembrokeshire switched sides. Colonel Thomas Horton defeated the Royalist rebels at the battle of St. Fagans in May. The rebel leaders surrendered in July after a long siege of Pembroke.

Education in Wales was very poor during this time. The only education available was in English, but most people only spoke Welsh. In 1731, Griffith Jones started "circulating schools" in Carmarthenshire. These schools would stay in one place for about three months, then move to another. The teaching language in these schools was Welsh. By Griffith Jones' death in 1761, an estimated 250,000 people had learned to read in these schools across Wales.

The 18th century also saw the Welsh Methodist revival. This was led by Daniel Rowland, Howell Harris, and William Williams Pantycelyn. In the early 19th century, the Welsh Methodists left the Anglican church and formed their own denomination, now the Presbyterian Church of Wales. This also strengthened other nonconformist churches. By the mid-19th century, most people in Wales were nonconformist in religion. This was very important for the Welsh language, as it was the main language used in these churches. Sunday schools became a key part of Welsh life. They helped a large part of the population become literate in Welsh, which was vital for the language's survival since it wasn't taught in regular schools.

The late 18th century marked the start of the Industrial Revolution. Southeast Wales had iron ore, limestone, and large coal deposits. This meant that ironworks and coal mines quickly appeared there. Famous examples include the Cyfarthfa Ironworks and the Dowlais Ironworks at Merthyr Tydfil.

Modern Wales

The population of Wales doubled from 587,000 in 1801 to 1,163,000 in 1851. By 1911, it reached 2,421,000. Most of this growth happened in the coal mining areas, especially Glamorgan. Its population grew from 71,000 in 1801 to 1,122,000 in 1911. This increase was partly due to lower death rates and steady birth rates during the Industrial Revolution.

There was also a large migration of people into Wales during this time. The English were the largest group, but many Irish people also came. Smaller numbers of other groups, including Italians, moved to South Wales. In the 20th century, Wales received more immigrants from different parts of the British Commonwealth. African-Caribbean and Asian communities also added to the cultural mix, especially in Welsh cities. Many of these people identify as Welsh.

Wales in the Early 1900s

The modern history of Wales truly begins in the 19th century. South Wales became heavily industrialized with ironworks. Coal mining spread to the Cynon and Rhondda valleys from the 1840s. This led to a big increase in population. The social effects of industrialization caused armed uprisings against the mostly English owners.

Socialism grew in South Wales in the late 1800s. Religious nonconformism also became more political. The first Labour Member of Parliament (MP), Keir Hardie, was elected for a Welsh area in 1900.

The first ten years of the 20th century were a time of coal boom in South Wales. Population growth was over 20 percent. These changes affected the Welsh language. The number of Welsh speakers in the Rhondda valley dropped from 64 percent in 1901 to 55 percent ten years later. Similar trends happened elsewhere in South Wales.

Historian Kenneth O. Morgan describes the 1850-1914 period. He says it was a time of growing democracy and a thriving economy in the South Wales valleys. These valleys were the world's main coal-exporting area. There was also lively literature and a strong revival in the Eisteddfod (Welsh cultural festival). Nonconformist churches were very active, especially after a big religious revival in 1904–5. Overall, there was a strong sense of Welsh identity, with a national museum, library, and university leading the way.

Wales During the World Wars (1914-1945)

The World Wars and the time between them were difficult for Wales. The economy struggled, and there was a deep feeling of uncertainty. Many men eagerly volunteered for war service.

Morgan explains that 1914–45 brought a sudden and damaging change. World War One caused not only loss of life but also a collapse of economic life in South Wales. This led to much hardship. The war also saw the decline of Lloyd George’s Liberal Party and the national revival that happened before 1914. The Welsh-speaking world faced challenges. However, there was a strong rise in Anglo-Welsh poetry and prose, with writers like Dylan Thomas. World War Two brought more upheaval. But it also led to a revival of the South Wales economy, thanks to government support.

The Labour Party replaced the Liberals as the main party in Wales after World War One. This was especially true in the industrial valleys of South Wales. Plaid Cymru was formed in 1925, but it grew slowly at first and won few votes in elections.

Wales Since 1945

The period since 1945 has been one of renewal. There has been political growth under the Labour Party and unions. Economic growth has revived, bringing more wealth and social welfare. The most recent period has seen a strong movement towards political nationalism. Plaid Cymru has had some success. After a special commission, a big effort was made to give Wales more self-governance.

The coal industry steadily declined after 1945. By the early 1990s, only one deep coal mine was still working in Wales. The steel industry also saw a huge decline. The Welsh economy, like other developed countries, became more focused on the growing service sector.

In May 1997, a Labour government was elected. It promised to create devolved governments in Scotland and Wales. In late 1997, a vote was held in Wales, and people voted "yes." The Welsh Assembly was set up in 1999. It has the power to decide how the government budget for Wales is spent and managed.

The 2001 Census showed an increase in Welsh speakers. 21% of the population aged 3 and older spoke Welsh, up from 18.7% in 1991. This was a change from the steady decline seen throughout the 20th century. However, the 2011 census showed that the decline had started again. The number of Welsh speakers aged 3 and over in Wales decreased from 582,000 (20.8 percent) in 2001 to 562,000 (19.0 percent) in 2011.

The Government of Wales Act 2006 changed the National Assembly for Wales. It made it easier to give more powers to the Assembly. The Act created a government system where the executive (the government) is chosen from and answers to the legislature (the Assembly). After a successful vote in 2011, the National Assembly can now make laws, called Acts of the Assembly. It can do this on all matters in devolved areas without needing the UK Parliament's agreement. In the 2016 vote, Wales joined England in supporting Brexit, meaning leaving the European Union.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Gales para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Gales para niños

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |