Wales in the Early Middle Ages facts for kids

Imagine a time in Wales, long, long ago, right after the Romans left around the year 383. This period, known as the early Middle Ages in Wales, lasted until the mid-11th century. During this time, different parts of Wales slowly came together, forming stronger kingdoms. It was also when the Welsh language changed from an older form to what we now call Old Welsh. The border between Wales and England, which is still mostly the same today, also took shape during this era, often following a large earth wall called Offa's Dyke built in the late 700s. Wales would become a truly united country later, thanks to the family of a ruler named Merfyn Frych.

Life in Wales back then was mostly in the countryside. People lived in small villages called trefi. Powerful warrior leaders, known as aristocrats, controlled the land and the people living on it. Many people were tenant farmers or even slaves, and they had to obey the aristocrat who owned their land. People didn't think of themselves as one big "tribe." Instead, everyone, from the ruler to the slave, was defined by their family (called tud) and their personal standing (called braint). Christianity had arrived during the Roman times, and the Celtic Britons in Wales were Christians throughout this period.

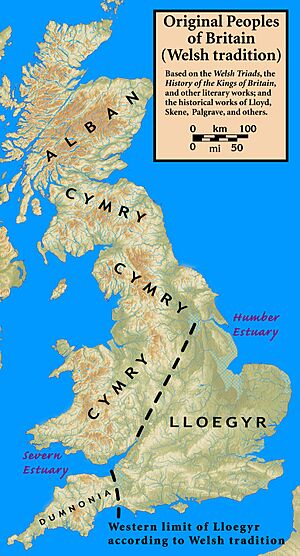

The story of the kingdom of Gwynedd starting in the 400s is almost like a legend. After that, there was a lot of fighting within Wales and with other British kingdoms in northern England and southern Scotland, known as the Hen Ogledd. Wales also became different from the British kingdom in the southwest, Dumnonia (which the Welsh called Cernyw). In the 600s and 700s, the Welsh kingdoms in the north and east fought many battles against the invading Anglo-Saxons from kingdoms like Northumbria and Mercia. During these struggles, the Welsh started calling themselves Cymry, which means "fellow countrymen." This was also when most of the other British kingdoms in northern England and southern Scotland disappeared, taken over by Northumbria.

Contents

How Wales Became a Nation

Wales as a country began to form because of the English who settled and tried to take over the island of Great Britain. In the early Middle Ages, people in Wales still saw themselves as Britons, meaning people from the whole island. But over time, the Welsh became separated by the sea and their English neighbors. It was these English neighbors who called the land "Wallia" and the people "Welsh."

Medieval Wales was not one unified country. It was divided into separate kingdoms that often fought each other, as well as their English neighbors. Not everyone in these communities was Welsh either. Evidence from place names and old artifacts shows that Viking or Norse people settled in places like Swansea, Fishguard, and Anglesey. Saxons also lived among the Welsh in areas like Presteigne.

The Norman invasion of England in 1066 changed everything. Soon after, the Normans began invading Wales. This new threat encouraged Welsh rulers to try and unite Wales into one strong state to fight back. Wales finally achieved this unity only when it was almost completely conquered. So, the threat of invasion actually helped create the nation of Wales.

Life in Early Medieval Wales

After the Romans left, Wales remained a rural land. Powerful warlords, who were local aristocrats, controlled the land. They also controlled the people who lived on that land. Many people were tenant farmers or slaves. They had to obey the aristocrat who owned the land where they lived. People didn't think of themselves as one big "tribe." Instead, everyone, from rulers to slaves, was defined by their family (the tud) and their personal standing (the braint).

Christianity had been brought by the Romans. The Celtic Britons in the land that would become Wales were Christians throughout this time. You can still see their influence in many Welsh place names that start with llan, which means a holy place or church.

Welsh kingdoms began to appear during this period. Their leaders often fought each other. This happened both within what would become Wales (like the kingdom of Gwynedd) and in the British kingdoms of northern England and southern Scotland (the Hen Ogledd). This was also when the language and way of life in Wales became different from the southwestern British kingdom of Dumnonia, which the Welsh called Cernyw. Cernyw later became Cornwall, and its language became Cornish.

The 600s and 700s were a time of constant fighting. The northern and eastern Welsh kingdoms fought against the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Northumbria and Mercia. During this struggle, the Welsh started calling themselves Cymry, meaning "fellow countrymen." Also, almost all the other British kingdoms in northern England and southern Scotland were taken over by Northumbria.

One king, Hywel Dda, almost united all of Wales. He was king of Deheubarth. In 942, he stepped in when Idwal Foel of Gwynedd was defeated by Edmund, King of England. Hywel Dda then took control of Gwynedd and Powys. This made him ruler of almost all of Wales, except for Morgannwg and Gwent. Hywel Dda also created Welsh law, which was used across Wales even after his kingdom was divided after his death.

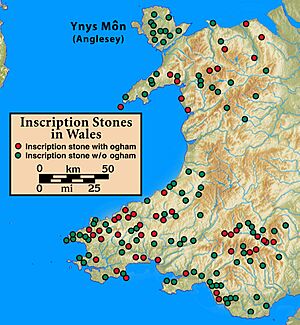

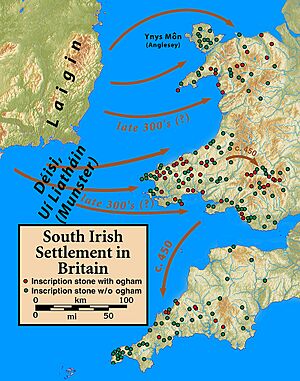

Irish Settlers in Wales

In the late 300s, people from southern Ireland came to Wales. These groups, like the Uí Liatháin and Laigin, settled in places like Dyfed. We don't know exactly why they came, but they left a lasting mark. There's no sign of war, and the mix of languages suggests they lived peacefully together. An old book from around 828, the Historia Brittonum, even says a Welsh king could invite foreigners to settle and give them land. This shows that Roman-era rulers had such power. These settlers don't seem to be connected to the Irish raiders (called Scoti) that the Romans wrote about.

Roman Influence on Wales

The most obvious signs of the Romans in Wales are their forts and roads. You can also find Roman coins and Latin writings near old Roman military sites. The southeastern coast of Wales shows more signs of Roman culture. Here, you can find the remains of Roman country houses called villas. Caerwent and a few other small towns, along with Carmarthen and Roman Monmouth, were the only "urban" Roman places in Wales.

This southeastern region was under Roman civilian rule from the mid-200s. The rest of Wales was under military rule throughout the Roman era. Many Latin words found their way into the Welsh language. For example, pobl (meaning "people") comes from Latin. However, the special words and ideas used in Welsh law during the Middle Ages were Welsh, not Roman.

Historians still discuss how much Roman influence lasted into the early Middle Ages in Wales. Wendy Davies, a historian, points out that even if some Roman ways of governing survived, they eventually changed into new systems that fit the time and place. They weren't just old Roman practices hanging on.

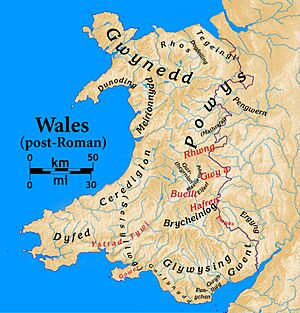

Early Welsh Kingdoms

We don't know the exact beginnings and sizes of the early kingdoms. The small kings of the 500s probably ruled tiny areas, maybe about 24 kilometers (15 miles) wide, often near the coast. Throughout this period, some families became stronger rulers, while new kingdoms appeared and then disappeared. It's possible that not every part of Wales was even part of a kingdom as late as the year 700.

Dyfed was the same land as the Demetae tribe shown on an old map from around 150 AD. Irish settlers arriving in the 300s linked the royal families of Wales and Ireland. Dyfed's rulers appear in old Irish stories and Welsh family trees. Its king, Vortiporius, was one of the kings criticized by a writer named Gildas around 540 AD.

We know more about the southeast, where the family of Meurig ap Tewdrig slowly gained land and power, connected to the kingdoms of Glywysing, Gwent, and Ergyng. But there's almost no information about many other areas. The first known king of Ceredigion was Cereticiaun, who died in 807. None of the kingdoms in central Wales can be proven to exist before the 700s. There are mentions of Brycheiniog and Gwrtheyrnion (near Buellt) in that era.

The early history of the north and east is a bit clearer. Gwynedd has a semi-legendary beginning with Cunedda arriving from Manau Gododdin in the 400s. An old gravestone from the 500s is the first known mention of the kingdom. Its king, Maelgwn Gwynedd, was also criticized by Gildas around 540 AD. There might have been kingdoms in Rhos, Meirionydd, and Dunoding in the 500s, all linked to Gwynedd.

The name Powys isn't definitely used before the 800s. But we can guess it existed earlier (maybe under a different name). This is because Selyf ap Cynan (died 616) and his grandfather are in old family trees as part of the later Powys kings. Selyf's father, Cynan Garwyn, appears in poems where he is described as leading successful raids across Wales.

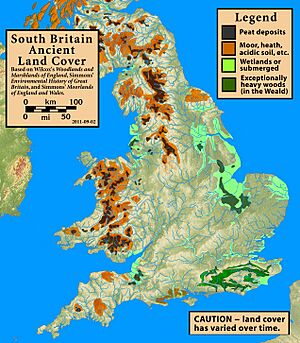

Wales's Landscape and Resources

Wales covers about 20,779 square kilometers (8,023 square miles). Much of it is mountainous with treeless moorlands and heath, and large areas of peat. It has about 1,200 kilometers (746 miles) of coastline and about 50 islands, with Anglesey being the largest. The weather today is wet and mild, with warm summers and mild winters. This was similar in the later Middle Ages, though it was cooler and much wetter earlier in the period. The southeastern coast was originally a wetland, but people have been reclaiming land there since Roman times.

Wales has deposits of gold, copper, lead, silver, and zinc. These metals have been mined since the Iron Age, especially during the Roman era. In Roman times, some granite and slate were quarried in the north, and sandstone in the east and south.

Native animals included large and small mammals like brown bears, wolves, wildcats, rodents, and many types of birds, fish, and shellfish.

Historians believe the human population in early medieval Wales was quite small compared to England. However, it's hard to get exact numbers.

How People Lived and Ate

Most of the good farming land is in the south, southeast, southwest, on Anglesey, and along the coast. It's hard to know exactly how people used the land back then because there isn't much evidence. We don't know how they decided which crops like wheat, oats, rye, or barley were best for their land and climate. Anglesey was special because it historically produced more grain than any other part of Wales.

People also raised animals like cattle, pigs, sheep, and a few goats. Oxen were used for plowing, donkeys for carrying things, and horses for transport. Sheep were less important than in later centuries because they didn't graze widely in the uplands until the 1200s. Animals were looked after by herders but were not kept in pens. They grazed on open land, and people moved them seasonally to different pastures. People also kept bees to make honey.

Society in Early Medieval Wales

Family and Kinship

Blood relationships were very important in medieval Wales, especially for showing noble birth. A family's right to rule depended on it. Long family trees were used to figure out fines and punishments under Welsh law. Different levels of family connection were important for different situations, all based on the cenedl (kindred or family group). The immediate family (parents and children) was very important. The pencenedl (head of the family within four generations on the father's side) had a special role. They represented the family in deals and had unique rights under the law. For serious matters like murder, even fifth cousins (descendants of a common great-great-great-great-grandfather) could be responsible for paying penalties.

Land and Political Areas

The Welsh described themselves by their land, not as a tribe. So, there was Gwenhwys (people of Gwent) and gwyr Guenti ("men of Gwent"). This was different from many Irish and Anglo-Saxon areas, where the land was named after the people living there.

The Welsh word for a political area was gwlad ("country"). It meant a "sphere of rule" with a specific territory. The Latin word regnum was similar, referring to a ruler's power that could grow or shrink. Rule was tied to a territory that could be held, protected, or expanded.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the Welsh used different words for rulers. The specific words changed over time. Latin texts used Latin terms, while Welsh texts used Welsh terms. Even the meaning of these terms changed. For example, brenin was a word for a king in the 1100s. But its original meaning was simply a person of high status. Kings were sometimes called overkings, but it's not clear if this meant they had specific powers or just high status.

Kingship and Power

Wales in the early Middle Ages had a society led by powerful warriors who owned land. After about 500 AD, kings with their own territories dominated Welsh politics. It was very important for a king to be seen as legitimate. They gained power through family inheritance or by being skilled warriors. A king had to be effective and associated with wealth, either their own or by giving it to others. The top kings were expected to be wise, perfect, and have far-reaching influence.

Old stories emphasized a king's military skills, like being a bold horseman, a good leader, and able to expand their borders and conquer new lands. They were also expected to be wealthy and generous. Religious writings stressed a king's duties, such as respecting Christian rules, providing defense and protection, catching thieves, and making fair judgments.

The relationship between people in this warrior society was based on loyalty and flexibility, not absolute power. Before the 900s, power was local, and its limits varied by region. There were at least two things that limited a ruler's power: the combined will of their people (their "subjects") and the authority of the Christian church. "Subjects" were people who paid taxes and provided military service when asked. In return, the ruler was supposed to protect them.

The Role of Kings

For much of the early medieval period, kings mostly had military duties. Kings fought wars and made judgments (after talking with local elders), but they didn't govern in the way we think of it today. From the 500s to the 1000s, the king traveled with an armed group of warriors on horseback. This personal military group was called a teulu. It was a "small, fast-moving, and close-knit group" that formed the main part of any larger army. The relationships between the king and his warriors were very personal. The practice of fosterage (raising someone else's child) made these bonds even stronger.

The Aristocracy

Power was held locally by families who controlled the land and the people on it. They had a higher sarhaed (penalty for insult) than common people. Records of their land deals, their involvement in local judgments, and their role in advising the king show their special status.

Welsh literature and law often mention the different levels of society that defined the aristocracy. A man's privilege was based on his braint (status), which came from birth or from holding an office. It also depended on the importance of his superior. For example, two men might both be uchelwr (high man), but a king was higher than a breyr (a regional leader). So, the legal payment for harming a king's servant (aillt) was higher than for harming a breyr's servant. Early sources said that nobility came from birth and job, not from wealth, which became important later.

The Common People

The common people included tenant farmers who inherited their land. They were not slaves or serfs, but they were not fully free. A gwas ("servant" or "boy") was a dependent person who was always in service but didn't have to do forced labor. This suggests there were bound dependents after the Roman era. We don't know how many people were free or owned their own land before the Norman conquest.

Slavery existed in Wales, just like everywhere else during this time. Slaves were at the very bottom of society. Hereditary slavery (being born into slavery) was more common than penal slavery (being enslaved as punishment). Slaves could be part of a payment in deals between higher-ranking people. It was possible for slaves to buy their freedom. An example of a slave being freed at Llandeilo Fawr is written in a note in an old book called the Lichfield Gospels from the 800s. We can only guess how many slaves there were.

Christianity in Early Wales

The religious life in Wales during the early Middle Ages was almost entirely Christian. Looking after the religious needs of the people was mostly done in rural areas, just like in other Celtic regions. In Wales, the clergy included monks, members of religious orders, and other non-monastic clergy. These groups appeared at different times and in different ways. There were three main orders: bishops (episcopi), priests (presbyteri), and deacons, plus several smaller ones. Bishops had some worldly power, but not always over a full diocese (a large church area).

Religious Communities

Monasteries existed in Britain in the 400s, though their exact beginnings are unclear. The Church seemed to be led by bishops and mostly made up of monasteries. We don't know the size of these religious communities. Old writings like Bede's work and the Welsh Triads suggest they were large, while the Lives of the Saints suggest they were small. However, these are not considered reliable sources. Different communities were most important within their local areas. The known sites are mostly on the coast, located on good land.

There are mentions of monks and monasteries in the 500s. For example, Gildas said that Maelgwn Gwynedd had originally planned to be a monk. From the 600s onwards, there are fewer mentions of monks but more frequent mentions of 'disciples'.

Church Buildings and Practices

Archaeological evidence includes the ruined remains of church buildings. We also find old inscriptions and the long cyst burials. These burials are typical of Christian Britons after the Roman era. They are graves lined with stones, have no grave goods, often face east-west, and date from a time before churches usually had cemeteries. They are different from Anglo-Saxon burials, which followed a different custom.

Records of transactions and legal references tell us about the status of the clergy and their institutions. Owning land was the main way religious communities supported themselves and earned income. They farmed (crops), herded animals (sheep, pigs, goats), had buildings like barns, and hired managers to oversee the work. Lands not next to the communities also provided income, like a landlord business. Lands owned by the clergy were free from the taxes demanded by kings and lords. They had the power of nawdd (protection from legal action) and were noddfa (a "nawdd place" or sanctuary). The Church's power was moral and spiritual. This was enough to make people respect their status and demand payment if their rights were violated.

Bede's View of Christianity

The idea of separate Anglo-Saxon and British ways of Christianity goes back to Bede. He described the Synod of Whitby (in 664) as a big battle between competing Celtic and Roman religious ideas. While the synod was important for England and settled some issues, Bede probably made it seem more significant to emphasize the unity of the English Church.

Bede also described Saint Augustine's meeting with seven British bishops and the monks of Bangor Is Coed (in 602–604). He showed the bishop of Canterbury as chosen by Rome to lead in Britain, while the British clergy were against Rome. He then added a prophecy that the British church would be destroyed. His made-up prophecy of destruction quickly came true with the massacre of the Christian monks at Bangor Is Coed by the Northumbrians around 615 AD, shortly after the meeting with Saint Augustine. Bede describes the massacre right after he tells the prophecy.

The 'Celtic' vs. 'Roman' Idea

After the Protestant Reformation and religious conflicts in Britain and Ireland, people started promoting the idea of a 'Celtic' church. This church was supposedly different from and against the 'Roman' church. It was said to have certain customs that were seen as wrong, especially how they calculated Easter, their tonsure (haircut for monks), and their church services. Scholars have pointed out that this idea was based on biased reasons and was not accurate. The Catholic Encyclopedia also explains that the Britons who used the 'Celtic Rite' in the early Middle Ages were still connected to Rome.

The Welsh Identity: Becoming 'Cymry'

The early Middle Ages saw the creation and adoption of the modern Welsh name for themselves, Cymry. This word comes from an older British word, combrogi, meaning "fellow-countrymen." It appears in a poem written around 633, and probably started being used as a self-description before the 600s. Historically, the word applied to both the Welsh and the British-speaking people of northern England and southern Scotland, known as the Hen Ogledd. This emphasized that the Welsh and the "Men of the North" were one people, separate from everyone else.

It took a while for the term Cymry to be fully accepted as the main written term in Wales. Eventually, it replaced older terms like Brython or Brittones. The term was not used for the Cornish people or the Bretons, even though they share similar heritage, culture, and language with the Welsh and the Men of the North.

All the Cymry shared a similar language, culture, and heritage. Their histories are filled with stories of warrior kings fighting wars. These histories are connected regardless of where they lived, much like the histories of neighboring Gwynedd and Powys are intertwined. Kings of Gwynedd even fought against other British opponents in the north. Sometimes, kings from different kingdoms worked together, as told in the old story Y Gododdin. Much of the early Welsh poetry and literature was written in the Old North by northern Cymry.

All the northern kingdoms and people were eventually absorbed into the kingdoms of England and Scotland. Their histories are now mostly just a small part of the histories of those later kingdoms. However, some traces of the Cymry past can still be seen. In Scotland, the remaining parts of the Laws of the Bretts and Scotts show British influence. Some of these laws were copied into the Regiam Majestatem, the oldest surviving written collection of Scots law. Here, you can find the 'galnes' (galanas), which is similar to a concept in Welsh law.

Images for kids

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |