Offa of Mercia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Offa |

|

|---|---|

A coin depicting Offa with the inscription Offa Rex Mercior[um] (Offa King of Mercia)

|

|

| King of Mercia | |

| Reign | 757 – 29 July 796 |

| Predecessor | Beornred |

| Successor | Ecgfrith |

| Died | 29 July 796 |

| Burial | Bedford |

| Spouse | Cynethryth |

| Issue Detail |

|

| House | Iclingas |

| Father | Thingfrith |

Offa was a powerful king of Mercia, an important kingdom in Anglo-Saxon England. He ruled from 757 AD until his death in 796 AD. Offa became king after a difficult period of civil war. He defeated another claimant, Beornred, to take the throne.

In his early years as king, Offa worked to strengthen his control over the central English regions. He also took advantage of problems in the kingdom of Kent and Sussex to become their main ruler, or "overlord." By the 780s, Offa had expanded Mercian power across most of southern England. He even made an alliance with Beorhtric of Wessex, whose marriage to Offa's daughter Eadburh helped secure Mercian influence. Offa also gained control over East Anglia. He even had its king, Æthelberht II of East Anglia, killed in 794, possibly because Æthelberht rebelled against him.

Offa was a Christian king, but he sometimes had disagreements with the Church. He famously convinced Pope Adrian I to divide the archdiocese of Canterbury into two parts. This created a new archdiocese at Lichfield. This change might have been because Offa wanted an archbishop who would crown his son, Ecgfrith of Mercia, as king. The ceremony, which was the first of its kind for an English king, happened in 787.

Many coins from Offa's time still exist today. They show beautiful pictures of him. Some even show his wife, Cynethryth. She is the only Anglo-Saxon queen ever shown on a coin. Offa's rule is seen by many historians as very important. He was one of the most powerful Anglo-Saxon kings before Alfred the Great.

Contents

- Understanding Offa's Time: Background and Sources

- Offa's Family and Early Life

- Offa's Rise to Power

- Controlling the Southeast: Kent and Sussex

- Expanding Influence: East Anglia, Wessex, and Northumbria

- Offa's Dyke and Wales

- Offa and the Church

- Connections with Europe

- How Offa Ruled

- Offa's Coins

- Offa's Importance

- Death and What Happened Next

- See also

Understanding Offa's Time: Background and Sources

In the early 700s, another Mercian king, Æthelbald of Mercia, was very powerful. He controlled most of the lands south of the River Humber. Mercia was a strong kingdom for a long time, from the mid-600s to the early 800s.

Offa was one of the most important rulers in early medieval Britain. However, no full biography of him written at the time has survived. One key source is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. This book tells the history of the Anglo-Saxons. It was written in Wessex, so it might favor Wessex kings over Mercian ones like Offa.

Another important source is charters. These were official documents that granted land to people or to the Church. They were signed by kings who had the power to give away land. These charters help us understand who was in charge and how power was shared. For example, a charter might show a local king signing as a "subking" under Offa's authority.

The monk Bede wrote a history of the English church, but it only goes up to 731. Still, it gives important background for Offa's time.

Offa's Dyke, a huge earth wall, is a great example of Offa's power. It shows he had many resources and could organize large projects. Other sources include letters from Alcuin, a scholar who worked for Charlemagne. These letters tell us about Offa's connections with other European rulers. Offa's coins also provide clues about his reign and his links to the Carolingian Empire.

Offa's Family and Early Life

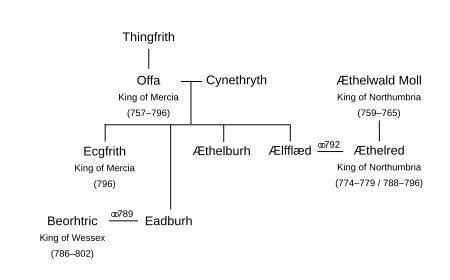

Offa's family tree shows he was related to Pybba of Mercia, an early Mercian king. Offa's grandfather, Eanwulf, was also related to King Æthelbald, who ruled before Offa. This suggests Offa and Æthelbald came from the same branch of the royal family. Offa even called Æthelbald his "kinsman" in one document.

Offa's wife was named Cynethryth. We don't know much about her family. They had a son, Ecgfrith of Mercia, and at least three daughters: Ælfflæd, Eadburh, and Æthelburh.

Offa's Rise to Power

King Æthelbald was killed in 757. After his death, a king named Beornred took the throne for a short time. However, the old records say that Offa "put Beornred to flight" and "sought to gain the kingdom of the Mercians by bloodshed." This means Offa fought to become king. He likely became king in 757 or 758.

This fight for the throne meant Offa had to regain control over Mercia's traditional areas, like the Hwicce and the Magonsæte. Charters from his early reign show that local kings in these areas were under Offa's rule. He also quickly gained control over the kingdom of Lindsey and the areas of London and Middlesex, which had been part of the East Saxons kingdom.

At first, Offa's power probably didn't reach far beyond Mercia's main territory. The strong control that Æthelbald had over southern England seemed to have disappeared during the civil war. It wasn't until 764 that Mercian power began to grow again, starting with influence in Kent.

Controlling the Southeast: Kent and Sussex

Offa took advantage of a difficult situation in Kent after 762. Kent often had two kings at once. After 762, several different kings appeared in Kent. In 764, Offa started granting land in Kent himself, with a Kentish king named Heahberht listed as a witness. This shows Offa's growing influence.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle mentions a battle between the Mercians and the people of Kent at Otford in 776. We don't know who won for sure. However, by 785, Offa's power in Kent was very clear. He treated Kent like any other part of his Mercian kingdom. This strong Mercian control lasted until Offa's death in 796.

Offa's involvement in Kent might be linked to the later exile of Egbert of Wessex to Francia. Egbert's father, Ealhmund, was a Kentish king. It's possible Offa wanted to take over Ealhmund's power in the southeast.

Evidence for Offa's control in Sussex also comes from charters. It seems that Sussex might have had several kings at once. Some historians believe Offa's authority was recognized in western Sussex early on. A chronicler from the 1100s said Offa defeated "the people of Hastings" in 771. This might mean he extended his rule over all of Sussex. It's also possible Offa gained full control of Sussex later, around the late 780s, similar to how he took over Kent.

Expanding Influence: East Anglia, Wessex, and Northumbria

In East Anglia, Beonna became king around 758. His early coins suggest he was independent from Mercia. Later, Æthelberht II of East Anglia became king in 779 and also issued his own coins. However, in 794, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states that "King Offa ordered King Æthelberht's head to be struck off." This means Offa had Æthelberht executed. It's likely Æthelberht rebelled against Offa's rule.

To the south, Cynewulf of Wessex became king of Wessex in 757. He took back some land that Mercia had conquered. Offa won an important battle against Cynewulf at Bensington in 779, regaining land along the River Thames. After Cynewulf was killed in 786, Offa might have helped Beorhtric of Wessex become the new West Saxon king. Beorhtric likely recognized Offa as his overlord. Offa's coins were used in Wessex, and Beorhtric didn't mint his own coins until after Offa died.

In 789, Beorhtric married Offa's daughter, Eadburh. The Chronicle says that Beorhtric "helped Offa because he had his daughter as his queen." This shows how Offa used marriage to strengthen his power. Eadburh was said to have had "power throughout almost the entire kingdom" of Wessex, likely due to her father's influence.

Offa's family connections also reached Northumbria. His daughter Ælfflæd married the Northumbrian king Æthelred I of Northumbria in 792. However, there's no evidence that Northumbria was ever under Mercian control during Offa's reign.

Offa's Dyke and Wales

Offa often fought with the different Welsh kingdoms. Records show battles between Mercians and Welsh at Hereford in 760. Offa also led campaigns against the Welsh in 778, 784, and 796.

The most famous structure linked to Offa is Offa's Dyke. This is a huge earth barrier that runs along the border between England and Wales. A monk named Asser wrote that Offa "had a great dyke built between Wales and Mercia from sea to sea." Most historians agree that Offa built it.

The dyke was likely built to create a strong barrier and allow Mercians to see into Wales. This suggests the Mercians could choose the best location for the dyke. The huge effort and cost to build it show that Offa had a lot of resources and power.

Offa and the Church

Offa was a Christian king. He was even praised by Alcuin, an advisor to Charlemagne, for his religious devotion. However, Offa had conflicts with Jænberht, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Jænberht had supported a Kentish king that Offa had problems with. Offa also claimed a monastery that Jænberht wanted.

In 786, Pope Adrian I sent special representatives, called papal legates, to England. This was the first time the Pope had sent such a mission since Augustine came to convert the Anglo-Saxons in 597. The legates met with Offa and other kings.

In 787, Offa successfully reduced the power of Canterbury. He created a new archdiocese at Lichfield. This new archdiocese included many of the central English territories. Hygeberht, who was already Bishop of Lichfield, became its first archbishop. He received a pallium, a special cloth that symbolized his authority, from Rome.

One possible reason for creating the new archdiocese was Offa's son, Ecgfrith of Mercia. After Hygeberht became archbishop, he crowned Ecgfrith as king. This ceremony happened within a year of Hygeberht becoming archbishop. It's possible that Archbishop Jænberht of Canterbury refused to crown Ecgfrith, so Offa needed another archbishop to do it. This was the first time an English king was consecrated (crowned in a religious ceremony) while his father was still alive. Offa likely wanted to copy the impressive ceremonies of Charlemagne's court in Francia.

Offa was also very generous to the Church. He founded several churches and monasteries, often dedicated to Saint Peter. He also promised a yearly gift of 365 mancuses to Rome. A mancus was a unit of money equal to thirty silver pennies. Offa also made sure that many religious houses would remain under the control of his wife or children after his death. This shows how rulers used religious institutions to support their families.

Connections with Europe

Offa had important diplomatic relationships with other European rulers, especially in the last 12 years of his reign. Alcuin wrote letters praising Offa for encouraging education.

Around 789, Charlemagne, the powerful Frankish emperor, suggested that his son marry one of Offa's daughters. Offa then asked if his son Ecgfrith could marry Charlemagne's daughter. Charlemagne was very angry about this and cut off contact with Britain. He even stopped English ships from landing in his ports. Eventually, diplomatic relations were restored.

In 796, Charlemagne wrote a letter to Offa. This letter is one of the first surviving diplomatic documents between England and another country. In it, Charlemagne called Offa his "brother." The letter discussed English pilgrims traveling in Europe and gifts exchanged between the two kings. It also mentioned exiles from England, like Eadberht Praen and Egbert of Wessex, who had found shelter at Charlemagne's court. This shows that Charlemagne sometimes supported people who were against Offa.

How Offa Ruled

Historians aren't completely sure how Mercian kings ruled during this time. One idea is that different branches of the royal family competed for the throne. Another idea is that powerful local families, called "dux" or "princeps" (leaders), helped kings come to power. Offa tried to make Mercian kingship more stable. He tried to remove rivals to his son Ecgfrith and reduced the power of local subject kings. However, he wasn't fully successful, as Ecgfrith only ruled for a few months after Offa's death.

There is evidence that Offa built a series of fortified towns called burhs. These might have included places like Bedford, Hereford, and Oxford. Besides being defensive, these burhs were probably important centers for trade and administration. They were early versions of the defensive network that Alfred the Great later used against the Danish invasions.

Offa also issued his own laws. We know this because Alfred the Great mentioned them in the introduction to his own law code. Alfred said he included the laws of Offa that he found "most just."

Offa's Coins

At the start of the 700s, small silver coins called sceattas were used. These coins often didn't have the king's name on them. Later in Offa's reign, new, heavier silver coins were made. These new coins were bigger and thinner. They almost always had Offa's name and the name of the "moneyer" (the person who made the coins) on them. Other kings in East Anglia, Kent, and Wessex also started making these new, heavier coins.

Some coins from Offa's time also have the names of the archbishops of Canterbury, Jænberht and later Æthelheard.

The medium-weight coins often show very artistic designs. The portraits of Offa on these coins are considered very beautiful and unique for Anglo-Saxon coins. They show him with different hairstyles and even wearing a necklace.

Offa's wife, Cynethryth, was the only Anglo-Saxon queen ever shown on coins. These coins were likely inspired by Byzantine coins that showed the empress.

Around 792–793, the silver coins were changed again. The pennies became even heavier, and a standard design without portraits was introduced.

Some gold coins from Offa's reign have also survived. One is a copy of an Abbasid dinar from 774. It has "Offa Rex" on one side and Arabic writing on the other. The person who made it probably didn't understand Arabic, as there are many mistakes. This coin might have been used for trade with Islamic Spain or as part of the yearly payment Offa promised to Rome.

We don't know for sure where all of Offa's coins were made. However, historians believe there were four mints (places where coins are made) in Canterbury, Rochester, East Anglia, and London.

Offa's Importance

Offa usually called himself "rex Merciorium," meaning "king of the Mercians." Sometimes he used "king of the Mercians and surrounding nations." Some documents even call him "Rex Anglorum," or "King of the English," which would show a very wide claim to power. However, some of these documents might not be real. The best evidence for him using "King of the English" comes from some coins, but it's not completely certain.

Many historians believe Offa was one of the greatest Anglo-Saxon kings, second only to Alfred the Great. His reign was once seen as a step towards a unified England. However, most historians today don't agree with this. As historian Simon Keynes said, "Offa was driven by a lust for power, not a vision of English unity; and what he left was a reputation, not a legacy." This means Offa wanted power for Mercia, not to create a single England. His military successes helped transform Mercia into a very powerful kingdom.

Death and What Happened Next

Offa died on July 29, 796. He might be buried in Bedford. His son, Ecgfrith of Mercia, became king after him. However, Ecgfrith only ruled for 141 days before he died.

A letter from Alcuin written in 797 suggests that Offa had worked very hard to make sure Ecgfrith would be king. Alcuin believed that Ecgfrith's death was a punishment for the "blood his father shed to secure the kingdom on his son." This means Offa likely removed other family members who could have claimed the throne. This strategy didn't work out for his family in the long run, as no close male relatives of Offa or Ecgfrith are known. Coenwulf of Mercia, who became king after Ecgfrith, was only distantly related to Offa's family.

See also

In Spanish: Offa de Mercia para niños

In Spanish: Offa de Mercia para niños

- Offacolus

- Vitae duorum Offarum

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |