Asser facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Asser |

|

|---|---|

| Bishop of Sherborne | |

| See | Sherborne |

| Appointed | c. 895 |

| Reign ended | c. 909 |

| Predecessor | Wulfsige |

| Successor | Æthelweard |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | c. 895 |

| Personal details | |

| Died | c. 909 |

Asser (died around 909) was a Welsh monk from St David's, a place in Dyfed, Wales. He later became a Bishop of Sherborne in England around the 890s.

Around 885, Alfred the Great asked Asser to join his group of smart people at court. Alfred was gathering learned men to help improve education in his kingdom. Asser was sick for a year at Caerwent, but then he agreed to join Alfred.

In 893, Asser wrote a book about Alfred's life. It was called Life of King Alfred. This book is the main source of information about King Alfred. It tells us much more about Alfred than we know about any other early English ruler. Asser also helped Alfred translate a book called Pastoral Care by Gregory the Great. He might have helped with other books too.

Some people used to say that Asser's book proved Alfred founded the University of Oxford. But we now know this is not true. A writer named William Camden added this idea to his version of Asser's book in 1603. For a while, some people even wondered if Asser's whole book was fake. But today, almost everyone agrees it is a real and important historical document.

Contents

Who Was Asser?

Asser was a Welsh monk who lived from at least 885 AD until about 909 AD. We don't know much about his early life. His name, Asser, probably comes from Aser, one of Jacob's sons in the Bible. Old Testament names were common in Wales back then.

Asser said in his book that he was a monk at St David's in the kingdom of Dyfed, in south-west Wales. He grew up there and became a priest there. He also mentioned that Nobis, a bishop of St David's who died around 873, was a relative of his.

How Alfred Recruited Asser

Most of what we know about Asser comes from his book about King Alfred. Asser wrote about how Alfred asked him to join his court as a scholar. King Alfred really valued learning. He brought together smart men from all over Britain and Europe to create a center for learning at his court.

We don't know how Alfred found out about Asser. But Alfred had control over parts of south Wales. Several Welsh kings, including Hyfaidd of Dyfed (where Asser's monastery was), had agreed to follow Alfred in 885. It's possible that Alfred's connection with these Welsh kings led him to hear about Asser.

Asser first met Alfred at a royal estate in Dean, Sussex. Asser mentions one clear date in his story: on November 11, 887, Alfred decided to learn to read Latin. Counting back from this, it seems Asser was probably asked to join Alfred's court in early 885.

Asser asked for time to think about Alfred's offer. He felt it wouldn't be fair to leave his current job just for fame. Alfred agreed and suggested Asser could spend half his time in Wales and half with him. Asser agreed to this plan.

However, when Asser returned to Wales, he got a fever. He was sick for over a year at the monastery of Caerwent. Alfred wrote to him to find out why he was delayed. Asser replied that he would keep his promise once he got better. When he did recover in 886, he agreed to divide his time between Wales and Alfred's court. Other monks at St David's supported this. They hoped Asser's influence with Alfred would protect them from King Hyfaidd, who often attacked their monastery.

Asser's Time at Court

Asser joined other famous scholars at Alfred's court. These included Grimbald and John the Old Saxon. They all probably arrived at Alfred's court around the same time. Asser's first long stay with Alfred was at a royal estate called Leonaford, likely from April to December 886. We don't know exactly where Leonaford was. Some think it was Landford in Wiltshire. Asser wrote that he read books aloud to the king there.

On Christmas Eve, 886, Alfred gave Asser some monasteries. These were Congresbury and Banwell. He also gave Asser a silk cloak and some incense. Alfred then let Asser visit his new properties and return to St David's.

After this, Asser seemed to split his time between Wales and Alfred's court. He didn't write much about his time in Wales. But he mentioned visiting places in England. These included the battlefield at Ashdown, Cynuit (Countisbury), and Athelney. It's clear Asser spent a lot of time with Alfred. He said he often met Alfred's mother-in-law and saw Alfred hunting many times.

Becoming a Bishop

Between 887 and 892, Alfred gave Asser the monastery of Exeter. Asser later became the Bishop of Sherborne. We don't know the exact year he became bishop. His predecessor, Wulfsige, was still bishop in 892. Asser first appeared as Bishop of Sherborne in 900. So, he must have become bishop sometime between 892 and 900.

Asser was already a bishop before he became Bishop of Sherborne. This is known because Wulfsige received a copy of Alfred's Pastoral Care. In that book, Asser is already called a bishop.

It's possible Asser was a helper bishop within the Sherborne area. But he might have been a bishop of St David's too. A writer named Giraldus Cambrensis listed him as a bishop of St David's. Asser himself wrote that bishops of St David's were sometimes kicked out by King Hyfaidd. He added, "he even expelled me on occasion." This suggests Asser was indeed a bishop of St David's.

Asser's Book: The Life of King Alfred

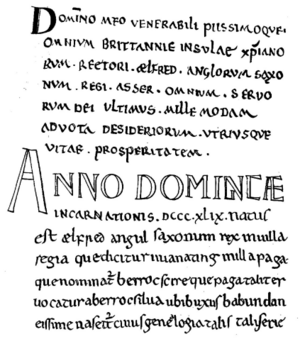

In 893, Asser wrote his famous book about Alfred. Its Latin title is Vita Ælfredi regis Angul Saxonum, which means The Life of King of the Anglo-Saxons Alfred. We know the date because Asser mentioned Alfred's age in the book. The book is less than 20,000 words long. It is one of the most important sources of information about Alfred the Great.

Asser used many different texts to write his book. He was likely familiar with other biographies, like those about Louis the Pious. He also knew Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, a history of the English church. He used a Welsh source called the Historia Brittonum. He also used the Life of Alcuin and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

About half of Asser's book is a translation of parts of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle from 851 to 887. But Asser added his own thoughts and details about Alfred's life. He also included information about events after 887. He shared his general opinions about Alfred's character and his time as king.

Some people have criticized Asser's writing style. They say his sentences are sometimes confusing. He used many old and unusual words. This made his writing sound fancy, which was common for writers in England and Ireland at that time. He also used some words that were common in Frankish (French) Latin. This might mean he studied in France, or he learned these words from French scholars at Alfred's court.

Asser's book ends suddenly without a conclusion. It's thought that the book is an unfinished draft. Asser lived for another 15 or 16 years, and Alfred lived for another six. But no events after 893 are recorded in the book.

The book might have been written for a Welsh audience. Asser took care to explain English places. He often gave an English name and then its Welsh equivalent, like for Nottingham. Since Alfred had only recently gained control over south Wales, Asser might have wanted to show Welsh readers how great Alfred was. This could help them accept Alfred's rule. However, it's also possible Asser just liked studying word origins. Or maybe he had Welsh readers in his own household. Some parts of the book, like supporting Alfred's building of forts, suggest it was also for an English audience.

Asser's book doesn't mention any fights or disagreements within Alfred's own rule. But he does say that Alfred had to punish people who were slow to obey his orders to build forts. This shows that Alfred did have to make people follow his commands. Asser's book is very positive about Alfred. But since Alfred was alive when it was written, it probably doesn't have big factual mistakes.

Asser's book is the main source for Alfred's life. But it also gives information about other historical times. For example, he tells a story about Eadburh, the daughter of King Offa. She married Beorhtric, king of the West Saxons. Asser said she acted "like a tyrant." He also said she accidentally poisoned Beorhtric while trying to murder someone else. He ended by saying she died as a beggar in Pavia.

Copies of The Life of King Alfred

The original copy of Asser's book didn't seem to be widely known in medieval times. Only one copy is known to have survived until modern times. It was called Cotton MS Otho A xii. It was part of the Cotton library. This copy was written around the year 1000. Sadly, it was destroyed in a fire in 1731.

The book might not have been copied much because Asser didn't finish it. However, parts of Asser's book appear in other old writings. This suggests that some early writers had access to versions of Asser's work.

- Byrhtferth of Ramsey included large parts of it in his historical work, Historia Regum. He wrote this in the late 900s or early 1000s.

- The writer of the Encomium Emmae (written in the early 1040s) seemed to know Asser's book.

- Florence of Worcester, a writer from the early 1100s, included parts of Asser's book in his own history.

- An unknown writer at Bury St Edmunds used material from a version of Asser's book. This version was slightly different from the Cotton manuscript.

- Giraldus Cambrensis quoted an event from Asser's work that happened during the time of King Offa. This event is not in the copies of Asser's book that we have today. It's possible Giraldus had a different copy of Asser's work. Or he might have been quoting another book by Asser that we don't know about. It's also possible Giraldus made up the reference to Asser to support his story. Giraldus is not always seen as a completely reliable writer.

The Cotton manuscript itself had a complicated history. It was owned by John Leland in the 1540s. It probably became available after many monasteries were closed and their property was sold. It was later owned by Matthew Parker. By 1621, it was in the library of Robert Cotton.

The Cotton library moved several times. On October 23, 1731, a fire broke out. The Cotton manuscript of Asser's Life was destroyed.

Because of this fire, we know the text of Asser's book from many different sources. Several copies had been made of the Cotton manuscript. Also, a copy of the first page had been made and published. These copies, along with the parts used by other early writers, have helped historians put the text back together.

Many versions of The Life have been published, both in Latin and in English. A very important version was published in 1904 by W. H. Stevenson. It's called Asser's Life of King Alfred, together with the Annals of Saint Neots erroneously ascribed to Asser. This is still the main Latin text used today. It was translated into English in 1905. A more recent and important translation is Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred and Other Contemporary Sources by Simon Keynes and Michael Lapidge.

The Oxford University Story

In 1603, a historian named William Camden published a version of Asser's book. In his version, there was a story about scholars at Oxford. It said that Grimbald visited them:

In the year 886, the University of Oxford began... John, a monk, taught logic, music, and arithmetic. And John, another monk, taught geometry and astronomy to King Alfred.

There is no other evidence for this story. Camden's version was based on an earlier copy, but other copies of that same manuscript don't have this part. We now know that Camden added this story himself. The idea that Alfred founded Oxford University first appeared in the 1300s. Older books about Alfred the Great often include this story. For example, Jacob Abbott's 1849 book Alfred the Great says that "One of the greatest and most important of the measures which Alfred adopted for the intellectual improvement of his people was the founding of the great University of Oxford."

Was Asser's Book a Forgery?

In the 19th and 20th centuries, some scholars thought Asser's book about King Alfred was not real. They thought it was a fake. A famous historian named V.H. Galbraith claimed in 1964 that the book had mistakes that meant it couldn't have been written when Asser was alive.

For example, Asser used the title "rex Angul Saxonum" ("king of the Anglo-Saxons") for Alfred. Galbraith said this title wasn't used until the late 900s. Galbraith also said that Asser's use of "parochia" for Exeter was a mistake. He thought it meant "diocese" (a bishop's area), and the bishopric of Exeter wasn't created until 1050. Galbraith believed the real author was Leofric, who became Bishop of Devon and Cornwall in 1046. Galbraith thought Leofric wrote it to make his new bishopric at Exeter seem older and more important.

However, the title "king of the Anglo-Saxons" actually does appear in royal documents from before 892. And "parochia" doesn't always mean "diocese." It can just mean the area a church or monastery has power over. Also, there are other reasons why Leofric probably wasn't the forger. Leofric wouldn't have known enough about Asser to write a believable fake. Plus, the Cotton manuscript is from around 1000. And parts of Asser's book were used in other early works that were written before Leofric's time.

Most historians now agree that Galbraith's arguments were wrong. Dorothy Whitelock showed this in her lecture in 1967, called Genuine Asser.

More recently, in 2002, Alfred Smyth argued that the book was a fake written by Byrhtferth. He based his idea on comparing the words Byrhtferth and Asser used in Latin. Smyth thought Byrhtferth wanted to use Alfred's fame to help the Benedictine monk reform movement in the late 900s. But most historians have not found this argument convincing. Few historians today doubt that Asser's book is real.

Other Works and Death

Besides The Life of King Alfred, Asser is also known for helping Alfred. Alfred said Asser was one of several scholars who helped him translate Pope Gregory I's Regula Pastoralis (Pastoral Care). A historian named William of Malmesbury, writing in the 1100s, believed Asser also helped Alfred translate a book by Boethius.

The Annales Cambriae, which are Welsh historical records, say that Asser died in 908. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records his death around 909 or 910. It says: "Here Frithustan became bishop in Winchester, and after that Asser, who was bishop at Sherborne, departed." Because different old writers started the new year on different dates, Asser's death date is usually given as 908/909.

See Also

Images for kids

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |