Cotton library facts for kids

The Cotton Library is a super important collection of old books and papers that belonged to Sir Robert Bruce Cotton (1571–1631). He was a collector who loved old things. His collection was one of the main groups of items that started the British Museum in 1753. Today, it's a huge part of the British Library's collection of old manuscripts.

Sir Robert Cotton came from a family in Shropshire. Many valuable old manuscripts from monasteries were scattered after the Dissolution of the Monasteries (when monasteries were closed down). Many people didn't know how important these old writings were. Sir Robert was great at finding, buying, and saving these ancient documents.

Important thinkers of his time, like Francis Bacon and Walter Raleigh, used Sir Robert's library. His library is special because it saved the only copies of famous works. These include Beowulf, The Battle of Maldon, and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

Sadly, in 1731, a fire badly damaged the collection. Thirteen manuscripts were completely lost, and about 200 others were seriously hurt. For example, the original text of The Battle of Maldon was totally burned. Luckily, copies of some important Anglo-Saxon manuscripts had already been made.

Contents

History of the Collection

How the Library Started

When monasteries were closed down a long time ago, many official records and important papers were not kept well. They were often held by private people, ignored, or even destroyed.

The Cotton family was well-known in Shropshire. Sir Robert Cotton managed to get over a hundred books of official papers. His house and library were very close to the Houses of Parliament by 1622. It became a valuable place for scholars and politicians to meet and share ideas.

These old documents were very important because they held clues about how the country was run. At the time, there were big arguments between the king and Parliament. Sir Robert knew his library was important for everyone. He let people use it freely. However, this made the government unhappy.

In 1629, Sir Robert was arrested because a pamphlet he shared was thought to be dangerous. The library was closed because of this. Sir Robert was released later, but the library stayed closed until after he died. It was given back to his son, Sir Thomas Cotton, in 1633.

Sir Robert's library included his collection of books, manuscripts, coins, and medals. After he died, his son, Sir Thomas Cotton (who died in 1662), and his grandson, Sir John Cotton (who died in 1702), continued to take care of and add to the collection.

Given to the Nation

Sir Robert's grandson, Sir John Cotton, gave the Cotton Library to Great Britain when he died in 1702. Back then, Great Britain didn't have a national library. So, the Cotton Library became the start of what is now the British Library.

An old law from 1700, called the British Museum Act, talked about the library. It said that Sir Robert Cotton had spent a lot of money and effort to collect these very useful manuscripts. It also said that his son and grandson had carefully kept and added to the library. Sir John Cotton wanted the library to stay in his family's name. He wanted it to be kept for the public to use and enjoy.

Later, in 1706, another law helped make sure the collection was safe. The books were moved from Cotton House, which was falling apart. They went to a few different places to keep them safe. From 1707, the library also held the King's own collection of books.

The Ashburnham House Fire

On October 23, 1731, a fire started at Ashburnham House. Thirteen manuscripts were completely lost, and over 200 others were badly damaged by fire and water. A scholar named Richard Bentley famously saved the very valuable Codex Alexandrinus by carrying it out under his arm!

The manuscript of The Battle of Maldon was destroyed. The Beowulf manuscript was also badly damaged. Another important book, the Byzantine Cotton Genesis, was severely hurt. One of the original copies of the 1215 Magna Carta was shriveled by the fire, and its seal melted.

Arthur Onslow, who was in charge of the House of Commons, helped lead a big effort to fix the damaged books. Copies of some lost works had been made before the fire. Many damaged ones could be fixed later. More recently, new technology like special photography has helped experts at the British Library read parts of the old manuscripts that were unreadable before.

British Museum and Library

In 1753, the Cotton Library was moved to the new British Museum. This happened because of a law that created the museum. At the same time, the Sloane and Harley collections were also added. These three collections became the "foundation collections" of the museum. The King's Royal manuscripts were given in 1757.

In 1973, all these collections moved again to the newly created British Library. The British Library still organizes the Cottonian books using the unique system Sir Robert Cotton created.

How the Library Was Organized

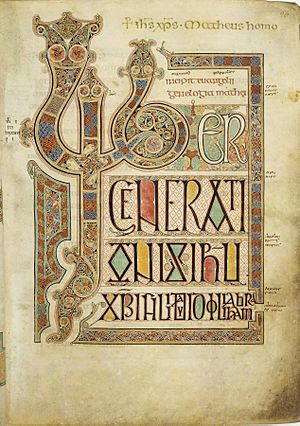

Sir Robert Cotton organized his library in a very interesting way. He arranged his books based on where they were in his room. Each bookcase had a bust (a sculpture of a head and shoulders) of a famous historical person on top. These included Augustus Caesar, Cleopatra, Julius Caesar, and Nero.

He had fourteen busts in total. His system used the bust's name, then a shelf letter, and then a volume number. For example, "Cotton Vitellius A.xv" means "Under the bust of Vitellius, on the top shelf (A), and it's the fifteenth book." This is how the book containing Beowulf is still known. "Cotton Nero A.x" means "Go to the bust of Nero, top shelf, tenth book." This is where the Pearl poem is found.

The manuscripts are still listed by these special names in the British Library today.

A scholar named Colin Tite thinks this system might not have been fully used until 1638. However, notes suggest Sir Robert planned to use this system before he died in 1631. He was probably stopped when the library was closed in 1629.

The first printed list of the Cotton Library's books was published in 1696 by Thomas Smith, who was the librarian for Sir John Cotton. The official list of the library's contents was published in 1802 by Joseph Planta. This was the main guide until modern times.

See also

- British Library

- Harleian Collection

- List of manuscripts in the Cotton library

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |