Beonna of East Anglia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Beonna |

|

|---|---|

Coin of Beonna, now in the British Museum

|

|

| King of the East Angles | |

| Reign | 749 – around 760 jointly with Alberht and possibly Hun |

| Predecessor | Ælfwald |

| Successor | Æthelred I |

Beonna (also known as Beorna) was a king who ruled East Anglia starting in the year 749. He is famous because his coins were the first from an East Anglian king to show both the ruler's name and his title. We don't know exactly when Beonna's rule ended, but it was probably around 760.

Historians think he might have shared his kingdom with another ruler named Alberht. There might even have been a third ruler named Hun. However, not all experts agree on these dates or how he ruled. Some believe he ruled alone and was free from the control of the powerful kingdom of Mercia from about 758.

We don't know much about Beonna's life or his time as king. This is because no written records from that period in East Anglian history have survived. The very few old writings that mention Beonna only briefly talk about him becoming king or ruling. Until recently, it was hard to know if these mentions were true.

But since 1980, many of Beonna's coins have been found. These coins prove that he was a real historical figure. They have also helped experts learn about the economy and languages used in East Anglia. They show how East Anglia was connected to other parts of England and northern Europe during Beonna's reign. The coins also give clues about who Beonna was and how he ruled.

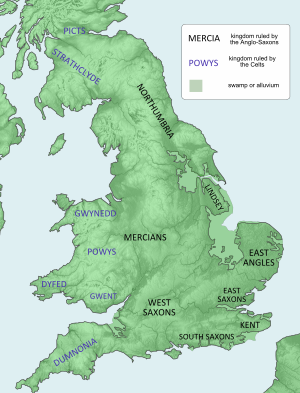

What was East Anglia like?

Compared to other big kingdoms like Northumbria, Mercia, and Wessex, we have very little reliable information about the kingdom of the East Angles. Historians like Barbara Yorke believe this is because Viking raids later destroyed the kingdom's monasteries. These raids also caused the main church centers (called episcopal sees) to disappear.

Before Beonna, King Ælfwald of East Anglia ruled East Anglia for 36 years. He died in 749. During Ælfwald's rule, East Anglia grew steadily and was stable. However, it was under the control of the powerful Mercian king Æthelbald. Æthelbald ruled Mercia from 716 until he was killed by his own men in 757. Ælfwald was the last king from the Wuffingas family. This family had ruled East Anglia since the 500s.

Who was King Beonna?

Historians know Beonna was a king of the East Angles because of a few old written sources. One source is a book from the 1100s called Historia Regum. It says that after Ælfwald died, "Hunbeanna and Alberht divided the kingdom of the East Angles between themselves." This book is thought to have been put together by Symeon of Durham. But most experts now agree that much of it was written by Byrhtferth of Ramsey around the late 900s.

Another source is a passage from a 12th-century book called Chronicon ex chronicis. It was once believed to be written by Florence of Worcester. This book stated that "Beornus" was king of the East Angles. A list of kings in the same book also says: "During the reign of Offa, king of the Mercians, Beonna reigned in East-Anglia, and after him Æthelred..."

The book The Flowers of History, written by Matthew Paris in the 1200s, also mentions Beonna. For the year 749, it says: "Ethelwold, king of the East Angles, died, and Beonna and Ethelbert divided his dominions between them."

Historians H. M. Chadwick and Dorothy Whitelock both suggested that the name Hunbeanna should be split into two names: Hun and Beanna. This would mean the kingdom might have been divided among three rulers. Steven Plunkett thinks the name Hunbanna might have been created by a scribe who made a mistake while writing.

It's possible that Alberht and Beonna never ruled together. Most historians agree that Alberht and the later king Æthelberht II (who ruled until 794) were different people. However, historian D. P. Kirby believes they were the same person. According to Kirby, Beonna might have become king around 758. The fact that he made his own coins could mean that East Anglia became free from Mercian control for a while. This would connect Beonna's rule to the weakening of Mercian power after King Æthelbald died.

Some historians, like Charles Oman, have even suggested that Beornred was the same person as Beonna. Beornred was a king of Mercia for a short time in 757 before Offa took over. Another idea is that Beonna and Beornred might have been relatives from the same royal family. They might have wanted to rule in both Mercia and East Anglia.

In 1996, Marion Archibald and Valerie Fenwick offered a different idea. They used evidence from East Anglian coins and documents written after the Norman Conquest. They thought that Beonna and Beornred were the same person. They suggested that after King Ælfwald died in 749, Æthelbald of Mercia put Beornred/Beonna in charge of northern East Anglia. He put Alberht (who was probably from the Wuffingas family) in charge of the south.

According to Archibald and Fenwick, after Æthelbald was killed in 757, Beornred/Beonna became king of Mercia. During this time, more coins were made in East Anglia, perhaps for military needs. But after only a few months, Offa removed him from power. Beornred/Beonna then had to flee back to East Anglia. Alberht had tried to make East Anglia an independent kingdom and rule alone. He succeeded for a short time. But Beornred/Beonna removed him when he arrived as an exile around 760. Soon after, Offa took control of the East Angles around 760-765 and removed Beonna.

Beonna's Coins

Anglo-Saxon kings started making coins around the 620s. At first, they were made of gold. Then they used electrum (a mix of gold and silver), and finally pure silver. We don't know much about how coins were organized during Beonna's reign. But we can guess that the people who made the coins (called moneyers) worked for the king. The king would have overseen how his coins looked.

In the early 700s, there was a shortage of metal for coins in northern Europe. This probably caused the quality of local coins, called sceattas, to get worse. They had less precious metal in them. Around 740, Eadberht of Northumbria was the first king to fix this problem. He made new coins that were all the same weight and had a lot of silver. These new coins eventually replaced the old, lower-quality ones. Other kings followed his example, including Beonna and the Frankish king Pepin the Short. Pepin seems to have been very influenced by the new coins from Beonna and Eadberht.

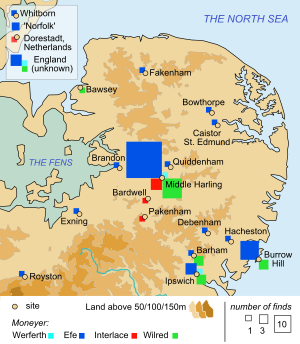

We have found examples of Beonna's coins in two large groups (called hoards). We have also found many individual coins. Before 1968, only five of his coins were known. More coins were found over the next ten years. Then, in 1980, a large group of sceattas and other coins was found at Middle Harling. This place is north-east of Thetford, near the border of Norfolk and Suffolk.

In total, 58 coins were found at Middle Harling. Fourteen were found at Burrow Hill (Suffolk), and 35 from other places in East Anglia and elsewhere. Now, over a hundred of Beonna's coins are known. Most of them are now at the British Museum.

Beonna was the first East Anglian king whose coins showed both his name and his title. His coins are bigger than the older sceattas. But they are still small compared to the pennies made in Anglo-Saxon England several decades later. Overall, Beonna's coins are important because they have runic letters that can be dated. They might show that East Anglia preferred using runic writing.

Beonna had three moneyers whose names we know: Werferth, Efe, and Wilred. The coins made by Werferth are thought to be the oldest. His coins and those made under King Eadberht both had 70% silver. They also looked similar. This suggests we might be able to figure out a timeline for Beonna's coins by using the known timeline for Eadberht's coins. However, Eadberht's rule started in 738, several years before Beonna became king. So, the coins aren't closely related enough to create a perfect timeline.

Efe's coins were made after Werferth's. Efe made the most coins, and their designs changed over time. Where these coins were found suggests that Efe's mint (where coins were made) might have been in northern Suffolk or southern Norfolk. It's possible that the village name Euston, Suffolk, which is south-east of Thetford, comes from Efe.

Efe's coins usually show the king's name and title on the front. They are often spelled with a mix of runes and Latin script. Sometimes parts of the design are not drawn well or are missing. The king's name is usually placed around a central dot (or a cross) inside a circle of dots. This design probably came from Northumbrian coins. The back of the coins had a cross and the letters E F E. These were placed in four sections divided by lines. We know that Efe did not use his coin designs in any special order. Experts have calculated that very few of his coin designs remain undiscovered.

The coins made by Beonna's last known moneyer, Wilred, are very different from Efe's. It's very unlikely they were made at the same place or at the same time. We can also guess that Wilred is the same moneyer who made coins for Offa of Mercia, possibly in Ipswich. Wilred's coins show that Offa had influence over the East Angles earlier than previously thought. But they don't help much in figuring out a clear timeline for Beonna's rule. Wilred's name is always shown in runes. Nearly all the backs of his coins have two crosses placed between the parts of his name (+ wil + red). Most of the fronts show crosses and the king's name in a similar design, but they also include an extra rune. This unique rune, which looks like ᚹ, possibly meant walda ('ruler').

One type of Beonna's coin doesn't name a moneyer. It shows a woven pattern (called an interlace motif) on the back. One of these coins (now lost) was found at Dorestad. Dorestad was an important trading center during Beonna's time. These coins look like coins from the Frankish or Frisian areas, especially those made near Maastricht during that period.

Beonna's rule happened around the same time that Pippin III became king of the Franks after 742. This led to the end of the old Merovingian royal family. It was also around the time Saint Boniface and his followers were killed in Frisia in 754. Two of Beonna's coins use a runic 'a' in the name Beonna. This runic 'a' has only been found elsewhere in Frisia. This suggests that there were trade and language connections between Frisia and East Anglia in the 700s.

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |