History of Portugal facts for kids

The history of Portugal began around 400,000 years ago, when early humans lived in the area that is now Portugal.

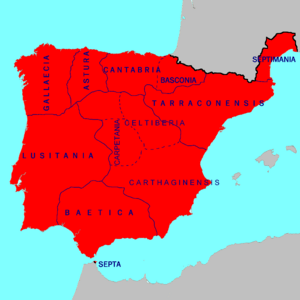

The Romans took almost two centuries to conquer the region. They created provinces like Lusitania in the south and Gallaecia in the north. After the Roman Empire fell, Germanic tribes, like the Suebi and Visigoths, ruled the land from the 5th to the 8th centuries.

In 711, Islamic invaders from the Umayyad Caliphate conquered the Visigoth Kingdom. They established the Islamic state of Al-Andalus across much of Iberia. In 1095, Portugal separated from the Kingdom of Galicia. Afonso Henriques became the first king of Portugal in 1139. The Algarve, Portugal's southernmost region, was taken from the Moors in 1249. In 1255, Lisbon became the capital. Portugal's borders have stayed almost the same since then. King John I led the Portuguese to victory against the Castilians in 1385. He also formed an alliance with England in 1386, known as the Treaty of Windsor.

From the 15th to the 16th centuries, Portugal became a powerful global force during Europe's "Age of Discovery". It built a huge empire. But signs of decline appeared after the Battle of Alcácer Quibir in Morocco in 1578. This defeat led to the death of King Sebastian and many nobles. Portugal then lost its independence for 60 years, joining with Spain from 1580 to 1640. Spain's failed attempt to invade England in 1588 also weakened Portugal, as it had to provide ships. More problems followed, like the destruction of Lisbon in 1755, occupation during the Napoleonic Wars, and losing its biggest colony, Brazil, in 1822. From the mid-1800s to the late 1950s, almost two million Portuguese people moved to Brazil and the United States.

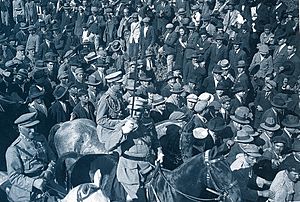

In 1910, a revolution ended the monarchy. A military coup in 1926 started a dictatorship that lasted until another coup in 1974, called the Carnation Revolution. The new government brought in many democratic changes and gave independence to all of Portugal's African colonies in 1975. Portugal is a founding member of NATO, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). It joined the European Economic Community (now the European Union) in 1986.

Contents

- What Does "Portugal" Mean?

- Portugal's Early History

- Roman Rule in Portugal

- Germanic Invasions

- Al-Andalus: Muslim Rule (711–868)

- Reconquista: Taking Back the Land

- Great Discoveries and the Portuguese Empire (15th–16th centuries)

- 1580: Crisis, Spanish Rule, and Decline

- Portuguese Restoration War (1640–1668)

- The Pombaline Era

- Challenges of the 19th Century

- The First Republic (1910–1926)

- Estado Novo: The New State (1933–1974)

- The Third Republic (1974–Present)

- Images for kids

- See also

What Does "Portugal" Mean?

The name Portugal comes from the Latin words Portus Cale. This name changed over time to Portucale in the 7th and 8th centuries, and by the 9th century, it was used for the area between the Douro and Minho rivers. By the 11th and 12th centuries, it became Portugal.

Cale was likely the name of an ancient settlement at the mouth of the Douro River. Around 200 BC, the Romans took Cale from the Carthaginians and renamed it Portus Cale, meaning "Port of Cale." During the Middle Ages, the region around Portus Cale was known as Portucale by the Suebi and Visigoths.

Portugal's Early History

Prehistoric Times

The land we call Portugal has been home to humans for about 400,000 years. Homo heidelbergensis arrived first. The oldest human fossil found here is the 400,000-year-old Aroeira 3 skull. Later, Neanderthals lived in the northern Iberian peninsula. Homo sapiens sapiens (modern humans) came to Portugal around 35,000 years ago and quickly spread out.

Before the Celts, other tribes lived in Portugal. The Cynetes even had a written language, leaving behind many stone markers called stelae.

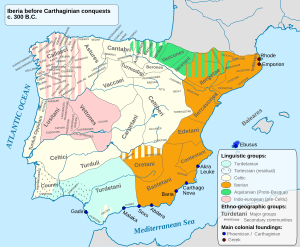

In the first millennium BC, several groups of Celts came from Central Europe. They mixed with the local people to form different tribes. Celts mostly lived in northern and central Portugal. In the south, non-Indo-European cultures remained until the Romans arrived. Small trading posts were also set up by Phoenician-Carthaginians along the southern coast.

Ancient Portugal

Many different tribes lived in Portugal before the Romans invaded in the 3rd century BC. The Roman conquest took several centuries. The Roman provinces covering today's Portugal were Lusitania in the south and Gallaecia in the north.

Many Roman ruins are found across Portugal. Some large city remains include Conímbriga and Miróbriga. You can still see Roman baths, temples, bridges, roads, and homes. Coins, tombs, and pottery are also common finds.

After the Roman Empire fell, the Kingdom of the Suebi and the Visigothic Kingdom ruled the land from the 5th to the 8th centuries.

Roman Rule in Portugal

Roman rule began when the Roman army arrived in the Iberian Peninsula in 218 BC. This was during the Second Punic War against Carthage. The Romans wanted to conquer Lusitania, which included all of modern Portugal south of the Douro river.

Mining was a big reason for Roman interest. They wanted to control the copper, tin, gold, and silver mines. The Romans heavily used mines like Aljustrel and Santo Domingo.

While the south of Portugal was easily taken, the north was harder to conquer. People like the Lusitanians, led by Viriatus, fought back from the Serra da Estrela mountains. Viriatus was a shepherd who used guerrilla tactics and defeated many Roman generals. He was seen as a hero in early Portuguese history. Sadly, he was killed by traitors in 140 BC.

The Romans finished conquering the Iberian Peninsula in 19 BC. In 74 AD, Vespasian gave Latin Rights to most towns in Lusitania. In 212 AD, all free people in the empire became Roman citizens. Later, Emperor Diocletian created the province of Gallaecia in the north, with its capital at Braga. Besides mining, Romans also farmed, growing grapes and grains. They also fished a lot, making a sauce called garum that was sent across the empire. Trade was easier with Roman coins and a network of roads, bridges, and aqueducts.

Roman rule brought people together and helped them move around. Soldiers settled far from home, and mining attracted workers. Romans founded many cities like Olisipo (Lisbon), Bracara Augusta (Braga), and Aeminium (Coimbra). They left a lasting cultural mark. Vulgar Latin, which became the basis of the Portuguese language, became the main language. Christianity also spread throughout Lusitania from the 3rd century.

Germanic Invasions

In 409 AD, as the Roman Empire weakened, Germanic tribes moved into the Iberian Peninsula. In 411, the Suebi and Vandals settled in Gallaecia, forming a Suebi Kingdom with its capital in Braga. The Visigoths were in the south.

The Suebi and Visigoths had the longest impact on Portugal. City life declined during this time. Roman ways mostly disappeared, except for church organizations. The Suebi and Visigoths, who were initially Arian Christians, later became Catholic like the local people.

In 429, the Visigoths moved south and formed a kingdom with its capital in Toledo. Conflicts between the Suebi and Visigoths grew. In 585, the Visigothic King Liuvigild conquered Braga and took over Gallaecia. From then on, the Iberian Peninsula was united under the Visigothic Kingdom.

Under the Visigoths, a new class of nobility became very important. The Church also gained power. Since the Visigoths didn't speak Latin, they relied on Catholic bishops to help run the government. Laws were made by church councils, and clergy became high-ranking.

Al-Andalus: Muslim Rule (711–868)

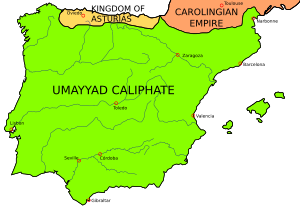

In 711, a Muslim army led by Tariq ibn-Ziyad landed in Gibraltar. They quickly defeated the Visigothic King Roderic and conquered most of the Visigothic kingdom in seven years. The Visigoths had a small ruling class, so their defeat opened the way for the invaders. The local people, who were not happy with the Visigoths, might have welcomed the change.

The Visigothic lands included what is now Spain, Portugal, and parts of France. The Muslim invaders, mostly Berbers from North Africa and some Arabs, called their new lands 'al-Andalus'. In Portugal, they mainly controlled the central and southern regions (old Lusitania). The northern regions (Gallaecia) remained free.

By 714, cities like Évora, Santarém, and Coimbra were conquered. Two years later, Lisbon was under Muslim control. By 718, most of today's Portugal was ruled by the Umayyads. Muslim rule in Iberia lasted until 1492. Many people were allowed to remain Christian, but some regions, including Lisbon, rebelled and became free by the early 10th century.

Reconquista: Taking Back the Land

In 718 AD, a Visigothic noble named Pelagius gathered Christian armies in the northern mountains of Asturias. He planned to use these mountains as a safe place to fight back. After winning the Battle of Covadonga in 722 AD, Pelagius became king of the Christian Kingdom of Asturias. This marked the start of the Reconquista, the war to retake Iberia from the Muslims.

Historians believe that northern Portugal, between the Minho and Douro rivers, kept many of its Christian people. This area was part of the growing Christian kingdoms of Galicia, Asturias, and León.

How Portugal Became a Country

In the late 9th century, a small county was created around Portus Cale by Vímara Peres. This was ordered by King Alfonso III of León. The county grew in size and importance. By the 10th century, its leaders were called "Grand Dukes of the Portuguese." The region became known as Portucale or Portugal. The Kingdom of Asturias later split, and northern Portugal became part of the Kingdom of Galicia and then the Kingdom of León.

In 1070, the Portuguese Count Nuno Mendes wanted the title of King of Portugal. He fought Garcia II of Galicia in 1071, but lost. Garcia then called himself "King of Portugal and Galicia." Later, in 1073, Alfonso VI of Leon took all power and called himself "Emperor of All Hispania." When he died, his daughter Teresa inherited the County of Portugal. In 1095, Portugal officially broke away from the Kingdom of Galicia. Its lands were mostly mountains, moors, and forests, bordered by the Minho River in the north and the Mondego River in the south.

Founding the Kingdom of Portugal

In the late 11th century, a knight named Henry of Burgundy became count of Portugal. He worked to make Portugal independent by combining the County of Portugal and the County of Coimbra. A civil war between León and Castile helped him by distracting his enemies. Henry's son, Afonso Henriques, took control after his father's death.

Portugal's national origin is often traced to June 24, 1128, the date of the Battle of São Mamede. After this battle, Afonso declared himself Prince of Portugal. In 1139, he took the title King of Portugal. In 1143, the Kingdom of León recognized him as king through the Treaty of Zamora. In 1179, Pope Alexander III officially recognized Afonso I as king. The first capital of Portugal was Guimarães, but later, Afonso ruled from Coimbra.

Portugal Becomes Stronger

The Algarve, the southernmost part of Portugal, was finally taken from the Moors in 1249. In 1255, the capital moved to Lisbon. Spain finished its own Reconquista much later, in 1492. Portugal's land borders have stayed almost the same since the 13th century. The border with Spain has barely changed. The Treaty of Windsor (1386) created a strong alliance between Portugal and England that still exists today. From early times, fishing and trade by sea were the main ways Portugal made money.

Great Discoveries and the Portuguese Empire (15th–16th centuries)

In the 15th and 16th centuries, Portugal became a leading European power. It was as influential as England, France, and Spain. Portugal built a huge trading empire across the world, supported by a strong navy.

The Portuguese Empire began on July 25, 1415. The Portuguese navy sailed to Ceuta, a rich Islamic trading city in North Africa. King John I, his sons (including Henry the Navigator), and the hero Nuno Álvares Pereira were part of this fleet. On August 21, 1415, Ceuta was conquered, starting the long-lasting Portuguese Empire.

The conquest of Ceuta was easier because of a civil war among Muslims in North Africa. This war stopped them from taking Ceuta back. Portugal then expanded its empire further.

In 1418, two of Prince Henry the Navigator's captains, João Gonçalves Zarco and Tristão Vaz Teixeira, found an island they called Porto Santo after a storm. In 1419, João Gonçalves Zarco landed on Madeira. The Portuguese settled uninhabited Madeira in 1420.

Between 1427 and 1431, most of the Azores were discovered. These islands were settled by the Portuguese in 1445.

In 1434, Gil Eanes sailed past Cape Bojador, south of Morocco. This was the start of Portugal's exploration of Africa. Before this, Europeans knew very little about what lay beyond the cape, and there were legends of sea monsters. There were some setbacks, like a defeat in Tangier in 1438.

But the Portuguese continued exploring. In 1448, a trading post called a feitoria was built on Arguim island off Mauritania. This allowed gold from Africa to reach Portugal without going through Arab traders. Later, ships explored the Gulf of Guinea, finding uninhabited islands like Cape Verde, São Tomé, and Príncipe.

Prince Henry the Navigator died on November 13, 1460. He had strongly supported sea exploration. After his death, exploration slowed down. But his work showed that new lands could bring profits. So, private merchants took over, pushing trade routes further down the African coast.

In the 1470s, Portuguese ships reached the Gold Coast. In 1471, Portugal captured Tangier. Eleven years later, the fortress of São Jorge da Mina was built in Elmina on the Gold Coast. Christopher Columbus sailed on a fleet bringing building materials to Elmina in 1481. In 1483, Diogo Cão explored the Congo River.

Sea Route to India and the Treaty of Tordesillas

In 1484, Portugal rejected Columbus's idea of sailing west to India, thinking it was too far. Some historians believe the Portuguese had accurate calculations of the world's size. This led to a long argument that ended with the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. This treaty divided the (mostly undiscovered) New World between Portugal and Castile (Spain). Lands to the east of a line 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands belonged to Portugal, and lands to the west belonged to Castile.

With Bartolomeu Dias sailing beyond the Cape of Good Hope in 1487, the riches of India became reachable. The cape was named for the hope of rich trade with the east. Between 1498 and 1501, Pêro de Barcelos and João Fernandes Lavrador explored North America. At the same time, Pêro da Covilhã reached Ethiopia by land. Vasco da Gama sailed to India and arrived at Calicut on May 20, 1498. He returned to Portugal a hero the next year. The Monastery of Jerónimos was built to celebrate the discovery of the route to India.

At the end of the 15th century, Portugal expelled some local Jews and those who had come from Spain. Many Jews were forced to convert to Catholicism. In 1506, 3,000 "New Christians" were killed in Lisbon.

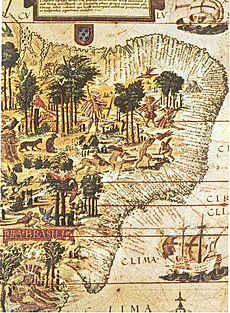

In 1500, Pedro Álvares Cabral sailed from Cape Verde with 13 ships. On April 22, 1500, they saw land. They claimed this new land for Portugal. This was the coast of what became Brazil.

The main goal of the expedition was to open sea trade with the East. Cabral then sailed around the Cape of Good Hope. He reached Sofala on the east coast of Africa in July 1500. A Portuguese fort was built there in 1505, which later became Mozambique.

Cabral's fleet then sailed east to Calicut in India in September 1500. They traded for pepper and opened European sea trade with the East. Ten years later, in 1510, Afonso de Albuquerque conquered Goa on the west coast of India.

João da Nova discovered Ascension Island in 1501 and Saint Helena in 1502. Tristão da Cunha saw the islands named after him in 1506. In 1505, Francisco de Almeida worked to improve Portuguese trade with the Far East. He sailed to East Africa, where several small Islamic states became allies or subjects of Portugal. Almeida then sailed to Cochin and built a fort there.

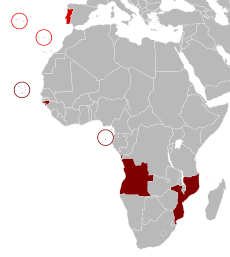

The Portuguese Empire

By the 16th century, Portugal, with only two million people, ruled a huge empire. It had millions of people in the Americas, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. By 1514, the Portuguese had reached China and Japan. In the Indian Ocean, one of Cabral's ships found Madagascar (1501). Mauritius was discovered in 1507. Hormuz in the Persian Gulf was taken by Afonso de Albuquerque in 1515. In 1521, Antonio Correia conquered Bahrain, leading to almost 80 years of Portuguese rule there.

In Asia, the first trading posts were set up by Pedro Álvares Cabral in Cochin and Calicut (1501). More important were the conquests of Goa (1510) and Malacca (1511) by Afonso de Albuquerque. Diu was acquired in 1535. East of Malacca, Albuquerque sent Duarte Fernandes to Siam (Thailand) in 1511. He also sent expeditions to the Moluccas (Spice Islands) in 1512 and 1514. The Portuguese set up their base in the Spice Islands on Ambon. Fernão Pires de Andrade visited Canton in 1517, opening trade with China. In 1557, the Portuguese were allowed to live in Macau. Japan, accidentally reached by three Portuguese traders in 1542, soon attracted many merchants and missionaries. In 1522, one of the ships from Ferdinand Magellan's Spanish expedition completed the first trip around the world.

1580: Crisis, Spanish Rule, and Decline

On August 4, 1578, young King Sebastian died in the Battle of Alcácer Quibir in Morocco. He had no children. His elderly great-uncle, Cardinal Henry, became king. Henry I died just two years later, on January 31, 1580, also without heirs. This led to the Portuguese succession crisis of 1580. Portugal worried about losing its independence and looked for a new king.

One claimant was António, Prior of Crato, a grandson of King Manuel I. He was proclaimed king in some towns but lacked support from the church and most nobles.

Philip II of Spain, also a grandson of Manuel I through his mother, claimed the Portuguese throne. He sent his army, led by the 73-year-old Fernando Alvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba, towards Lisbon.

The Duke of Alba faced little resistance. In August, he was near Lisbon. At the Battle of Alcântara, the Spanish defeated António's army, which was mostly made of peasants and freed slaves. Two days later, the Duke of Alba captured Lisbon. On March 25, 1581, Philip II of Spain was crowned King of Portugal as Philip I. This created an Iberian Union, uniting all of Iberia under the Spanish crown.

Philip rewarded the Duke of Alba with titles like Viceroy of Portugal. The Portuguese and Spanish Empires were now under one ruler. However, resistance to Spanish rule continued in Portugal. António, Prior of Crato, fought on in the Azores until 1583. People even claimed to be King Sebastian, who they hoped would return. This belief, called "Sebastianism," still exists today.

The Portuguese Empire Under Spanish Rule

After the 16th century, Portugal's wealth and influence slowly decreased. Portugal was officially an independent state, but it was joined with the Spanish crown from 1580 to 1640. This meant Portugal lost its own foreign policy. Spain's enemies became Portugal's enemies. England, Portugal's ally since 1386, became an enemy. This led to the loss of Hormuz in 1622. From 1595 to 1663, the Dutch–Portuguese War led to invasions of many Portuguese territories in Asia, Africa, and South America. In 1624, the Dutch took Salvador, the capital of Brazil. In 1630, they took Pernambuco in northern Brazil. A treaty in 1654 returned Pernambuco to Portugal. Both England and the Dutch wanted to control the slave trade and the spice trade.

The Dutch presence in Brazil was a big problem for Portugal. The Dutch captured most of the coast and much of northeastern Brazil. Dutch pirates also attacked Portuguese ships. But a Spanish-Portuguese military operation in 1625 began to turn things around. After the Iberian Union ended in 1640, Portugal regained control over some of its lost territories.

Portuguese Restoration War (1640–1668)

Life was calm under the first two Spanish kings, Philip II and Philip III. They respected Portugal's status, gave jobs to Portuguese nobles, and Portugal kept its own laws, money, and government. There was even a plan to move the Spanish capital to Lisbon. But later, Philip IV tried to make Portugal a Spanish province, and Portuguese nobles lost power.

Because of this, and Spain's financial problems from the Thirty Years' War, the Duke of Braganza, a descendant of King Manuel I, was declared King of Portugal as John IV on December 1, 1640. This started a war for independence against Spain. The governors of Ceuta stayed loyal to Spain.

In the 17th century, many Portuguese people moved to Brazil. From 1709, John V stopped emigration because Portugal had lost too many people. Brazil became a vice-kingdom.

The Pombaline Era

In 1738, Sebastião de Melo, a talented man from Lisbon, began a career as a diplomat. He became the Portuguese Ambassador in London and later in Vienna. Queen Maria Anna of Austria liked him. After his first wife died, she arranged his second marriage to an Austrian noblewoman. King John V of Portugal was not happy and called Melo back to Portugal in 1749. John V died the next year, and his son Joseph I of Portugal became king. Joseph I liked de Melo and made him Minister of Foreign Affairs. As the king trusted de Melo more, he gave him more control of the government.

By 1755, Sebastião de Melo was made prime-minister. He was impressed by Britain's economic success and brought similar ideas to Portugal. He ended slavery in Portugal and its Indian colonies. He also reorganized the army and navy, improved the University of Coimbra, and stopped discrimination against different Christian groups.

But de Melo's biggest changes were in the economy. He created companies and guilds to control trade. He marked out the region for port wine production to ensure its quality, which was the first time this was done in Europe. He ruled strictly, applying laws to everyone from nobles to the poor. He also reformed the tax system. These changes made him enemies among the upper classes, who saw him as a social climber.

Disaster struck on November 1, 1755, when Lisbon was hit by a huge earthquake. The city was destroyed by the earthquake, a tsunami, and fires. De Melo survived and immediately started rebuilding the city. He famously said: "What now? We bury the dead and feed the living."

Despite the disaster, Lisbon's people did not suffer from diseases. The city was rebuilt in less than a year. The new downtown Lisbon was designed to resist future earthquakes. Models were tested by marching troops around them to simulate an earthquake. The buildings and squares of Pombaline Downtown Lisbon are still tourist attractions today. They are the world's first Earthquake-resistant structures. Sebastião de Melo also helped the study of seismology by sending out a survey to every parish in the country.

After the earthquake, Joseph I gave his prime minister even more power. Sebastião de Melo became a powerful, progressive leader. As his power grew, so did his enemies. In 1758, Joseph I was hurt in an assassination attempt. The Távora family and the Duke of Aveiro were accused and executed. The Jesuits were expelled, and their property was taken by the crown. Sebastião de Melo showed no mercy, prosecuting everyone involved. This broke the power of the old nobility. Because of his quick actions, Joseph I made him Count of Oeiras in 1759.

After the Távora affair, the new Count of Oeiras faced no opposition. He was made "Marquis of Pombal" in 1770. He effectively ruled Portugal until Joseph I's death in 1779. However, some historians say that while Pombal brought progress, he also increased his own power, crushed opposition, and censored books.

The new ruler, Queen Maria I of Portugal, disliked the Marquis. She ordered him to stay far away from her, ending his influence.

Portugal's Wars with Spain

In 1707, during the War of the Spanish Succession, a joint Portuguese, Dutch, and British army, led by the Marquis of Minas, conquered Madrid. They declared Archduke Charles of Austria as King Charles III of Spain.

The "Ghost War"

In 1762, France and Spain tried to make Portugal join their alliance against Great Britain. Joseph I refused, saying his alliance with Britain was not a threat.

In spring 1762, Spanish and French troops invaded Portugal. They reached the Douro river, and a second group besieged and captured Almeida. British troops arrived and helped the Portuguese army, led by the Count of Lippe. They stopped the French-Spanish advance and pushed them back. In the Treaty of Paris in 1763, Spain returned Almeida to Portugal.

Challenges of the 19th Century

In 1807, Portugal refused Napoleon Bonaparte's demand to stop trade with the United Kingdom. A French invasion followed, and Lisbon was captured on December 8, 1807. British help in the Peninsular War saved Portugal's independence. The last French troops left in 1812. However, Portugal lost the town of Olivença to Spain.

Rio de Janeiro in Brazil was the Portuguese capital from 1808 to 1821. In 1820, there were revolts in Porto and Lisbon demanding a constitution. Lisbon became the capital again when Brazil declared independence from Portugal in 1822.

King John VI died in 1826, leading to a crisis over who would be king. His oldest son, Pedro I of Brazil, briefly became Pedro IV of Portugal. But neither Portugal nor Brazil wanted a combined monarchy. So, Pedro gave the Portuguese crown to his 7-year-old daughter, Maria da Glória. He said she should marry his brother, Miguel, when she grew up. But some people were unhappy with Pedro's reforms. They wanted Miguel to be king, and he was proclaimed king in February 1828. This led to the Liberal Wars, where Pedro eventually forced Miguel to give up the throne and go into exile in 1834. Maria II then became queen.

After 1815, the Portuguese expanded their trading posts along the African coast, moving inland to control Angola and Mozambique. The slave trade was abolished in 1836. In Portuguese India, trade grew in Goa, and its smaller colonies of Macau (near Hong Kong) and Timor (north of Australia). The Portuguese brought Catholicism and their language to their colonies. Most settlers still went to Brazil.

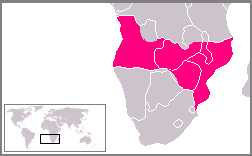

The 1890 British Ultimatum was given to Portugal on January 11, 1890. Britain wanted Portugal to remove its military from the land between Portuguese Mozambique and Portuguese Angola. Portugal had claimed this area on its "Pink Map", but Britain wanted to build a railroad linking its colonies from Cairo to Cape Town. This argument caused protests and led to the fall of the Portuguese government. Many Portuguese saw this as a terrible act by their oldest ally.

The First Republic (1910–1926)

Historians have often focused on the later dictatorship, but the First Republic is now getting more attention. It was a time of big changes. The 5 October 1910 Revolution was led by the Portuguese Republican Party (PRP). Some historians say the PRP turned the republic into a dictatorship. Others see it as a progressive and democratic time.

Religion and the Republic

The First Republic was very anti-church. It wanted to remove the powerful role the Catholic Church had. Historian Stanley Payne said, "Most Republicans believed that Catholicism was the main enemy of individual freedom and had to be completely broken." Under Afonso Costa, the justice minister, the revolution immediately targeted the Church. Churches were robbed, convents attacked, and clergy harassed.

Just five days after the Republic began, the government ordered all convents, monasteries, and religious orders to be closed. Their residents were expelled, and their goods were taken. Jesuits even lost their Portuguese citizenship.

Many anti-Catholic laws followed quickly. On November 3, a law allowing divorce was passed. Laws also recognized children born outside marriage, allowed cremation, made cemeteries secular, stopped religious teaching in schools, and banned priests from wearing their robes in public. Church bells could not ring freely, and public religious festivals were stopped. The government also controlled seminaries, choosing professors and what was taught. All these laws, written by Afonso Costa, led to the Law of Separation of Church and State on April 20, 1911.

The Constitution and Politics

A republican constitution was approved in 1911. It created a parliament with two chambers and limited the president's power. The Republic caused big divisions in Portuguese society, especially among the rural people (who were mostly monarchists), in trade unions, and in the Church. Even the PRP split, with more moderate members forming other parties. Despite this, the PRP, led by Afonso Costa, stayed in power, often using old political tactics. This meant other groups often had to use violence to gain power.

The PRP saw World War I as a chance to achieve several goals: end the threat of a Spanish invasion and foreign control of African colonies, and unite the country behind the new government. However, these goals were not met. Portugal's involvement in the war actually deepened political divisions. This led to two dictatorships, one by General Pimenta de Castro (1915) and another by Sidónio Pais (1917–1918).

Sidónio Pais's rule, known as Sidonismo, was interesting to historians because it had modern ideas. It was like some totalitarian and fascist dictatorships of the 1920s and 1930s. Sidónio Pais tried to bring back traditional values, like the "Homeland." He tried to rule with a strong, personal style.

He tried to get rid of traditional political parties and change how people were represented in parliament. He created a corporative Senate and a single party (the National Republican Party). The state became more involved in the economy, while stopping workers' movements and leftist republicans. Sidónio Pais also tried to restore order and make the republic more acceptable to monarchists and Catholics.

Political Instability

Sidónio Pais was murdered on December 14, 1918, creating a power vacuum. This led to a short civil war. The monarchy was declared restored in northern Portugal on January 19, 1919. Four days later, a monarchist revolt broke out in Lisbon. A republican government, led by José Relvas, fought against the monarchists with loyal army units and armed civilians. The monarchists were finally driven from Porto on February 13, 1919. This victory allowed the PRP to return to power and win the elections that year.

During this time, reforms were attempted to make the government more stable. In August 1919, a conservative president, António José de Almeida, was elected. His office was given the power to dissolve parliament. Relations with the Holy See (the Pope), which Sidónio Pais had restored, were kept. The president used his new power in May 1921 to solve a government crisis, appointing a new government to prepare for elections.

These elections were held on July 10, 1921, and the party in power won, as usual. However, this government did not last long. On October 19, a military coup happened. Several important conservative figures, including Prime Minister António Granjo, were killed. This event, known as the 'night of blood', deeply affected politicians and the public. It showed how weak the Republic's institutions were.

New elections on January 29, 1922, brought a new period of stability. The PRP again won a majority. But unhappiness remained. Many accusations of corruption and the failure to solve social problems weakened the PRP leaders. All political parties, especially the PRP, suffered from internal divisions. The party system was broken and mistrusted.

This is clear because even with regular PRP wins, governments were not stable. Between 1910 and 1926, there were 45 governments. Presidents opposed single-party governments, there was internal disagreement within the PRP, and the party had little discipline. Many different types of governments were tried, but none worked. Force became the only way for the opposition to gain power.

How the Republic Was Seen

Historians often say the republican dream failed by the 1920s. Many people who had supported the Republic in 1910, hoping it would fix the monarchy's problems (unstable government, financial crisis, economic backwardness), concluded that the country needed more than just removing the king. The First Republic failed because of the gap between high hopes and poor results.

However, the First Republic left a lasting impact. It created new civil laws, the basis for an education revolution, the separation of Church and State, and a strong national identity. The national flag, anthem, and street names still define Portugal today. The Republic's main legacy was its memory.

The 1926 Military Coup

By the mid-1920s, conditions favored another authoritarian government. A stronger leader might restore order. Since the opposition could not gain power through elections, they turned to the army. The army's political awareness had grown during the war. Many officers had not forgiven the PRP for sending them to a war they did not want.

To conservatives, the army seemed like the last hope for "order" against the country's "chaos." Conservative figures and military officers formed ties. The 28 May 1926 coup d'état had the support of most army units and political parties. As in 1917, the people of Lisbon did not rise to defend the Republic, leaving it to the army.

Historians still debate the First Republic. Some see it as a progressive and democratic system. Others see it as a continuation of the old, elite governments of the 19th century. A third group highlights its revolutionary and dictatorial nature.

Estado Novo: The New State (1933–1974)

Salazar's Dictatorship

Political chaos, many strikes, bad relations with the Church, and economic problems worsened by a disastrous military role in World War I led to the military 28 May 1926 coup d'état. This coup started the "Second Republic," which began as the Ditadura Nacional (National Dictatorship). In 1933, it became the Estado Novo (New State), led by economist António de Oliveira Salazar. He turned Portugal into a single-party corporate regime. Portugal was neutral in the Spanish Civil War (1936–39), but informally helped the Nationalists.

After the war, Salazar allowed some political liberalization. Opposition parties were tolerated to a degree, but they were also controlled and manipulated. This meant they split into groups and never formed a strong opposition.

World War II

Portugal was officially neutral in World War II. However, Salazar worked with the British, selling them rubber and tungsten. In late 1943, he let the Allies use air bases in the Azores to fight German U-boats. Salazar also helped Spain avoid German control. Portugal also sold tungsten to Germany until June 1944. Salazar worked to regain control of East Timor after the Japanese took it. He also allowed several thousand Jewish refugees into Portugal during the war. Lisbon, with its air links to Britain and the U.S., became a hub for spies and a base for the Red Cross to deliver aid to prisoners of war.

Colonies and Decline

In 1961, the Portuguese army fought against an Indian invasion in its colony of Goa. Portugal lost its colonies in India. Independence movements also became active in Portuguese Angola, Portuguese Mozambique, and Portuguese Guinea. This started the Portuguese Colonial War. About 122,000 Africans died in the conflict. During this time, Portugal was not isolated. It was a founding member of NATO, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA).

After Salazar died in 1970, Marcelo Caetano took over. There was hope that the regime would become more open, a "Marcelist spring." But the colonial wars in Africa continued. Political prisoners remained in jail, freedom of association was not restored, censorship was only slightly eased, and elections were still tightly controlled.

The regime kept its main features: censorship, a corporate system, a market economy controlled by a few groups, and constant surveillance and intimidation by political police. This included arbitrary arrests, political persecution, and even assassinations of those who opposed the regime.

The Third Republic (1974–Present)

The Carnation Revolution on April 25, 1974, was a mostly peaceful military coup. It installed the "Third Republic" and brought in major democratic changes.

The Third Portuguese Republic

The Processo Revolucionário Em Curso (Ongoing Revolutionary Process) was a chaotic time during Portugal's move to democracy. It started after a failed right-wing coup on March 11, 1975, and ended after a failed left-wing coup on November 25, 1975. This period had political unrest, violence, and instability. Industries were nationalized. Portugal was divided between the conservative north, with its many small farmers, and the radical south, where communists helped peasants take over large farms. Finally, in the 1976 election, the Socialist Party won. Its leader, Mário Soares, formed Portugal's first democratically elected government in almost 50 years.

The Social Democratic Party and its center-right allies, led by Prime Minister Aníbal Cavaco Silva, gained control of parliament in 1987 and 1991. The Socialist Party kept the presidency for its popular leader, Mario Soares, in the 1991 presidential election.

Economic and Social Changes

Economic development was a key goal of the Carnation Revolution. Many believed that if the new democracy failed to improve the economy and living standards, it would collapse like earlier democratic governments. Portugal was stagnant compared to Western Europe for much of the Estado Novo period. But the economy started to modernize and grow strongly from 1961 to 1973. Still, the gap between Portugal and Western Europe was huge by the mid-1970s. The Third Republic continued the growth that began in the 1960s. It saw major economic and social development, especially until the early 2000s. GDP per capita rose from 50% of the EC-12 average in 1970 to 70% in 2000. This was a huge step towards Western European living standards. Along with economic growth, the Third Republic also brought big improvements in health, education, infrastructure, housing, and welfare. However, since the early 2000s, the economy has been stagnant.

Portugal's economy declined after the Age of Discoveries. Neither the Constitutional Monarchy nor the First Republic could bring industrialization and development. While António de Oliveira Salazar managed Portugal's finances in the 1930s, the first 30 years of the Estado Novo were marked by stagnation. While the Western world grew strongly after World War II, Portugal lagged behind. By 1960, Portugal's GDP per capita was only 38% of the EC-12 average, making it one of Europe's most underdeveloped countries. However, things changed in the late Estado Novo. From the early 1960s, Portugal saw strong economic growth and modernization. This was due to a more open economy and new leaders. In 1960, Portugal was a founding member of EFTA. This growth allowed Portugal's GDP per capita to reach 56% of the EC-12 average by 1973.

In the early 1970s, the government began to build a welfare state. Reforms were made in health and education. But the new wealth from 1960–73 was not shared equally. The 1960s also saw many people leave Portugal. The April 25, 1974, revolution happened as this growth period was ending due to the 1973 oil crisis. The political turmoil after the coup (especially from March to November 1975) ended this economic growth. Portugal suddenly and chaotically lost its African colonies. From May 1974 to the late 1970s, over a million Portuguese citizens from Africa, called retornados, arrived in Portugal as refugees.

The first 10 years of the Third Republic were tough economically. Portugal received two IMF bailouts. But despite a crisis from 1973 to 1985, there were some years of high growth. Reforms improved living standards, like building a true Social Security system, universal health coverage, and increasing access to education. In 1985, Portugal left the second IMF bailout. In 1986, it joined the European Economic Community (leaving EFTA). Strong economic growth returned. The growth of Portuguese companies and European Union funds led to a new period of strong economic and social development. This lasted until the early 2000s. By 2000, GDP per capita reached 70% of the EU-12 average. However, the economy has been stagnant since the early 2000s. It was hit hard by the Great Recession. Public debt rose sharply, leading to an IMF/EU bailout from 2011 to 2014. Economic growth returned in the mid-2010s.

Here are some examples of Portugal's development in the Third Republic. Portugal's GDP per capita was 54% of Northern and Central European countries in 1975. It rose to 70% in 2000. In 1970, there were 94 doctors per 100,000 people. In 2011, there were 405. In 1970, the infant mortality rate was 55.5 per 1,000 live births. In 2010, it was 2.5, one of the lowest in the world. In 1970, only 37% of births happened in health facilities. By 2000, it was almost 100%. In 1970, only 3.8% of teenagers were in high school. This number rose to 71% in 2010. The illiteracy rate was 26% in 1970 and dropped to 5% in 2010. In housing, in 1970, only 47% of homes had piped water and 68% had electricity. By 1991, 86% had piped water and 98% had electricity.

By 2021, Portugal had the 4th lowest GDP per capita (when comparing purchasing power) in the eurozone.

Images for kids

-

A pedra formosa with Celtic triskelion patterns

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Portugal para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Portugal para niños

- Economic history of Portugal

- History of Portugal (711–1112)

- List of Portuguese Cortes

- List of Portuguese monarchs

- Kings of Portugal family tree

- List of prime ministers of Portugal

- Monuments of Portugal

- Presidents of Portugal

- Timeline of Portuguese history

- Historic villages of Portugal

- Cities:

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |