Spanish invasion of Portugal (1762) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Spanish invasion of Portugal |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Fantastic War | |||||||

William, Count of Schaumburg-Lippe, generalissimus of the Anglo-Portuguese forces that thrice defeated the Spanish and French offensives against Portugal. Painting by Joshua Reynolds. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 8,000 Portuguese 7,104 British (5 infantry regiments, 1 dragoon regiment & 8 artillery companies) |

30,000 Spaniards 94 cannons 10–12,000 French (12 battalions) Total: 42,000 (largest Spanish military mobilisation of the eighteenth century) |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Very low: (14 British soldiers killed in combat, 804 by disease or accidents; Portuguese losses low) |

25-30,000:

|

||||||

The 1762 Spanish invasion of Portugal was a military event that happened between May 5 and November 24, 1762. It was part of a bigger conflict called the Fantastic War. In this war, Spain and France tried to invade Portugal, but they were defeated by the combined forces of Portugal and Great Britain. The people of Portugal also played a big part in resisting the invaders.

At first, only Spanish and Portuguese armies were involved. But soon, France joined Spain, and Great Britain joined Portugal. The war was also shaped by guerrilla warfare, where small groups of fighters used the mountains to attack the enemy. The local people also used a "scorched earth" tactic. This meant they destroyed crops and supplies so the invading armies would have nothing to eat. This made the Spanish and French armies weak, forcing them to retreat with many losses. Most of these losses were from hunger, sickness, and soldiers leaving their armies.

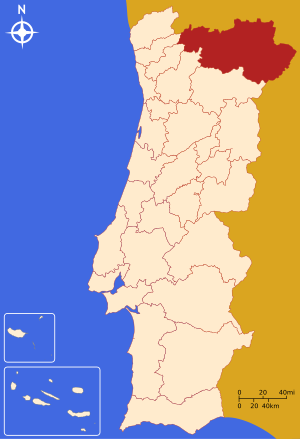

During the first invasion, about 22,000 Spanish soldiers entered northern Portugal. Their main goal was to capture the city of Oporto. They took some forts, but then the Portuguese people rose up against them. The local fighters used the mountains to their advantage. They caused heavy losses for the invaders and cut off their supply lines from Spain. The Spanish soldiers started to starve. They tried to quickly take Oporto but were defeated in battles near the Douro River and Montalegre. After this failure, the Spanish commander, Marquis of Sarria, was replaced by Count of Aranda.

Meanwhile, 7,104 British troops arrived in Lisbon. They helped reorganize the Portuguese army under William, Count of Schaumburg-Lippe. He became the main commander for Portugal and Britain.

In the second invasion, a large army of 42,000 French and Spanish soldiers, led by Aranda, captured Almeida and other strongholds. However, the combined British and Portuguese army stopped another Spanish invasion attempt in the Alentejo province. They also won the Battle of Valencia de Alcántara in Spain, where a third Spanish army was getting ready to invade.

The allied forces managed to stop the invaders in the mountains east of Abrantes. The mountains were steep for the French and Spanish, making it hard for them to move and get supplies. But for the allies, the slopes were gentle, making it easy to move and get supplies. The Anglo-Portuguese army also stopped the invaders from crossing the Tagus River. They defeated them at the Battle of Vila Velha.

The French and Spanish army suffered greatly because their supply lines were cut off by the local fighters. The "scorched earth" tactic was very effective. Villagers left their homes, taking or destroying all food and supplies. The Portuguese government also encouraged enemy soldiers to leave their armies by offering them money. The invaders had to choose between starving or retreating. This led to the French and Spanish army falling apart. They had to retreat to Castelo Branco, closer to the border. A Portuguese force then moved to surround their rear. A report sent to London said that the invaders lost 30,000 men. Most of these were due to starvation, desertion, and capture.

Finally, the allies captured the Spanish headquarters at Castelo Branco. They found many Spanish soldiers who were wounded or sick. These soldiers had been left behind by Aranda when he fled back to Spain.

During the third invasion, the Spanish attacked Marvão and Ouguela. But they were defeated and suffered losses. The allies then left their winter camps and chased the retreating Spanish. They took some prisoners. A Portuguese group even entered Spain and captured more prisoners at La Codosera.

On November 24, Aranda asked for a truce, which was agreed upon and signed on December 1, 1762.

Contents

Why the War Happened

Portugal and Spain Try to Stay Neutral

During the Seven Years' War, Portugal tried to stay neutral. But in 1759, a British fleet defeated a French fleet in Portuguese waters. Portugal's prime minister, Pombal, demanded an apology from Britain. The British government apologized, but the captured French ships were not returned. Spain and France later used this event as an excuse to invade Portugal.

Portugal found it hard to stay neutral. There were small fights between British and French ships in Portuguese harbors. Despite these problems, the Portuguese king, José I, wanted to keep his country out of the war.

Meanwhile, France was pushing Spain to join the war on their side. Spain and France signed a secret agreement called the Family Compact in 1761. This agreement was meant to isolate Britain in Europe. Britain found out about a secret part of the agreement. It said that Spain would declare war on Britain in May 1762. Britain acted first and declared war on Spain in January 1762.

The Franco-Spanish Ultimatum

Spain and France decided to force Portugal to join their Family Compact. The Portuguese king was married to a Spanish princess. In April 1762, Spain and France sent an ultimatum to Lisbon. They demanded that Portugal:

- End its alliance with Britain and form a new one with France and Spain.

- Close its ports to British ships and stop all trade with Britain.

- Declare war on Great Britain.

- Allow a Spanish army to occupy Portuguese ports like Lisbon and Oporto. They said this would "protect" Portugal from Britain.

Portugal was given four days to respond. If they refused, they would face an invasion. Spain and France hoped this would make Britain send troops away from Germany to Portugal. Spain also hoped to take over Portugal and its empire.

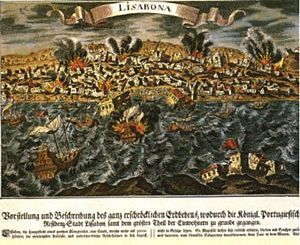

Portugal was in a difficult situation. The great 1755 Lisbon earthquake in 1755 had destroyed Lisbon. Many people died, and most forts were damaged. Rebuilding the city left no money for the army or navy. The gold supply from Brazil, which had made Portugal rich, was also decreasing.

The Portuguese navy was very small. The army was in a terrible state. Soldiers were not paid, and many had no uniforms or weapons. Discipline was very low. When the French ambassador delivered the ultimatum, army sergeants were begging for money. New soldiers were often just homeless people forced into service.

To pressure Portugal, Spanish and French troops started gathering near the Portuguese border in March 1762. They said it was just a "preventive army." Portugal declared that it would fight to the end. When news of the Spanish troops entering the north reached the king, Portugal declared war on Spain and France in May 1762. They asked Britain for money and military help. Spain and France declared war on Portugal in June.

The Invasions Begin

First Invasion: Trás-os-Montes

On April 30, 1762, a Spanish force entered Portugal through the Trás-os-Montes province. They announced that they were coming as "friends and liberators" to free the Portuguese from Britain.

On May 5, the Marquis of Sarria led an army of 22,000 men into Portugal. Portugal officially declared war on Spain and France on May 18, 1762.

The fortress of Miranda was besieged on May 6. A large powder explosion killed 400 people and damaged the walls, forcing the city to surrender on May 9. Other cities like Bragança (May 12) and Chaves (May 21) had no soldiers and were taken without a fight. The Spanish general joked that he couldn't find any Portuguese soldiers.

At first, the invaders seemed friendly with the local people. They paid well for supplies. But Madrid made a mistake: they thought Portugal would surrender easily and entered the country with few supplies. They also thought they could get all the food they needed from Portugal. When this didn't happen, the Spanish army started taking food by force. This caused the local people to rebel.

The "Portuguese Ulcer"

The Spanish thought victory was certain. But suddenly, the people of Trás-os-Montes and Minho provinces started a rebellion. The Spanish faced empty villages with no food or peasants to build roads. Local groups, armed with farm tools and guns, attacked Spanish troops. They used the mountainous terrain to their advantage. The Spanish suffered many losses and sickness. Reports from 1762 said that the Portuguese militia fought back, killing and capturing many Spanish soldiers.

A French source said that over 4,000 Spanish soldiers died in a hospital in Bragança from wounds and disease. Many others were killed by local fighters or starved. The strong Portuguese national feeling and the harsh actions of the Spanish army against villages fueled this revolt. Even the King of Spain complained that Portuguese people were attacking Spanish groups.

The invaders had to split their forces to protect forts, find food, and guard supply convoys. Food had to come from Spain, making it easy for attacks. If the Spanish army couldn't quickly take Oporto, they would starve.

Oporto: A Key Battle

A Spanish force of 3,000 to 6,000 men, led by O'Reilly, marched towards Oporto. This worried the British in the city. But when the Spanish tried to cross the River Douro, they met O’Hara and hundreds of armed peasants. In the battle on May 25, the Spanish attacks were completely defeated. The invaders retreated in a hurry and were chased by the peasants back to Chaves. A French general, Dumouriez, who studied the campaign, said that the peasants, though only 600 strong and without military training, drove the Spanish back with losses.

On May 26, another part of the Spanish army was defeated by Portuguese local forces in the mountains of Montalegre. They also had to retreat.

An army of 8,000 Spanish soldiers sent towards Almeida also lost. They were driven back by militias, suffering 200 casualties. They also lost 600 men in a failed attack on Almeida fortress.

Finally, more troops were sent to Oporto and Trás-os-Montes. They blocked mountain passes, making it hard for the Spanish to retreat. Letters from the British press praised the courage of the militia and the people.

The battle of Douro was very important for the Spanish invasion's failure. Dumouriez explained that if the Spanish had quickly taken Oporto, they would have found supplies and a good climate. This would have changed the whole war.

Spanish Retreat

According to a Spanish historian, over 8,000 Spanish soldiers died during the first invasion. These deaths were caused by local fighters, diseases, and desertion.

The main goal of taking Oporto failed. The Spanish army suffered terrible losses from hunger and local attacks that cut off their food. They were also threatened by the Portuguese regular army. The weakened and discouraged Spanish army had to retreat back to Spain by the end of June 1762. They left behind all their captured areas, except for Chaves. This first invasion was defeated mostly by the local people, with very few regular Portuguese or British troops. Soon after, the Marquis of Sarria was replaced by Count of Aranda.

Spain had lost its chance to defeat Portugal before British troops arrived and joined the Portuguese forces.

Reorganizing the Portuguese Army

Meanwhile, British troops arrived in Lisbon. The first group arrived in May, and the main force arrived in July 1762. In total, 7,104 British officers and soldiers landed. Great Britain also sent supplies, ammunition, and a loan of £200,000 to Portugal.

There were some disagreements between the allies due to language, religion, and jealousy. Portuguese officers felt uncomfortable being led by foreigners. They also earned less than their British counterparts.

Besides feeding the British troops, Lippe faced a big challenge: rebuilding the Portuguese army and combining it with the British army. Lippe chose only 7,000 to 8,000 men out of 40,000 Portuguese soldiers. He sent the rest away as unfit for service.

So, the total allied army was about 15,000 regular soldiers, half Portuguese and half British. Local militias and other groups (about 25,000 men) were used to guard forts. These 15,000 allied soldiers had to face a combined army of 42,000 invaders. This included 30,000 Spanish soldiers led by Count of Aranda and 10,000 to 12,000 French soldiers.

Lippe successfully combined the two armies and led them to victory. A historian noted that Lippe quickly reorganized the Portuguese army. With British help, he drove the Spanish back across the border, even though they had more soldiers.

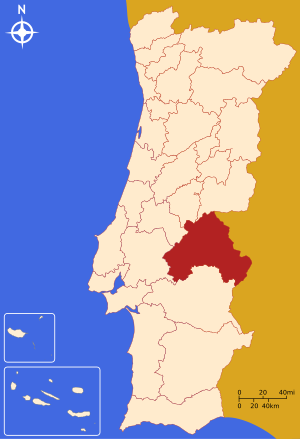

Spanish Invasion Stopped in Alentejo

The French and Spanish army was divided into three groups. The first group invaded northern Portugal (Trás-os-Montes and Minho) in May–June 1762. The second group, reinforced by French troops, invaded central Portugal (Beira) in July–November 1762. The third group was in Spain, near Valencia de Alcántara, ready to invade southern Portugal (Alentejo).

The early successes of the French and Spanish in the second invasion worried King Joseph I. He pressured Count of Lippe for an attack. Since the enemy was gathering troops and supplies near Valencia de Alcántara for a third invasion, Lippe decided to attack them first in Spain. Valencia de Alcántara was a major supply base for the Spanish. The allies had the element of surprise because the Spanish didn't expect such a risky move. They had few guards.

On August 27, 1762, a force of 2,800 British and Portuguese soldiers led by Burgoyne attacked and captured Valencia de Alcántara. They defeated a Spanish regiment, killed soldiers who resisted, and captured flags and officers. Many weapons and ammunition were captured or destroyed.

The Battle of Valencia de Alcántara boosted the Portuguese army's morale. It also stopped a third invasion of Portugal through Alentejo. Alentejo was a flat province where the Spanish cavalry could easily reach Lisbon.

King Joseph I rewarded Burgoyne with a large diamond ring and the captured flags. Burgoyne's reputation grew internationally.

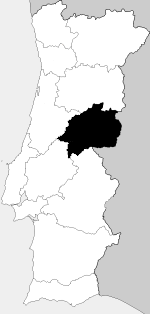

Second Invasion: Beira Province

After being defeated in Trás-os-Montes, Sarria's army returned to Spain and joined the central army. Here, a French army of 12,000 men joined them. This made the total number of invaders 42,000.

False Hope of Victory

The original plan to attack Oporto was dropped. The new plan was to invade Portugal through the Beira province and target Lisbon. Count of Aranda replaced Sarria as commander. The Spanish minister, Esquilache, went to Portugal to help organize supplies for the Spanish army for six months.

Considering how unprepared the Portuguese army was and the huge difference in numbers (30,000 Spanish plus 12,000 French versus 7,000–8,000 Portuguese plus 7,104 British), the Marquis of Pombal prepared ships in Lisbon. These ships were ready to take the Portuguese king and court to Brazil if needed.

At the start of the second invasion, a British observer described the Portuguese soldiers as "wretched." They often went days without food. He worried that Lippe might give up.

Indeed, at first, the French and Spanish army captured several forts with ruined walls and no regular troops. Places like Alfaiates, Castelo Rodrigo, and Almeida surrendered almost without a fight. The allied commander, Lippe, was disappointed. After the war, several fort governors were tried for treason.

Almeida, the main fort in the province, was in such bad shape that a British officer advised its commander to leave the fort and fight from the countryside. The commander refused without orders. The fort's soldiers, about 3,000 to 3,500 men, deserted in large numbers as the enemy approached. Facing 24,000 Spanish and 8,000 French soldiers, and led by an old, incompetent commander, the remaining 1,500 men surrendered after only nine days.

According to Dumouriez, the fort's soldiers fired only a few shots. They were allowed to leave with their weapons and join another Portuguese garrison. The invaders were so surprised by the quick surrender that they agreed to all demands.

The capture of Almeida (with 83 cannons) was celebrated in Madrid as a great victory. This early success made it seem like the French and Spanish were winning. But in reality, taking these forts turned out to be harmful for the invaders. A historian noted that the Spanish forces were worse off after taking these places. They entered wild areas with few roads, food, or water. They lost more men to disease than to fighting.

Also, a new popular revolt made the invaders' situation even worse.

People Fighting Back

The early French and Spanish success in Beira benefited from some local opposition to the Portuguese prime minister, Pombal. But the killings and looting by the invaders, especially the French, soon made the peasants hate them. As the French and Spanish went deeper into Portugal's mountains, they were attacked by local fighters. These fighters cut off their communication and supply lines. A French general noted that the local people, not military strategy, stopped the Spanish and French. He said that a general cannot last long in mountains where armed people cut off supplies.

Several French soldiers who were in the campaign said that the most feared fighters were the local groups from Trás-os-Montes and Beira. The people of Beira even wrote to the Portuguese prime minister saying they didn't need regular soldiers and would fight alone.

Even in the occupied cities, people resisted the French and Spanish. Many were executed.

Abrantes: The Turning Point

Instead of defending the long Portuguese border, Lippe pulled back into the mountains. He defended the line of the Tagus River, which protected Lisbon. Lippe wanted to avoid a big battle against the larger enemy. Instead, he wanted to fight in mountain passes and attack the enemy's sides with small groups. He also wanted to stop the French and Spanish from crossing the Tagus River. If they crossed, they could reach the flat Alentejo province, where their cavalry could easily get to Lisbon.

After capturing Almeida, Aranda marched to cross the Tagus at Vila Velha. But Lippe moved faster. He reached Abrantes and placed troops to block the river crossing. When the invading army arrived, they found all these key positions taken. All boats had been taken or destroyed by the Portuguese.

So, the invaders had two choices: go back to Spain to cross the Tagus (which they thought was dishonorable) or go straight to Lisbon through the mountains north of the capital. Lippe placed some forces in these mountains but left some paths open to encourage the enemy to choose this route. Since Lisbon was the main goal, Aranda advanced. The allied forces strengthened their positions on the heights around Abrantes. These mountains had steep slopes facing the invaders, acting as a barrier. But they were gentle on the allies' side, allowing them to move freely and get reinforcements. The Anglo-Portuguese army stopped the invaders' advance towards Lisbon. This was the turning point of the war.

To break the stalemate, the Spanish attacked towards Abrantes, the allied headquarters. They took the small castle of Vila Velha and forced their way through some mountain passes. But Lippe sent reinforcements, and the allied force defeated the Spanish. On October 5, 1762, the Anglo-Portuguese, led by Lee, attacked and completely defeated the Spanish at Vila Velha. Many Spanish soldiers were killed, and officers were captured. Artillery and supplies were destroyed. On the same day, the Portuguese defeated a French force and captured many valuable supplies.

The invaders could not pass, and their attack failed. The war had turned around. Abrantes proved to be the "key of Portugal" because of its strategic location on the Tagus River.

Scorched Earth Tactics

Both armies stayed at Abrantes, facing each other. But while the Anglo-Portuguese kept getting stronger and receiving supplies, the French and Spanish armies had their supply lines cut off by armed peasants and militias. Even worse, they were starving because of a deadly "scorched earth" tactic. This tactic was used again in 1810–11 against the French.

The Portuguese soldiers and peasants turned the Beira province into a desert. People left their villages, taking all edible food with them. Crops and anything useful to the enemy were burned or taken. Even roads and some houses were destroyed.

So, the tired French and Spanish army had to choose: stay in front of Abrantes and starve, or retreat closer to the border while they still could.

The allied plan worked almost perfectly. It was based on two facts: First, to conquer Portugal, the French and Spanish had to take Lisbon. Second, Lisbon could only be attacked from the mountainous North, which was blocked by the allied defenses at Abrantes. Lisbon was protected by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and the Tagus River to the South and East. This plan used Lisbon's geography and the lack of resources in the Portuguese countryside. It also weakened the French and Spanish army through starvation and attacks on their supply lines by local fighters.

The invading army suffered terrible losses from local fighters, hunger, desertions, and disease. Their situation became impossible. Sooner or later, the French and Spanish army would have to retreat in a very broken state.

Lippe saw that the enemy's situation was desperate. He completed his plan with a bold move. The Portuguese force of General Townshend spread rumors that a large British force of 20,000 new soldiers had landed. This made the discouraged invading army retreat towards Castelo Branco from October 15 onwards. This city was closer to the border and became the new Spanish headquarters.

Then, the allied army left their defensive positions and chased the smaller Spanish army. They attacked its rear, took many prisoners, and recaptured almost all the towns and forts the Spanish had taken. On November 3, 1762, the Portuguese defeated a retreating Spanish cavalry force. The British also swept another Spanish group from Salvaterra. The Spanish, who had entered Portugal as conquerors, were now being chased in a devastated enemy land. The war had changed: the hunter had become the hunted.

French and Spanish Army Collapses

During the retreat, the French and Spanish army, weakened by hunger, disease, and heavy rains, fell apart. Thousands of soldiers left their armies. The Portuguese government offered money for each Spanish soldier who deserted. Those who joined the Portuguese army got even more. Stragglers and wounded soldiers were killed by peasants.

Letters from the time describe the Spanish army as being in a "ruinous shattered condition." Lippe wrote that the army was "decimated by starvation, desertion and disease." The British ambassador in Portugal reported that the French and Spanish army lost about 30,000 men during the first two invasions. This was almost three-quarters of their original army. Other sources confirm these high losses.

French historian Isabelle Henry wrote that the Spanish lost 25,000 men. American historian Edmund O'Callaghan estimated that the Spanish army lost half its men before retreating.

Dumouriez, who visited Portugal and Spain to study the campaign, reported that the Spanish lost 15,000 men in the second invasion and 10,000 in the first. He noted that the campaign "covered Spain with dishonour."

The tactics used in 1762 were similar to those used against Napoleon in Portugal in 1810–1811. In both cases, the invaders were stopped by a "scorched earth" policy and attacks by local fighters.

The British losses were very low: 14 soldiers killed in combat and 804 died from other causes, mostly disease. The key to victory was destroying the enemy without fighting big battles. Instead, the allies attacked when the enemy retreated.

Spanish Headquarters Falls

The Anglo-Portuguese victory was clear when they captured the Spanish headquarters in Castelo Branco. When the allied army began to surround the Spanish forces in Castelo Branco, they fled to Spain. They left behind all their wounded and sick soldiers. Aranda sent a letter to the Portuguese commander, Townshend, asking for humane treatment for his captured men.

The number of Spanish sick men in hospitals was estimated at 12,000. The Spanish army in Castelo Branco was suffering from a terrible epidemic. This epidemic even spread to the Portuguese people when they returned to the city. So, the joy of victory was mixed with sadness for the many sick and dead.

Spain's defeat in Portugal was made worse by losses in its empire and at sea. In one year, Spain's armies were beaten in Portugal, and they lost Cuba and Manila. Their trade was destroyed, and their fleets were wiped out.

Lippe Rewarded

Except for two border forts, all the occupied territory was freed. The remaining invading armies were driven out and chased to the border, and even into Spain. For example, at Codicera, several Spanish soldiers were captured. Portugal had refused to join France and Spain, and Britain sent help. The invaders were driven back and chased into Spain.

After the war, Lippe was asked by the Portuguese prime minister, Pombal, to stay in Portugal to reorganize the army. He agreed. When Lippe returned to his own country, he was praised by many, including the famous writer Voltaire. The King of Portugal gave him many gifts, including six gold cannons, as a sign of thanks for saving his throne. The King also said that Lippe would remain the nominal commander of the Portuguese army, even when absent. He was also given the title of "Serene Highness."

The British government also rewarded him with the title of "honorary Field Marshal."

Third Invasion: Alentejo

The third invasion was influenced by peace talks between France and Great Britain. Spain wanted to capture some Portuguese territory to use as a bargaining chip in the peace negotiations. These talks led to the Treaty of Paris in February 1763.

Surprise Attack

The remaining French and Spanish troops were in winter camps in Spain. The allied army was also in winter camps in Portugal. By this time, the French army was almost out of action due to many dead, deserters, and sick soldiers.

However, Aranda thought he could surprise the Portuguese garrisons if he attacked before spring. This time, the flat land in the Alentejo province would help the Spanish cavalry.

He knew that Portuguese forts were only manned by less experienced troops. Also, the poor state of the Portuguese forts in Alentejo seemed like an invitation to invade. A British general even suggested removing some large guns from the forts to prevent them from being captured.

But Lippe had taken steps to prepare. He strengthened the garrisons of the Alentejo forts near the border. He also moved some regiments to the south of the Tagus River in Alentejo. He created a reserve force with British and Portuguese troops. Some British officers were sent to command Portuguese garrisons in key forts. These preparations proved very important.

The Attack

For this campaign, the Spanish gathered three large groups near Valencia de Alcántara. This time, they split their army into several parts, with each attacking a different target.

A Spanish force of 4,000 or 5,000 men tried to take Marvão with a direct attack. The scared people wanted to surrender, but Captain Brown stood firm and ordered his men to fire. The Spanish were defeated with many losses and fled.

Another Spanish force attacked Ouguela on November 12, 1762. Its walls were ruined, and it had only a small group of irregular fighters and 50 riflemen. But they defeated the enemy, who fled, leaving many dead. The King of Portugal promoted Captain Brás de Carvalho and the other officers. The attack on Campo Maior also failed because one Spanish unit did not support another.

Third Retreat, Second Chase

Eventually, Lippe mobilized the entire allied army on November 12, 1762. He moved all units south of the Tagus River as soon as he heard about the enemy's attack.

The Spanish were discouraged by these failures. In the two previous invasions, they had taken forts easily. This time, not a single fort was captured, giving the Portuguese time to gather troops. The Portuguese army was now well-trained and led. Its reputation and numbers grew with volunteers. In contrast, the French and Spanish army was much smaller after its losses.

Once again, the Spanish army was forced to retreat on November 15, 1762. And for the second time, it was chased by Anglo-Portuguese groups, who took many prisoners. A few more prisoners were even taken inside Spain when the Portuguese garrison made a successful raid on La Codosera on November 19.

Spain Seeks a Truce

On November 22, 1762, seven days after the Spanish retreat from Portugal began, the commander of the French and Spanish army, Count of Aranda, sent a peace proposal to the Anglo-Portuguese headquarters. He asked for a suspension of fighting. It was accepted and signed nine days later, on December 1, 1762.

However, Aranda tried one last move to save face. On the same day he asked for a truce, he sent 4,000 men to capture the Portuguese town of Olivença. But the Spanish retreated when they found out the garrison had just been reinforced. Lippe told Aranda that this behavior was strange for someone who wanted peace.

A preliminary peace treaty had been signed, but the final treaty was signed on February 10, 1763. By this treaty, Spain had to return the cities of Almeida and Chaves to Portugal. They also had to return Colonia del Sacramento in South America. Spain also made big concessions to the British, giving up Florida and other rights.

Meanwhile, Portugal also captured Spanish territories in South America in 1763. The Portuguese won most of the Rio Negro valley in the Amazon. They also successfully defended their territory in Mato Grosso from a Spanish army.

So, the conflict between Portugal and Spain in South America during the Seven Years' War ended in a draw. However, Spain lost almost all the territory it had conquered, while Portugal kept its gains.

Why Spain Failed

Spanish Prime Minister Manuel Godoy, Prince of the Peace later said that the French and Spanish defeat in 1762 was mainly due to the peasant uprising. This was caused by the invaders' harsh actions. He said that 40,000 Spanish and 12,000 French soldiers only managed to take Almeida and go a few miles inland. Then they were defeated in the mountains with little honor.

This war, called the Fantastic War in Portugal, had no big formal battles. It was a war of movements and strategy. The French and Spanish armies failed to reach their goals and had to retreat with huge losses.

The mountainous land and the breakdown of supply lines were key factors. The allies used the terrain well and caused the supply lines to collapse.

Ultimately, the skill of Count Lippe and the discipline of British troops helped reorganize the Portuguese army quickly. This led to a Portuguese victory that many thought was impossible.

Most important was the hatred and resistance of the local people to the foreign invaders. The French and Spanish army faced a revolt from the people, similar to Spain's fight against Napoleon in 1808. This resistance was helped by British troops.

The Spanish also made several mistakes. They changed their plans three times, and they replaced their army commander at a critical moment. Their relationship with the French was also poor. The Spanish commander even complained about the cruel actions of French troops against Portuguese villages. Also, a large Spanish fleet sent to America took resources away from the army invading Portugal. This also stopped Spain from attacking Portugal by sea.

The large number of French and Spanish soldiers was misleading. They had to split their forces to hold forts, find food, chase local fighters, guard supplies, and build roads. The remaining troops for main operations were few, starving, and discouraged.

Spain's Loss of Prestige

Many people at the time believed that the huge losses suffered by the Spanish in Portugal damaged Spain's reputation.

- A French general in 1766 said: "The independence of Portugal cost Spain its glory, its treasure, and an army."

- An anonymous Spanish writer in 1772 said that the "discrediting and destruction of a splendid army" in Portugal made Europe think Spain's power was more imagined than real.

- A Spanish satire joked about Spain losing an army in Portugal and a navy in Cuba in just six months.

- A Spanish scholar who studied the defeat in 1772 said that the war caused the loss of many troops and civilians. He noted that in Galicia alone, over 60,000 people were lost because of the war.

- The French Foreign Minister blamed the Spanish for their "unbelievable campaign" in Portugal.

Spain's involvement in the war did not save France from defeat. Instead, it made things worse for Spain. However, after the war, Spain focused on peace and began a successful period of reforms and modernization.

Trials in Spain

After the Seven Years' War, Spain held a military court to judge the leaders involved in the fall of Havana to the British. The Count of Aranda, who lost in Portugal, was the president of this court. The punishments were very harsh. Aranda even asked for the death penalty for a former Viceroy of Peru, who was just caught in the Havana siege by chance.

The devastating defeat caused a lot of anger in Spain, and people demanded someone be blamed. But it was ironic that the commander who lost in Portugal judged the commander who lost Cuba. A Spanish historian noted that this trial helped hide the true failure of the war from the public.

Stalemate in South America

The Spanish invasion of Portugal in Europe also led to more border fights between the Portuguese colony of Brazil and Spanish territories. These fights had mixed results.

- River Plate: A Spanish expedition captured the Portuguese port of Colónia do Sacramento. They also captured 27 British merchant ships. When a small Portuguese fleet tried to retake Colonia do Sacramento, it was defeated. The Spanish also captured the forts of Santa Teresa and San Miguel.

- Rio Grande do Sul (South Brazil): The Spanish advanced and conquered most of the large and rich territory of Rio Grande do Sul. The Portuguese had only a few soldiers there.

However, the Portuguese defeated the Spanish at the Battle of Santa Bárbara. They captured cannons, cattle, and horses. This large territory would later be retaken by the Portuguese.

- Rio Negro (Amazonia, North Brazil): Portugal conquered the Rio Negro valley in 1763. They built two forts there using Spanish cannons.

- Mato Grosso (western Brazil): The Portuguese successfully defended their territory in Mato Grosso from a Spanish army. The Spanish army suffered from disease, starvation, and desertions and had to retreat. The Portuguese kept the disputed territory and all its artillery.

So, the conflict between Portugal and Spain in South America during the Seven Years' War ended in a tactical draw. But it was a strategic victory for Portugal in the short term. Spain lost almost all the territory it had conquered, while Portugal kept its gains.

Images for kids

-

The 1755 Lisbon earthquake caused great destruction.

-

The city of Oporto.

-

John Campbell, 4th Earl of Loudoun, second in command of the Anglo-Portuguese army.

-

Brigadier-General John Burgoyne.

-

The Duke of Wellington.

-

General Charles-François Dumouriez.

-

Portrait of Count of Aranda.

-

Burgoyne's 16th Light Dragoon (British).

-

Portrait of Voltaire.

See also

In Spanish: Invasión española de Portugal de 1762 para niños

In Spanish: Invasión española de Portugal de 1762 para niños