Factory (trading post) facts for kids

A factory was a special kind of trading center used a long time ago, during the Middle Ages and Early modern period. It was like an early version of a free-trade zone or a place where goods were moved from one ship or vehicle to another.

At a factory, people from the local area could meet and trade with merchants from other countries. These foreign merchants were often called "factors." Factories first started in Europe and then spread to many other parts of the world.

European countries also set up factories in Africa, Asia, and the Americas starting in the 1400s. These factories often became official parts of those European countries, like early steps towards colonialism.

A factory could be many things at once: a market, a warehouse for storing goods, a customs office, a defense point, and a place to help with navigation and exploration. Sometimes, it even acted as the main office or government for local communities.

In North America, Europeans started trading with Native Americans in the 1500s. They built factories, also called trading posts, in Native American lands where they could trade things like furs.

Contents

What Were European Medieval Factories?

Even though European colonialism has roots in ancient times, "factories" were a special idea that started in medieval Europe.

At first, factories were groups of European merchants from the same country who met in a foreign place. These groups worked together to protect their shared interests, especially their money and trade. They also helped with things like insurance and safety. This allowed them to keep up good relationships and trade with the foreign country where they were located.

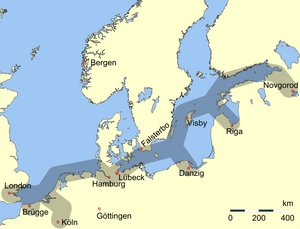

Factories were set up from 1356 onwards in major trading cities, usually ports. Many of these cities grew thanks to the Hanseatic League, a powerful group of trading cities, and its guilds and kontors (their own trading offices). Hanseatic cities had their own laws and provided their own protection. The Hanseatic League had factories in places like Boston and King's Lynn in England, Tønsberg in Norway, and Åbo in Finland. Later, cities like Bruges and Antwerp tried to take over trade from the Hanseatic League by inviting foreign merchants to join them.

Because foreigners usually couldn't buy land in these cities, merchants would gather around factories. For example, the Portuguese had a factory in Bruges. The "factor" (the main merchant) and his helpers would rent homes and warehouses. They would also help settle trade disagreements and even manage insurance money. They acted like both a business group and an embassy, sometimes even settling arguments among the merchants themselves.

Portuguese Feitorias (Around 1445)

During the Age of Discovery, when Portugal was expanding its lands and trade, they adapted the idea of the factory. They called their factories feitorias (pronounced fay-toh-REE-ahs). These spread from West Africa all the way to Southeast Asia.

Portuguese feitorias were usually fortified trading posts built along coastlines. Their main purpose was to bring all the local trade to one place, so Portugal could control it. They served as a market, a warehouse, a place to help ships, and a customs office all at once. A "feitor" (factor) was in charge. This person managed the trade, bought and sold goods for the king, and collected taxes, usually 20%.

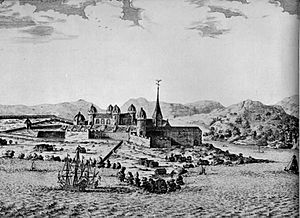

The first Portuguese feitoria overseas was built by Prince Henry the Navigator in 1445 on Arguin island, off the coast of Mauritania. It was meant to attract Muslim traders and control the trade routes in North Africa. It became a model for many other African feitorias, with Elmina Castle being one of the most famous.

Between the 1400s and 1500s, Portugal built about 50 forts that either contained or protected feitorias. These were located along the coasts of West and East Africa, the Indian Ocean, China, Japan, and South America. Important Portuguese factories in the Portuguese East Indies included Goa, Malacca, Ormuz, Ternate, and Macao. The rich possession of Bassein later became Bombay (Mumbai), a major financial center in India.

These factories mainly traded gold and slaves on the coast of Guinea, spices in the Indian Ocean, and sugar cane in the New World. They also helped with local triangular trade between different places, like Goa, Macau, and Nagasaki. They traded goods such as sugar, pepper, coconuts, timber, horses, grain, exotic bird feathers, precious stones, silks, and porcelain from the East. In the Indian Ocean, trade at Portuguese factories was boosted by a system of ship licenses called cartazes.

From the feitorias, products went to the main hub in Goa, then to Portugal. There, they were managed by the Casa da Índia (House of India), which also handled exports to India. The goods were sold in Portugal or sent to the Royal Portuguese Factory in Antwerp to be distributed across Europe.

These factories were easy to supply and defend by sea, acting like independent colonial bases. They kept the Portuguese safe and sometimes even protected the local areas where they were built from fights and piracy. They allowed Portugal to control trade in the Atlantic and Indian oceans, helping them build a large empire even with limited people and land. Over time, some feitorias were given to private business owners, which sometimes caused problems between these private interests and local people, like in the Maldives.

Dutch and Other European Factories (1600s)

Other European powers began setting up their own factories in the 1600s. The Dutch were first, followed by the English. They took over some Portuguese feitorias and built new ones as they explored the coasts of Africa, Arabia, India, and Southeast Asia, searching for the valuable spice trade.

Factories were then created by large trading companies like the Dutch East India Company (VOC), started in 1602, and the Dutch West India Company (WIC), started in 1621. These factories allowed European companies to trade with local people and with their colonies. Many colonies actually started as a factory with warehouses. These factories often had very large warehouses to hold the many products from the growing farms in the colonies, especially in the New World, where farming was boosted by the Atlantic slave trade.

At these factories, products were checked, weighed, and packed carefully for the long sea journey. Spices, cocoa, tea, tobacco, coffee, sugar, porcelain, and fur were especially protected from salty sea air and spoilage. The "factor" was the company's representative for all trade matters. They reported to the main office and were responsible for storing and shipping the products correctly. Since it took a long time for information to travel, the company had to trust the factor completely.

Some Dutch factories were in Cape Town (South Africa), Mocha (Yemen), Calicut and the Coromandel Coast (southern India), Colombo (Sri Lanka), Ambon (Indonesia), Fort Zeelandia (Taiwan), Canton (southern China), Dejima Island (Japan – the only legal trading point with the outside world during the Edo Period), and Fort Orange in what is now Upstate New York in the United States.

North American Factories (1697 to 1822)

American factories often played a strategic role, sometimes acting as forts. They offered some protection for colonists and their allies from hostile Native American groups and other foreign colonists.

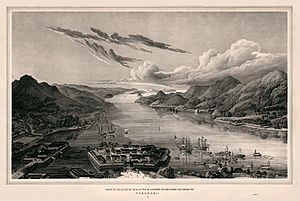

York Factory was founded by the Hudson's Bay Company in 1697. For a long time, it was the company's main office and acted as the government in parts of North America, like Rupert's Land, before European colonies were fully established there. It controlled the fur trade across much of British-controlled North America for centuries and helped with early explorations. Its traders and trappers built early relationships with many Native American groups. A network of these trading posts became the starting point for later official governments in many areas of Western Canada and the United States.

The early coastal factory model was different from the French system. The French set up many trading posts inland and sent traders to live among the local tribes. When war broke out between France and England in the 1680s, both sides regularly attacked and captured each other's fur trading posts. In 1697, Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville, a French commander, used a trick to capture York Factory after defeating three British ships. York Factory changed hands several times over the next decade. It was finally given permanently to Britain in the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht. After the treaty, the Hudson's Bay Company rebuilt York Factory as a brick star fort at the mouth of the nearby Hayes River, where it stands today.

The United States government also had its own factory system from 1796 to 1822. These factories were spread throughout the country's territories.

These factories were officially meant to protect Native Americans from being cheated, through laws called the Indian Intercourse Acts. However, in reality, many tribes gave up large amounts of land in exchange for these trading posts. This happened, for example, in the Treaty of Fort Clark, where the Osage Nation gave up most of Missouri at Fort Clark.

A blacksmith usually worked at the factory to fix tools and build or maintain plows. Factories often also had some kind of milling operation to process grains.

These factories showed the United States' effort to continue a system first started by the French and then the Spanish. This system officially controlled the fur trade in Upper Louisiana.

Factories were often called "forts" and had many unofficial names. Laws were often passed to have soldiers at these "forts," but their real purpose was usually as a trading post.

Examples of North American Factories

- York Factory was founded by the Hudson's Bay Company in 1697.

- Some U.S. government factories included:

- For the Creek people: Colerain (1795–1797) and Fort Hawkins (1809–1816).

- For the Cherokee people: Fort Tellico (1795–1807).

- For the Choctaw people: Fort St. Stephens (1802–1815).

- Other notable factories: Fort Detroit (1802–1805), Fort Chicago (1805–1822), Fort Madison, Iowa (1808–1815), and Fort Osage (1808–1822).

See also

In Spanish: Factoría para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |