Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula facts for kids

The Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula was when the Roman Republic took control of lands in the Iberian Peninsula. These lands were once held by native tribes like the Celts, Iberians, Celtiberians, and Aquitanians, as well as the Carthaginian Empire. The Romans took over Carthaginian areas in the south and east of the peninsula in 206 BC during the Second Punic War. Over time, Rome slowly expanded its control over most of the Iberian Peninsula. This process finished after the Roman Republic ended in 27 BC. Augustus, the first Roman emperor, made the entire peninsula part of the Roman Empire in 19 BC.

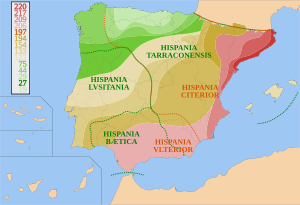

The conquest started after Rome defeated the Carthaginians in 206 BC during the Second Punic War (218–201 BC). Carthaginian forces then left the peninsula. This meant Rome had a lasting presence in southern and eastern Hispania. Four years after the war, in 197 BC, the Romans set up two provinces. These were Hispania Citerior (Nearer Spain) along most of the east coast, and Hispania Ulterior (Further Spain) in the south.

For the next 170 years, the Roman Republic slowly grew its power in Hispania. This happened through trade, diplomacy, and Roman culture spreading. Sometimes, the Romans used military force when local tribes resisted. They turned some native cities into places that paid taxes to Rome. They also built Roman settlements to expand their control. Roman governors in Hispania often acted quite independently because Rome was so far away. Later, the Roman Senate tried to control these governors more, especially to stop them from being unfair or taking too much from the locals. During this time, many local tribes slowly adopted Roman culture, economy, and laws.

Things changed when emperors began to rule Rome. After the Romans won the Cantabrian Wars in the north of the peninsula, which was the last big rebellion, Emperor Augustus conquered northern Hispania. He then officially made the whole peninsula part of the Roman Empire and reorganized its administration in 19 BC.

The Roman province of Hispania Citerior became much larger, including eastern central and northern Hispania. It was renamed Hispania Tarraconensis. Hispania Ulterior was split into two new provinces: Baetica (most of modern Andalusia) and Lusitania. Lusitania covered present-day Portugal up to the River Durius (Douro), plus parts of modern Spain.

Contents

The Second Punic War in Hispania

Carthage's Start in Iberia

From the 8th to 7th centuries BC, the Phoenicians and later the Carthaginians set up trading posts in southern and eastern parts of the Iberian Peninsula. They exported minerals and other resources from Iberia and brought in goods from the Eastern Mediterranean.

Later, Greek traders also came to the coast. They founded trading cities like Emporion (Ampurias). Because of contact with Greeks and Phoenicians, some local peoples on the coast started to adopt parts of these Eastern Mediterranean cultures.

After Rome defeated Carthage in the First Punic War (264–241 BC), Carthage lost important islands like Sicily. To make up for this, Hamilcar Barca conquered southern Spain. His family built a Carthaginian empire in most of southern Hispania. They controlled local tribes by force, by collecting taxes, or by making alliances and marriages with local leaders. Hispania became a key source of soldiers and mercenaries for Carthage, especially the famous Balearic slingers and Celtiberians.

The Ebro River Agreement

In 226 BC, Hasdrubal the Fair, Hamilcar's son-in-law, made a treaty with Rome. It said that neither side should expand their control beyond the River Ebro. The city of Saguntum (Sagunto), located between the two empires, was to remain independent. Cities north of the Ebro were worried about Carthage growing stronger, so they allied with Rome for protection. Saguntum also allied with Rome, even though it was south of the Ebro and close to New Carthage (modern Cartagena), a city founded by Hasdrubal. Later, Hannibal, Hamilcar's son, expanded Carthaginian lands northwards, surrounding Saguntum.

The Problem with Saguntum

The Second Punic War between Carthage and Rome began because Hannibal attacked Saguntum. Hannibal found an excuse to fight Saguntum due to a dispute between the city and a nearby tribe. Saguntum asked Rome for help. The Roman Senate sent officials to warn Hannibal, but he had already started besieging Saguntum.

Saguntum's strong walls and brave people resisted Hannibal's attack for a long time. Hannibal himself was seriously wounded. Roman officials tried to reach him, but he refused to see them. He also sent a letter to Carthage, telling his supporters to prevent any peace deals with Rome. The Carthaginian council sided with Hannibal, saying Saguntum had started the war.

After eight months, Hannibal finally captured Saguntum. The people threw their gold and silver into a fire rather than let Hannibal have it. Hannibal seized the city and many people were killed. Hannibal then spent the winter in Cartago Nova.

Rome felt ashamed for not helping Saguntum and was unprepared for war. They expected Hannibal to cross the Ebro and feared he might encourage tribes in northern Italy to rebel. Rome decided to fight two campaigns: one in Africa (Carthage's homeland) and one in Hispania. They raised a large army and fleet. Publius Cornelius Scipio was assigned to lead the expedition to Hispania. Rome sent a final group to Carthage to declare war if Carthage supported Hannibal's actions. Carthage accepted the war.

Roman Campaigns in Hispania

Early Battles

In 218 BC, the Roman army for Hispania landed at Massalia (Marseilles), only to find Hannibal was already on his way to Italy. Publius Cornelius Scipio sent his brother, Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Calvus, to Hispania with most of the army. Gnaeus landed at Emporion (Empúries). He gained support from local tribes north of the Ebro. Hanno, the Carthaginian commander in Hispania, was defeated by Gnaeus in the Battle of Cissa near Tarraco (Tarragona). Hanno lost 6,000 men and was captured.

Hasdrubal, another Carthaginian commander, then attacked the Roman fleet near Tarraco. He caused some damage but withdrew before Gnaeus Scipio returned. Hasdrubal then encouraged the Ilergetes tribe to revolt. Gnaeus Scipio quickly put down this rebellion and forced them to give hostages and money. He also defeated other Carthaginian allies.

In 217 BC, Hasdrubal marched his army along the coast with his ships nearby. Gnaeus Scipio attacked the Carthaginian fleet at the mouth of the Ebro River. In the Battle of Ebro River, the Roman ships won easily, capturing 25 Carthaginian ships. Hasdrubal retreated. The Romans then raided coastal lands. Meanwhile, Celtiberian tribes attacked near Cartago Nova, defeating Hasdrubal and taking many prisoners.

Publius Scipio joined his brother with reinforcements. They marched to Saguntum. In 216 BC, Hasdrubal received more troops from Africa. He faced revolts from local tribes who were unhappy with Carthage. Hasdrubal put down these revolts. Carthage then ordered Hasdrubal to go to Italy to help Hannibal. The Scipio brothers tried to stop him. They attacked Carthaginian allies, forcing Hasdrubal to stay in Hispania.

In 215 BC, Mago Barca, Hannibal's brother, was preparing to go to Italy. But Carthage sent him to Hispania instead. The Romans won a major battle against three Carthaginian armies near Iliturgi, capturing their camps. Livy wrote that "nearly all the tribes of Spain went over to Rome."

In 214 BC, the Carthaginians, with three commanders, attacked the Romans. However, the Romans won several battles, inflicting heavy losses. They then recaptured Saguntum and destroyed the city of the Turduli, who had started the war with Saguntum.

In 213 BC, the Scipios made an alliance with Syphax, a king in western Numidia (Algeria), who was rebelling against Carthage. The Romans also hired Celtiberian mercenaries for the first time.

The Scipios' Defeat

In 212 BC, the two Scipio brothers decided to end the war. They hired 20,000 Celtiberians. They split their forces to attack the Carthaginian armies. However, Hasdrubal Barca bribed the Celtiberians to leave Gnaeus Scipio's army. Meanwhile, Publius Scipio faced constant attacks from Masinissa and his Numidian cavalry. Publius Scipio was killed in battle.

Gnaeus Scipio realized his brother was defeated and tried to retreat. He was pursued by Numidian cavalry and then by the Carthaginian armies. He led his men to a rocky hill, but it was not a good defensive position. The Romans were slaughtered, and Gnaeus Scipio was killed 29 days after his brother.

The Roman defeat was almost complete. However, a Roman officer named Lucius Marcius rallied the remaining forces. He strengthened their camp and surprised the Carthaginians with an attack. He also launched a successful night attack on two Carthaginian camps, causing heavy losses.

Scipio Africanus Takes Command

In 211 BC, the Roman Senate sent Gaius Nero to Hispania with new troops. He took command of the remaining Roman forces. He trapped Hasdrubal (Hamilcar's son) in a mountain pass. Hasdrubal tricked Nero into talks, allowing his army to sneak out.

The Roman Senate decided to send a new commander-in-chief and more troops. Publius Cornelius Scipio, the son and nephew of the two Scipios who died, was elected. He was only 24 years old and had not held high office before. Scipio arrived in Hispania and quickly gained the trust of friendly tribes.

In 210 BC, Scipio marched on Cartago Nova (Cartagena), a major Carthaginian stronghold. It held their war supplies, money, and hostages. Scipio planned a surprise attack. He attacked the city from the land side, while his fleet attacked from the harbor. The initial land attack failed. However, Scipio learned from local fishermen that the lagoon protecting one side of the city became very shallow at low tide. He led 500 men through the shallow water, climbed the undefended wall, and entered the city. The defenders were caught by surprise, and the city fell.

This victory was very important. It moved the war into enemy territory. Scipio captured the Carthaginian arsenal and treasure. He released the citizens of Cartago Nova and returned their property. He recruited non-citizens and slaves as oarsmen and craftsmen. He also released the hostages held by the Carthaginians, which helped him build good relationships with local tribes. For example, he returned a captured noblewoman to her fiancé, earning their loyalty and military support.

In 209 BC, Scipio continued to win over tribes. Indibilis and Mandonius, two powerful Celtiberian chiefs who had been loyal to Carthage, left Hasdrubal's camp. Hasdrubal realized he needed to act. He fought Scipio near Baecula. Scipio used clever tactics, attacking the Carthaginian wings before their main force was ready. Hasdrubal was defeated and fled towards Gaul, planning to join Hannibal in Italy.

Livy and Polybius, ancient historians, give slightly different accounts of the battle, but both agree on Scipio's victory. Scipio captured 10,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry. He sent the native prisoners home and sold the African ones. The native prisoners and local tribes saluted him as king, but Scipio said he preferred to be called "imperator" (victorious commander).

Scipio decided not to pursue Hasdrubal immediately. He sent a division to guard the Pyrenees. Hasdrubal Gisgo and Mago joined Hasdrubal too late. They decided that Hasdrubal Barca should go to Italy to help Hannibal, taking many Hispanic soldiers with him. Mago was to go to the Balearic Islands to hire mercenaries.

In 207 BC, a new Carthaginian commander, Hanno, arrived from Africa and raised a large army in Celtiberia. Scipio sent Silanus against him. Silanus surprised Hanno's camp, defeating his forces and capturing Hanno. This stopped the Celtiberians from siding with Carthage. Hasdrubal Gisgo retreated to Gades (Cadiz).

Scipio then sent his brother, Lucius Scipio, to attack Orongi, a rich city allied with Carthage. Lucius Scipio besieged the city. The townspeople, fearing a massacre, surrendered. The Romans entered without bloodshed.

In 206 BC, Hasdrubal Gisgo, with Mago's help, raised a huge army of 50,000 infantry and 4,500 cavalry. They camped near Ilipa (Seville). Scipio, with 55,000 men, faced them. For several days, both armies lined up in front of their camps. Scipio noticed that the Carthaginians always placed their African troops in the center and their Hispanic allies on the wings.

On the day of the battle, Scipio changed his formation. He put his Roman legions on the wings and his Hispanic allies in the center. He also started the battle earlier than usual. The Carthaginians were caught off guard and had to deploy quickly without eating breakfast. Scipio's wings attacked the Carthaginian wings rapidly, while his center advanced slowly. This meant the strong Roman legions fought the weaker Carthaginian wings first. The Carthaginian elephants also caused chaos among their own troops.

The Carthaginians, tired and hungry, were defeated. Hasdrubal fled with 6,000 men, many unarmed. The rest were killed or captured. Hasdrubal escaped by ship from Gades. This victory effectively expelled the Carthaginians from Hispania. Scipio returned to Tarraco.

Scipio then punished Castulo and Iliturgi, cities that had betrayed Rome. He besieged Iliturgi, which fell after a fierce fight. The city was destroyed. Castulo was also captured. Lucius Marcius continued to subdue other tribes. He defeated Astapa, a city that resisted fiercely, whose people chose to burn themselves and their possessions rather than surrender.

Scipio fell ill, leading to rumors of his death. This caused a mutiny among some Roman soldiers and a revolt by Mandonius and Indibilis. Scipio quickly showed he was alive, dealt with the mutiny, and then defeated Mandonius and Indibilis in battle. He spared them but demanded payment for his troops.

Scipio then met with Masinissa, a Numidian prince, and formed an alliance. Masinissa promised to help Rome if Scipio invaded Africa. Mago, the last Carthaginian commander in Hispania, received orders to go to Italy to help Hannibal. He tried to attack Cartago Nova but was repelled. When he returned to Gades, the city closed its gates to him. He then sailed to the Balearic Islands for the winter.

Resistance Against Rome Continues

After Scipio Africanus returned to Rome in 206 BC, he recommended that the Roman army stay in Hispania. Rome had made alliances with local tribes and needed to protect them. Also, these alliances could be unstable. So, a Roman military presence was necessary. Rome decided to stay in Hispania permanently. Scipio had set up permanent garrisons and founded a settlement for veterans called Italica. He also made the Roman army in Hispania self-sufficient, using war spoils and supplies from local tribes. This started the process of Romanization, bringing new products and technologies.

For seven years, Rome sent military commanders with unusual powers to Hispania. In 197 BC, two provinces were officially created: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior, each led by a praetor (a Roman official). However, because Rome was so far away, these governors often acted independently. This led to abuses and unfair treatment of local peoples, causing discontent and rebellions.

In 171 BC, envoys from Hispania complained to Rome about greedy Roman officials. They asked the Senate to stop these officials from treating them worse than enemies. The Senate set up trials to investigate these complaints. This was an early step towards holding Roman officials accountable for their actions in the provinces.

Another group of people, sons of Roman soldiers and local women, asked for a town to live in. The Senate allowed them to settle at Cartei, which became a "Colony of the Libertini" with special rights.

In 154 BC, new conflicts began in Hispania. This was the start of the Second Celtiberian War.

The Second Celtiberian War

This war started because Segeda, a powerful Celtiberian city, was building a very long wall. Rome saw this as breaking a treaty made by Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, which limited new fortifications. Segeda argued the treaty only forbade new towns, not fortifying existing ones. Rome prepared for war.

In 153 BC, the Roman praetor Quintus Fabius Nobilitor arrived with nearly 30,000 men. The people of Segeda fled to the Arevaci, another Celtiberian tribe. The Arevaci set an ambush in a thick forest, killing 6,000 Romans. From then on, Romans avoided fighting on the festival day of the god Vulcan, as this defeat happened then. The Arevaci gathered at Numantia, a city with strong natural defenses. Nobilitor attacked Numantia, but his elephants panicked during the battle, trampling Romans. The Numantines killed 4,000 Romans. These Roman losses encouraged other towns to rebel.

In 152 BC, Marcus Claudius Marcellus took command. He recaptured Ocilis and encouraged other towns to seek peace. He wanted to end the war himself. The Senate, however, sent a new consul, Lucius Licinius Lucullus, to continue the war. Marcellus quickly made peace with the Celtiberians before Lucullus arrived.

Lucullus, who was greedy, then attacked the Vaccaei tribe, even though Rome had not declared war on them. He pretended they were helping the Celtiberians. He besieged the town of Cauca (Coca). After the Caucaei surrendered and agreed to his terms, Lucullus ordered his soldiers to kill all the adult males, killing 20,000 people. He then attacked other towns, but faced strong resistance and supply problems. He got no gold or silver, which he had hoped to find.

Lucullus and Servius Sulpicius Galba, another Roman commander, also campaigned against the Lusitanians, killing many by treachery.

Lusitanian and Viriathic Wars

Lusitania (modern Portugal) was one of the last areas to be fully conquered by Rome. In 155 BC, the Lusitanian chief Punicus led raids against Roman-controlled areas. He won a major victory against Roman praetors.

After Punicus died, Caesarus took over and defeated Roman troops again. His victories showed other Iberian peoples that Rome could be beaten. Lusitanians, Vetones, and Celtiberians united against Rome. In 147 BC, a new Lusitanian leader named Viriathus rebelled. He used guerrilla warfare, striking the Romans fiercely without fighting open battles. He won many victories and became a hero in Portugal and Spain. Viriathus was assassinated around 139 BC, likely by his own men who were paid by a Roman general.

Between 135 and 132 BC, Consul Decimus Junius Brutus led an expedition into Gallaecia (northern Portugal and Galicia). Around the same time (133 BC), the Celtiberian city of Numantia, the last stronghold of the Celtiberians, was destroyed by Publius Cornelius Scipio Æmilianus. The people of Numantia were sold into slavery, and the city was completely destroyed.

The Numantine War

In 143 BC, the consul Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus attacked the Arevaci but could not take Termantia and Numantia. In 142 BC, the praetor Quintus Pompeius Aulus took over. He suffered several defeats in skirmishes and failed to capture Termantia. He then tried to divert a river to starve Numantia, but his men were constantly attacked.

Pompeius's army suffered from cold and disease during winter. Fearing he would be blamed for his failures, he secretly made a peace agreement with the Numantines. He demanded hostages, prisoners, and silver.

In 139 BC, a new consul, Marcus Popillius Laenas, arrived. Pompeius denied making the peace deal, but the Numantines proved he had. The Senate decided to continue the war. In 137 BC, the consul Gaius Hostilius Mancinus lost many battles to the Numantines. He panicked and made a disgraceful peace treaty, which angered Rome. He was recalled to stand trial.

Another consul, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus Porcina, attacked the Vaccaei without permission, falsely accusing them of helping Numantia. His siege of Pallantia failed, and his army suffered greatly from lack of supplies. He was stripped of his consulship and fined. In 135 BC, Quintus Calpurnius Piso achieved little against Pallantia.

In 134 BC, the Romans, tired of the war, elected Scipio Aemilianus (who had defeated Carthage) as consul. He was seen as the only one who could win. Scipio focused on restoring discipline in the Roman army through tough training. He then marched to Numantia. He built a massive nine-kilometer wall around the city with seven towers, completely cutting it off. He also blocked the river to prevent anyone from slipping through.

Scipio starved Numantia into surrender. He kept 50 men for his triumph, sold the rest into slavery, and destroyed the city. Appian, an ancient historian, noted the small numbers of Numantines and their great suffering, but also their brave deeds and long resistance against a much larger Roman army.

After the Lusitanian and Celtiberian Wars

The defeats of the Celtiberians and Lusitanians were big steps in Rome's control of Hispania. Rebellions continued, but they were smaller and less frequent.

Plutarch wrote that Gaius Marius operated in Hispania Ulterior in 114 BC, clearing out robbers. At that time, robbery was seen as an honorable job in some parts of Hispania.

In 98 BC, the consul Titus Didius was sent to Hispania. He killed about 20,000 Arevaci. He also moved a large city, Tarmesum, from easily defended hills to a plain and forbade them from building city walls. He besieged Colenda for nine months, captured it, and sold the people into slavery. He also tricked and killed a group of Celtiberian tribesmen who had been settled by a previous Roman commander.

In 82 BC, there was another Celtiberian rebellion. Gaius Valerius Flaccus was sent against them and killed 20,000.

These Roman governors often stayed in Hispania for many years, longer than usual. This might have been because of wars happening in Italy.

In 61 BC, Julius Caesar, while serving as praetor in Hispania Citerior, brought more tribes under Roman rule. Suetonius wrote that Caesar attacked and looted some Lusitanian towns to pay his debts, even though they had opened their gates to him peacefully.

Roman Civil Wars in Hispania

The Sertorian War

This civil war was fought in Hispania from 80 BC to 72 BC. It involved Quintus Sertorius, a Roman general who allied with native tribes, against the Roman government led by Sulla. Sertorius had opposed Sulla in Rome. He came to Hispania as a governor and gained control with his army. He defeated Sulla's forces and even campaigned in Africa.

Discontented Lusitanians chose Sertorius as their leader because he was sympathetic to them. He organized their tribes and won battles against Roman forces. Rome sent Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius to fight Sertorius. Sertorius used guerrilla tactics, wearing down Metellus. Other Roman commanders were also defeated by Sertorius's lieutenants. Eventually, Marcus Perperna, another Roman general who fled to Hispania, assassinated Sertorius. After Sertorius's death, Pompey defeated and captured Perperna, ending the war.

Julius Caesar's Civil War

In 49 BC, Julius Caesar invaded Italy, starting a civil war against the Roman Senate. Pompey, the Senate's leader, fled to Greece. Caesar marched quickly to Hispania to face Pompey's legions there. He defeated seven Pompeian legions at the Battle of Ilerda (Lerida) in northeastern Hispania.

The final battle of Caesar's Civil War was the Battle of Munda in southern Hispania in 45 BC. Caesar defeated Gnaeus Pompeius, Pompey's son. One year later, Caesar was assassinated.

Final Stage of Conquest: The Cantabrian Wars

The Cantabrian Wars (29–19 BC) were fought between the Romans and the Gallaeci, Cantabrians, and Astures tribes in northern Hispania. It was a long and bloody war because it took place in difficult mountains and the rebels used effective guerrilla tactics. The war lasted ten years and ended with these tribes being brought under Roman control. These wars marked the end of major resistance against the Romans in Hispania.

The reasons for this war are not entirely clear. We have little information about its early years. Ancient writers like Florus and Orosius mentioned that the Cantabri harassed their neighbors.

Augustus, the first Roman emperor, took command in 26 BC. He arrived in Tarraco (Tarragona) in 27 BC. He might have seen the war as a chance for military glory. He also needed to reorganize the Gallic provinces next door. The war also gave Rome control over rich gold mines in Asturia and iron ores in Cantabria.

Augustus began his campaign in 26 BC. Roman forces attacked from three directions. They fought battles, destroyed towns, and besieged the enemy. In 25 BC, Augustus became ill and retired to Tarraco. The war continued against the Astures. The Astures attacked Roman camps but were betrayed by one of their tribes. The Romans surprised them and captured their strongholds. In Rome, the Temple of Janus was closed, symbolizing peace. However, the Cantabri and Astures soon resumed fighting, and the war continued for another six years. Still, Augustus claimed victory.

The defeat of the Cantabri and Astures marked the end of resistance in Hispania. It seems that the rest of the peninsula had become well-integrated into the Roman system by then.

After the wars, Augustus officially made the whole peninsula part of the Roman Empire. Hispania Citerior was greatly expanded and renamed Hispania Tarraconensis. Hispania Ulterior was divided into Baetica and Lusitania.

Many Roman veterans were settled in Hispania after the wars. Several Roman towns were founded, including Augusta Emerita (Mérida), Asturica Augusta (Astorga), Caesaraugusta (Zaragoza), and Lucus Augusti (Lugo). Augustus also commissioned the via Augusta, a long road from the Pyrenees to Cadiz.

See also

In Spanish: Conquista de Hispania para niños

In Spanish: Conquista de Hispania para niños