Mercenaries of the ancient Iberian Peninsula facts for kids

Imagine a warrior who fights for money, not for their home country. This is a mercenary. Long ago, during the Iron Age in what is now Spain and Portugal (the Iberian peninsula), many young people became mercenaries. They often came from poor families. Fighting for other groups was a way to escape poverty. It also let them use their fighting skills.

Starting around 500 BC, being a mercenary became very popular in this region, called Hispania. Many fighters from Hispania joined armies far away. They fought for Carthage, Rome, Sicily, and even Greece. They also fought for other groups within Hispania.

Writers like Strabo and Thucydides said these Iberian fighters were among the best in the Mediterranean Sea area. Livy even called them the most skilled part of Hannibal's army. Polybius wrote that they helped Carthage win many battles during the Second Punic War.

Contents

Why People Became Mercenaries

It can be hard to tell the difference between a true mercenary and a foreign fighter who joined an army through a deal. Ancient records often use general terms for people from the Iberian peninsula. But we know that Hispania became a major source of mercenaries during the early Iron Age.

The main reason was money. Many young people left their tribes to fight for richer groups. This helped them escape poverty in their own lands. These areas often had big differences between rich and poor. For example, in Lusitania and Celtiberia, only a few people owned most of the good land. Becoming a mercenary was often the only choice besides becoming a bandit.

However, the long history of tribal warfare and a strong warrior culture in Hispania also played a part. People from the Balearic Islands and the mountains of Cantabria were also known for being great mercenaries.

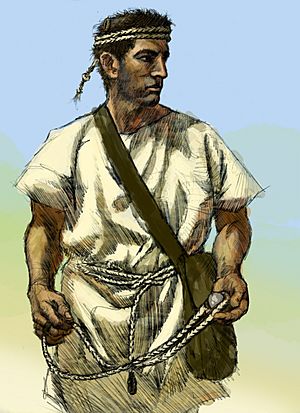

Hispanic mercenaries usually worked in small groups. These groups were made up of friends and family. They had their own leaders and kept their own fighting styles and weapons. Not all mercenaries returned home. Some, like those from the Balearic Islands, spent all their money. But if they did return, they were seen as heroes. This was because their societies valued warriors.

Sometimes, they didn't go abroad. They just went to richer parts of Hispania, like Turdetania. Important war chiefs from the south, like Indortes and Istolatius, were Celts hired by the Turdetanians. But the most famous Hispanic mercenaries fought for Carthage, Rome, and Greek countries.

Important places for hiring these fighters were Gadir, Empúries, Castulo, and the Balearic Islands. Hispanic mercenaries were wanted because they were tough, disciplined, and skilled. They also had a fierce reputation.

Early Mercenaries (5th–4th Centuries BC)

The first mentions of Spanish mercenaries are from the Sicilian Wars (460-307 BC). They fought for the Carthaginian military in Sicily. They might have worked for Carthage as early as 535 BC. But their first big role was in the Battle of Himera in 480 BC. Writers like Diodorus and Herodotus say they were part of Hamilcar I's army against the Greeks.

After that battle, the Hispanic fighters were the only Carthaginian troops to regroup. They defended their camp and caused heavy losses for the Greeks. Later, they led attacks on cities like Selinus and Himera. They also fought in other major battles and sieges.

The Greeks were impressed by their success. So, they started hiring Hispanics too. Some fought in the Peloponnesian War for the Peloponnesian League. Others helped in the Athenian coup of 411 BC.

In 396 BC, a Carthaginian general named Himilco left his mercenaries behind in Sicily. The Hispanic fighters were the only ones who survived. They formed a battle group and offered their services to Dionysius I of Syracuse. Dionysius was so impressed that he hired them as his personal guards. Later, his son Dionysius II sent some of these Celts and Iberians to help the Spartans in the Theban–Spartan War. They were very effective.

In 361 BC, Plato saw a small rebellion by Dionysius II's mercenaries. They were upset about their pay. They marched towards the king's palace, singing their war songs. Dionysius II was so scared that he gave them even more money than they asked for. Balearic slingers also fought for Carthage in the 311 BC Battle of the Himera River.

Mercenaries in the 3rd Century BC

In 274 BC, Hiero II of Syracuse decided to stop hiring mercenaries in Sicily. He wanted to prevent more rebellions. He sent them to fight the Mamertines, a group of Italian raiders. He then left them to be defeated. However, he likely still hired some Hispanic mercenaries later.

Carthaginian mercenaries from Hispania returned to Sicily during the First Punic War in 264 BC. After Carthage lost the war, these mercenaries were sent to Africa to be paid. But Carthage couldn't pay them due to money problems caused by Rome. This led to the Mercenary War, where the mercenaries rebelled. Carthaginian forces, led by Hamilcar Barca, defeated them.

The Second Punic War was when Iberian mercenaries became very important again. This was because Hispania was a main battleground in that war.

When Hamilcar Barca arrived in Hispania in 237 BC, he conquered many tribes. He also gained many fighters from them. His son Hannibal continued this after Hamilcar's death. Hannibal planned to lead an army to Italy. It's hard to tell if these fighters were true mercenaries or just people forced to join. But it seems Hannibal paid those who weren't from conquered lands.

In 218 BC, before leaving Cartagena, Hannibal sent 16,000 fighters from certain tribes to guard Carthage. In return, he got 15,200 African javelin throwers. He did this to prevent any rebellions far from their homes. He also let many people from Carpetania go home if they didn't want to leave Hispania. This way, Hannibal kept only the most loyal fighters, including mercenaries.

It's thought that between 8,000 and 10,000 Hispanic fighters reached Italy with Hannibal. Most of them were likely still alive and fighting when he returned to Carthage in 202 BC. This shows how reliable they were.

The exact types of mercenaries are not fully known, but Celtiberians, Lusitanians, and Balearics were key groups. Hannibal used them for their special skills. Celtiberians were good heavy cavalry and strong infantry. They were known for holding their ground in battles like Cannae. Lusitanians were good mountain troops and could be both skirmishers and heavy cavalry. Their combined force of about 2,000 horsemen was highly praised.

Balearics, numbering between 1,000 and 2,000, were excellent skirmishing infantry. They used slings to throw heavy stones with great force. Some writers mention even more tribes, but Celtiberians and Lusitanians were likely the main mercenary groups.

Other Celtiberians fought against Carthage after making a deal with Rome. They defeated Hasdrubal Barca's forces in 217 BC. Four years later, they became the first mercenaries hired by Rome. Publius Cornelius Scipio hired them to keep their loyalty. He even sent 200 of them to Italy to try and convince their countrymen in Hannibal's army to switch sides. This didn't work well, but it might have made Hannibal trust them less.

Hasdrubal, knowing the Hispanic tribes better, managed to bribe Scipio's mercenaries. They agreed to leave the Roman general, though they wouldn't fight against him. This led to Scipio and his brother being killed in 211 BC.

Later, some Celtiberian commanders betrayed the Syracusians (who were allied with Carthage) and joined the Romans. Another group of 1,000 Hispanics also joined the Roman side in Arpi. These were rare exceptions, as Hispanic mercenaries were usually very loyal to Hannibal. Hannibal saw his Iberian fighters as very valuable, almost as important as his African troops. They were much more reliable than the less disciplined Gauls and Ligurians.

In 209 BC, Hasdrubal gathered many Celtiberian and Cantabrian mercenaries. He left Hispania for Italy to meet Hannibal. His army arrived in 207 BC but was defeated in the Battle of the Metaurus. Hasdrubal was killed among the Iberian fighters, who were the last Carthaginian forces to fall. Some Celtiberians managed to escape and reach Hannibal.

Later that year, generals Mago Barca and Hanno went to Celtiberia to raise another army. But a new Roman attack, led by Marcus Junius Silanus, stopped them. This was a difficult choice for Rome, as entering Celtiberian lands made them enemies again. Mago escaped with 2,000 survivors. After the Battle of Ilipa, he tried to gather another Celtiberian group, but this attempt also failed. The remaining mercenaries, now 12,000, were put on a fleet by Mago. They sailed towards Italy, picking up 2,000 Balearics along the way.

The last major uses of Iberian mercenaries in the Second Punic War were in defending Carthage. They fought briefly after the Battle of Utica. Soon after, Hasdrubal Gisco and Syphax led 4,000 Celtiberians against the Romans in the Battle of the Great Plains. The Celtiberians fought fiercely, knowing the Romans would not spare them. Most of them fought to the end and died in battle.

There were more attempts to bring Hispanic fighters to Carthage. But the Saguntines captured the Carthaginian recruiters and sold them to Rome. In 202 BC, Hannibal brought his remaining veteran mercenaries from Italy. He joined them with Mago's troops (Mago had died at sea). They faced Scipio again in the Battle of Zama. They were defeated, and the war ended. Carthage's loss meant the end of their mercenary tradition, as Rome made it a condition of peace.

Later Mercenaries (2nd–1st Centuries BC)

Even after Carthage left Hispania, the custom of mercenary life continued. Between 197 and 195 BC, the Turdetanians used 30,000 Celtiberians as elite troops during the Iberian revolt. In 147 BC, the Romans themselves sent Celtiberians against the Lusitanians led by Viriathus, but they were not successful. Julius Caesar also used Balearic slingers in the Gallic Wars.

Mercenaries in the Roman Empire (1st–4th Centuries AD)

Balearic slingers continued to be hired as mercenaries in the Imperial Roman army. Their skill with slings was valued even as late as the 4th century AD. By this time, slingers were recruited from other places besides Iberia and the Balearic Islands.

See also

In Spanish: Mercenarios de la antigua península ibérica para niños

In Spanish: Mercenarios de la antigua península ibérica para niños

- Warfare in the ancient Iberian Peninsula

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |