Iberian revolt facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Iberian revolt (197-195 BC) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula | |||||||||

A warrior from Iberia with a special sword and shield. This artwork is from the Osuna sculptures. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Iberian rebels:

|

|||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

The Iberian revolt (197-195 BC) was a big uprising by the local people of Iberia. They lived in areas that Rome had recently turned into provinces called Citerior and Ulterior. The revolt was against the Roman rule in the 2nd century BC.

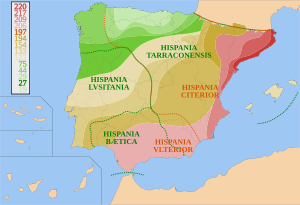

In 197 BC, the Roman Republic divided its newly won lands in southern and eastern Iberian Peninsula into two provinces. Each province was ruled by a Roman official called a praetor. The main reason for the revolt was likely the new rules and taxes that came with becoming Roman provinces.

The rebellion started in the Ulterior province. Rome sent two praetors, Gaius Sempronius Tuditanus to Citerior and Marcus Helvius Blasio to Ulterior. Sadly, Gaius Sempronius Tuditanus was killed in battle before the revolt reached his province. However, Marcus Helvius Blasio won an important victory against the Celtiberians at the Battle of Iliturgi. The situation was still not under control. So, Rome sent two more praetors, Quintus Minucius Thermus and Quintus Fabius Buteo. They won some battles, like the Battle of Turda, where Quintus Minucius even captured the Hispanic general Besadino. But they still couldn't fully end the revolt.

Because of this, in 195 BC, Rome had to send the famous consul Marcus Porcius Cato. He led a large army to stop the revolt. When he arrived in Hispania, almost all of the Citerior province was rebelling. Only a few Roman-controlled cities were left. Cato made a deal with Bilistages, the king of the Ilergetes. He also had help from Publius Manlius, who was the new praetor for Hispania Citerior.

Cato sailed to the Iberian Peninsula and landed at Rhode. He quickly stopped the rebellion there. Then he moved his army to Emporion. This is where the biggest battle of the war happened. The local army was much larger than Cato's. After a long and tough fight, Cato won a complete victory. He caused about 40,000 casualties to the enemy. After this huge win, the Citerior province came back under Roman control.

However, the Ulterior province was still out of control. Cato had to go to Turdetania to help the praetors Publius Manlius and Appius Claudius Nero. Cato tried to make a deal with the Celtiberians, who were fighting as paid soldiers for the Turdetani. He wanted them to join his side, but they refused. After showing his strength by marching his Roman Legions through Celtiberian land, he convinced them to go back home. But the local army only pretended to give up. When rumors spread that Cato was leaving for Rome, the rebellion started again. Cato had to act fast and effectively. He finally defeated the rebels in the battle of Bergium. After this, Cato sold the captured rebels into slavery. The local people of the province were also disarmed.

Contents

How the Revolt Started

The Second Punic War was almost over. The Carthaginian generals Magon Barca and Hasdrubal Gisco had gone back to Gades. This allowed Scipio Africanus to take control of all of southern Iberian Peninsula. Scipio then went to Africa to meet with the Numidian king Syphax. He wanted to form an alliance with him.

Soon after, Scipio became very ill. About 8,000 Roman soldiers used this chance to rebel. They were unhappy because they got less pay than usual. Also, they were not allowed to take things from enemy towns. This mutiny was a perfect chance for the Ilergetes and other Iberian groups to revolt. Their leaders were Indibilis (from the Ilergetes) and Mandonius (from the Ausetani). This rebellion was mainly against the Roman officials Lucius Cornelius Lentulus and Lucius Manlius Acidinus.

Lucius Manlius managed to defeat the Ausetani and Ilergetes. They had rebelled against the Roman Republic while Scipio Africanus was away. Lucius Manlius returned to Rome in 199 BC. But he was not given the special honor that the Roman Senate had planned for him. This was because a Roman official named Publius Porcius Laeca was against it. Scipio Africanus managed to stop the soldiers' mutiny. He also ended the Iberian revolt in a bloody way. Mandonius was captured and killed in 205 BC, but Indibilis escaped.

Magon Barca and Hasdrubal Gisco left Gades with their ships and troops. They went to the Italian Peninsula to help Hannibal. After they left, Rome controlled all of southern Hispania. Rome now ruled from the Pyrenees mountains down to the Algarve coast. The Roman armies controlled land as far as Huesca, and from there south to the Ebro river and east to the sea. Rome's victory over Carthage in the Second Punic War meant they now fully controlled Hispania.

When Scipio Africanus left Hispania, the Iberian chiefs who had supported him felt they only had a personal connection to him. They didn't feel loyal to the Roman Republic. So, they took up arms against Rome. Other reasons for the uprising have been suggested. These include the deaths of Indibilis and Mandonius by the Romans. But the most common reason given is the high taxes the people of Hispania had to pay to Rome. This was especially true after their land was made into two provinces.

Armies in the Fight

| Hispanic Armies | Roman Armies | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Soldiers | Number | Type of Soldiers | Number |

| Battle of Iliturgi: | Praetor of Hispania Citerior: | ||

| Celtiberians | 20,000 | Foot soldiers (regular troops) | 4,000 |

| Battle of Turda: | Horsemen (regular troops) | 200 | |

| Iberians | + 12,000 | 1 Legion (extra troops 196 BC) | 4,200 |

| Battle of Emporion: | Foot soldiers (extra troops 196 BC) | 2,000 | |

| Iberians (likely Indigetes) | 40,000 | Horsemen (extra troops 196 BC) | 150 |

| Turdetania: | Foot soldiers (extra troops 195 BC) | 2,000 | |

| Celtiberians | 10,000 | Horsemen (extra troops 195 BC) | 200 |

| Turdetani | Unknown number | Praetor of Hispania Ulterior: | |

| Foot soldiers (regular troops) | 4,000 | ||

| Horsemen (regular troops) | 200 | ||

| 1 Legion (extra troops 196 BC) | 4,200 | ||

| Foot soldiers (extra troops 196 BC) | 2,000 | ||

| Horsemen (extra troops 196 BC) | 150 | ||

| Foot soldiers (extra troops 195 BC) | 2,000 | ||

| Horsemen (extra troops 195 BC) | 200 | ||

| Main Roman Army: | |||

| 2 Legions | 8,400 | ||

| Horsemen | 800 | ||

| Allies | 15,000 | ||

| Total | + 82,000 | ~ 50,000 | |

First Battles

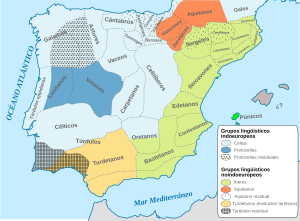

In 197 BC, the Roman Republic divided its lands in southern and eastern Iberian Peninsula into two provinces. These were Hispania Citerior (the east coast, from the Pyrenees to Cartagena) and Hispania Ulterior (roughly modern-day Andalusia). Each was ruled by a praetor. The change to provinces brought new rules and taxes. The local tribes did not like the new taxes. So, in 197 BC, a big revolt started across the Roman-controlled area in Hispania.

The new provinces needed rulers. So, the Roman Republic sent praetors Gaius Sempronius Tuditanus to Hispania Citerior and Marcus Helvius Blasion to Hispania Ulterior. They brought 8,000 foot soldiers and 800 horsemen. Their job was also to mark the borders of the provinces. When Marcus Helvius arrived, he found a large revolt. He told the Roman Senate about it. Many local chiefs had rebelled in Hispania Ulterior. Among them were the leader Culcas, who commanded armies from 17 cities, and leader Luxinio, who led forces from Carmo and Bardo. The cities of Malaca, Sexi, and all of Baeturia had also joined the revolt.

Soon after, the war spread from the Ulterior province to the Citerior province. Its praetor, Gaius Sempronius Tuditanus, died from battle wounds in late 197 BC. Many soldiers also died. The province was left without a praetor until the next year. It's likely that Marcus Helvius, the praetor of Ulterior, took control of Citerior until a new praetor arrived.

Quintus Minucius Thermus and Quintus Fabius Buteo were chosen as praetors in 196 BC. They were put in charge of Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior. They received extra troops: two legions, 4,000 foot soldiers, and 300 horsemen. They were told to go quickly to the provinces to continue the war. Quintus Minucius Thermus defeated the rebel leaders Budar and Besadines at a place called Turda. He caused 12,000 casualties among the Hispanic forces and captured General Besadines. Because of this, Quintus Minucius received a special honor called a triumphus when he returned to Rome in 195 BC.

Roman Victory at Iliturgi

The praetor in Hispania Citerior in 196 BC had limited success. So, the Roman Senate declared it a "consular province." This meant a large army led by a consul was needed to control the situation. Marcus Porcius Cato, the Elder was chosen as consul in 195 BC. He was given charge of Hispania Citerior. His friend Lucius Valerius Flaccus was also elected consul.

Praetors for Hispania Ulterior and Hispania Citerior were also chosen. They were Appius Claudius Nero and Publius Manlius. They received extra troops: 2,000 more foot soldiers and 200 more horsemen. These were added to the legions their predecessors had. Consul Marcus Porcius Cato sailed with his troops to Hispania. He took charge of the Citerior province with Publius Manlius helping him. Appius Claudius was left in charge of the Ulterior province.

Marcus Helvius Blasion had already given control of his province to his successor. But he had to stay in Hispania because of a long illness. Once he recovered, he had 6,000 soldiers given to him by praetor Appius Claudius Nero. He was then attacked by 20,000 Celtiberians near Iliturgi. Marcus Helvius managed to fight them off and defeat them. He caused about 12,000 casualties to the enemy. Iliturgi was taken by the Romans. This victory earned Marcus Helvius Blasion a special honor called an ovatio from the senate in 195 BC. However, he couldn't have a full triumphus because he fought in a province that belonged to another praetor. When he arrived in Rome, Marcus Helvius gave the Roman Republic a lot of silver. This amount of wealth taken from Hispania shows how upset the local people were, which was likely why they rebelled.

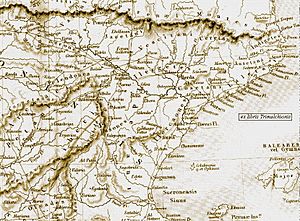

Cato Lands in Hispania

The Roman Senate gave Marcus Porcius Cato the Elder a large army. It had two legions, 8,000 foot soldiers, 15,000 allies, and 800 horsemen. He also had 20 ships to carry the troops. On top of this, each praetor got 2,000 more foot soldiers and 200 more horsemen. This made a total of about 50,000 men among the three armies. Cato sailed his army on 25 ships, 5 of which carried allied troops. They left from Portus Lunae (Luni, Italy) and sailed along the Gulf of Leon. They reached Hispania, in the northern part of the Citerior province. The Roman army landed at Rhode, in the Gulf of Roses, around June 195 BC. They defeated a local army there. When Cato arrived in Hispania, the military situation was difficult. He personally had about 20,000 men, as the rest were with the praetors. So, Cato faced the battle with these forces.

Siege of the Citadel

Iberian settlements were usually built on hills. These were strategic spots that controlled pathways. This gave them a big advantage against enemies. They were often surrounded by strong walls with watchtowers and city gates.

The city finally fell in July 195 BC. Cato looted the city. Then he fought against the local people and ended the resistance of the Iberian soldiers. These soldiers were in the fortress on Puig Rom, or Rhode acropolis, which was likely the Citadel of Roses.

Roman Army Reaches Emporion

Cato said, "War feeds itself." This means that war can provide what it needs, so he refused to buy extra supplies for his army.

Marcus Porcius Cato would face a tough fight in Emporion. This city was almost an island, surrounded by marshes. A Greek city and an Iberian city existed side-by-side, separated by a wall. When Cato and his troops arrived, the Greek people welcomed them warmly.

Meeting with Ilergetes Allies

At this time, three messengers from the Ilergetes arrived at the Roman camp. One of them was the son of King Bilistages. They told the consul that their Ilergetes cities were under attack. They said they couldn't hold out without immediate help. They asked for at least 3,000 men. Cato replied that he understood their danger. But he had to fight a big battle and couldn't spare any soldiers. The Ilergetes begged for help. They said they had no allies except Rome. They were the only ones loyal to the Roman Republic, and all other local peoples were now their enemies. The messengers left the camp disappointed.

The consul didn't want to abandon his allies. But he also couldn't leave soldiers behind. So, he came up with a plan to give the Ilergetes hope. This would make them fight with more courage. The next morning, Cato called the messengers and told them he would help. He ordered a third of his soldiers to get ready to help the Ilergetes in two days. He did the same with the ships. The messengers left the camp after seeing the soldiers get on the ships. After a careful amount of time, Cato ordered the soldiers to leave the ships.

Cato stayed outside the city for a few days. He studied the enemy troops and trained his soldiers. During this time, Marcus Helvius visited the camp. He was on his way back to Rome. He was protected by 6,000 soldiers borrowed from praetor Appius Claudius. Since the area was now safe, Helvius returned the men to Appius Claudius and sailed for Rome.

Preparing for the Big Battle

When Cato felt his soldiers were ready to fight the local people in the open field, he ordered them to a second camp. This camp was 3,000 paces from the city, in enemy territory. From there, he attacked the rebels at night. He burned their fields and took their crops and animals. This lowered the enemy's morale. It also trained his soldiers. The enemies became so scared that they dared less and less to leave the city. Also, the consul ordered 300 soldiers to capture an enemy guard for questioning.

Cato's army started with about 20,000 men. They had lost some soldiers in the battle of Rhode. The local army besieging Emporion had about 40,000 men. Many of them had left to help with the harvest. Marcus Porcius Cato took advantage of this moment to attack their camp.

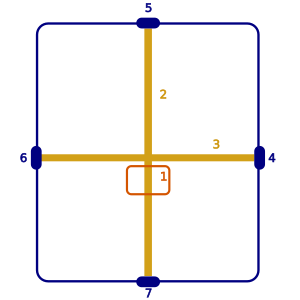

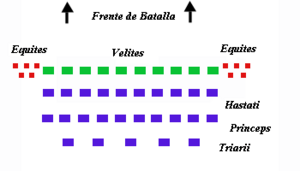

Cato's Battle Plan

During the night, Cato took the best position. He kept one legion in reserve. He placed the cavalry (horsemen) at the ends of his line and the foot soldiers in the middle. This was a typical setup for a "maniple army" from the Republican era. The maniples were organized into three battle lines. Each line had a different type of heavy foot soldier. The hastati were soldiers with leather armor, breastplates, and helmets. They formed the front line. They carried a wooden shield with iron, a sword called a gladius, and two throwing spears called pila.

The princeps were heavy foot soldiers. They usually formed the second line. They had similar weapons and armor as the hastati, but wore lighter chain mail. In the third line were the triarii. Their weapons and armor were like the princeps, but their main weapon was a pike instead of two pila. Finally, the equites (horsemen) were placed on both sides of the battle formation.

The Iberian warriors had more soldiers. They also had strong weapons. These included the gladius, falcata, the soliferrum, and the pugio (a dagger that Rome later used).

Historians have often praised the quality of Iberian weapons, especially their swords.

The Battle Unfolds

Early in the morning, Cato the Elder sent three cohorts to the back of the Iberian camp. This surprised the Hispanic forces, who didn't expect an attack from behind. The Roman army then positioned itself between the enemies and its own camp. Cato used this move to force his men to fight, preventing them from running away. Cato then ordered his attackers to pretend to retreat. The Iberians chased them in a messy way, rushing outside their camp. At this point, the Roman cavalry appeared on their right side. However, the cavalry was overwhelmed and retreated in fear. Part of the foot soldiers also retreated. So, Cato had to send two more cohorts to help. These cohorts were to surround the attackers on the right before the main lines of foot soldiers met.

The fear caused in the Hispanic troops by this move was similar to the initial fear of the Roman cavalry. The battle was very even when fought with throwing weapons. On the right side, the Iberians were winning. But on the left and in the center, the Romans were stronger. They were also waiting for two more cohorts to arrive. As the battle remained even, in the evening, Cato attacked in a wedge formation. He used three reserve cohorts that had been waiting in the second line. This created a new battle front and caused the Iberians to break apart. Cato ordered the second legion, which had stayed at the back, to form up. He attacked the enemy camp at night. The fresh legion arrived and gathered at the camp fence. The Hispanic forces fought fiercely to protect it. Cato then noticed that the Iberian resistance was weakest at the left gate. So, he ordered the hastati and princeps of the second legion to move towards it.

The defenders of the gate couldn't hold out, and the Romans got in. Taking advantage of the confusion, the rest of the legion finished off the defenders. The Roman army won a complete victory. According to Valerius Antias, the Hispanic forces suffered 40,000 casualties in the battle. Once the fighting was over, the consul let his men rest. He then sold the large amount of captured goods.

After the battle, not only the people of Emporion surrendered, but also those from nearby cities. Cato treated them well and even helped them. Then he let them go home.

End of Fighting in Citerior Province

With the victory at Emporion, Marcus Porcius Cato had brought peace to all of Hispania Citerior. All the cities up to Tarraco surrendered to him. They also handed over any Romans they held as prisoners.

Soon after, news spread that the consul was leaving with his army for Turdetania. Some Bergistani people used this chance to rebel again. Cato easily stopped their revolt twice. But he was not so kind the second time. He sold the defeated rebels into slavery. Cato's tactic was to reach the villages faster than expected. This allowed him to surprise the rebels. After this, Cato ordered all the people in the Citerior province to give up their weapons.

The consul called together leaders from the Hispanic cities. He asked them to take steps to prevent future rebellions against Rome. When the Hispanic leaders didn't respond, Cato ordered the walls of all the cities to be torn down.

The War in Ulterior Province

Turdetani Revolt

The praetors Appius Claudius Nero and Publius Manlius were in Turdetania. They were fighting against the Turdetani people and the Celtiberians who were hired as mercenaries. They won some battles. These victories were not too hard because the praetors had many horsemen and experienced soldiers. But later, the Turdetani hired another 10,000 Celtiberians. They began to prepare for battle again.

After a successful campaign, Cato led his troops to Sierra Morena, in Turdetania. He went to help the praetors Publius Manlius and Appius Claudius. This was in the area where the Turdetani had their mines. The Turdetani and Celtiberians (who were paid soldiers for the Turdetani) were camped in different places. At first, there were some small fights between Romans and Turdetani. The Romans always won. Cato sent his officers to try and convince the Celtiberians to leave without fighting. He also offered them double the pay if they joined the Roman army. The Celtiberians asked for time to think. But when the Turdetani joined the meeting, no agreement was reached. However, the Celtiberians decided not to fight. After losing the Celtiberian soldiers, the Turdetani were defeated. This defeat meant they lost their mines. It forced the Turdetani to stay in the Guadalquivir valley, where they focused on farming and raising animals.

Marching Through Celtiberia

Cato the Elder went back north through Celtiberia. He wanted to scare the Celtiberians and stop future uprisings. This was also punishment for them joining the Turdetani revolt. He went towards Segontia. He heard there was a lot of treasure there. He tried to besiege the city but didn't have enough time. Then he went towards Numantia. Near there, he gave a speech to his horsemen.

He later returned to the Citerior province. He left part of his army with the praetors after paying his soldiers. He took seven cohorts with him.

Returning from Turdetania, Cato made the ausetani, suessetani, and sedetani surrender. The consul used the unhappiness of his allies with the Lacetani. The Lacetani had raided their villages while the Romans were in Turdetania. When the Roman group reached the Lacetani city, Cato sent some of his cohorts to one side and others to the opposite side. Then he ordered his allies, mostly Suessetani, to attack the wall. The Lacetani thought they could easily defeat the Suessetani. They opened a gate and went out to meet them. The Suessetani ran away, and the enemies chased them. Then the consul ordered his cohorts to enter the town right away. They surprised the Lacetani. After this, the Lacetani surrendered.

Third Uprising of the Bergistani

Later, the consul Marcus Porcius Cato headed back to the Citerior province. He went to the land of the Bergistani, who had rebelled again. They were holding out in the fortress of castrum Bergium. When he arrived at the city, the Bergistani leader went to Cato. He told Cato that he and his people were still loyal to Rome. He said that outsiders had taken control of the city and were hostile to the Romans. He also said they were stealing from the people of the Citerior province.

Cato then came up with a plan to test if the Bergistani were loyal to him. This would also help him conquer the city more easily. Cato ordered the Bergistani leader and his loyal followers to take over the citadel when the Roman siege began. The Bergistani did this. The bandits were then surrounded and defeated. After the battle, Cato ordered that the citizens who had been loyal to his plan be set free. The remaining Bergistani were enslaved, and the foreign bandits were executed.

What Happened Next

Managing the Victory

After defeating the Hispanic rebels between the Iberus River and the Pyrenees, Cato the Elder focused on managing the province. During his rule, government income increased. This was because the state made more money from mining resources, mainly silver and iron. They also made a lot of money from salt, which the consul was interested in. It seems Cato understood why the revolt happened, likely because of the very high taxes on the people of Hispania. So, he changed how taxes were collected, increasing the profit that stayed in Hispania.

While Cato was still in Hispania, a new consul and new praetors were chosen in Rome. Scipio Africanus, Cato's rival, was again elected consul. Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica was chosen as praetor for Ulterior, and Sextus Digitius for Citerior. Scipio wanted to be sent to Hispania. But the Roman Senate decided that the new consul should go to Italy. This was because the Hispanic provinces had been made peaceful.

Because of Cato's successes in Hispania, the senate approved three days of public prayers. They also decided that the soldiers who had fought in Hispania during the revolt should be released from duty.

In late 194 BC, Marcus Porcius Cato returned to Rome. He brought a huge amount of treasure from the war. This included silver and gold, all taken from the Hispanic peoples during his military actions. This is recorded in the Fasti triumphales. Cato shared some of the treasure among the soldiers who had served under him.

Winning the war in Hispania greatly helped Marcus Porcius Cato's career. It allowed him to reach the same level as his opponents. This success meant he could compete with his great rival Scipio Africanus.

After Cato the Elder returned to Rome and the new praetors arrived in the Hispanic provinces, another rebellion happened. The praetor Sextus Digitius fought many times with the rebels. He lost up to half of his troops in the fighting.

Continuing the Conquest

Celtiberia

In Hispania, the Romans continued their conquest after Cato's actions. The Roman official Marcus Fulvius Nobilior later fought other rebellions. Then Rome began to conquer Lusitania. They had two important victories: in 189 BC by the official Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus, and in 185 BC by the praetor Gaius Calpurnius Pisonus.

The conquest of Celtiberia began in 181 BC with Quintus Fulvius Flaccus. He managed to defeat the Celtiberians and take control of some areas. For this, he received a special honor in 191 BC. However, most of the conquest and pacification was done by praetor Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus from 179 BC to 178 BC. Sempronius took about thirty cities and villages. He used different strategies, sometimes making deals and sometimes causing rivalry between Celtiberians and Vascones. He also founded the new city of Gracchurris on top of the existing city of Ilurcis.

Lusitania

Later, problems came from Lusitania. From 155 BC, Punicus led major campaigns in areas controlled by the Roman Republic. He raided lands in Baetica and reached the Mediterranean Sea coast. The Vettones were his allies. He won big victories, like against the Roman praetors Marcus Manlius and Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus.

From 147 BC, the republic had to face a new Lusitanian enemy, Viriathus. He was a shepherd at first, but then became a big problem for Rome. He was even called "the terror of Rome." He managed to escape a massacre by Servius Sulpicius Galba in 151 BC. Later, he rebelled and won several victories against the Romans. He also conquered several cities, like Tucci (likely modern-day Martos or Tejada la Vieja), and the region of Bastetania. He was killed around 139 BC.

See also

In Spanish: Revuelta íbera para niños

In Spanish: Revuelta íbera para niños

- Portal:Ancient Rome

- Campaign history of the Roman military

- Structural history of the Roman military

- Kingdom of Iberia

- Roman Republic

- Carthaginian Iberia

Images for kids

-

Parallel Lives, by Plutarch.

-

Titus Livius, author of Ab Urbe condita libri.

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |