History of Portuguese facts for kids

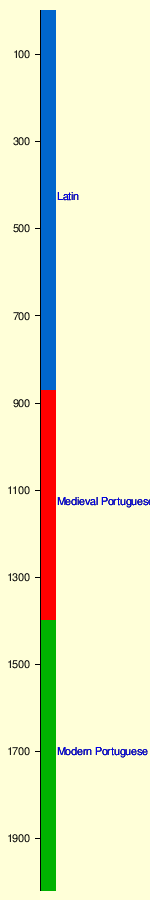

The Portuguese language grew in the Western Iberian Peninsula from Latin, which was spoken by Roman soldiers and settlers. This started around the 3rd century BC.

Old Portuguese, also called Medieval Galician, began to change from other Romance languages after the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the Germanic invasions in the 5th century. It started appearing in written papers around the 9th century. By the 13th century, Galician-Portuguese had its own stories and poems. It then began to split into two languages. However, people still debate if Galician and Portuguese are different types of the same language today, like American English and British English.

In almost every way – its sounds (phonology), word structure (morphology), words (lexicon), and sentence structure (syntax) – Portuguese is mainly the result of Vulgar Latin changing over time. It also got some influences from other languages. These include the native Gallaecian and Lusitanian languages spoken before the Romans arrived.

|

Contents

How Portuguese Grew Over Time

Roman Influence

The Romans arrived in the Iberian Peninsula in 218 BC. They brought with them Latin, which is the root of all Romance languages. Roman soldiers, settlers, and merchants helped spread the language. They built Roman cities, often near older towns. Later, people in cities like Lusitania and other Romanized parts of Iberia became Roman citizens.

The Romans didn't fully control the western part of Hispania until Augustus's campaigns in 26 BC. Even though wars with the Carthaginians and local people lasted 200 years, only about 400 words from native languages remain in modern Portuguese. Emperor Augustus conquered the whole peninsula, naming it Hispania. He divided it into three provinces: Hispania Tarraconensis, Hispania Baetica, and Lusitania. Lusitania included most of modern Portugal. Later, Emperor Diocletian created the province of Gallaecia, which covered the rest of Portugal and modern Galicia in Spain.

Germanic and Arabic Changes

Between AD 409 and 711, as the Roman Empire fell, Germanic tribes like the Suevi and Visigoths invaded the Iberian Peninsula. They mostly adopted Roman culture and language. However, Roman schools and government closed, allowing the everyday Latin language to change on its own. The language across the peninsula started to become different. In the northwest (today's Northern Portugal and Galicia), Latin began to develop local features, becoming what we call Galician-Portuguese.

Germanic languages added words to Galician-Portuguese. These words were often related to the military, like guerra (war). They also included place names like Resende, animals like ganso (goose), and feelings like orgulho (pride).

From 711, the Moorish invasion brought Arabic to the Iberian Peninsula. Arabic became the official language in the areas they conquered. But many people still spoke Latin-based dialects, known as Mozarabic. Arabic mainly influenced the words used in Portuguese. Modern Portuguese has 400 to 800 words from Arabic. Many of these came through Mozarabic. These words are often about food, farming, and crafts. Arabic influence is also seen in place names, especially in southern areas like the Algarve and Fátima.

However, no Arabic words are found for human feelings or emotions. Those words are all from Latin, Germanic, or Celtic origins.

| Excerpt of medieval Portuguese poetry |

|---|

| Das que vejo |

| non desejo |

| outra senhor se vós non, |

| e desejo |

| tan sobejo, |

| mataria um leon, |

| senhor do meu coraçon: |

| fin roseta, |

| bela sobre toda fror, |

| fin roseta, |

| non me meta |

| en tal coita voss'amor! |

| João de Lobeira (1270?–1330?) |

The oldest written records of Galician-Portuguese are from the 9th century. In these official papers, parts of Galician-Portuguese appeared in texts written in Latin. This early stage is called "Proto-Portuguese." This is because the first documents came from the old County of Portugal, even though Portuguese and Galician were still one language. This period lasted until the 12th century.

The Age of Poetry

What scholars call Galician-Portuguese was the main language of the medieval Kingdom of Galicia. This kingdom was founded in 410 and included northern Portugal. It was also often used for lyric songs in other Christian kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula. Poets from places like Leon, Castile, Aragon, and Catalonia used it. It is also the language of the famous Cantigas de Santa Maria. These songs are usually linked to Alfonso X, a Castilian king. But newer studies show many translators, poets, and musicians worked together on them.

Portuguese Becomes Its Own Language

Portugal became an independent kingdom in 1143. This was recognized by the Kingdom of León, which Galicia was part of then. Afonso Henriques became Portugal's first king. In 1290, King Diniz started the first Portuguese university in Coimbra. He ordered that the language of the Portuguese, then called the "Vulgar language" (meaning everyday Vulgar Latin), should be used instead of Latin. He named it the "Portuguese language."

By 1296, Portuguese was used by the royal government. It was used not just for poetry but also for writing laws and official documents. In this first period of "Old Portuguese" (from the 12th to 14th century), the language was slowly used more in official papers.

As the County of Portugal separated from Galicia, Galician-Portuguese began to lose its unity. It slowly became two different languages. This difference grew faster when the kingdom of León joined with Castile (13th century). Galician was then more and more influenced by Castilian. Meanwhile, the southern version of Galician-Portuguese became the modern Portuguese language within the Kingdom of Portugal and its empire.

Portuguese Around the World

Portuguese is the second most spoken Romance language, after Spanish. This is partly because many people speak it in Brazil, where it is the national language. Brazilian Portuguese and European Portuguese have many differences in sounds and structure.

One clear difference is that Brazilian Portuguese has more vowels that you can hear clearly. Also, the way both languages are spoken keeps changing as generations grow older and the world becomes more connected. This leads to changes in how the language is used globally. Portuguese is also an official language in Mozambique, Angola, the Cape Verde Islands, Guinea-Bissau, Equatorial Guinea, Sao Tome and Principe, East Timor, and Macao.

Modern Portuguese and Its Growth

Standardizing the Language

The end of "Old Portuguese" was marked by the book Cancioneiro Geral by Garcia de Resende in 1516. "Modern Portuguese" developed from the early 16th century until today. During the Renaissance, scholars and writers borrowed many words from Classical Latin and ancient Greek. This made the Portuguese lexicon (all its words) more complex. Most educated Portuguese speakers also knew Latin. So, they easily added Latin words into their Portuguese writing and later into their speech.

Like most other European languages, Portuguese became more standardized because of the printing press. In 1536, Fernão de Oliveira published his Grammatica da lingoagem portuguesa in Lisbon. This was the first Portuguese grammar book. Soon after, in 1540, João de Barros published his Gramática da Língua Portuguesa. This book, with pictures, is thought to be the world's first printed illustrated textbook.

Spreading During the Age of Discovery

The second period of Old Portuguese was from the 14th to the 16th centuries. This time was marked by the Portuguese discoveries. Explorers, traders, and missionaries spread the Portuguese language to many parts of Africa, Asia, and The Americas. Today, most Portuguese speakers live in Brazil, which was Portugal's largest colony.

By the mid-16th century, Portuguese became a lingua franca (a common language used by people who speak different native languages) in Asia and Africa. It was used for government, trade, and talking between local officials and Europeans of all countries. In Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka), several kings spoke Portuguese well, and nobles often took Portuguese names. The language spread because it was linked to Catholic missionary efforts. This led to it being called Cristão ("Christian") in many places.

The Nippo Jisho, a Japanese–Portuguese dictionary written in 1603, was created by Jesuit missionaries in Japan. The language stayed popular in parts of Asia until the 19th century. This was true even though the Dutch tried hard to stop its use in Ceylon and Indonesia.

Some Portuguese-speaking Christian groups in India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Indonesia kept their language even after being cut off from Portugal. The language has changed a lot in these groups. It has become several Portuguese creoles (new languages formed from a mix of languages). Also, many Portuguese words are found in Tetum, the national language of East Timor. Examples include lee "to read" (from ler) and aprende "to learn" (from aprender).

Portuguese words also entered many other languages. For example, pan "bread" (from pão) in Japanese, sepatu "shoe" (from sapato) in Indonesian, and meza "table" (from mesa) in Swahili. Because the Portuguese Empire was so vast, many words also entered English. These include albino, baroque, mosquito, potato, savvy, and zebra.

How Portuguese Sounds Changed

In its word structure (morphology) and sentence structure (syntax), Portuguese is a natural change from Latin. No other language directly changed it. The sounds, grammar forms, and sentence types, with a few exceptions, come from Latin. Almost 80% of its words still come from the language of Rome. Some changes started during the Roman Empire, others happened later. A few words stayed almost the same, like carro (car) or taberna (tavern).

New words were added in the late Middle Ages because the Catholic Church used Church Latin. More words were added during the Renaissance, when Classical antiquity and Literary Latin were very respected. For example, the Latin word aurum, which became ouro (gold) and dourado (golden), was brought back as the adjective áureo (golden). In the same way, locālem (place), which became lugar, was later brought back as the more formal local. Many Greek and Latin words were also added or brought back this way. Because of this, many of these words are still familiar to Portuguese speakers.

Sounds in Old and Modern Portuguese

Old Portuguese (from the 11th to 16th centuries) had seven oral vowels and five nasal vowels. The sounds of vowels changed depending on whether they were stressed or not.

Around the 16th century, according to Fernão de Oliveira's grammar book, some vowels were already considered different sounds. Over time, Brazilian and European Portuguese started to develop separately. This led to important differences in how vowels are pronounced. For example, European Portuguese developed a ninth new vowel sound.

Palatalization

This is when certain consonant sounds like 'k' and 't' changed when next to 'e', 'i', or 'y' sounds.

- For example, Latin centum (hundred) became Old Portuguese cento and then Modern Portuguese cem.

- Latin facere (to do) became Old Portuguese fazer and then Modern Portuguese fazer.

Voicing

Some consonant sounds changed from being voiceless to voiced, or from voiced to voiced fricatives (a sound made by forcing air through a narrow gap).

- Latin mūtum (mute) became Old Portuguese mudo and then Modern Portuguese mudo.

- Latin lacum (lake) became Old Portuguese lago and then Modern Portuguese lago.

Lenition

This means consonant groups, especially double consonants, became simpler.

- Latin guttam (drop) became Old Portuguese gota and then Modern Portuguese gota.

- Latin quattuor (four) became Old Portuguese quatro and then Modern Portuguese quatro.

The 'b' sound often changed to a 'v' sound. This 'v' sound came either from a Latin 'b' between vowels or from the Latin letter 'v' (which sounded like 'w' in Classical Latin but later became a fricative).

Losing Sounds

Sometimes, 'l' and 'n' sounds in Vulgar Latin disappeared between vowels. Then, the vowels around them sometimes joined together, or a new vowel-like sound was added.

- Latin dolōrem (pain) became Old Portuguese door and then Modern Portuguese dor.

- Latin bonum (good) became Old Portuguese bõo and then Modern Portuguese bom.

Nasal Sounds

In medieval Galician-Portuguese, 'm' and 'n' between vowels or at the end of a syllable often became a nasal sound. This made the vowel before it sound nasal too. This change created one of the biggest sound differences between Portuguese and Spanish.

- Latin bonum (good) became Old Portuguese bõo and then Modern Portuguese bom.

- Latin manum (hand) became Old Portuguese mão and then Modern Portuguese mão.

Sometimes, nasal sounds spread forward from a nasal consonant.

- Latin mātrem (mother) became Old Portuguese mãy and then Modern Portuguese mãe.

Adding Sounds

Sometimes, a sound was added to break up a sequence of vowels.

- Latin arēnam (sand) became Old Portuguese arẽa and then Modern Portuguese areia.

- Latin gallīnam (chicken) became Old Portuguese galĩa and then Modern Portuguese galinha.

Dissimilation

This is when similar sounds became different over time because of nearby sounds.

- Latin locustam (lobster) became Old Portuguese lagosta and then Modern Portuguese lagosta.

- Latin memorāre (to remember) became Old Portuguese nembrar and then Modern Portuguese lembrar.

Metathesis

This is a sound change that swaps the order of sounds in a word.

- Latin prīmārium (primary) became Old Portuguese primeiro and then Modern Portuguese primeiro.

- Latin tenebrās (darkness) became Old Portuguese tẽevras and then Modern Portuguese trevas.

How Sounds Changed in Medieval Portuguese

Old Portuguese had seven sibilant sounds (hissing or buzzing sounds). These sounds changed over time. For example, the 'ch' sound in Old Portuguese eventually merged with the 'x' sound in most places.

| Old Portuguese | Modern Portuguese | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthography | Pronunciation | Orthography | Pronunciation |

| ⟨j⟩ or soft ⟨g⟩ | /dʒ/ → /ʒ/ | ⟨g⟩ before ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩; ⟨j⟩ elsewhere | /ʒ/ |

| ⟨g⟩ before ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩; ⟨j⟩ elsewhere | /ʒ/ | ||

| ⟨z⟩ | /d͡z̪/ → /z̪/ | ⟨z⟩ | /z̪/ |

| intervocalic ⟨s⟩ | /z̺/ | intervocalic ⟨s⟩ | |

| ⟨ch⟩ | /t͡ʃ/ | ⟨ch⟩ | /ʃ/ |

| ⟨x⟩ | /ʃ/ | ⟨x⟩ | |

| ⟨c⟩ before ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩; ⟨ç⟩ before ⟨a⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨u⟩ | /t͡s̪/ | ⟨c⟩ before ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩; ⟨ç⟩ or ⟨s⟩ before ⟨a⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨u⟩ | /s̪/ |

| ⟨s⟩ in syllable onset or coda; ⟨ss⟩ between vowels | /s̺/ | ⟨s⟩ in syllable onset or coda; ⟨ss⟩ between vowels | |

The 'v' sound was once pronounced differently in medieval times. Later, it changed to the 'v' sound we know today in central and southern Portugal and Brazil. In northern Portugal and Galicia, it merged with the 'b' sound.

In Portugal, the 'r' sound at the end of a syllable became a 'uvular fricative' (a sound made in the back of the throat). In most parts of Brazil, this 'r' sound became an unvoiced fricative (like the 'h' in 'hat').

The 'l' sound at the end of a syllable became 'velarized' (made with the back of the tongue raised) in Portuguese. This is still true in Portugal. But in Brazil, it changed even more and became like a 'w' sound.

See also

In Spanish: Historia del idioma portugués para niños

In Spanish: Historia del idioma portugués para niños

- Differences between Spanish and Portuguese

- Galician language

- History of Galicia

- History of Portugal

- History of Brazil

- List of English words of Portuguese origin

- Portuguese vocabulary

- Romance languages

- Spelling reforms of Portuguese

- Museum of the Portuguese Language

- Portuguese Language Orthographic Agreement of 1990

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |