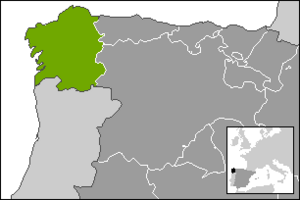

History of Galicia facts for kids

The Iberian Peninsula, where Galicia is located, has been home to people for at least 500,000 years. First, Neanderthals lived there, followed by modern humans. Around 4500 BC, a megalithic culture, known for building with huge stones, developed in Galicia and much of the northern and western parts of the peninsula. These people entered the Bronze Age around 1500 BC. They later became known as the Gallaeci, a group of Celtic tribes. The Roman Empire conquered them in the first and second centuries AD.

As the Roman Empire grew weaker, various Germanic tribes, like the Suebi and Visigoths, took control of Galicia until the 9th century. Then, the Muslim conquest of Iberia reached Galicia, but they never fully controlled the area.

In the 9th century, remains believed to be those of Saint James were found. Saint James was an apostle who brought Christianity to Spain in the first century. The Santiago de Compostela church was built to honor these holy remains. This church became one of the most important Christian pilgrimage sites in the world.

Wars, especially between Christians and Muslims, were common in Galicia during the Middle Ages. This period was known as the Reconquista, where Christians slowly took back land from Muslim kingdoms in Spain. This lasted until the 15th century. During this time, Galicia was sometimes an independent kingdom. Other times, it was part of or joined with kingdoms like Asturias, León, or Portugal. The country of Spain was formed at the end of the 15th century. This happened when the Crown of Castile (which Galicia was part of) and the Crown of Aragon united.

During the 19th century, people in Galicia felt more strongly about having their own separate identity from the rest of Spain. In the 1930s, the Second Spanish Republic allowed Galicia to have official self-government. However, after the Spanish Civil War, the government of Francisco Franco removed this self-rule. Franco's government tried to suppress local cultures across Spain, favoring a single Spanish identity. When Spain became a democracy again after Franco's death in 1975, Galicia regained its self-government. Since then, there have been many efforts to protect and celebrate Galician heritage and culture.

Contents

Ancient History of Galicia

Early Stone Age Builders

Galicia, northern Portugal, Asturias, and parts of León and Zamora formed a single area with a unique culture. This was during the Neolithic and Chalcolithic Ages, also called the Copper Age, from about 4500 to 1500 BC.

This was the first major culture in Galicia. These people were skilled builders and had a strong sense of religion. They believed in honoring the dead, seeing them as links between humans and gods.

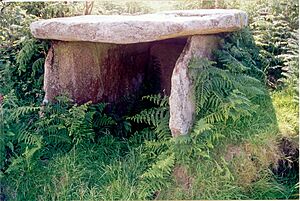

Thousands of ancient tombs called dolmens (or mámoas) remain from this time. These are found all over the region. Their social structure was likely based on clans, which are groups of families.

Bronze Age Discoveries

The arrival of bronze-working techniques brought a new cultural period. Metals became very important, leading to a lot of mining activity.

People from the Castilian plateau moved to Galicia, increasing the population. Galicia's location near the Atlantic Ocean gave it a very humid climate.

More people meant some conflicts, but also more mining and production. They made weapons, useful tools, and beautiful gold and bronze ornaments. Jewelry made from Galician metals was traded across the Iberian Peninsula and other parts of Europe.

Ancient Times

The Gallaeci: Celtic People of Galicia

At the end of the Iron Age, people in northwestern Iberian Peninsula shared a similar culture. Early Greek and Latin writers called them "Gallaeci" (Galicians). This name might have come from their similarity to the Galli (Gauls). The name Galicia comes from this group of tribes.

The Gallaeci were originally a Celtic people. For centuries, they lived in the area of modern Galicia and northern Portugal. To the south were the Lusitanians, and to the east were the Astures. The Gallaecians lived in fortified villages called castros (Latin: castra). These were hillforts, ranging from small villages to large ones over 10 hectares.

Living in hillforts was common in Europe during the Bronze and Iron Ages. In northwestern Iberia, this was called the "culture of hillforts" or "Castro Culture". This way of life existed before the Roman Empire arrived. Even after the Romans left, Gallaeci-Romans continued to live in hillforts until the 8th century AD. In modern Galicia alone, there are over two thousand hillforts. This shows how spread out the population was during the Iron Age in Europe. This pattern of small, numerous, and distant settlements is still seen in Galicia today.

The Gallaeci were organized into small, independent states. Each state had many hillforts and was led by a local king called a princeps by the Romans. Each Gallaecian identified with their hillfort and the larger group (Populus) it belonged to. Many tribes existed among the Gallaeci, such as the Artabri and Bracari.

In terms of religion, the Gallaeci had a Celtic faith. They worshipped gods like Bormanus, Coventina, and Lugus.

Roman Rule in Gallaecia (19 BC – 410 AD)

We don't know much about the hillfort societies from Roman historians. They described Galicians as barbarians who fought all day and partied all night. However, it seems that in the last five centuries BC, they developed a society with different social classes. The Romans were mainly interested in this region because of its gold mines.

When Iberia was involved in the Punic Wars between the Carthaginians and Romans, Hannibal recruited many Gallegans. When the Romans began conquering Iberia, the Gallaicoi fought them in 137 BC. The Romans won a big victory against 60,000 Galicians at the Douro river. The Roman general, Decimus Iunius Brutus, returned to Rome as a hero and was given the name Gallaicus.

After Brutus's campaigns, Rome controlled the land between the Douro and Minho rivers. The second invasion in 61 BC, led by Julius Caesar, landed at Brigantium (A Coruña).

It seems that the Celtic resistance against the Romans ended here. From then on, many Galicians joined the Roman legions as helpers. They were sent to places far from Galicia, like Thrace and Dacia. More than a third of all Roman helper troops from Iberia came from the northwestern tribes.

The final end of Celtic resistance was the goal of the fierce Cantabrian Wars. These wars were fought under Emperor Octavian from 26 to 19 BC. The resistance was strong, with people preferring to die rather than surrender.

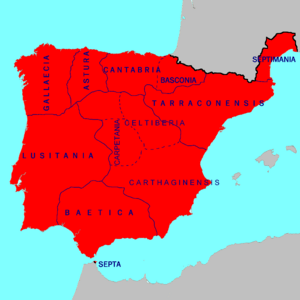

In the 3rd century, Emperor Diocletian created a new administrative area. This included Gallaecia, Asturica, and possibly Cluniense. This province was named Gallaecia because it was the most populated and important part. In 409 AD, as Roman control weakened, the Suebi conquered Roman Gallaecia. This turned it into the kingdom of Gallaecia.

Medieval Galicia

The Suebic Kingdom (410–585)

In 411 AD, Galicia came under the rule of the Suebi, who formed their own kingdom.

Historians believe fewer than 30,000 Suebic invaders arrived. They settled mainly in cities like Braga (Bracara Augusta), Porto, Lugo (Lucus Augusta), and Astorga (Asturica Augusta). Braga became the capital of the Suebi, just as it had been the capital of the Roman province of Gallaecia. Suebic Gallaecia was larger than modern Galicia. It stretched south to the Douro river and east to Ávila.

The Suebic kingdom in Gallaecia lasted from 410 to 584 AD. It seemed to have a fairly stable government for most of that time. Historians believe that Galician culture was shaped by a mix of Roman culture and Suebic traditions.

There were occasional fights with the Visigoths. The Visigoths arrived in the Iberian Peninsula in 416 AD and eventually controlled most of it. However, the Suebi kept their independence until 584 AD. That year, the Visigothic King Leovigild invaded the Suebic kingdom and defeated it, bringing it under Visigoth control.

Galicia remained connected to the wider Roman and Mediterranean world even in later ancient times. For example, the Galician nun Egeria traveled to the Holy Land between 381 and 384 AD. Also, King Miro of the Suevi had diplomatic ties with other barbarian kings and even with the emperors in Constantinople.

Britons Arrive and Settle

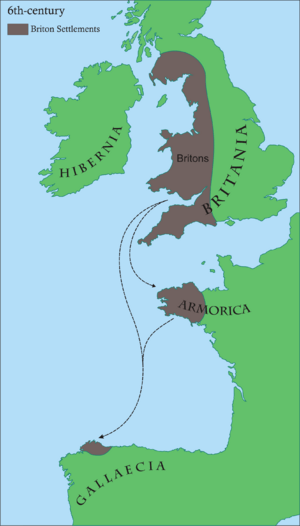

Between the 4th and 7th centuries, the situation in Britain changed a lot. Rome left the island, and Anglo-Saxon tribes from northern Germany and Denmark constantly attacked the eastern part of Great Britain. Because of these attacks, some native Britons sailed away to other Atlantic coastal areas. They settled in what is now northwest France (known as Brittany) and in the north of ancient Gallaecia.

We don't know exactly why some Britons moved to the north coast of Galicia or how the Galician-Suevi people welcomed them. Some historians think there might have been a military agreement, or perhaps the local people simply accepted them.

These Britons organized themselves in an important territory. They brought their own Christian religious system, which was a bit different. They founded their own bishopric, which is mentioned in a document from 572-573 AD. This document describes the church organization of the kingdom of Galicia during the Suevic monarchy. Their religious integration was complete, as their representative, Maeloc, attended an important church council in Braga in 572.

The ancient area of the Britonia diocese covered mostly the coastal strip from Lugo's coast to the Terra Chá. Its influence reached the Eo-Navia region to the east and western Ferrol. The original main church, known as Maximus Monastery, is thought by some to be the medieval Basilica of Saint Martin of Mondoñedo, where remains from the 5th-6th centuries have been found. The name and location of this diocese changed several times. Today, the Galician diocese of Mondoñedo is its historical successor.

The settlement of these British immigrants and the creation of their Christian diocese was the second largest settlement of a foreign people in Galicia, after the Suebi.

Visigothic Kingdom (585 – 711)

As the Visigothic kings became Catholic, the power of Catholic bishops grew. At a church meeting in Toledo in 633, bishops gained the right to choose a king from the royal family.

Rodrigo, the last elected king, was betrayed by Julian, count of Ceuta. Julian asked the Umayyad Muslims (also called Moors) to enter Hispania. During the battle of Guadalete in 711, King Rodrigo died. Part of his army turned against him, led by Bishop Oppas, who worked with the Moors. The entire kingdom fell, and the throne was left empty. One of the few survivors was Pelayo, a noble in charge of the royal guard.

The Kingdom of Asturias and Moorish Iberia

This marked the start of the Umayyad conquest of Hispania. Most of the peninsula came under Islamic rule by 718. This quick conquest can be seen as a continuation of civil wars that had affected the peninsula for centuries. Also, a large part of the population converted to Islam.

Pelayo is known for starting the Christian Reconquista of Iberia in 718 or 722. He defeated the Umayyads in the Battle of Covadonga and established the Kingdom of Asturias in the northern part of the peninsula.

Although the lands of the former Kingdom of Gallaecia were invaded by the Moors, there is no clear proof that any invasion force ever crossed beyond the Galician mountains into Galicia itself. They only went as far as occupying Asturica (modern León) and Gijón (modern Asturias). There is no evidence of any Moorish occupation of any settlement in modern Galicia. So, it's just a guess to assume the region was ever conquered or even invaded by the Moors.

After being briefly occupied by the Moors, Asturias revolted in 718 or 722. Led by Pelayo, they formed the Kingdom of Asturias. Later, in 736, Alfonso I of Asturias brought Galicia under his Kingdom of Asturias. This lasted until 924, when it became the Kingdom of León.

During the early Reconquista, Galicia expanded south. It established the County of Portugal in 868 and the County of Coimbra in 878.

The Discovery of Saint James's Tomb (813)

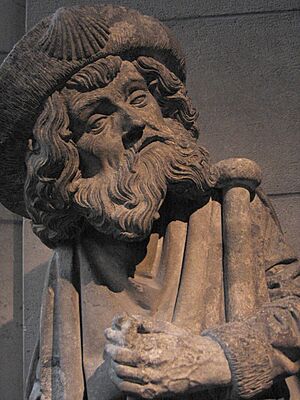

In 813, a chest was found in Galicia containing remains believed to belong to the apostle Saint James. According to Christian stories, Pelagius the Hermit saw a star over a marble chest near Libredón. Pelagius told Theodemir, the bishop of Iria Flavia, who quickly went to the spot. He identified the remains as the body of Apostle James.

Whether true or a legend, this "discovery" was quickly promoted by the Galician-Asturian king, Alphonse II (791–842). In the same year, he ordered a church to be built around the tomb and spread the news across the Christian world. Iria Flavia became a very powerful church center, not just in medieval Gallaecia but across the entire Iberian Peninsula. Its power grew with constant gifts from the king to the church of Santiago de Compostela. It became the third most important pilgrimage site in Christianity, after Jerusalem and Rome. From the 11th and 12th centuries, pilgrims from many parts of Europe began to arrive. They came from places like Occitania, France, Navarra, Aragon, and Catalonia (by land). Others came from the British Isles, Scandinavia, and German areas (by sea).

The pilgrimage was very important in shaping the culture and economy of the Kingdom of Galicia. This development happened especially during Bishop Diego Gelmirez's time (1100–1136). He successfully made Compostela a metropolitan church in 1122. This was the most important Christian position in Western Christianity after Rome. Around the Apostle's tomb, not only a cathedral grew, which was a great center of art and religion, but also a village and then a town. This town became very strong in the Middle Ages, with trade linked to its status as a holy city. The city of Compostela was where Galician kings were crowned. It was also where the great Galician-Portuguese lyric school developed. Since the Middle Ages, it has been the capital of Galicia.

However, historical and archaeological studies of the cathedral in the 20th century showed something interesting. During Roman and even Suevic times, Compostela was an important place where important people had been buried long before 813. Some experts believe that the body thought to be Saint James was actually the body of Priscillian. Priscillian was a church leader in Galicia.

The Reconquista and Changing Kingdoms

During the 9th and 10th centuries, the counts of Galicia sometimes obeyed their king and sometimes did not. Normans and Vikings occasionally raided the coasts. The Towers of Catoira in Pontevedra were built to stop Viking raids on Santiago de Compostela.

Constant rivalry between the Kingdom of León and the Kingdom of Castile created weaknesses. Sancho III "the Great" of Navarre (1004–1035) took over Castile in the 1020s. He added León in the last year of his life, leaving Galicia temporarily independent. After his death, his son Fernando received the county of Castile. Two years later, in 1037, Fernando conquered León and Galicia. In 1065, Ferdinand I of Castile and León divided his kingdom among his sons. Galicia was given to Garcia II of Galicia.

Kingdom of Galicia and Portugal

The Kingdom of Galicia and Portugal was formed in 1065. This happened after the County of Portugal declared independence when Ferdinand I of León died. The Count of Portugal, Nuno Mendes, used the internal conflicts among Ferdinand's sons to break away and become an independent ruler. However, in 1071, King Garcia II defeated and killed him at the Battle of Pedroso. Garcia then took over Portugal, adding the title of King of Portugal to his others. In 1072, King Garcia II was defeated by his brother Sancho II of Castile and fled. In the same year, after Sancho was murdered, Alfonso VI became king of Castile and León. He imprisoned Garcia for life and also declared himself King of Galicia and Portugal. This reunited his father's kingdom. From that time, Galicia remained part of the kingdom of Castile and León, though with different levels of self-government.

In 1095, Portugal separated almost completely from the Kingdom of Galicia. Both were under the rule of the Kingdom of León, just like Castile. Portugal's lands were mostly mountains, moorland, and forests. They were bordered by the Minho river to the north and the Mondego to the south.

Saint James and Galicia

The story of Saint James's remains being brought to Galicia is full of miraculous events. Legend says he was killed in Jerusalem by Herod Agrippa. His body was then carried by angels in a boat without a rudder or crew to Iria Flavia in Spain. There, a huge rock closed around his remains at Compostela. The Historia Compostellana tells the legend of Saint James as it was believed in Compostela in the 12th century. Two main ideas are central to it: first, that Saint James preached the gospel in Spain and the Holy Land; second, that after his death, his followers carried his body by sea to Spain. They landed at Padrón on the coast of Galicia and took it inland for burial at Compostela.

An even later tradition says that he miraculously appeared to fight for the Christian army during the Battle of Clavijo during the Reconquista. From then on, he was called Matamoros (Moor-slayer). Santiago y cierra España ("St James and strike for Spain") has been the traditional battle cry of Spanish armies.

- St. James the Moorslayer, one of the most valiant saints and knights the world ever had ... has been given by God to Spain for its patron and protection.

— Cervantes, Don Quixote.

It's also possible that the worship of Saint James was started to replace the Galician worship of Priscillian. Priscillian was executed in 385 AD and was widely honored across northern Spain as a martyr.

Modern Galicia

Emigration: Leaving Home

In the 1850s, Galicia experienced unusually cold winters and many families relied on small farms. This led to many farms going bankrupt.

The weather during this decade was sometimes compared to a mini Ice Age. In January 1850, there was a lot of snow across Spain. By February, many wolves roamed the countryside. In February 1853, the Galician port cities of Ferrol and A Coruña reported heavy snowfall, which was very unusual. February 1854 was also very cold. In January 1855, northern Spain was again very cold and snowy.

The winter of 1856–57 was especially harsh.

Official reports in the Spanish government's newspaper, La Gaceta de Madrid, highlighted how cold the winter was. From Puigcerda (Girona), it was reported that "For more than a month the countryside has been snow-covered." From Biscay, "As a consequence of the copious snows that have fallen over our region during the past days, especially on the peaks of the Valley of Carranza, there has appeared down in the valley a strong pack of wolves that is inflicting great losses on herds of sheep and cattle." Many announcements were made about plans to hunt wolves during those cold days of 1857. The snow fell over all of northern Spain from Galicia to Catalonia. On February 4, the province of Santander had been cut off from the interior for three months due to snow. "No one remembers such a prolonged spell of bad weather."

To make things worse, the main local industry also faced problems.

From the second half of the 19th century, Galicia's textile industry suffered a serious crisis. This was caused by legal imports and smuggled foreign fabrics. Many families struggled because there were no other jobs. To make matters worse, the farming sector faced a crisis between 1850 and 1860, which hurt the rural economy. This combination of problems forced people to look for a better life overseas.

The economic problems sped up the existing emigration.

There is evidence of many people leaving Galicia between 1810 and 1853. It's hard to count them because the Spanish government didn't officially allow emigration. So, some writers call this time the period of secret emigration.

But from 1836, Spain started to officially recognize its newly independent former colonies. Mexico was the first former colony recognized in 1836, and Uruguay, Chile, and Argentina followed soon after. As a result, emigration increased. In December 1836, the first advertisement appeared offering trips across the Atlantic. It was for the ship General Laborde from A Coruña to Montevideo, Buenos Aires, and other places in Mar del Plata. More and more transatlantic trips were offered. Most trips were on sailing ships. In 1850, the ship Juan left from Carril, advertised as a first-class steamer. Reliable data suggests that 93,040 Galicians left between 1836 and 1860.

The Spanish government made emigration legal in 1853. This made counting easier: 122,875 people left Galicia between 1860 and 1880.

The census of 1857 found 1,776,879 people in the region. So, according to these numbers, over 12% of the population left Galicia between 1836 and 1880.

Emigration continued well into the 20th century. The famous Galician writer and politician Alfonso Castelao (1886–1950) himself lived abroad twice. He saw emigration as both an economic need and a sign of a brave spirit. However, leaving one's homeland was often difficult for most people, whether in the 19th or 20th century, as shown in Manuel Ferrol's photographs.

Contemporary Galicia

Galician nationalist and federalist movements began in the 19th century. After the Second Spanish Republic was declared in 1931, Galicia became a self-governing region after a public vote.

After the Spanish Civil War and the establishment of the Spanish State, Galicia's self-government was cancelled. The government of Francoist Spain also stopped any official promotion of the Galician language. However, people still used it every day. During the last ten years of Franco's rule, nationalist feelings in Galicia grew stronger again.

After Franco's death in 1975, Spain became a democracy. Galicia then regained its status as a self-governing region within Spain. Different levels of nationalist or separatist feelings are seen in politics. The main nationalist party, the Bloque Nacionalista Galego or BNG, wants more self-rule from the Spanish state. They also want to protect Galician heritage and culture. Other groups want complete independence from Spain. Some smaller groups hope to join with Portugal and the Portuguese-speaking world. However, nationalist parties have only received a minority of votes in elections so far.

From 1990 to 2005, the region's government, the Xunta de Galicia, was led by the Partido Popular ('People's Party'). This is Spain's main national conservative party, led by Manuel Fraga. He was a former minister and ambassador in the Francoist government. However, in the 2005 Galician elections, the People's Party lost its overall majority. It remained the largest party in the parliament.

As a result, power went to a coalition government. This was formed by the Partido Socialista de Galicia (PSdeG) ('Galician Socialist Party') and the BNG. The PSdeG is a regional partner of Spain's main socialist party. As the main partner in the new coalition, the PSdeG chose its leader, Emilio Perez Touriño, to be Galicia's new president.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Galicia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Galicia para niños

- Timeline of Galician history

- Suebi

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |