Battle of Ramillies facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Ramillies |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Spanish Succession | |||||||

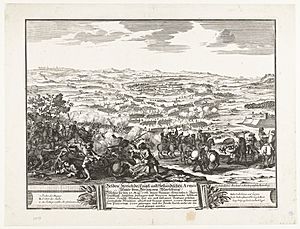

The Battle of Ramillies by Jan van Huchtenburg |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 62,000 | 60,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3,663-5,000 | 13,000-15,000 | ||||||

The Battle of Ramillies was a major battle fought on May 23, 1706. It was a key part of the War of the Spanish Succession. This war was fought to decide who would rule Spain and its vast empire. On one side was the Grand Alliance, which included England, the Dutch Republic, and Austria. On the other side were the armies of King Louis XIV of France and his allies, like Bavaria and Spain.

In 1705, the Grand Alliance had a tough year. They had some wins, like capturing Barcelona, but also faced setbacks. King Louis XIV of France wanted peace, but on his own terms. To keep up their strength, the French and their allies decided to attack in 1706.

The year started well for France. Their generals won battles in Italy and along the Rhine River. Encouraged by this, King Louis XIV told his general, Marshal Villeroi, to attack in the Spanish Netherlands. Villeroi led about 60,000 men from Leuven. The Grand Alliance commander, the Duke of Marlborough, gathered his army of about 62,000 men near Maastricht. Both armies were looking for a fight. They met on dry ground between the Mehaigne and Petite Gette rivers, near the small village of Ramillies.

In less than four hours, Marlborough's forces, including Dutch, English, and Danish troops, completely defeated Villeroi's French, Spanish, and Bavarian army. Marlborough used clever moves that Villeroi didn't notice until it was too late. This trapped the French army. After their victory, the Allies quickly captured many towns, including Brussels, Bruges, and Antwerp. By the end of the campaign, Villeroi's army was pushed out of most of the Spanish Netherlands. This victory, along with another Allied win in Italy, caused King Louis XIV to lose a lot of land and resources during the war. The year 1706 was a truly amazing year for the Grand Alliance.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

After a big defeat at Blenheim in 1704, the French got a bit of a break in 1705. The Duke of Marlborough had planned to invade France through the Moselle valley in 1705. He hoped this would make King Louis XIV agree to peace. But his plan didn't work out. His Dutch allies didn't want to send too many troops away from their own borders. Also, a key German commander, the Margrave of Baden, couldn't join Marlborough with enough soldiers because he was ill.

The French King and his generals also caused problems for Marlborough. Marshal Villeroi put a lot of pressure on the Dutch forces along the Meuse River. He captured Huy and moved towards Liège. With another French general, Villars, holding strong on the Moselle, Marlborough had to stop his campaign in June. Villeroi was very happy, saying Marlborough had made "false movements without any result!"

Even though the Moselle campaign failed, the Anglo-Dutch forces had some small wins. They won at Elixheim and crossed the Lines of Brabant in the Spanish Netherlands. Huy was also recaptured. But Marlborough couldn't get the French into a big, decisive battle. The year 1705 was mostly disappointing for him. He spent time trying to get more support for the Grand Alliance from other European courts.

Getting Ready for Battle

Marlborough returned to London in January 1706, already planning his next moves. One idea was to move his army from the Spanish Netherlands to northern Italy. There, he would join Prince Eugene to defeat the French and protect Savoy. This would open a path into France. Another idea was to return to the Moselle valley and try to advance into France again.

However, these plans changed quickly. In April, news arrived of big setbacks for the Allies in other parts of the war. In Italy, a French general defeated the Imperial army, getting ready to besiege Turin. In Alsace, Marshal Villars surprised another Allied commander and pushed him back across the Rhine. Because of these losses, the Dutch refused to let Marlborough move his army far from their borders. So, Marlborough prepared to fight in the Low Countries.

Moving Towards the Fight

Marlborough left The Hague on May 9. He wrote to a friend, saying he had "no hope of doing anything considerable, unless the French do what I am very confident they will not..." He meant he didn't think the French would risk a big battle. On May 17, he gathered his Dutch and English troops near Maastricht. Some other allied troops, like the Hanoverians and Danes, were delayed. Marlborough asked the Danish commander to hurry his cavalry. He didn't think the French would leave their strong positions to attack.

But Marlborough was wrong. King Louis XIV wanted peace, but only if he could win a big victory first. He wanted to show the Allies that France was still strong. Louis XIV pushed his general, Villeroi, to attack. Villeroi felt the King doubted his courage, so he decided to risk everything. On May 18, Villeroi left Leuven with about 60,000 troops and marched to find the enemy. He was confident he could outsmart Marlborough.

Neither side expected to fight exactly where and when they did. The French first moved towards Tienen, then turned south towards Jodoigne. This path led Villeroi's army to the dry ground between the Mehaigne and Petite Gette rivers, near Ramillies. Villeroi thought the Allies were still a day's march away. Marlborough also thought Villeroi was further away than he was.

The next day, at 1:00 AM, Marlborough sent his Quartermaster-General, Cadogan, ahead to scout the area. Marlborough knew this land from past campaigns. Two hours later, Marlborough followed with his main army of 62,000 troops. Around 8:00 AM, Cadogan's scouts met some French soldiers. After a short fight, the French retreated. Cadogan then saw the French army lining up for battle about 6 kilometers away. He quickly sent a messenger to warn Marlborough. Two hours later, Marlborough saw the French army spreading out along a 6-kilometer front. He later said the French army "looked the best of any he had ever seen."

The Battle Begins

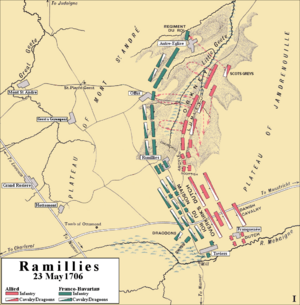

The Battlefield

The battlefield at Ramillies was wide open, like Blenheim. It had lots of farmland with no woods or hedges. Villeroi's right side was anchored by the villages of Franquenée and Taviers, with the Mehaigne river protecting his flank. A large open plain, about 2 kilometers wide, lay between Taviers and Ramillies. Villeroi's center was protected by Ramillies village itself, which was on a small hill. His left flank was protected by rough ground and a stream called the Petite Gheete. On the French side of the stream, the ground rose to Offus, which, along with Autre-Eglise further north, held Villeroi's left flank.

Setting Up the Armies

At 11:00 AM, Marlborough ordered his army into battle lines. On the far right, the British troops took their positions. In the center, about 30,000 Dutch, German, and Scottish infantry faced Offus and Ramillies. Marlborough also placed a powerful battery of thirty 24-pound cannons near Ramillies. These guns were pulled into place by oxen. More cannons were set up overlooking the Petite Gheete. On the left, on the wide plain between Taviers and Ramillies, the Dutch and Danish cavalry, supported by Dutch infantry and two cannons, took their places. Marlborough believed this open plain would be where the main fight happened.

Villeroi also set up his forces. On his right, in Taviers, he placed two battalions of Swiss soldiers. This position was protected by the swampy ground of the Mehaigne river. In the open plain between Taviers and Ramillies, he placed 82 cavalry squadrons. These were supported by French, Swiss, and Bavarian infantry. Along the Ramillies–Offus–Autre Eglise ridge, Villeroi placed Walloon and Bavarian infantry. The Elector of Bavaria's 50 squadrons of cavalry were behind them. Ramillies, Offus, and Autre-Eglise were filled with troops and prepared for defense. Villeroi also placed strong cannons near Ramillies. These guns could fire well across the plain where the Allied infantry would advance.

Marlborough noticed some weaknesses in the French setup. Villeroi had spread his forces too thin by trying to hold Taviers on his right and Autre-Eglise on his left. This also meant Marlborough could form a tighter line, making his attack more powerful. Marlborough could also move his troops across his front more easily than the French. This would become very important later. Villeroi seemed to be planning a defensive battle, which Marlborough correctly guessed.

Fighting at Taviers

At 1:00 PM, the cannons started firing. Soon after, two Allied groups attacked the sides of the French army. To the south, four battalions attacked the small village of Franquenée. The Swiss soldiers there were surprised and quickly pushed back towards Taviers. Taviers was very important for the French. It protected their cavalry on the open plain and allowed their infantry to threaten the Dutch and Danish cavalry.

The Dutch Guards then attacked Taviers. The fighting in the narrow streets and houses was fierce, with bayonets and clubs. But the Dutch had more firepower. By about 3:00 PM, the Swiss were pushed out of the village into the nearby marshes.

Villeroi's right side was now in trouble. He ordered 14 squadrons of French dragoons to attack. Two more Swiss battalions were also sent. But the attack was not well organized. The Anglo-Dutch commanders sent dismounted Dutch dragoons into Taviers. They, along with the Guards, fired heavily into the advancing French troops. A French officer leading his regiment was killed.

As the French lines wavered, the Danish cavalry, now free from enemy fire, charged the exposed French and Swiss infantry and dragoons. A French officer, de la Colonie, was ordered to support the counter-attack. But when he arrived, everything was chaotic. His own soldiers turned and fled. De La Colonie managed to gather some of his grenadiers, but it was a small force and offered little help to Villeroi's right flank.

Attacks on Offus and Autre-Eglise

While the attack on Taviers was happening, the Earl of Orkney led his English troops across the Petite Gheete stream. They attacked the fortified villages of Offus and Autre-Eglise on the Allied right. Villeroi watched the English advance carefully. He remembered King Louis XIV's advice to pay special attention to the part of the line that would face the English first. So, Villeroi began moving battalions from his center to strengthen his left flank. He also took more infantry from his already weak right side to replace them.

As the English troops went down the slope of the Petite Gheete valley and struggled through the swampy stream, they were met by disciplined Walloon infantry. The Walloons fired many volleys, causing heavy losses for the English. The English took some time to regroup on the dry ground and then pushed up the slope towards the houses and barricades on the ridge. The English attack was so strong that they threatened to break through the villages and onto the open plateau beyond. This was dangerous for the Allied infantry, who would then be open to attack from the Elector's cavalry waiting on the plateau.

Marlborough realized that he couldn't win the battle on his right flank. He saw that there wasn't enough cavalry support possible there. So, he called off the attack against Offus and Autre-Eglise. He sent his Quartermaster-General to make sure Orkney obeyed the order to pull back. Orkney protested, but he eventually ordered his troops to return to their original positions. Historians believe Marlborough might have intended this attack as a feint, or a trick, all along. It worked because Villeroi focused his attention and sent many troops to this wing. These troops should have been fighting in the main battle south of Ramillies.

The Fight for Ramillies

Meanwhile, the Dutch attack on Ramillies was getting stronger. Marlborough's younger brother, General Charles Churchill, ordered four brigades of infantry to attack the village. These included Dutch, Saxon, Scottish, and Swiss troops. The 20 French and Bavarian battalions in Ramillies, supported by Irish soldiers, fought hard. They initially pushed back the attackers, causing heavy losses.

Seeing that his troops were struggling, Marlborough ordered Orkney's second-line British and Danish battalions to move south towards Ramillies. These troops had not been used in the attack on Offus and Autre-Eglise. They moved behind a small hill, so the French couldn't see them. Their commander ordered their flags to be left behind to make the French think they were still in their original position. This meant the French didn't know that Marlborough was now putting all his strength against Ramillies and the open plain to the south. Villeroi, meanwhile, was still moving more infantry reserves to his left flank, away from the main fight. He didn't realize Marlborough's clever change in plans until it was too late.

Around 3:30 PM, Overkirk advanced his large cavalry force on the open plain to support the infantry attack on Ramillies. 48 Dutch squadrons, supported by 21 Danish squadrons, moved steadily towards the enemy. They started at a walk, then broke into a trot to gain speed for their charge. A French officer described how they advanced in four lines, then merged into one solid front, making it hard for the French cavalry to outflank them.

At first, the Dutch and Danish cavalry had the advantage. Villeroi had weakened his own cavalry by taking away infantry support to reinforce his left flank. Overkirk's cavalry pushed the first line of French horsemen back. This also put pressure on their second line, forcing them back to their third line and the few infantry battalions left on the plain. But these French horsemen were among the best in King Louis XIV's army. They were led by de Guiscard and fought back hard, pushing the Allied squadrons back in some areas.

On Overkirk's right, near Ramillies, ten of his squadrons suddenly broke ranks and fled. This left the left side of the Allied attack on Ramillies dangerously open. De Guiscard tried to use this chance to split the Allied army in two.

A crisis was building in the center. But Marlborough, from his high position, immediately saw the danger. He quickly ordered cavalry from his right wing to reinforce the center. He left only the English cavalry to support Orkney. Because of battle smoke and the terrain, Villeroi didn't notice this troop movement. He still had 50 unused cavalry squadrons that he didn't move. While waiting for the reinforcements, Marlborough himself rode into the fight, rallying some confused Dutch cavalry.

But his personal involvement almost led to disaster. Some French horsemen recognized the Duke and charged towards him. Marlborough's horse fell, and he was thrown off. An eyewitness said, "Major-General Murray... seeing him fall, marched up in all haste with two Swiss battalions to save him." Luckily, Marlborough's aide, Richard Molesworth, quickly helped him onto his own horse, and they escaped. Murray's soldiers then pushed back the French.

After a short break, another of Marlborough's horses was brought. But as he was getting on, his equerry, Colonel Bringfield, was hit by a cannonball and killed. The danger passed, and Overkirk and Tilly restored order among the cavalry. Marlborough continued to direct the cavalry reinforcements moving from his right flank, and Villeroi still didn't realize what was happening.

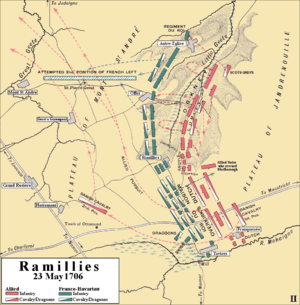

The Breakthrough

It was about 4:30 PM. The two armies were fighting along the entire 6-kilometer front. There was skirmishing in the southern marshes, a huge cavalry battle on the open plain, fierce fighting for Ramillies in the center, and Orkney and de la Guiche facing each other across the Petite Gheete in the north.

The arrival of Marlborough's transferred cavalry began to turn the tide for the Allies. The French cavalry, tired and suffering losses, were now outnumbered. After failing to hold Taviers, de Guiscard's right flank was dangerously exposed, and a gap opened in their line. The Danish cavalry swept forward, turning to attack the flank of the French elite cavalry, who were focused on holding back the Dutch. The 21 Danish squadrons reformed behind the French, facing north towards the exposed side of Villeroi's army.

The last Allied cavalry reinforcements were now in position. Marlborough's advantage on the left was clear, and his fast-moving plan was taking over the battlefield. Too late, Villeroi tried to move his 50 unused squadrons. But his attempt to form a line facing south failed because of the baggage and tents left carelessly in the French camp. Marlborough ordered his cavalry forward against the now heavily outnumbered French and Bavarian horsemen. De Guiscard's right flank, without proper infantry support, could no longer resist. They broke and fled in complete disorder. Even the squadrons Villeroi was trying to gather behind Ramillies couldn't stop the attack. An Irish captain serving with the French remembered, "the words sauve qui peut (save himself who can) went through the great part... and put all to confusion."

In Ramillies, the Allied infantry, now stronger with the English troops brought from the north, finally broke through. The French Régiment de Picardie fought hard but were caught between the Scottish-Dutch regiment and the English reinforcements. Many officers were killed. The Marquis de Maffei tried one last stand with his Bavarian and Cologne Guards, but it was useless. He saw horsemen approaching from the south and realized he was surrounded.

The Chase

The roads leading north and west were jammed with fleeing soldiers. Orkney sent his English troops back across the Petite Gheete stream to storm Offus again. The French infantry there had started to scatter. To the right of the infantry, the 'Scots Greys' cavalry also crossed the stream and charged a French regiment in Autre-Eglise. One soldier wrote that their dragoons "made terrible slaughter of the enemy." The Bavarian cavalry and guards tried to protect Villeroi and the Elector, but they were scattered by Allied cavalry. Villeroi and the Elector barely escaped capture by an Allied general who didn't recognize them. Far to the south, the remaining French troops headed towards the French fortress of Namur.

The retreat turned into a complete rout. Allied commanders pushed their troops forward, giving the defeated enemy no chance to recover. Soon, the Allied infantry couldn't keep up, but their cavalry chased the French through the night towards the Dyle river crossings. Marlborough finally called a halt to the chase shortly after midnight, about 12 miles from the battlefield. Captain Drake wrote, "It was indeed a truly shocking sight to see the miserable remains of this mighty army... reduced to a handful."

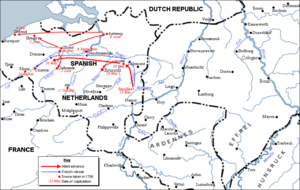

What Happened Next

What was left of Villeroi's army was completely broken. The huge difference in casualties shows how bad the defeat was for King Louis XIV's army. Hundreds of French soldiers became fugitives, meaning they ran away and never rejoined their units. Villeroi also lost 52 cannons and all his bridge-building equipment. Marshal Villars called the French defeat at Ramillies "the most shameful, humiliating and disastrous of routs."

Town after town quickly fell to the Allies. Leuven fell on May 25, 1706. Three days later, the Allies entered Brussels, the capital of the Spanish Netherlands. Marlborough saw the huge opportunity this victory created. He wrote, "We now have the whole summer before us... and with the blessing of God I shall make the best use of it." Many other towns, including Malines, Lierre, Ghent, Alost, Damme, Oudenaarde, Bruges, and Antwerp, also fell to Marlborough's army. Like Brussels, they all declared the Austrian candidate, the Archduke Charles, as their new ruler. Villeroi couldn't stop this collapse. When King Louis XIV heard about the disaster, he called Marshal Vendôme from northern Italy to take command in Flanders.

As news of the Allied victory spread, the Prussian, Hessian, and Hanoverian troops, who had been delayed, eagerly joined the chase of the broken French and Bavarian forces. Marlborough wrote that this was "owing to our late success." Meanwhile, Overkirk captured the port of Ostend on July 4. This opened a direct route to the English Channel for supplies and communication.

Vendôme officially took command in Flanders on August 4. Villeroi never received another major command. King Louis XIV was kind to his old friend, saying, "At our age, Marshal, we must no longer expect good fortune." Marlborough then besieged the strong fortress of Menin, which fell on August 22 after a costly siege. Dendermonde finally surrendered on September 6, followed by Ath on October 2. By the end of the Ramillies campaign, Marlborough had taken most of the Spanish Netherlands from the French. It was a huge victory for the English Duke, but it didn't completely defeat France.

The Allies then had to decide what to do with the Spanish Netherlands. Austria and the Dutch had different ideas. Emperor Joseph I wanted his brother, King Charles III, to immediately rule the recaptured areas. But the Dutch, who had provided most of the troops and money for the victory, wanted to control the region until the war ended. They also wanted to keep strong forts there after the peace. Marlborough tried to mediate between them, favoring the Dutch position. The Emperor even offered Marlborough control of the Spanish Netherlands, but Marlborough refused for the sake of Allied unity. In the end, England and the Dutch Republic controlled the new territory during the war. After the war, it would go to Charles III, with the Dutch keeping some forts.

Meanwhile, on the Upper Rhine, the French general Villars had to go on the defensive. Many of his battalions were sent north to help the collapsing French forces in Flanders. There was no way he could recapture Landau. More good news for the Allies came from northern Italy. On September 7, Prince Eugene completely defeated a French army near Turin, driving the French and Spanish forces out of northern Italy.

The only good news for King Louis XIV came from Spain. Allied forces had to retreat from Madrid, allowing Philip V to re-enter his capital on October 4. Overall, though, the situation had changed a lot, and King Louis XIV began looking for ways to end the war, which was becoming very costly for France. For Queen Anne of Great Britain, the Ramillies campaign was very important. She said, "Now we have God be thanked so hopeful a prospect of peace." However, disagreements among the Allies would later allow King Louis XIV to recover from some of these major setbacks.

Battle Losses

It's hard to know the exact number of French casualties because their army collapsed so completely. Historians estimate that between 12,000 and 15,000 French soldiers were killed or wounded, and another 7,000 to 10,000 were taken prisoner. Many more soldiers deserted, meaning they ran away and never returned to their army. The French defeat at Ramillies was a huge disaster for King Louis XIV.

Images for kids

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |