CSS Alabama facts for kids

class="infobox " style="float: right; clear: right; width: 315px; border-spacing: 2px; text-align: left; font-size: 90%;"

| colspan="2" style="text-align: center; font-size: 90%; line-height: 1.5em;" |

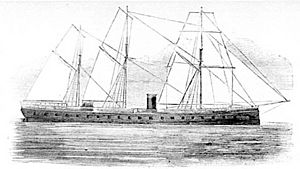

|} The CSS Alabama was a special kind of warship called a screw sloop-of-war. It was built in 1862 for the Confederate States Navy in England, at Birkenhead near Liverpool. The Alabama was very good at attacking Union merchant ships and naval vessels. It spent two years at sea without ever stopping at a Southern port. In June 1864, the Alabama was sunk by the USS Kearsarge during the Battle of Cherbourg in France.

Contents

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Alabama |

| Builder | John Laird Sons & Company |

| Laid down | 1862 |

| Launched | July 29, 1862 |

| Commissioned | August 24, 1862 |

| Motto | "Aide Toi, Et Dieu T'Aidera," (God helps those who help themselves) |

| Fate | Sunk June 19, 1864 |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement | 1050 tons |

| Length | 220 ft (67 m) |

| Beam | 31 ft 8 in (9.65 m) |

| Draft | 17 ft 8 in (5.38 m) |

| Installed power | 2 × 150 HP horizontal steam engines (300 HP collectively), auxiliary sails |

| Propulsion | Single screw propeller |

| Speed | 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph) |

| Complement | 145 officers and men |

| Armament | 6 × 32 lb (15 kg) cannons, 1 × 110 lb (50 kg) cannon, 1 × 68 lb (31 kg) cannon |

History of the Alabama

How was the Alabama built?

The Alabama was built in secret during 1862 by British shipbuilders John Laird Sons and Company. Their shipyards were in Birkenhead, England. A Confederate agent named Commander James Bulloch arranged for the ship to be built. He was in charge of getting much-needed ships for the new Confederate States Navy.

At the time, British law said that a ship could be built as a warship, but it couldn't be armed until it was in international waters. Because of this rule, the Alabama was built with strong decks for cannons and places to store ammunition below the water. However, it did not have any weapons or "warlike equipment" installed while it was in England.

The ship was first known only as "ship number 0290." It was launched as the Enrica on May 15, 1862. It secretly left Birkenhead on July 29, 1862. Union Captain Tunis A. M. Craven tried to stop the ship, but he failed.

Agent Bulloch arranged for a civilian crew to sail the Enrica to Terceira Island in the Azores. The ship's new captain, Raphael Semmes, left Liverpool on August 13, 1862, to take command. Captain Semmes arrived at Terceira Island on August 20, 1862. There, he started to equip the ship with weapons and 350 tons of coal. These supplies were brought by the Agrippina, which was the Enrica's supply ship.

After three days of hard work, the Enrica was ready to be a naval cruiser. It was officially named a commerce raider for the Confederate States of America. After it became the CSS Alabama, Bulloch went back to Liverpool to continue his secret work.

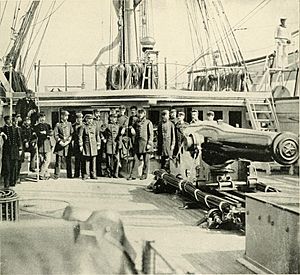

The Alabama's weapons were made in Britain. It had six 32-pounder cannons that fired from the sides. It also had two larger pivot cannons. These pivot cannons could turn to fire from either side of the ship. One was a powerful 100-pounder rifled cannon at the front. The other was a large 68-pounder smoothbore cannon at the back.

The Alabama could use both sails and a steam engine for power. It had a two-cylinder, 300-horsepower marine steam engine. This engine turned a single propeller. The ship's smokestack could be raised or lowered to help disguise it as a regular sailing ship. With its propeller pulled up, the Alabama could sail at ten knots. Using both sail and steam, it could reach 13.25 knots (24.54 km/h).

Starting the voyage

The ship was officially put into service on August 24, 1862. This happened about a mile off Terceira Island, in international waters. Captain Raphael Semmes read his orders from President Jefferson Davis. Musicians played "Dixie" as the ship's British flag was lowered. A cannon fired, and the new Confederate flag was raised. The ship was now the Confederate States Steamer Alabama. Its motto, "Aide-toi et Dieu t'aidera" (which means "God helps those who help themselves"), was carved into the ship's large steering wheel.

Captain Semmes then spoke to the seamen, many of whom were British. He asked them to join the Confederate Navy. At first, he only had 24 officers and no crew. So, Semmes offered signing money, double wages paid in gold, and extra prize money for every Union ship they destroyed. Eighty-three seamen, mostly British, agreed to join. Agent Bulloch and the other seamen returned to England. Semmes still needed about 20 more men for a full crew. He planned to recruit them from captured ships or friendly ports. Many of the original 83 crewmen stayed for the entire voyage.

Under Captain Semmes, the Alabama spent its first two months in the Eastern Atlantic. It captured and burned many Northern merchant ships. After a difficult trip across the Atlantic, it continued its attacks in the New England area. Then it sailed south to the West Indies, causing more trouble. Finally, it went west into the Gulf of Mexico.

In January 1863, the Alabama had its first battle. It found and quickly sank the Union side-wheeler USS Hatteras near Galveston. The Alabama captured the warship's crew. It then sailed further south, crossing the Equator. There, it captured the most prizes of its career while cruising off the coast of Brazil.

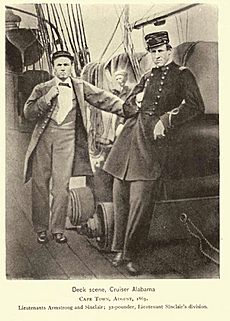

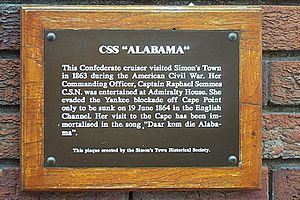

After another trip across the Atlantic, the Alabama sailed down the southwestern African coast. It continued its war against Northern trade. On July 29, 1863, it stopped in Saldanha Bay. Then, it made a much-needed stop in Cape Town, South Africa, to get supplies and repairs. The Alabama is even part of a popular Afrikaans folk song in South Africa called "Daar kom die Alibama."

It then sailed to the East Indies. There, it spent six months destroying seven more ships. Finally, it sailed around the Cape of Good Hope and headed for France. Union warships often hunted for the famous Confederate raider. But the few times the Alabama was spotted, it managed to escape its pursuers.

In total, the Alabama burned 65 Union ships, mostly merchant ships. During all its raids, the crews and passengers of captured ships were never hurt. They were only held until they could be put on a neutral ship or taken to a friendly port.

Worldwide raids

The Alabama went on seven major raids around the world. After these, it headed to France for repairs.

- Eastern Atlantic Raid (August–September 1862): Right after being commissioned, the Alabama sailed near the Azores. It captured and burned ten ships, mostly whaling vessels.

- New England Raid (October–November 1862): Captain Semmes and his crew went to the northeastern coast of North America. They sailed along Newfoundland and New England, reaching as far south as Bermuda. They burned ten ships and captured three others.

- Gulf of Mexico Raid (December 1862 – January 1863): The Alabama met its supply ship, CSS Agrippina. It also helped Confederate forces during the Battle of Galveston. During this time, it quickly sank the Union side-wheeler USS Hatteras.

- South Atlantic Raid (February–July 1863): This was its most successful raid. It captured 29 ships off the coast of Brazil. Here, it turned a captured ship called the Conrad into a Confederate warship, the CSS Tuscaloosa.

- South African Raid (August–September 1863): This raid happened mostly off the coast of South Africa. The Alabama worked with the CSS Tuscaloosa.

- Indian Ocean Raid (September–November 1863): The Alabama traveled almost 4,500 miles across the Indian Ocean. It avoided the Union gunboat Wyoming and captured three ships near the Sunda Strait.

- South Pacific Raid (December 1863): This was its last raid. It captured a few ships in the Strait of Malacca. Then, it finally turned back towards France for much-needed repairs.

After these seven raids, the Alabama had been at sea for 534 days out of 657. It never visited a single Confederate port. It stopped nearly 450 vessels. It captured or burned 65 Union merchant ships. It took more than 2,000 prisoners. Amazingly, no one on either side died during these captures.

The final battle

On June 11, 1864, the Alabama arrived in Cherbourg, France. Captain Semmes asked for permission to repair his ship in a dry dock. These repairs were badly needed after so much time at sea. Three days later, the American warship USS Kearsarge, commanded by Captain John Ancrum Winslow, arrived. It waited just outside the harbor. The Kearsarge had the Alabama trapped.

Captain Semmes did not want his worn-out ship to stay stuck in a French dock. He decided to fight. After preparing his ship and drilling his crew for several days, Semmes sent a challenge to the Kearsarge's commander. He stated his intention to fight the Kearsarge very soon.

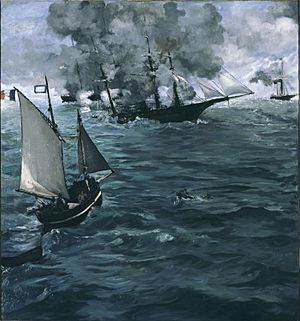

On June 19, the Alabama sailed out to meet the Union cruiser. Many people watched the battle, including the artist Édouard Manet.

As the Kearsarge turned to face its opponent, the Alabama fired first. The Kearsarge waited until the ships were less than 1,000 yards (900 m) apart. The two ships steamed in seven circles, each trying to get into a better position to fire. The battle quickly went against the Alabama. This was because the Kearsarge had better gunners. Also, the Alabama's gunpowder and fuses were old and not working well. One of the Alabamas most important shots hit near the Kearsarges steering part. This made the ship's rudder hard to move. But the shell did not explode. If it had, it could have sunk the Kearsarge.

Captain Semmes later said he did not know the Kearsarge had armor. He claimed he would not have fought if he had known. The Kearsarge's hull armor was put on a year before, in the Azores. It was made of 120 fathoms (about 720 feet) of thick iron chain. This chain covered a large part of the hull. It was hidden behind wooden boards painted black. This "chaincladding" protected the engine and boilers.

The Kearsarges armor was hit twice. One 32-pounder shell cut the chain armor and dented the hull. Another 32-pounder shell exploded, breaking a chain link and tearing away some of the wooden cover. If these shots had come from the Alabamas more powerful 100-pounder cannon, they might have gone through. But even then, they would have missed the vital machinery. However, a 100-pound shell could have caused a lot of damage inside the ship and hurt crewmen. It could also have started a fire, which was very dangerous on a wooden ship.

About an hour after the first shot, the Alabama was badly damaged. The Kearsarge's powerful 11-inch (280 mm) Dahlgren cannons had wrecked it. Captain Semmes had to lower his flag and send a boat to the Kearsarge to ask for help.

Witnesses said the Alabama fired 370 rounds. This was a very fast rate of fire. The Kearsarges gun crews fired less than half that number, taking more careful aim. Five more shots were fired at the Alabama even after its flag was lowered. This happened because its gun ports were still open, making it look like it was still fighting. Finally, a white flag was waved from the Alabamas stern, stopping the battle.

The Alabama's steering was damaged by shell hits. But the final, deadly shot came when one of the Kearsarges 11-inch (280 mm) shells tore open the Alabamas side near the waterline. Water quickly filled the ship, drowning its boilers and making it sink by the stern. As the Alabama sank, Captain Semmes threw his sword into the sea. This meant he did not hand it over to Captain Winslow, which was the usual way to surrender. Many people at the time thought this was dishonorable.

Out of 170 crew members, the Alabama had 19 deaths (9 killed and 10 drowned) and 21 wounded. The Kearsarge rescued most of the survivors. However, 41 of the Alabama's officers and crew, including Semmes, were rescued by John Lancaster's British steam yacht Deerhound. The Kearsarge could only watch as the Deerhound took Captain Semmes and his crew to England. Semmes eventually returned to the Confederacy and became an admiral near the end of the war.

The sinking of the Alabama by the Kearsarge is honored by the United States Navy.

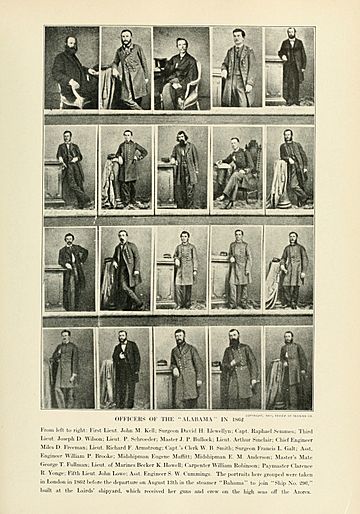

Officers of the Alabama

One very brave act during the Alabamas last moments involved the ship's assistant surgeon, Dr. David Herbert Llewellyn. Dr. Llewellyn was British and well-liked by everyone on the ship. During the battle, he stayed in the wardroom, helping the wounded. When the order came to abandon ship, he helped injured men into the Alabamas two working lifeboats. An able-bodied sailor tried to get into a full lifeboat. Dr. Llewellyn pulled him back, saying, "See, I want to save my life as much as you do; but let the wounded men be saved first."

An officer in the boat saw that Llewellyn was about to be left behind. He shouted, "Doctor, we can make room for you." Llewellyn shook his head and replied, "I will not peril the wounded." What the crew didn't know was that Llewellyn had never learned to swim. He drowned when the ship sank.

His sacrifice was remembered in England. A memorial window and tablet were placed in Easton Royal Church in his home village. Another tablet was placed in Charing Cross Hospital, London, where he studied medicine.

What happened next?

During its two years as a commerce raider, the Alabama caused a lot of damage to Union merchant ships around the world. The Confederate cruiser captured 65 ships. These ships were worth nearly $6,000,000 in 1864, which is a lot of money today.

After the war, the U.S. government made "Alabama Claims" against Great Britain. They said Britain was responsible for the losses caused by the Alabama and other ships built in Britain. A special commission decided that the U.S. should get $15.5 million in damages. This was an important step in international law.

Interestingly, ten years before the Civil War, Captain Semmes had said that commerce raiders were "little better than licensed pirates." He believed all civilized nations should stop them.

However, the Alabama and other raiders did not achieve their main goal. Their purpose was to make the Union move its ships away from the blockade of the Southern coastline. This blockade was slowly hurting the Confederacy. The Confederate government hoped that shipping companies' panic would force the Union to protect merchant ships. But Union officials kept the blockade strong. Even though insurance prices went up and many ships changed to a neutral flag, very few naval vessels were taken off the Southern blockade. The Union actually increased the blockade throughout the war. They also sent ships to protect merchant shipping and hunt down Confederate raiders.

Finding the wreck

In November 1984, the French Navy mine hunter Circé found a shipwreck. It was under nearly 200 ft (60 m) of water off Cherbourg. Captain Max Guerout later confirmed it was the remains of the Alabama.

In 1988, a group called the CSS Alabama Association was formed. Its goal was to explore the shipwreck scientifically. Even though the wreck is in French waters, the United States Government owns it. On October 3, 1989, the USA and France signed an agreement. They recognized the wreck as an important historical site for both nations. They also created a Joint French-American Scientific Committee for archaeological exploration. This agreement set an example for countries working together to study and protect historic shipwrecks.

The Association CSS Alabama and the Naval History and Heritage Command signed an agreement in 1995. This allowed the Association to lead the archaeological work on the ship's remains. The Association gets its money from private donations. It continues to make this an international project with fundraising in France and the USA.

The Alabama had eight cannons when it arrived at the Azores. Six of them were 32-pounder smoothbore cannons. Seven cannons have been found at the wreck site. Two were made in a British Royal Navy style. Three were made by Fawcett, Preston, and Company in Liverpool.

One of the 32-pounder cannons was found across the ship's right side, in front of the boilers. Another 32-pounder was found outside the hull, near the propeller. This front 32-pounder was brought up in 2000. Both of the British Royal Navy 32-pounders were found. One is inside the right side of the hull. The second was found on the iron deck structure, near the smokestack. It was brought up in 2001. The last 32-pounder has not been clearly identified yet.

The Alabama's heavy cannons were a 7-inch 100-pounder Blakely rifle at the front and a 68-pounder smoothbore at the back. The Blakely 7-inch 100-pounder was found next to its pivot carriage. This was the first cannon recovered from the Alabama. The 68-pounder smoothbore was found at the back of the ship. Both heavy cannons were brought up in 1994.

Besides the seven cannons, the wreck site had cannonballs, gun carriage wheels, and brass tracks for the gun carriages. Many of the brass tracks were recovered. Two cannonballs were found. One pointed shell was inside the barrel of the 7-inch Blakely rifle. A shell for a 32-pounder was found at the stern. Other round shots were seen near the boilers and the back pivot gun. One might have been fired from the Kearsarge.

In 2002, divers brought up the ship's bell. They also found over 300 other items. These included more cannons, parts of the ship's structure, tableware, and other objects. These items tell us a lot about life on the Confederate warship. Many of these items are now kept in a special lab at the Underwater Archaeology Branch, Naval History & Heritage Command.

Fun facts and legacy

The Alabama is the subject of a sea shanty called Roll, Alabama, Roll. This song was also used by the British folk band Bellowhead for a record in 2014.

The Alabama's visit to Cape Town in 1863 is part of South African folklore. It is mentioned in the Afrikaans song, Daar Kom die Alibama.

The Alabama Hills in California are named after the ship.

Flags of the Alabama

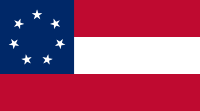

Confederate warships, like British ships, used different kinds of flags. These included jacks, commissioning pennants, battle ensigns, and signal flags.

Early flags

When the Alabama first started its raids, it might have flown an early 7-star "First National Flag." This might have been the same flag used on Captain Semmes's previous ship, the CSS Sumter. Later, more states joined the Confederacy, and more stars were added to the "Stars and Bars" flag.

One of these early "Stars and Bars" flags was found after the Alabama sank. It is now kept at the Alabama Department of Archives and History. This flag has eight white stars arranged in an unusual way. It seems this might have been the Alabama's original 7-star flag, which was later changed when news of an eighth state joining the Confederacy reached the ship.

Two other "Stars and Bars" flags, said to belong to the Alabama, still exist. One is a 14-star flag at the Mariner's Museum in Virginia. Another is at the Pensacola Historical Museum. Its canton (the blue corner) has a circle of 12 stars around a larger 13th star.

Later flags

Four of the Alabama's later flags, called "Stainless Banners," have survived.

- The first is in South Africa at Cape Town's Bo-Kaap Museum. Its Southern Cross canton is very large and rectangular. It does not have white stripes around its blue bars. A central white star is larger than the others. This flag was likely made by the British crew. It was given to William Anderson, whose company helped repair and supply the Alabama in Cape Town.

- A second Stainless Banner flag from South Africa was given to the Alabama in Cape Town. It is now in the Tennessee State Museum.

- The third surviving Stainless Banner is one of the Alabama's original small boat flags. This flag is marked "Alabama. 290. C.S.N. 1st Cutter." It was sold at auction in 2007.

- A fourth flag seems to be a larger replacement boat flag. It was rescued from the sinking Alabama by W. P. Brooks, the ship's assistant-engineer. This flag is still with the Brooks family today.

The Alabama Department of Archives and History also has a very important Stainless Banner flag. It is called "Admiral Semmes' Flag." This huge flag is made of pure silk. It was given to Semmes by "Lady Dehogton and other English ladies" after the Alabama sank. When Semmes returned to the Confederacy, he brought this flag with him. It was later donated to the state of Alabama in 1929.

See also

In Spanish: CSS Alabama para niños

In Spanish: CSS Alabama para niños