Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Count of Mirabeau

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait of Mirabeau by Joseph Boze (1789)

|

|

| Member of the Constituent Assembly from Provence |

|

| In office 9 July 1789 – 2 April 1791 |

|

| Constituency | Aix-en-Provence |

| Member of the Estates-General for the Third Estate |

|

| In office 5 May 1789 – 9 July 1789 |

|

| Constituency | Provence |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 9 March 1749 Le Bignon, Orléanais, France |

| Died | 2 April 1791 (aged 42) Paris, Seine, France |

| Political party | National Party (1790–1791) |

| Spouses |

Émilie de Covet, Marchioness of Marignane

(m. 1772; div. 1782) |

| Children | Victor (d. 1778) |

| Parents | Victor de Riqueti, marquis de Mirabeau Marie-Geneviève de Vassan |

| Alma mater | Aix University |

| Profession | Soldier, writer, journalist |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Royal Army |

| Years of service | 1768–1769 |

| Rank | Sub lieutenant |

| Battles/wars | Conquest of Corsica |

Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, Count of Mirabeau (born March 9, 1749 – died April 2, 1791) was an important leader in the early days of the French Revolution. Even though he came from a noble family, he had a difficult reputation before 1789. However, he quickly became a top political figure between 1789 and 1791. People saw him as a strong voice for the common people.

Mirabeau was a skilled speaker. He supported a constitutional monarchy, which means a king or queen would rule alongside an elected government, similar to the system in Great Britain. When he died naturally, he was considered a national hero. Later, it was discovered that he had secretly received money from King Louis XVI and the Austrian government. This led to him being seen in a negative light after his death. Historians still debate whether he was a great leader, a dishonest politician, or even a traitor.

Contents

Mirabeau's Family History

The Riqueti family, possibly from Italy, became very rich through trading in Marseilles. In 1570, Jean Riqueti bought the castle and land of Mirabeau. In 1685, Honoré Riqueti received the title "marquis de Mirabeau."

Mirabeau's grandfather, Jean Antoine, was a brave soldier for King Louis XIV. He was wounded in battle and had to wear a silver neck brace. Because he was very direct, he never became a high-ranking officer. He had three sons, and Honoré Gabriel Riqueti was the son of the eldest, Victor.

Mirabeau's Early Life

Honoré-Gabriel Mirabeau was born in Le Bignon, France. He was the eldest son of the economist Victor de Riqueti, marquis de Mirabeau. When he was three, he got smallpox, which left his face scarred. His father didn't like him much, partly because of this and because Mirabeau looked like his mother's family.

At age five, his father sent him to a strict boarding school in Paris. He was meant to join the army and entered military school at eighteen. After school in 1767, he joined a cavalry regiment.

Mirabeau had personal troubles that led to scandal. His father used a lettre de cachet to have him imprisoned. A lettre de cachet was a royal order that allowed someone to be jailed without a trial. After being released, he joined a French military trip to Corsica. He showed military skill and studied the island's customs. This curiosity helped him later in the Revolution.

In 1772, he married a wealthy heiress, Marie–Marquerite–Emilie de Covet. Mirabeau was in debt and couldn't afford his wife's expensive lifestyle. His father sent him away to the countryside. There, he wrote his first work, Essai sur le despotisme (Essay on Despotism). Their son died young due to poor living conditions. His wife later asked for a legal separation in 1782. Mirabeau defended himself in court but lost.

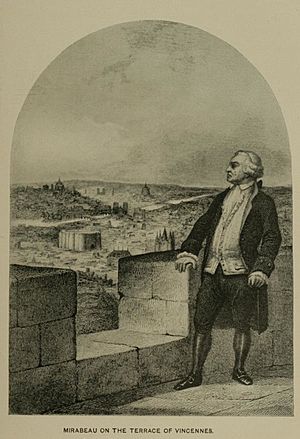

His strong personality led to more conflicts. He was imprisoned again in the Château d'If in 1774, then moved to the castle of Joux in 1775. He later escaped to Switzerland and then to the Dutch Republic. He was caught by Dutch police in May 1777 and sent back to France. He was then imprisoned in the castle of Vincennes.

While in prison, he wrote Des Lettres de Cachet et des prisons d'état (On Letters of Cachet and State Prisons). This book was published after he was freed in 1782. It showed that the system of lettres de cachet was unfair and against French law. This work showed Mirabeau's deep knowledge of history and his strong speaking skills.

Before the French Revolution

Mirabeau was released from Vincennes in August 1782. He managed to overturn his death sentence and gained public support. People started to see him as a champion of the common person. He tried to get his wife to return to him, but she refused, and he lost in court. He then criticized the government so strongly that he had to leave France again for the Dutch Republic.

Around this time, he met Madame de Nehra, who was a kind and educated woman. She brought stability to his life. After some time in the Dutch Republic, he went to England. His book on lettres de cachet was well-received there. He became friends with important British politicians like Gilbert Elliot.

In 1785, Mirabeau wrote several works, including Considérations sur l'ordre de Cincinnatus. This book criticized a new American society formed by officers of the American Revolutionary War. Benjamin Franklin even helped him with information for the book. Mirabeau also wrote pamphlets criticizing financial speculation, like De La Caisse d'Escompte. These writings were influential in criticizing the French government before the Revolution.

He tried to get a job with the French foreign office, but his strong criticisms of government finance ruined his chances. However, his talents were too great to be ignored. In 1786, he was sent on a secret mission to the royal court of Prussia. When he returned, he published Secret History of the Court of Berlin (1787). This book described the Prussian court as corrupt and criticized its leaders. This caused a huge scandal for the French government, but it made Mirabeau even more popular with those who wanted change.

In 1788, Mirabeau was asked to be a secretary for the Assembly of Notables. This was a group called by King Louis XVI to try and fix France's tax problems. Mirabeau turned down the offer. He continued to publish financial writings that further hurt his chances with the government. But then, 1789 arrived, the Estates-General was called, and the French Revolution began. This new situation allowed Mirabeau to become a very influential political figure.

The French Revolution

1789: A Voice for the People

When King Louis XVI decided to call the Estates-General, Mirabeau went to his home region of Provence. He tried to join the meeting of the nobility (the Second Estate), but they rejected him. So, he turned to the Third Estate (the common people) and was elected to the Estates-General for both Aix and Marseilles. He chose to represent Aix.

From the start, Mirabeau played a very important role in the National Constituent Assembly. He was already well-known to the French public. People trusted him, but also feared his strong personality. He was known for his hard work and vast knowledge.

Mirabeau believed that government should allow people to live peacefully. He understood that a strong government needed to listen to the people. He had studied the British government and wanted to create a similar system in France. In the early meetings of the Estates-General, Mirabeau quickly became a leader. He is credited with helping to form the National Assembly from the Estates-General.

On June 23, 1789, during a royal meeting of the National Assembly, the king's messenger ordered them to break up. Mirabeau famously replied, "Tell those who send you that we are here by the will of the people and will leave only by the force of bayonets!"

After the storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, Mirabeau warned the Assembly that simply making decrees wasn't enough; they needed to act. He worried that armed crowds would lead the Revolution down a violent path. He felt that the "Night of August 4" (when feudalism was abolished) gave people theoretical freedom but no real freedom. He believed the old system was destroyed before a new one could be built.

Mirabeau wanted to create a strong government like the British system, with ministers who answered to the people's representatives. He believed this assembly should represent the French people better than the British Parliament represented its people. He also helped the Assembly write the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in August 1789.

1790–1791: Working with the King

In June 1790, Mirabeau met Queen Marie Antoinette at Saint Cloud. He stayed in close contact with her and helped write many government papers for the royal family. In return, the king secretly paid his debts and gave him a monthly allowance. Some historians believe Mirabeau was not a traitor. They argue he tried to bridge the gap between the king and the revolutionaries while still holding onto his political beliefs.

Mirabeau focused on two main goals: changing the government leadership and dealing with the possibility of civil war. His attempts to work with other leaders like Lafayette failed. Mirabeau suggested that the king should step back from politics and let the Revolution run its course. He thought it would eventually collapse on its own. He also suggested that if his plan failed, Paris should no longer be the capital of France.

Mirabeau believed that civil war was unavoidable and even necessary for the monarchy to survive. He thought the king should be the one to declare war. However, King Louis XVI, as a Christian king, said he could not declare war on his own people. He hoped for a constitution he could agree to. When the Civil Constitution of the Clergy of 1790 destroyed this hope, the king decided to strengthen royal power and the church's position, even if it meant using force.

Mirabeau supported the king's power regarding the royal veto. He believed the king should have an absolute veto (the power to stop any law indefinitely). He knew from British experience that this would only work if the king had the people's support. The final decision was to give the king a suspensive veto, meaning he could delay a law for two years.

On the issue of peace and war, Mirabeau supported the king's authority. He argued that soldiers must obey orders and give up some of their freedom to think and act. He also approved of the strong actions taken by the marquis de Bouillé at Nancy, even though Bouillé was his opponent.

In financial matters, he criticized the "caisse d'escompte" (discount bank) for taking too much control over taxes. He supported the use of assignats (paper money), but only if their value was limited to half the value of the lands being sold.

Mirabeau saw that the National Assembly was often inefficient because its members were inexperienced and talked too much. He asked his friend Samuel Romilly to write down the rules of the British Parliament, which he translated into French. However, the Assembly refused to use them.

Jacobin Club

Mirabeau was also a member of the Jacobin Club until his death. Some historians believe he was a Jacobin only in name, seeing the club as an obstacle to his plans to restore royal power. However, in the early years of the Revolution, Mirabeau was a leading figure in the club. He reached the peak of his influence when he was elected its president in December 1790.

During his time in the Jacobin Club, he influenced decisions about selling church land, the slave trade, and who could join the National Guard. Mirabeau argued for selling church lands to private citizens to help France's financial problems. His fellow Jacobins strongly supported this idea. Although Mirabeau argued for the abolition of slavery, the clubs were generally slow to act on this issue until later in the Revolution.

Regarding the National Guard, a law passed on December 6, 1790, stated that only "active citizens" could serve. An "active citizen" was someone whose annual tax was equal to three days' work. This meant that only middle and upper-class people could join the National Guard.

This law led to heated debates in the Jacobin Clubs, especially in Paris. It also created a conflict between Mirabeau and Maximilien Robespierre, who was becoming a powerful political figure. The evening the law passed, Robespierre tried to speak against it at the Jacobin club but was stopped by Mirabeau. Mirabeau argued that no one should challenge a law already passed by the National Assembly. After a long uproar, Robespierre was allowed to finish. Historians believe Mirabeau tried to stop Robespierre because he saw the Revolution becoming more extreme, led by radical Jacobins. Mirabeau was part of a more moderate group called the Société des amis de la Révolution de Paris, which disappeared by 1790.

After Mirabeau's death, the Jacobin Clubs mourned him deeply. However, this didn't last long. In 1792, after the monarchy was overthrown, letters were found in an iron chest. These letters showed Mirabeau's secret dealings with the king to try and save the monarchy. This led to his statue being destroyed in the Jacobin Club. Robespierre then denounced him as a "political trickster unworthy of honor."

Foreign Affairs

In foreign policy, Mirabeau believed that the French people should manage their revolution without other countries interfering. However, he knew that neighboring nations were worried about the Revolution's spread and that French nobles who had fled the country were asking foreign kings to help the French monarchy. Mirabeau's main goal was to prevent this interference.

He was elected to the Assembly's diplomatic committee in July 1790. In this role, he prevented the Assembly from making mistakes in foreign policy. He had known Armand Marc, comte de Montmorin, the foreign secretary, for a long time. As tensions grew, Mirabeau communicated with Montmorin daily, advising him on every issue and defending his policies in the Assembly. Mirabeau's efforts showed he was a true statesman. The confused state of foreign affairs after his death shows how important his influence was.

Mirabeau's Death

Mirabeau's health was poor due to his difficult youth and hard work in politics. In 1791, he became very ill with a heart condition. Despite constant care from his friend and doctor, Pierre Jean George Cabanis, Mirabeau continued his duties as president of the National Assembly until he died on April 2, 1791, in Paris. Even near the end, he led debates with great skill, which made him even more popular. The people of Paris saw him as one of the Revolution's founders.

He received a grand funeral. The Panthéon in Paris was created as a burial place for great French people, and he was the first to be buried there. The street where he died was renamed rue Mirabeau.

However, during the Trial of Louis XVI in 1792, Mirabeau's secret dealings with the royal court were revealed. He was largely disgraced by the public when it became known that he had secretly worked between the monarchy and the revolutionaries and had been paid for it. In 1794, his remains were removed from the Panthéon and replaced with those of Jean-Paul Marat. His remains were then buried secretly in a graveyard. Despite searches in 1889, they were never found.

Mirabeau's death made it much harder to save the monarchy. The king was less willing to compromise with the Revolution, and revolutionary leaders were less willing to share power with a king who seemed so unwilling to cooperate. Some historians believe that even if Mirabeau had lived, the outcome would have been similar. It would have been very difficult to bring back the old monarchy while democratic ideas were growing so strong.

Mirabeau proved to be one of the strongest early leaders of the Revolution. His energy captivated his audience, and his leadership often guided revolutionary ideas. His work with the king, however, damaged his reputation. Mirabeau's early life, though full of rebellion against his strict father, helped him develop these qualities.

Collaborators

Mirabeau often worked with others on his writings and speeches. His first major work, Essai sur le despotisme (1775), was followed by a translation of Philip II with help from Nicolas-Luton Durival. His Considerations sur l'ordre de Cincinnatus (1788) was based on a pamphlet by Aedanus Burke, and the notes were by Gui-Jean-Baptiste Target. His writings on finance were inspired by Étienne Clavière.

During the Revolution, many people helped him. They were proud to work for him, even if he received all the credit. Some of his most famous helpers included Étienne Dumont, who prepared his eloquent speeches, and Clavière, who helped with financial figures and speeches. Antoine-Adrien Lamourette wrote speeches on the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. Étienne Salonion Reybaz wrote many of his famous speeches, including those on assignats and the national guard. Reybaz even wrote a speech that Charles Maurice de Talleyrand read in the Assembly after Mirabeau's death.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Honoré Gabriel Riquetti para niños

In Spanish: Honoré Gabriel Riquetti para niños

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |