Casey Hayden facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Casey Hayden

|

|

|---|---|

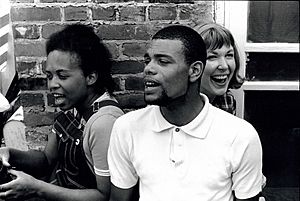

Hayden (R) with Dorie A Ladner and Cardell Reagan, Greenwood, Mississippi, July 1963

|

|

| Born |

Sandra Cason

October 31, 1937 Austin, Texas, U.S.

|

| Died | January 4, 2023 (aged 85) Arizona, U.S.

|

| Occupation | Civil rights activist |

| Movement | Students for a Democratic Society, Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party |

Sandra Cason Hayden (born October 31, 1937 – died January 4, 2023) was an American student who worked for civil rights in the 1960s. She was known for supporting direct action (taking immediate steps) to fight against racial segregation. In 1960, she joined the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).

Later, with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Mississippi, Hayden helped plan and organize the 1964 Freedom Summer. This project aimed to register African American voters. She believed in a "radically democratic" movement. This meant that people working on the ground should lead the movement. She also felt that this approach helped women's voices be heard.

In November 1965, Hayden and Mary King wrote a paper called "Sex and Caste." It compared the experiences of women to those of African Americans. They suggested that women were "caught up in a common-law caste system." This system often forced them to work outside the usual power structures. This paper is seen as an important link between the civil rights movement and the women's liberation movement. Hayden said publishing it was her "last action as a movement activist."

For many years after, she continued to believe that the civil rights struggle paved the way for women. It also inspired others to "organize for themselves."

Contents

Early Life and Family

Casey Hayden was born Sandra Cason on October 31, 1937. Her hometown was Austin, Texas. She was a fourth-generation Texan. She grew up in Victoria, Texas. She lived with her mother, her mother's sister, and her grandmother. This was an unusual family setup for the time. Hayden believed it helped her understand people who were often left out.

Becoming a Campus Activist

In 1957, Sandra Cason started college at The University of Texas. She joined the Christian Faith and Life Community, which welcomed people of all races. She became active in civil rights education and protests. She was an officer for the Young Women's Christian Association. She also joined the Social Action Committee.

While studying English and philosophy, she helped with sit-ins. These protests successfully ended segregation in restaurants and theaters in Austin. In August 1960, Cason spoke at a big student meeting. She argued against a plan that would not support the new Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). She said, "I cannot say to a person who suffers injustice, ‘Wait.’" Her powerful speech earned her a standing ovation.

Working with SNCC in the South

In the summer of 1961, Cason moved to New York City. She married Tom Hayden in October. They then moved to Atlanta. Ella Baker, a key leader in SNCC, hired Cason (now Casey Hayden). Hayden worked on a special project for the YWCA. She traveled to colleges in the South. There, she led workshops on race relations. She also helped prepare for the Freedom Riders. These brave activists challenged segregation on buses. In December, the Haydens were arrested in Albany, Georgia, as Freedom Riders.

While in jail, Tom Hayden started writing the Port Huron Statement. This important document guided the Students for a Democratic Society. Casey Hayden returned to Atlanta to work with SNCC. She and Tom Hayden separated and later divorced in 1965. Casey felt that SNCC, with its focus on action, valued relationships more. She also saw that women, especially Black women, were encouraged to speak out.

In 1963, Casey Hayden moved to Mississippi. She and Doris Derby started a literacy project. It was at Tougaloo College, a Black community near Jackson. As a white woman, her presence in the field could be risky. But she felt it was important to support the movement from behind the scenes. She saw herself as a "support person." She believed her role was to help, not to be a public leader.

Hayden felt that her ability to make decisions was not about her official title. She noted that SNCC made decisions together, like a town hall meeting. Being on the Executive Committee did not give much more power. She could control her own work and make choices.

In 1964, she became an organizer for Freedom Summer. She also worked for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. This group challenged the all-white delegation at the 1964 Democratic National Convention. Hayden explained her role: "I did the work all the way up and down. That means I did my own typing and mimeographing and mailing. I also did my own research and analysis and writing and decision making. The latter usually in conversation with other staff. As we said at the time, both about our constituencies and ourselves, 'The people who do the work should make the decisions.'"

She added that there were no secretaries in SNCC. This meant there was no office hierarchy. She felt she was at the center of the organization. She was free to think, do, grow, and care.

However, some people felt that the idea of a "beloved community" was fading. Elaine DeLott Baker, another activist, noticed a hidden hierarchy. Black men were at the top, then Black women, then white men, and white women at the bottom. Even so, women still had a lot of freedom to act. They were "keeping things moving." But their contributions were not always publicly recognized.

After Freedom Summer, everyone in the movement was tired from the violence. There were many new white volunteers. The Democratic Party also refused to seat the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. This made SNCC question their work on voter registration. A retreat was held in November in Waveland, Mississippi. This was a chance to think about the movement's future.

"Sex and Caste" Paper

At the Waveland retreat, a paper called "name withheld by request" was shared. It pointed out that the committee formed to change SNCC's rules was "all men." Casey Hayden and Mary King were soon known as the authors. Other women in the Jackson office also helped write it.

The paper said that "assumptions of male superiority" were like "white supremacy." They were "crippling to the woman." Many women, it said, acted like a "caricature of what a woman is—unthinking, pliable, an ornament to please." Hayden said they did not demand that SNCC focus on women's roles. The movement already had many challenges. Instead, the paper aimed to start conversations among SNCC women. This would strengthen their bonds and the movement.

In the new year, Hayden decided to expand the paper. She finalized a version with Mary King. They shared it with 40 other women. Most of these women had strong ties to SNCC. This paper later became known as a key text for second-wave feminism.

Hayden avoided using strong feminist language in the paper. She used the language of race relations instead. She wrote: "There seem to be many parallels that can be drawn between treatment of Negroes and treatment of women in our society as a whole." She added that women in the movement were "caught up in a common-law caste system." This system often forced them to work outside the usual power structures.

In November 1965, the paper was published in Liberation magazine. The editor suggested the title "Sex and Caste." Hayden said this was her "last action as movement activist."

Disagreements with SNCC Leaders

In April 1965, at an SNCC meeting, Hayden was called a "floater." This was a term for staff members who seemed too independent. Hayden had also written another paper at Waveland. It was about how SNCC should be organized.

SNCC leader James Forman wanted a stronger structure for the group. Hayden agreed that some structure was needed. But she wanted to keep SNCC's focus on organizers in the field. She wanted to respect how the group had grown naturally. Her plan aimed to keep leadership driven by people working on the ground. She did not want it to come from a central office.

Forman and others wanted a more political direction. They wanted to build a "Black Belt political party" in the South. Later, they considered organizing in Northern cities. Hayden believed that a grassroots organization would give women more influence. She later thought that "patriarchy was an issue."

At her last SNCC meeting in November 1965, Hayden told leaders that the power in SNCC was unbalanced. She felt they needed to step down for the movement to remain "radically democratic." She believed that a "looser structure" was not "no structure," but a "different structure."

Looking Back at the Movement

In 1986, Casey Hayden was interviewed for a TV series called Eyes on the Prize. She talked about the divisions between Black and white members in SNCC. She understood that local Black staff felt frustrated. They were the "backbone" of the project. They had to deal with many young white people who had more money and education.

She believed that calls for "Black Power" came later. They were a reaction to continued political exclusion. The refusal to recognize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party at the Democratic convention showed this. Hayden said, "it was like, if you won't let us in, we'll do our own thing."

But division was not her main memory of the movement. She remembered being "part of a visionary community." It truly went beyond race and was integrated. She felt its loss deeply. She also remembered it as "a lot of fun." She said, "We were all out there doing whatever we thought up to do. We were totally self-directed people."

She believed the movement inspired many people. It helped them "organize for themselves." This led to anti-war and women's organizing. She also noted the "patience and spirituality" of the Black community in the South. She felt she and others learned from this.

Later Years and Continued Activism

After 1965, Hayden worked for the New York Department of Welfare. Then she moved to a rural community in Vermont. She studied Zen Buddhism. She also became active in the home birth movement. She had two children with Donald Campbell Boyce III.

In 1981, Hayden returned to Atlanta. She worked for the Southern Regional Council, focusing on voter education and registration. Later, she worked for Andrew Young, a former assistant to Martin Luther King Jr. She was an administrative aide in the Department of Parks, Recreation and Culture.

In 1994, she married Paul Buckwalter. They lived in Tucson, Arizona. She helped care for his seven stepchildren. Paul Buckwalter was a priest and a leader in the Sanctuary movement. In 2010, Hayden spoke out against Arizona SB 1070. This state law made it a crime to help undocumented immigrants. She called it "Fortress America." She felt it showed a mindset of "We’ve got it and we are keeping it."

Casey Hayden passed away in Arizona on January 4, 2023, at age 85. She is survived by her son, Donald Campbell Boyce IV, her daughter, Rosemary Lotus Boyce, and her sister, Karen Beams Hanys.

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |