Unita Blackwell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

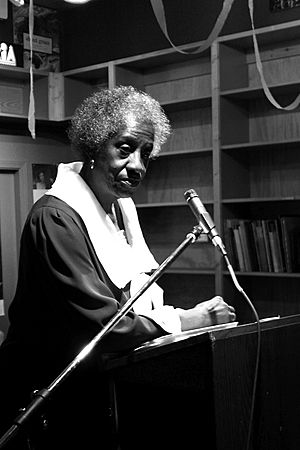

Unita Blackwell

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Mayor of Mayersville, Mississippi | |

| In office 1976–2001 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born |

U. Z. Brown

March 18, 1933 Lula, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died | May 13, 2019 (aged 86) Biloxi, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses | Jeremiah Blackwell Willie Wright |

| Children | 1 |

| Education | University of Massachusetts Amherst (MRP) |

| Occupation | Activist |

Unita Zelma Blackwell (born March 18, 1933 – died May 13, 2019) was an important American civil rights activist. She was the first African-American woman to be elected mayor in the state of Mississippi.

Blackwell worked as a project director for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). She helped organize many efforts to help African Americans register to vote across Mississippi. She also helped start the US–China Peoples Friendship Association. This group works to build friendships and understanding between the United States and China. Unita Blackwell also advised six U.S. Presidents. These included Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, and Bill Clinton.

Her autobiography, Barefootin', was published in 2006. It tells the story of her life and her work as an activist.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Blackwell was born U. Z. Brown on March 18, 1933. She was born in Lula, Mississippi. Her parents, Virda Mae and Willie Brown, were sharecroppers. This meant they farmed land owned by someone else and paid rent with a share of their crops.

Her uncle gave her the name "U. Z." She used these initials until she was in the sixth grade. Her teacher told her she needed a "real name." Together, they chose Unita Zelma.

When Unita was three, her father left their farm. He feared for his life after speaking up to his boss. Unita and her mother soon moved to live with him in Memphis, Tennessee. Her family often moved to find work.

In 1938, her parents separated. Unita and her mother moved to West Helena, Arkansas. They lived with her great aunt so Unita could go to school. Schools for Black children in Mississippi often focused on farm work. Children could only attend for two months before returning to the cotton fields.

While in West Helena, Unita often visited her father in Memphis. In the summers, she stayed with her grandparents in Lula. She helped plant and pick cotton. Unita spent many years chopping cotton for $3 a day. She worked in Mississippi, Arkansas, and Tennessee. She also peeled tomatoes in Florida.

She finished the eighth grade when she was 14. This was the last year of school at Westside, a school for Black children in West Helena. Unita had to leave school to help her family earn money.

Marriage and New Home

When she was 25, Unita met Jeremiah Blackwell. He was a cook for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. A few years later, they married in Clarksdale, Mississippi.

In 1957, Unita became very ill. She was taken to the hospital and was thought to have died. But she was later found alive in her hospital room. She said she had a near-death experience. On July 2, 1957, their only son, Jeremiah Blackwell Jr. (Jerry), was born.

In 1960, Jeremiah's grandmother passed away. The Blackwells moved into the small house she left him in Mayersville, Mississippi. This town had about 500 people. The family later built a larger brick home. But Unita wanted to keep the smaller house from Jeremiah's grandmother. After moving to Mayersville, Blackwell became involved in the Civil Rights Movement.

Civil Rights Activism

Unita Blackwell first joined the Civil Rights Movement in June 1964. Two activists from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee came to Mayersville. They held meetings in her church about the right of African Americans to vote.

The next week, Unita and seven others went to the courthouse. They wanted to take a test to register to vote. While they waited, white farmers tried to scare them away. Her group stayed all day. But only two of them could take the test. Blackwell said this day was "the turning point" of her life. The next day, Unita and Jeremiah lost their jobs. Their employer found out they tried to register to vote.

Blackwell tried to pass the voter registration test three times. In the fall, she passed and became a registered voter. Because of her work with voter registration, she and other activists faced constant harassment.

Working with SNCC

In the summer of 1964, Blackwell met Fannie Lou Hamer. After hearing Hamer's stories, Blackwell joined the SNCC. As a project director for SNCC, she organized voter registration drives across Mississippi.

Later that year, she joined the executive committee of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). This party gave a voice to the voters SNCC had helped register. In August, she and 67 other MFDP delegates went to the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey. They wanted the MFDP to be recognized as the true representatives from Mississippi. They were offered two seats, but they refused. This event, especially Hamer's televised speech, brought attention to the party and the civil rights movement in Mississippi.

Blackwell also helped start Head Start programs for Black children in the Mississippi Delta in 1965. This project was led by the Child Development Group of Mississippi.

In the late 1960s, Blackwell worked with the National Council of Negro Women. In the 1970s, she worked on a program for low-income housing. She encouraged people to "build their own homes." During her time in the Civil Rights Movement, she was jailed more than 70 times for her actions.

Blackwell v. Issaquena County Board of Education

The Blackwell family filed a lawsuit called Blackwell v. Issaquena County Board of Education. This happened on April 1, 1965. The principal had suspended over 300 Black children, including Unita's son Jerry. They were suspended for wearing pins that showed a black hand and a white hand clasped together with "SNCC" written below.

The lawsuit also asked the school district to end segregation in their schools. This was required by the Supreme Court's ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. A court decided that the pins were disruptive. But it also ordered the school district to desegregate their schools by the fall of 1965. The case went to a higher court in 1966, which agreed with the earlier decision. Blackwell called this case "one of the very first desegregation cases in Mississippi."

Blackwell's son and about 50 other children boycotted the school. They did this because the school would not let them wear the SNCC freedom pins. So, Blackwell and other activists opened Freedom Schools in Issaquena County. These schools became popular and taught classes every summer until 1970. That's when the local schools finally ended segregation.

Political Career and Later Life

Starting in 1973, Blackwell made 16 trips to China. One trip was with actress Shirley MacLaine to film The Other Half of the Sky. Blackwell was president of the US–China Peoples Friendship Association for six years. This group works to promote cultural exchange between the U.S. and China. In 1979, Blackwell was appointed to a U.S. commission for the International Year of the Child.

She was elected mayor of Mayersville, Mississippi, in 1976. She held this job until 2001. This made her the first African-American woman mayor in Mississippi. As mayor, she oversaw the building of public housing. This was the first time federal housing had been built in Issaquena County.

Blackwell got federal money for Mayersville. This money helped provide police and fire protection, a public water system, paved streets, and housing for the elderly and disabled. She became well-known for traveling to promote low-income housing.

Blackwell also served on the Democratic National Committee. She was also co-chairman of the Mississippi Democratic Party. Her work at the 1964 Democratic National Convention helped lead to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In 1982, Blackwell went to the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She earned a Master of Regional Planning degree. Even though she did not finish high school, a program helped her get into the university. They gave her credit for her activism and life experience.

She helped start Mississippi Action for Community Education (MACE). This group works on community development in Greenville, Mississippi. From 1990 to 1992, Blackwell was president of the National Conference of Black Mayors. In 1991, she helped create the Black Women Mayors' Conference and was its first president.

Blackwell became a strong voice for rural housing and development. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter invited her to an energy meeting. In 1992, she received a $350,000 MacArthur Fellowship "genius grant." This was for her creative solutions to housing and infrastructure problems. Blackwell ran for Congress in 1993 but was not elected.

Her autobiography, Barefootin': Life Lessons from the Road to Freedom, was published in 2006. It tells her life story, from sharecropping to becoming mayor.

Health and Passing

In 2008, Blackwell was reported to be in the early stages of dementia. She passed away on May 13, 2019, at a hospital in Ocean Springs, Mississippi. Her son said she died from heart and lung problems and complications from dementia. She is survived by her son, two grandchildren, and other family members.

Honors and Awards

- Named a fellow at the Institute of Politics at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

- Received a Master's Degree from the University of Massachusetts in 1983.

- Won the MacArthur Foundation Genius Grant in 1992.

- Received an honorary doctor of law degree from the University of Massachusetts in 1995.

- The University of Massachusetts recognized her belief in "educating by doing and being."

- Received the For My People Award from Jackson State University.

Tributes

- Blackwell is featured in Standing on My Sisters' Shoulders. This movie tells the stories of women in the civil rights movement in Mississippi.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Unita Blackwell para niños

In Spanish: Unita Blackwell para niños