John Lewis facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Lewis

|

|

|---|---|

Lewis in 2006

|

|

| House Democratic Senior Chief Deputy Whip | |

| In office January 3, 2003 – July 17, 2020 |

|

| Leader | Dick Gephardt Nancy Pelosi |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | G. K. Butterfield |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Georgia's 5th district |

|

| In office January 3, 1987 – July 17, 2020 |

|

| Preceded by | Wyche Fowler |

| Succeeded by | Kwanza Hall |

| Member of the Atlanta City Council from at-large post 18 |

|

| In office January 1, 1982 – September 3, 1985 |

|

| Preceded by | Jack Summer |

| Succeeded by | Morris Finley |

| 3rd Chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee | |

| In office June 1963 – May 1966 |

|

| Preceded by | Charles McDew |

| Succeeded by | Stokely Carmichael |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

John Robert Lewis

February 21, 1940 Pike County, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | July 17, 2020 (aged 80) Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Resting place | South-View Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Lillian Miles

(m. 1968; died 2012) |

| Children | 1 |

| Education |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Signature |  |

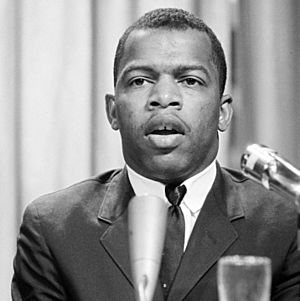

John Robert Lewis (born February 21, 1940 – died July 17, 2020) was an American politician and a brave civil rights activist. He worked hard to end racial segregation in the United States. Segregation meant keeping people of different races separate, which was unfair.

In 1961, John Lewis became one of the first 13 Freedom Riders. These were people who rode buses together to challenge unfair laws. He was also one of the "Big Six" leaders. These leaders organized the famous 1963 March on Washington. In 1965, Lewis became well-known for his important role in the Selma to Montgomery marches.

Contents

Early Life and Education

John Robert Lewis was born on February 21, 1940, near Troy, Alabama. He was the third of ten children. His parents, Willie Mae and Eddie Lewis, were sharecroppers. This meant they farmed land owned by someone else and paid rent with a share of their crops.

Lewis grew up in a very poor, rural area. He had little contact with white people because his county was mostly Black. By age six, he had only seen two white people in his life. He remembered, "I grew up in rural Alabama, very poor, very few books in our home."

He went to a small school close to his home. It was a "Rosenwald School," built to help educate Black children. He said, "I had a wonderful teacher in elementary school, and she told me 'read my child, read!'" Lewis loved books. In 1956, at age 16, he tried to get a library card with his family. But they were told the library was "for whites only."

As he got older, Lewis saw more racism and segregation in Troy. He learned from relatives in northern cities that schools, buses, and businesses there were not segregated. When he was 11, an uncle took him to Buffalo, New York. This trip made him realize how different and unfair segregation was in Alabama.

In 1955, Lewis first heard Martin Luther King Jr. on the radio. He then closely followed King's Montgomery bus boycott later that year. This boycott was a major protest against segregated buses.

Lewis wrote to King after being denied entry to Troy University because he was Black. King invited Lewis to meet him. King called Lewis "the boy from Troy." They talked about suing the university. But King warned Lewis that this could put his family in danger. After talking with his parents, Lewis decided to go to a small, historically black college in Tennessee instead.

Lewis graduated from the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee. He became a Baptist minister. He then earned a bachelor's degree in religion and philosophy from Fisk University. This was another historically black college.

Becoming an Activist

As a student, John Lewis became a key activist in the civil rights movement. He helped organize sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Nashville. Sit-ins were protests where people would sit at "whites-only" counters and refuse to leave. He joined many other civil rights activities as part of the Nashville Student Movement.

The Nashville sit-in movement helped end segregation at lunch counters in the city. Lewis was arrested and jailed many times during these peaceful protests. He also helped organize bus boycotts and other nonviolent actions. These protests aimed to gain voting rights and equal treatment for all races.

Lewis often said it was important to get into "good trouble, necessary trouble" to make change happen. He lived by this idea his whole life.

The Freedom Riders

The Freedom Rides started to make the government enforce a Supreme Court decision. This decision said that segregated bus travel between states was against the law. At 21, Lewis was one of the 13 original Freedom Riders. These brave riders were often beaten by angry mobs and arrested.

In Rock Hill, South Carolina, Lewis was attacked when he tried to enter a "whites-only" waiting room. Two weeks later, he joined another Freedom Ride going to Jackson, Mississippi. Near the end of his life, Lewis said, "We were determined not to let any act of violence keep us from our goal." He added, "We knew our lives could be threatened, but we had made up our minds not to turn back." Because of his Freedom Rider actions, Lewis was jailed for 40 days in the tough Mississippi State Penitentiary.

When the group CORE stopped the Freedom Rides due to violence, Lewis and fellow activist Diane Nash stepped up. They arranged for students from Nashville colleges to continue the rides. Their efforts helped bring the Freedom Rides to a successful end.

Leading SNCC

In 1963, Charles McDew stepped down as chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Lewis was chosen to take over. By this time, Lewis had already been arrested 24 times for his peaceful fight for equal rights. He served as SNCC chairman until 1966.

As SNCC chairman, Lewis was one of the "Big Six" leaders. These leaders organized the March on Washington that summer. Lewis was the youngest of the group. He was scheduled to speak just before Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Other leaders included Whitney Young, A. Philip Randolph, James Farmer, and Roy Wilkins.

In 1964, SNCC started Freedom Schools. They also launched the Mississippi Freedom Summer project. This project aimed to teach Black voters and help them register to vote. Lewis helped organize SNCC's work for Freedom Summer. He traveled the country, asking college students to spend their summer helping people vote in Mississippi. At that time, Mississippi had very few Black voters and strong resistance to the civil rights movement.

Selma to Montgomery Marches

In 1965, Lewis led the first of three Selma to Montgomery marches. On March 7, 1965, a day known as "Bloody Sunday," Lewis and activist Hosea Williams led over 600 marchers. They walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama.

At the end of the bridge, they were met by Alabama State Troopers. The troopers ordered them to leave. When the marchers stopped to pray, the police used tear gas. Mounted troopers then charged the peaceful demonstrators, beating them with nightsticks. Lewis's skull was fractured. He was helped to escape back across the bridge to Brown Chapel. This church in Selma was the movement's main meeting place. Lewis carried scars on his head from this attack for the rest of his life.

Working for Change (1966–1977)

In 1966, Lewis moved to New York City. He worked as an associate director for the Field Foundation. After about a year, he moved back to Atlanta. There, he directed the Community Organization Project for the Southern Regional Council (SRC). While at the SRC, he finished his degree from Fisk University.

In 1970, Lewis became the director of the Voter Education Project (VEP). He held this job until 1977. The VEP helped nearly four million minority voters register to vote under Lewis's leadership.

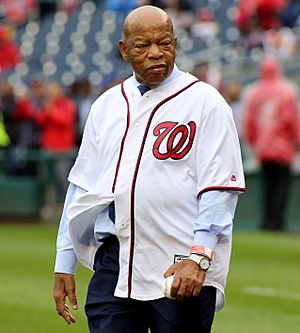

Political Career

Lewis was first elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1986. He served 17 terms, which is a very long time. The area he represented included most of Atlanta. Because he served for so long, he became the most senior member of the Georgia congressional delegation. Lewis was a leader in the Democratic Party in the House. He served as a chief deputy whip and later as a senior chief deputy whip.

Lewis often used his past experiences in the Civil Rights Movement in his political work. Every year, he made a trip to Alabama. He would retrace the route he marched in 1965 from Selma to Montgomery. Lewis worked to make this route part of the Historic National Trails program.

Committee Work

At the time of his death, Lewis served on the following important Congressional committee:

- Committee on Ways and Means

- He chaired the Subcommittee on Oversight. This group looked into how government money was spent.

Lewis was also a member of over 40 different groups within Congress, called caucuses. These groups focus on specific issues or interests.

National African American Museum

In 1988, Lewis introduced a bill to create a national African American museum in Washington, D.C. The bill did not pass at first. For 15 years, he kept introducing it with each new Congress. Each time, it was blocked in the Senate.

In 2003, the senator who often blocked it retired. The bill then gained support from both political parties. President George W. Bush signed the bill to create the museum. The National Museum of African American History and Culture opened on September 25, 2016. It is located next to the Washington Monument.

Books by and about John Lewis

Lewis's 1998 autobiography, Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement, won several awards. It was also a bestseller and was named a "Notable Book of the Year" by New York Times.

His life is also the subject of a 2002 book for young people, John Lewis: From Freedom Rider to Congressman. In 2012, Lewis released Across That Bridge.

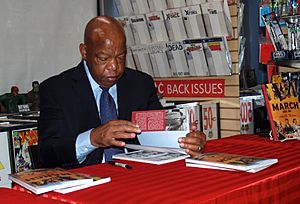

March Graphic Novel Series

In 2013, Lewis became the first member of Congress to write a graphic novel. It was a trilogy called March. This series tells the story of the Civil Rights Movement through Lewis's own eyes. The books are in black and white.

The first book, March: Book One, was published in August 2013. The second, March: Book Two, came out in January 2015. The final book, March: Book Three, was published in August 2016. Lewis wrote these books with Andrew Aydin. Nate Powell did the illustrations.

March: Book One won an "Author Honor" from the American Library Association's 2014 Coretta Scott King Book Awards. This award honors African American authors of children's books. Book One was also the first graphic novel to win a Robert F. Kennedy Book Award.

March: Book Two became a bestseller for graphic novels on both the New York Times and Washington Post lists.

When March: Book Three was released, all three books were in the top 3 spots on the New York Times bestseller list for graphic novels for six weeks in a row. The third book won many awards, including the 2017 Printz Award for young-adult literature and the 2016 National Book Award in Young People's Literature.

Run Graphic Novel Series

In 2018, Lewis and Andrew Aydin started another graphic novel series called Run. This series continues Lewis's story after the Civil Rights Act was passed. The first book was released on August 3, 2021, a year after Lewis passed away. It was one of his last projects.

Personal Life

John Lewis met Lillian Miles at a New Year's Eve party. They married in 1968. In 1976, they adopted a son named John-Miles Lewis. Lillian passed away on December 31, 2012.

Illness and Death

On December 29, 2019, Lewis announced he had been diagnosed with stage IV pancreatic cancer. He stayed in Washington D.C. for his treatment. Lewis said, "I have been in some kind of fight – for freedom, equality, basic human rights – for nearly my entire life. I have never faced a fight quite like the one I have now."

On July 17, 2020, John Lewis died at age 80 in Atlanta. He passed away on the same day as his friend and fellow civil rights activist C.T. Vivian. Lewis was the last surviving member of the "Big Six" civil rights leaders.

Then-President Donald Trump ordered all flags to be flown at half-staff to honor Lewis.

Interesting Facts About John Lewis

- As a boy, Lewis wanted to be a preacher. At age five, he would preach to his family's chickens on the farm.

- Lewis met Rosa Parks when he was 17 and Martin Luther King Jr. when he was 18.

- Lewis was the only living speaker from the March on Washington present when Barack Obama became president. Obama signed a photo for Lewis, writing, "Because of you, John. Barack Obama."

- After Obama was elected, Lewis said, "If you ask me whether the election ... is the fulfillment of Dr. King's dream, I say, 'No, it's just a down payment.'" He meant there was still more work to do for equality.

- After his death, Lewis became the first African-American lawmaker to lie in state in the United States Capitol Rotunda. This is a very high honor.

- In 2001, Lewis received the Profile in Courage Award for his amazing courage and leadership in civil rights.

John Lewis Quotes

- "When you see something that is not right, not fair, not just, you have to speak up. You have to say something; you have to do something."

- "Freedom is not a state; it is an act. It is not some enchanted garden perched high on a distant plateau where we can finally sit down and rest. Freedom is the continuous action we all must take, and each generation must do its part to create an even more fair, more just society."

- "I believe in nonviolence as a way of life, as a way of living."

- "We may not have chosen the time, but the time has chosen us."

- "Do not get lost in a sea of despair. Be hopeful, be optimistic. Our struggle is not the struggle of a day, a week, a month, or a year, it is the struggle of a lifetime. Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble."

Honors and Recognition

John Lewis received many honors for his work. In 1997, a sculpture called The Bridge was dedicated to him in Atlanta. In 1999, he received the Wallenberg Medal for his brave fight for human rights. He also received the Four Freedoms Award for Freedom of Speech.

Lewis was also given the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP. In 2004, he received the Golden Plate Award. In 2006, he won the U.S. Senator John Heinz Award for Public Service.

In 2010, Lewis received the first LBJ Liberty and Justice for All Award. The next year, President Barack Obama awarded Lewis the Presidential Medal of Freedom. This is one of the highest civilian honors in the United States.

In 2016, it was announced that a future United States Navy ship would be named USNS John Lewis. Also in 2016, Lewis received a Congressional Gold Medal for his role in the Selma to Montgomery marches. He also received the Liberty Medal. This award has been given to important international leaders like Malala Yousafzai.

After his death in 2020, many places were renamed in his honor. The Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, where "Bloody Sunday" happened, has had calls to be renamed for Lewis. Robert E. Lee High School in Virginia was renamed John R. Lewis High School. Troy University named its main building after him. Atlanta's Freedom Parkway was renamed John Lewis Freedom Parkway. Nashville's 5th Avenue was renamed John Lewis Way.

On February 21, 2021, President Joe Biden honored Lewis on his birthday. He urged Americans to "carry on his mission in the fight for justice and equality for all." In October 2021, the University of California, Santa Cruz named one of its colleges John R Lewis College.

Honorary Degrees

Lewis was awarded more than 50 honorary degrees from colleges and universities across the country. These degrees recognized his lifelong work for civil rights and justice.

See also

In Spanish: John Lewis (político) para niños

In Spanish: John Lewis (político) para niños

- John Lewis Voting Rights Act

- List of African-American United States representatives

- List of civil rights leaders

- List of United States Congress members who died in office

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |