Whitney Young facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Whitney Young

|

|

|---|---|

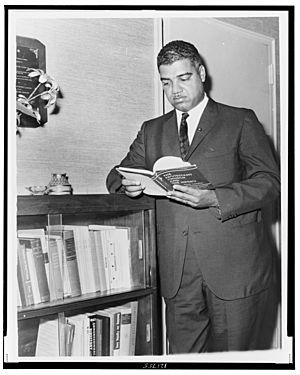

Young in 1964

|

|

| Born |

Whitney Moore Young Jr.

July 31, 1921 Shelby County, Kentucky, U.S.

|

| Died | March 11, 1971 (aged 49) Lagos, Nigeria

|

| Education | Kentucky State University (BS) Massachusetts Institute of Technology University of Minnesota, Twin Cities (MSW) |

| Organization | National Association for the Advancement of Colored People National Association of Social Workers National Urban League |

| Movement | American Civil Rights Movement |

| Awards | Rockefeller Foundation Grant Presidential Medal of Freedom |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1941–1946 |

| Rank | First Sergeant |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

Whitney Moore Young Jr. (July 31, 1921 – March 11, 1971) was an important American civil rights leader. He was trained as a social worker. Most of his career focused on ending unfair treatment in jobs. He also helped change the National Urban League. This group went from being quiet to actively fighting for equal chances for everyone. He wanted people who had been left out of opportunities to have the same chances as others.

Contents

Whitney Young's Early Life

Whitney Young was born in Shelby County, Kentucky, on July 31, 1921. His father, Whitney M. Young, Sr., was the president of the Lincoln Institute. His mother, Laura (Ray) Young, was a teacher. She was also the first female postmistress in Kentucky. President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed her to this job in 1940.

Young started at the Lincoln Institute when he was 13. He graduated as the top student in his class in 1937. His sister Margaret was the second-best student.

Young earned his college degree in social work from Kentucky State University. This was a college mainly for black students. Young hoped to become a medical doctor. He also played basketball for the university team. He was a member of the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity and its vice president. He became president of his senior class and graduated in 1941.

During World War II, Young learned electrical engineering. He trained at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Then, he joined a road construction team. This team had black soldiers and white officers from the South. After only three weeks, he was promoted from private to first sergeant. This caused some problems between the soldiers and officers. But Young was good at helping them understand each other. This experience made him want to work on race relations.

After the war, Young joined his wife, Margaret, at the University of Minnesota. He earned a master's degree in social work there in 1947. He also volunteered for the St. Paul branch of the National Urban League. In 1949, he became the industrial relations secretary for that branch.

In 1950, Young became the president of the National Urban League's Omaha, Nebraska chapter. In this role, he helped black workers get jobs that were only for white people before. Under his leadership, the chapter grew a lot. While in Omaha, Young also taught at the University of Nebraska from 1950 to 1954. He also taught at Creighton University from 1951 to 1952.

In 1954, he became the first dean of social work at Atlanta University. There, Young supported students who refused to attend a conference. This was because the conference did not hire enough African Americans. Young and his wife were also the first black members of the United Liberal Church. This church later became the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Atlanta. Young helped the church become more welcoming to everyone.

In 1957, he wrote a book called Some Pioneers in Social Work. In 1960, Young received a special grant from the Rockefeller Foundation. This allowed him to study at Harvard University. In the same year, he joined the NAACP. He became a state president and was a close friend of Roy Wilkins, the group's leader.

Leading the National Urban League

In 1961, when he was 40, Young became the executive director of the National Urban League. He was chosen by everyone on the board of directors. In just four years, he made the organization much bigger. It grew from 38 employees to 1,600. Its budget also grew from $325,000 to $6,100,000. Young led the Urban League until he passed away in 1971.

The Urban League used to be a careful and moderate group. Many of its members were white. During Young's ten years, he brought the group to the front of the American Civil Rights Movement. He greatly expanded what the group did. He also kept the support of important white business and political leaders.

Young said the Urban League's job was to help other groups. He saw them as "social engineers" and "planners." They worked with top leaders in business and government. As part of its new goals, Young started programs like "Street Academy." This program helped high school dropouts get ready for college. He also started "New Thrust" to help local black leaders solve community problems.

Young also asked the government for help for cities. He suggested a plan like the "Marshall Plan" for America. This plan asked for $145 billion to be spent over 10 years. Parts of this plan were used in President Lyndon B. Johnson's "War on Poverty." Young wrote about his ideas in two books. They were called To Be Equal (1964) and Beyond Racism (1969).

As the leader of the League, Young pushed big companies to hire more black people. He became good friends with company leaders like Henry Ford II. Some black people thought Young was too close to the white establishment. But Young said it was important to work within the system to make changes. He was still brave in fighting for civil rights. For example, in 1963, Young helped organize the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Many white business leaders were against it, but he still went forward.

Young did not want to be a politician himself. But he was an important advisor to Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon. In 1968, President-elect Richard Nixon's team asked Young to join his Cabinet. Young said no. He believed he could do more good through the Urban League.

Young had a very close relationship with President Johnson. In 1969, Johnson gave Young the Presidential Medal of Freedom. This is the highest award for a civilian. Young was impressed by Johnson's dedication to civil rights.

Making a Difference in Architecture

In 1968, Young gave a speech at the American Institute of Architects convention. He talked about how the group was quiet about problems in the country. He urged them to support the work of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr..

Because of Young's speech, the Institute made two important changes. They created a scholarship program for minority students who wanted to study architecture. This is called the AIA/Architects Foundation Diversity Advancement Scholarship. They also asked architects to get involved in social issues. To help with diversity, the AIA changed its rules. They banned unfair treatment based on sex, race, or religion. Later, they added other protections. The Institute also created the Whitney M. Young Jr. Award. This award honors people who show the same ideas of fairness and justice that Young fought for.

Also, "community design" became a new idea. This meant architects should work with people in cities on projects. The AIA started programs like the Regional/Urban Design Assistance Team Program. These programs help communities develop and include local people in the design process.

Leading Social Workers

Young was the President of the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) from 1969 to 1971. He took over when the group had money problems. Also, President Nixon's plans for the "War on Poverty" were unclear. In 1969, Young said that the country was in "deep trouble." He believed social work could help society survive and grow.

Young worked to make sure social workers kept up with the big challenges they faced. He asked social workers to help reduce poverty and bring people together. He also asked them to work to end the Vietnam War. In 1970, he challenged his group to lead the fight for social welfare. He said that leading in social welfare means taking action as professionals.

A tribute to Young in 1971 said he was always ready to fight for important issues. He did it with his usual calm and confidence. He was ready to work with powerful people to bring about change for those who had no power.

Young was also the Dean of the School of Social Work at Clark Atlanta University. This school is now named after him. In his last message as President for NASW, Young wrote that social workers should tell the public what they are doing and why.

His Final Years

On March 11, 1971, Young drowned while swimming in Lagos, Nigeria. He was there for a conference. President Nixon sent a plane to bring Young's body home. Nixon also went to Kentucky to speak at Young's funeral. Young was first buried in Lexington. But his wife later moved his body to Ferncliff Mausoleum in New York.

Family Life

In 1944, Whitney Young married Margaret Buckner Young. They had two daughters and moved to New Rochelle in 1961.

Their daughter, Marcia Young Cantarella, PhD, has worked as a dean at several colleges. She also wrote a book to help students finish college. His other daughter, Lauren Young Casteel, was the first black woman to lead a foundation in Colorado. Young also has several grandchildren and great-grandchildren. These include businessman Mark Boles and artist Jordan Casteel.

His Lasting Impact

In his speech at Young's funeral, President Nixon said Young's legacy was that "he knew how to accomplish what other people were merely for." Young's work was very important in breaking down barriers. These barriers were unfair rules and practices that held back African Americans.

Places and Awards Named After Him

Many places and awards are named after Whitney Young. In 1973, a bridge in Washington, D.C., was renamed the Whitney Young Memorial Bridge. Young's birthplace in Shelby County, Kentucky, is now a National Historic Landmark. It has a museum about his life.

In 1981, the United States Postal Service honored Young with a postage stamp. It was part of their Black Heritage series.

The Whitney Young School of Honors and Liberal Studies at Kentucky State University is named after him. Also, Clark Atlanta University named its School of Social Work after Young. This school is known for its "Afro-Centric" approach to social work.

The Boy Scouts of America created the Whitney M. Young Jr. Service Award. This award recognizes adults or groups who help create Scouting opportunities for young people from rural or low-income areas. The African American MBA Association at The Wharton School holds an annual Whitney M. Young Jr. Memorial Conference. It is the longest-running student conference at that school.

The America Center in Lagos, Nigeria, is also named after him.

Schools named after Young include Whitney M. Young Magnet High School in Chicago. There is also the Whitney M. Young Gifted & Talented Leadership Academy in Cleveland, Ohio. Other schools are in Fort Wayne, Indiana; Louisville, Kentucky; and Dallas, Texas.

The Whitney M. Young Health Center in Albany, New York, is also named after him.

The American Institute of Architects gives out the Whitney Young Jr. award every year. In 2019, Karen Braitmayer received this award. She was honored for her work in universal design.

About Whitney Young in Movies

A documentary film tells the story of Whitney Young. It is called The Powerbroker: Whitney Young's Fight for Civil Rights. The film shows how Young rose from a segregated Kentucky to become a national civil rights leader. It includes old videos, photos, and interviews. These interviews include Henry Louis Gates Jr., Ossie Davis, Julian Bond, Vernon Jordan, and Dorothy Height.