Roy Wilkins facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Roy Wilkins

|

|

|---|---|

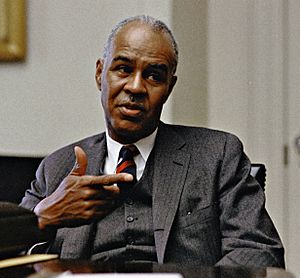

Wilkins at the White House on April 30, 1968.

|

|

| Executive Director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People | |

| In office 1955–1977 |

|

| Preceded by | Walter Francis White |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Hooks |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 31, 1901 St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | September 8, 1981 (aged 80) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Minnie Badeau

(m. 1929) |

| Education | University of Minnesota (BA) |

| Awards | Spingarn Medal |

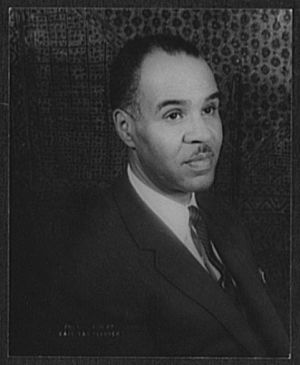

Roy Ottoway Wilkins (born August 30, 1901 – died September 8, 1981) was a very important leader in the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. This movement worked for equal rights for all people, especially African Americans. Roy Wilkins was active from the 1930s to the 1970s.

His most famous job was leading the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). He was the Executive Secretary from 1955 to 1963 and then the Executive Director from 1964 to 1977. Wilkins played a key role in many big marches for civil rights. He also helped African-American writers and used his voice to fight for equality. Roy Wilkins also supported military members and veterans, recognizing their service.

Contents

Roy Wilkins' Early Life

Roy Wilkins was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on August 30, 1901. His father had to leave town because he was in danger after standing up to a white man. When Roy was four, his mother passed away from tuberculosis. Roy and his siblings were then raised by their aunt and uncle. They lived in the Rondo Neighborhood of St. Paul, Minnesota. Roy went to local schools there.

In 1923, he graduated from the University of Minnesota. He earned a degree in sociology, which is the study of how people live in groups. In 1929, he married Aminda "Minnie" Badeau, who was a social worker. They did not have their own children, but they raised two children from Roy's relative, Hazel Wilkins-Colton.

Roy Wilkins' Early Career

While in college, Roy Wilkins worked as a journalist for The Minnesota Daily. He also became the editor of The Appeal, an African-American newspaper. After graduating in 1923, he became the editor of The Call newspaper.

His work against the Jim Crow Laws led him to become an activist. These laws enforced racial segregation in the Southern United States. In 1931, he moved to New York City. He became an assistant secretary for the NAACP, working under Walter Francis White. When W. E. B. Du Bois left the NAACP in 1934, Wilkins took over as editor of The Crisis. This was the official magazine of the NAACP.

From 1949 to 1950, Wilkins led the National Emergency Civil Rights Mobilization. This group included over 100 local and national organizations. He also advised the War Department during World War II.

In 1950, Wilkins helped create the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights (LCCR). He worked with A. Philip Randolph and Arnold Aronson. The LCCR became a very important civil rights group. It has helped pass every major civil rights law since 1957.

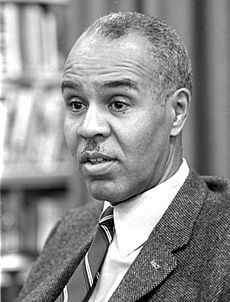

Leading the NAACP

In 1955, Roy Wilkins was chosen to be the executive secretary of the NAACP. In 1964, he became its executive director. He was known as an excellent speaker for the Civil Rights Movement. One of his first actions was to help civil rights activists in Mississippi. These activists were being financially pressured by members of the White Citizens Councils.

Wilkins supported a plan by Dr. T. R. M. Howard. This plan suggested that Black businesses and groups move their money to the Black-owned Tri-State Bank of Memphis, Tennessee. By the end of 1955, about $300,000 was deposited there. This money allowed Tri-State to give loans to Black people who were denied loans by white banks.

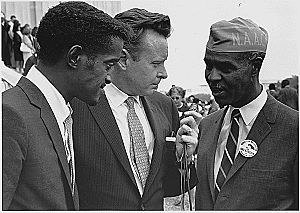

Wilkins helped organize and participated in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August 1963. He strongly believed in protesting peacefully. He also took part in the Selma to Montgomery marches (1965) and the March Against Fear (1966).

He believed that laws were the best way to achieve change. He spoke at many hearings in the United States Congress. He also met with Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and Jimmy Carter. These achievements earned him respect and the nickname "Mr. Civil Rights."

Wilkins did not support the "black power" movement. He thought it was too aggressive and went against his belief in nonviolence. He was against racism in all forms. He also stated that violence and separating Black and white people were not the answer. In 1962, he criticized the direct action of the Freedom Riders. However, after the Birmingham campaign, he changed his mind. He was arrested for leading a protest in 1963.

Wilkins believed in slowly integrating society, rather than making sudden, radical changes. In a 1964 interview, he said that Black people wanted better public schools. This included ending segregation and having the same quality education for all children. He believed that destroying the public school system was very dangerous.

However, his moderate views sometimes caused disagreements. Younger, more active Black leaders saw him as too cautious. Wilkins was also a member of Omega Psi Phi. This was a fraternity for African Americans that focused on civil rights.

In 1964, the NAACP gave him the Spingarn Medal. During his time as leader, the NAACP was very important in the Civil Rights Movement. They helped achieve major victories like Brown v. Board of Education, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In 1968, Wilkins led the U.S. group at the International Conference on Human Rights. He retired from the NAACP in 1977 at age 76. Benjamin Hooks took over his role. Wilkins was given the title Director Emeritus of the NAACP that same year.

Roy Wilkins' Views

Wilkins was a strong liberal. He supported American values during the Cold War. He spoke out against suspected and actual communists within the Civil Rights Movement. Some people on the left side of the movement criticized him. They felt he was too cautious and too willing to work with white anti-communists.

In 1951, the FBI and the US State Department worked with the NAACP and Wilkins. They arranged for a leaflet to be printed and given out in Africa. This leaflet was meant to spread negative views about the Black political activist and entertainer Paul Robeson.

When Robeson was misquoted saying that Black people would not support the U.S. in a war against the Soviet Union, Wilkins disagreed. Wilkins stated that Black Americans would always serve in the armed forces, no matter what. In 1952, Wilkins even threatened to close an NAACP youth group if they did not cancel a concert featuring Robeson.

Supporting the Military

During the presidencies of Kennedy and Johnson, the Civil Rights Movement was at its strongest. Many civil rights groups focused on issues within the United States. However, Wilkins also focused on international matters. His friendship with President Johnson gave him a platform to speak about war efforts and civil rights policies.

His views on Black military members serving in the U.S. military were different from some other civil rights leaders. While many groups spoke out against the Vietnam War, Wilkins focused on what African Americans could gain from serving. He highlighted the financial benefits of military service. He also stressed the importance of African-American citizens taking part in the first integrated American army.

In 1969, Lyndon Johnson gave him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. This award recognized Wilkins' efforts to promote equality in international affairs.

Legacy of Roy Wilkins

Roy Wilkins passed away on September 8, 1981, in New York City. He was 80 years old. In his later life, he was often called the "Senior Statesman" of the Civil Rights Movement.

In 1982, his autobiography, Standing Fast: The Autobiography of Roy Wilkins, was published after his death.

The Roy Wilkins Renown Service Award was created in 1980. It honors members of the Armed Forces who show a spirit of equality and human rights. The St. Paul Auditorium was renamed for Wilkins in 1985. The Roy Wilkins Center for Human Relations and Social Justice was started at the University of Minnesota in 1992. Roy Wilkins Park in St. Albans, Queens, New York, is also named after him.

In 2001, the U.S. Postal Service released a stamp honoring Wilkins. In 2002, Molefi Kete Asante included Roy Wilkins on his list of the 100 Greatest African Americans.

He is played by actor Joe Morton in the 2016 TV drama All the Way.

See also

- Civil rights movement (1896–1954)

- Leadership Conference on Civil Rights

- List of civil rights leaders

- Roger Wilkins, Roy's nephew, also a civil rights activist

- Roy Wilkins Auditorium, an arena in Saint Paul, Minnesota

- Timeline of the civil rights movement

- Thurgood Marshall, Wilkins' colleague at the NAACP and U.S. Supreme Court Justice

- March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |